Ethics & Policy

We Already Have an Ethics Framework for AI (opinion)

For the third time in my career as an academic librarian, we are facing a digital revolution that is radically and rapidly transforming our information ecosystem. The first was when the internet became broadly available by virtue of browsers. The second was the emergence of Web 2.0 with mobile and social media. The third—and current—results from the increasing ubiquity of AI, especially generative AI.

Once again, I am hearing a combination of fear-based thinking alongside a rhetoric of inevitability and scoldings directed at those critics who are portrayed as “resistant to change” by AI proponents. I wish I were hearing more voices advocating for the benefits of specific uses of AI alongside clearheaded acknowledgment of risks of AI in specific circumstances and an emphasis on risk mitigation. Academics should approach AI as a tool for specific interventions and then assess the ethics of those interventions.

Caution is warranted. The burden of building trust should be on the AI developers and corporations. While Web 2.0 delivered on its promise of a more interactive, collaborative experience on the web that centered user-generated content, the fulfillment of that promise was not without societal costs.

In retrospect, Web 2.0 arguably fails to meet the basic standard of beneficence. It is implicated in the global rise of authoritarianism, in the undermining of truth as a value, in promoting both polarization and extremism, in degrading the quality of our attention and thinking, in a growing and serious mental health crisis, and in the spread of an epidemic of loneliness. The information technology sector has earned our deep skepticism. We should do everything in our power to learn from the mistakes of our past and do what we can to prevent similar outcomes in the future.

We need to develop an ethical framework for assessing uses of new information technology—and specifically AI—that can guide individuals and institutions as they consider employing, promoting and licensing these tools for various functions. There are two main factors about AI that complicate ethical analysis. The first is that an interaction with AI frequently continues past the initial user-AI transaction; information from that transaction can become part of the system’s training set. Secondly, there is often a significant lack of transparency about what the AI model is doing under the surface, making it difficult to assess. We should demand as much transparency as possible from tool providers.

Academia already has an agreed-upon set of ethical principles and processes for assessing potential interventions. The principles in “The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research” govern our approach to research with humans and can fruitfully be applied if we think of potential uses of AI as interventions. These principles not only benefit academia in making assessments about using AI but also provide a framework for technology developers thinking through their design requirements.

The Belmont Report articulates three primary ethical principles:

- Respect for persons

- Beneficence

- Justice

“Respect for persons,” as it’s been translated into U.S. code and practiced by IRBs, has several facets, including autonomy, informed consent and privacy. Autonomy means that individuals should have the power to control their engagement and should not be coerced to engage. Informed consent requires that people should have clear information so that they understand what they are consenting to. Privacy means a person should have control and choice about how their personal information is collected, stored, used and shared.

Following are some questions we might ask to assess whether a particular AI intervention honors autonomy.

- Is it obvious to users that they are interacting with AI? This becomes increasingly important as AI is integrated into other tools.

- Is it obvious when something was generated by AI?

- Can users control how their information is harvested by AI, or is the only option to not use the tool?

- Can users access essential services without engaging with AI? If not, that may be coercive.

- Can users control how information they produce is used by AI? This includes whether their content is used to train AI models.

- Is there a risk of overreliance, especially if there are design elements that encourage psychological dependency? From an educational perspective, is using an AI tool for a particular purpose likely to prevent users from learning foundational skills so that they become dependent on the model?

In relation to informed consent, is the information provided about what the model is doing both sufficient and in a form that a person who is neither a lawyer nor a technology developer can understand? It is imperative that users be given information about what data is going to be collected from which sources and what will happen to that data.

Privacy infringement happens either when someone’s personal data is revealed or used in an unintended way or when information thought private is correctly inferred. When there is sufficient data and computing power, re-identification of research subjects is a danger. Given that “de-identification of data” is one of the most common strategies for risk mitigation in human subjects’ research, and there is an increasing emphasis on publishing data sets for the purposes of research reproducibility, this is an area of ethical concern that demands attention. Privacy emphasizes that individuals should have control over their private information, but how that private information is used should also be assessed in relation to the second major principle—beneficence.

Beneficence is the general principle that says that the benefits should outweigh the risks of harm and that risks should be mitigated as much as possible. Beneficence should be assessed on multiple levels—both the individual and the systemic. The principle of beneficence demands that we pay particularly careful attention to those who are vulnerable because they lack full autonomy, such as minors.

Even when making personal decisions, we need to think about potential systemic harms. For example, some vendors offer tools that allow researchers to share their personal information in order to generate highly personalized search results—increasing research efficiency. As the tool builds a picture of the researcher, it will presumably continue to refine results with the goal of not showing things that it does not believe are useful to the researcher. This may benefit the individual researcher. However, on a systemic level, if such practices become ubiquitous, will the boundaries between various discourses harden? Will researchers doing similar scholarship get shown an increasingly narrow view of the world, focused on research and outlooks that are similar to each other, while researchers in a different discourse are shown a separate view of the world? If so, would this disempower interdisciplinary or radically novel research or exacerbate disciplinary confirmation bias? Can such risks be mitigated? We need to develop a habit of thinking about potential impacts beyond the individual in order to create mitigations.

There are many potential benefits to certain uses of AI. There are real possibilities it can rapidly advance medicine and science—see, for example, the stunning successes of the protein structure database AlphaFold. There are corresponding potentialities for swift advances in technology that can serve the common good, including in our fight against the climate crisis. The potential benefits are transformative, and a good ethical framework should encourage them. The principle of beneficence does not demand that there are no risks, but that we should identify uses where the benefits are significant and that we mitigate the risks, both individual and systemic. Risks can be minimized by improving the tools, such as work to prevent them from hallucinating, propagating toxic or misleading content, or delivering inappropriate advice.

Questions of beneficence also require attention to environmental impacts of generative AI models. Because the models require vast amounts of computing power and, therefore, electricity, using them taxes our collective infrastructure and contributes to pollution. When analyzing a particular use through the ethical lens of beneficence, we should ask whether the proposed use provides enough likely benefit to justify the environmental harm. Use of AI for trivial purposes arguably fails the test for beneficence.

The principle of justice demands that the people and populations who bear the risks should also receive the benefits. With AI, there are significant equity concerns. For example, generative AI may be trained on data that includes our biases, both current and historic. Models must be rigorously tested to see if they create prejudicial or misleading content. Similarly, AI tools should be closely interrogated to ensure that they do not work better for some groups than for others. Inequities impact the calculations of beneficence and, depending on the stakes of the use case, could make the use unethical.

Another consideration in relation to the principle of justice and AI is the issue of fair compensation and attribution. It is important that AI does not undermine creative economies. Additionally, scholars are important content producers, and the academic coin of the realm is citations. Content creators have a right to expect that their work will be used with integrity, will be cited and that they will be remunerated appropriately. As part of autonomy, content creators should also be able to control whether their material is used in a training set, and this should, at least going forward, be part of author negotiations. Similarly, the use of AI tools in research should be cited in the scholarly product; we need to develop standards about what is appropriate to include in methodology sections and citations, and possibly when an AI model should be granted co-authorial status.

The principles outlined above from the Belmont Report are, I believe, sufficiently flexible to allow for further and rapid developments in the field. Academia has a long history of using them as guidance to make ethical assessments. They give us a shared foundation from which we can ethically promote the use of AI to be of benefit to the world while simultaneously avoiding the types of harms that can poison the promise.

Ethics & Policy

5 interesting stats to start your week

Third of UK marketers have ‘dramatically’ changed AI approach since AI Act

More than a third (37%) of UK marketers say they have ‘dramatically’ changed their approach to AI, since the introduction of the European Union’s AI Act a year ago, according to research by SAP Emarsys.

Additionally, nearly half (44%) of UK marketers say their approach to AI is more ethical than it was this time last year, while 46% report a better understanding of AI ethics, and 48% claim full compliance with the AI Act, which is designed to ensure safe and transparent AI.

The act sets out a phased approach to regulating the technology, classifying models into risk categories and setting up legal, technological, and governance frameworks which will come into place over the next two years.

However, some marketers are sceptical about the legislation, with 28% raising concerns that the AI Act will lead to the end of innovation in marketing.

Source: SAP Emarsys

Shoppers more likely to trust user reviews than influencers

Nearly two-thirds (65%) of UK consumers say they have made a purchase based on online reviews or comments from fellow shoppers, as opposed to 58% who say they have made a purchase thanks to a social media endorsement.

Nearly two-thirds (65%) of UK consumers say they have made a purchase based on online reviews or comments from fellow shoppers, as opposed to 58% who say they have made a purchase thanks to a social media endorsement.

Sports and leisure equipment (63%), decorative homewares (58%), luxury goods (56%), and cultural events (55%) are identified as product categories where consumers are most likely to find peer-to-peer information valuable.

Accurate product information was found to be a key factor in whether a review was positive or negative. Two-thirds (66%) of UK shoppers say that discrepancies between the product they receive and its description are a key reason for leaving negative reviews, whereas 40% of respondents say they have returned an item in the past year because the product details were inaccurate or misleading.

According to research by Akeeno, purchases driven by influencer activity have also declined since 2023, with 50% reporting having made a purchase based on influencer content in 2025 compared to 54% two years ago.

Source: Akeeno

77% of B2B marketing leaders say buyers still rely on their networks

When vetting what brands to work with, 77% of B2B marketing leaders say potential buyers still look at the company’s wider network as well as its own channels.

When vetting what brands to work with, 77% of B2B marketing leaders say potential buyers still look at the company’s wider network as well as its own channels.

Given the amount of content professionals are faced with, they are more likely to rely on other professionals they already know and trust, according to research from LinkedIn.

More than two-fifths (43%) of B2B marketers globally say their network is still their primary source for advice at work, ahead of family and friends, search engines, and AI tools.

Additionally, younger professionals surveyed say they are still somewhat sceptical of AI, with three-quarters (75%) of 18- to 24-year-olds saying that even as AI becomes more advanced, there’s still no substitute for the intuition and insights they get from trusted colleagues.

Since professionals are more likely to trust content and advice from peers, marketers are now investing more in creators, employees, and subject matter experts to build trust. As a result, 80% of marketers say trusted creators are now essential to earning credibility with younger buyers.

Source: LinkedIn

Business confidence up 11 points but leaders remain concerned about economy

Business leader confidence has increased slightly from last month, having risen from -72 in July to -61 in August.

Business leader confidence has increased slightly from last month, having risen from -72 in July to -61 in August.

The IoD Directors’ Economic Confidence Index, which measures business leader optimism in prospects for the UK economy, is now back to where it was immediately after last year’s Budget.

This improvement comes from several factors, including the rise in investment intentions (up from -27 in July to -8 in August), the rise in headcount expectations from -23 to -4 over the same period, and the increase in revenue expectations from -8 to 12.

Additionally, business leaders’ confidence in their own organisations is also up, standing at 1 in August compared to -9 in July.

Several factors were identified as being of concern for business leaders; these include UK economic conditions at 76%, up from 67% in May, and both employment taxes (remaining at 59%) and business taxes (up to 47%, from 45%) continuing to be of significant concern.

Source: The Institute of Directors

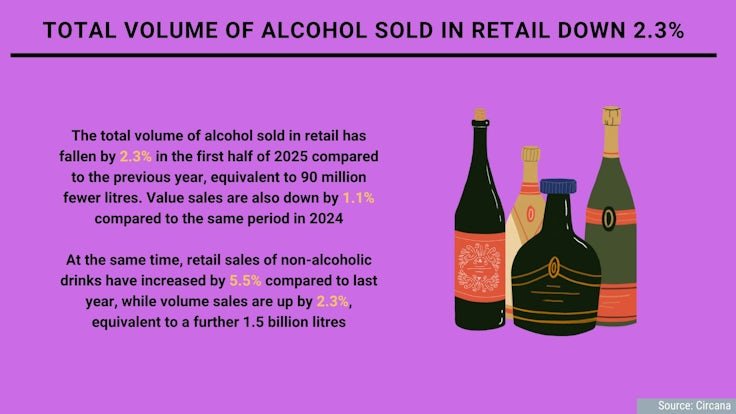

Total volume of alcohol sold in retail down 2.3%

The total volume of alcohol sold in retail has fallen by 2.3% in the first half of 2025 compared to the previous year, equivalent to 90 million fewer litres. Value sales are also down by 1.1% compared to the same period in 2024.

The total volume of alcohol sold in retail has fallen by 2.3% in the first half of 2025 compared to the previous year, equivalent to 90 million fewer litres. Value sales are also down by 1.1% compared to the same period in 2024.

At the same time, retail sales of non-alcoholic drinks have increased by 5.5% compared to last year, while volume sales are up by 2.3%, equivalent to a further 1.5 billion litres.

As the demand for non-alcoholic beverages grows, people increasingly expect these options to be available in their local bars and restaurants, with 55% of Brits and Europeans now expecting bars to always serve non-alcoholic beer.

As well as this, there are shifts happening within the alcoholic beverages category with value sales of no and low-alcohol spirits rising by 16.1%, and sales of ready-to-drink spirits growing by 11.6% compared to last year.

Source: Circana

Ethics & Policy

AI ethics under scrutiny, young people most exposed

New reports into the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) showed incidents linked to ethical breaches have more than doubled in just two years.

At the same time, entry-level job opportunities have been shrinking, partly due to the spread of this automation.

AI is moving from the margins to the mainstream at extraordinary speed and both workplaces and universities are struggling to keep up.

Tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini and Claude are now being used to draft emails, analyse data, write code, mark essays and even decide who gets a job interview.

Alongside this rapid rollout, a March report from McKinsey, one by the OECD in July and an earlier Rand report warned of a sharp increase in ethical controversies — from cheating scandals in exams to biased recruitment systems and cybersecurity threats — leaving regulators and institutions scrambling to respond.

The McKinsey survey said almost eight in 10 organisations now used AI in at least one business function, up from half in 2022.

While adoption promises faster workflows and lower costs, many companies deploy AI without clear policies. Universities face similar struggles, with students increasingly relying on AI for assignments and exams while academic rules remain inconsistent, it said.

The OECD’s AI Incidents and Hazards Monitor reported that ethical and operational issues involving AI have more than doubled since 2022.

Common concerns included accountability — who is responsible when AI errs; transparency — whether users understand AI decisions; and fairness, whether AI discriminates against certain groups.

Many models operated as “black boxes”, producing results without explanation, making errors hard to detect and correct, it said.

In workplaces, AI is used to screen CVs, rank applicants, and monitor performance. Yet studies show AI trained on historical data can replicate biases, unintentionally favouring certain groups.

Rand reported that AI was also used to manipulate information, influence decisions in sensitive sectors, and conduct cyberattacks.

Meanwhile, 41 per cent of professionals report that AI-driven change is harming their mental health, with younger workers feeling most anxious about job security.

LinkedIn data showed that entry-level roles in the US have fallen by more than 35 per cent since 2023, while 63 per cent of executives expected AI to replace tasks currently done by junior staff.

Aneesh Raman, LinkedIn’s chief economic opportunity officer, described this as “a perfect storm” for new graduates: Hiring freezes, economic uncertainty and AI disruption, as the BBC reported August 26.

LinkedIn forecasts that 70 per cent of jobs will look very different by 2030.

Recent Stanford research confirmed that employment among early-career workers in AI-exposed roles has dropped 13 per cent since generative AI became widespread, while more experienced workers or less AI-exposed roles remained stable.

Companies are adjusting through layoffs rather than pay cuts, squeezing younger workers out, it found.

In Belgium, AI ethics and fairness debates have intensified following a scandal in Flanders’ medical entrance exams.

Investigators caught three candidates using ChatGPT during the test.

Separately, 19 students filed appeals, suspecting others may have used AI unfairly after unusually high pass rates: Some 2,608 of 5,544 participants passed but only 1,741 could enter medical school. The success rate jumped to 47 per cent from 18.9 per cent in 2024, raising concerns about fairness and potential AI misuse.

Flemish education minister Zuhal Demir condemned the incidents, saying students who used AI had “cheated themselves, the university and society”.

Exam commission chair Professor Jan Eggermont noted that the higher pass rate might also reflect easier questions, which were deliberately simplified after the previous year’s exam proved excessively difficult, as well as the record number of participants, rather than AI-assisted cheating alone.

French-speaking universities, in the other part of the country, were not concerned by this scandal, as they still conduct medical entrance exams entirely on paper, something Demir said he was considering going back to.

Ethics & Policy

Governing AI with inclusion: An Egyptian model for the Global South

When artificial intelligence tools began spreading beyond technical circles and into the hands of everyday users, I saw a real opportunity to understand this profound transformation and harness AI’s potential to benefit Egypt as a state and its citizens. I also had questions: Is AI truly a national priority for Egypt? Do we need a legal framework to regulate it? Does it provide adequate protection for citizens? And is it safe enough for vulnerable groups like women and children?

These questions were not rhetorical. They were the drivers behind my decision to work on a legislative proposal for AI governance. My goal was to craft a national framework rooted in inclusion, dialogue, and development, one that does not simply follow global trends but actively shapes them to serve our society’s interests. The journey Egypt undertook can offer inspiration for other countries navigating the path toward fair and inclusive digital policies.

Egypt’s AI Development Journey

Over the past five years, Egypt has accelerated its commitment to AI as a pillar of its Egypt Vision 2030 for sustainable development. In May 2021, the government launched its first National AI Strategy, focusing on capacity building, integrating AI in the public sector, and fostering international collaboration. A National AI Council was established under the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (MCIT) to oversee implementation. In January 2025, President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi unveiled the second National AI Strategy (2025–2030), which is built around six pillars: governance, technology, data, infrastructure, ecosystem development, and capacity building.

Since then, the MCIT has launched several initiatives, including training 100,000 young people through the “Our Future is Digital” programme, partnering with UNESCO to assess AI readiness, and integrating AI into health, education, and infrastructure projects. Today, Egypt hosts AI research centres, university departments, and partnerships with global tech companies—positioning itself as a regional innovation hub.

AI-led education reform

AI is not reserved for startups and hospitals. In May 2025, President El-Sisi instructed the government to consider introducing AI as a compulsory subject in pre-university education. In April 2025, I formally submitted a parliamentary request and another to the Deputy Prime Minister, suggesting that the government include AI education as part of a broader vision to prepare future generations, as outlined in Egypt’s initial AI strategy. The political leadership’s support for this proposal highlighted the value of synergy between decision-makers and civil society. The Ministries of Education and Communications are now exploring how to integrate AI concepts, ethics, and basic programming into school curricula.

From dialogue to legislation: My journey in AI policymaking

As Deputy Chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee in Parliament, I believe AI policymaking should not be confined to closed-door discussions. It must include all voices. In shaping Egypt’s AI policy, we brought together:

- The private sector, from startups to multinationals, will contribute its views on regulations, data protection, and innovation.

- Civil society – to emphasise ethical AI, algorithmic justice, and protection of vulnerable groups.

- International organisations, such as the OECD, UNDP, and UNESCO, share global best practices and experiences.

- Academic institutions – I co-hosted policy dialogues with the American University in Cairo and the American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) to discuss governance standards and capacity development.

From recommendations to action: The government listening session

To transform dialogue into real policy, I formally requested the MCIT to host a listening session focused solely on the private sector. Over 70 companies and experts attended, sharing their recommendations directly with government officials.

This marked a key turning point, transitioning the initiative from a parliamentary effort into a participatory, cross-sectoral collaboration.

Drafting the law: Objectives, transparency, and risk-based classification

Based on these consultations, participants developed a legislative proposal grounded in transparency, fairness, and inclusivity. The proposed law includes the following core objectives:

- Support education and scientific research in the field of artificial intelligence

- Provide specific protection for individuals and groups most vulnerable to the potential risks of AI technologies

- Govern AI systems in alignment with Egypt’s international commitments and national legal framework

- Enhance Egypt’s position as a regional and international hub for AI innovation, in partnership with development institutions

- Support and encourage private sector investment in the field of AI, especially for startups and small enterprises

- Promote Egypt’s transition to a digital economy powered by advanced technologies and AI

To operationalise these objectives, the bill includes:

- Clear definitions of AI systems

- Data protection measures aligned with Egypt’s 2020 Personal Data Protection Law

- Mandatory algorithmic fairness, transparency, and auditability

- Incentives for innovation, such as AI incubators and R&D centres

Establishment of ethics committees and training programmes for public sector staff

The draft law also introduces a risk-based classification framework, aligning it with global best practices, which categorises AI systems into three tiers:

1. Prohibited AI systems – These are banned outright due to unacceptable risks, including harm to safety, rights, or public order.

2. High-risk AI systems – These require prior approval, detailed documentation, transparency, and ongoing regulatory oversight. Common examples include AI used in healthcare, law enforcement, critical infrastructure, and education.

3. Limited-risk AI systems – These are permitted with minimal safeguards, such as user transparency, labelling of AI-generated content, and optional user consent. Examples include recommendation engines and chatbots.

This classification system ensures proportionality in regulation, protecting the public interest without stifling innovation.

Global recognition: The IPU applauds Egypt’s model

The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), representing over 179 national parliaments, praised Egypt’s AI bill as a model for inclusive AI governance. It highlighted that involving all stakeholders builds public trust in digital policy and reinforces the legitimacy of technology laws.

Key lessons learned

- Inclusion builds trust – Multistakeholder participation leads to more practical and sustainable policies.

- Political will matters – President El-Sisi’s support elevated AI from a tech topic to a national priority.

- Laws evolve through experience – Our draft legislation is designed to be updated as the field develops.

- Education is the ultimate infrastructure – Bridging the future digital divide begins in the classroom.

- Ethics come first – From the outset, we established values that focus on fairness, transparency, and non-discrimination.

Challenges ahead

As the draft bill progresses into final legislation and implementation, several challenges lie ahead:

- Training regulators on AI fundamentals

- Equipping public institutions to adopt ethical AI

- Reducing the urban-rural digital divide

- Ensuring national sovereignty over data

- Enhancing Egypt’s global role as a policymaker—not just a policy recipient

Ensuring representation in AI policy

As a female legislator leading this effort, it was important for me to prioritise the representation of women, youth, and marginalised groups in technology policymaking. If AI is built on biased data, it reproduces those biases. That’s why the policymaking table must be round, diverse, and representative.

A vision for the region

I look forward to seeing Egypt:

- Advance regional AI policy partnerships across the Middle East and Africa

- Embedd AI ethics in all levels of education

- Invest in AI for the public good

Because AI should serve people—not control them.

Better laws for a better future

This journey taught me that governing AI requires courage to legislate before all the answers are known—and humility to listen to every voice. Egypt’s experience isn’t just about technology; it’s about building trust and shared ownership. And perhaps that’s the most important infrastructure of all.

The post Governing AI with inclusion: An Egyptian model for the Global South appeared first on OECD.AI.

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences3 months ago

Events & Conferences3 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months ago

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months agoDonald Trump suggests US government review subsidies to Elon Musk’s companies

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi