Education

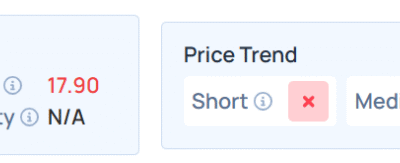

VEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

VEX Robotics launched VEX AIR, an AI-powered robotics system for classrooms, and VEX AIM, an upcoming platform designed to make machine learning approachable and fun for students of all ages.

Notably, VEX Aim was recently showcased at the White House’s first AI Edu Task Force meeting, demonstrating meaningful, hands-on experiences with AI that go beyond theory and into real-world applications.

By the time they reach high school, most students have already decided whether or not they think science and math are ‘cool’. That’s where VEX comes in.

Education

Meet the three-year-olds helping anxious teens spend more time in school

BBC

BBCSiena never thought she’d be taking lessons in communication and confidence from a three-year-old.

She is part of a scheme that pairs teenagers with toddlers from a local nursery in a bid to help increase school attendance and engagement.

The 13-year-old says she had a “lot of anxiety” so would never be in school, but “coming here has taught me more about how to communicate and be more confident and it’s funny a toddler is teaching us things.”

While she didn’t think the project would help increase her attendance, it has actually more than doubled.

“It’s really helped me,” she says. “The toddler I’m paired with has grown so much and it makes me so happy to see,” she tells the BBC’s Morning Live.

Morning Live returns on Monday at 0930am. Watch this and more here.

As the summer holiday ends and the new school year begins, many parents will be worrying about their child’s attendance and engagement.

The issue of school avoidance is a big one and one charity has created this mentoring programme with its research suggesting that a disengaged teenager having responsibility for a younger child in a controlled setting can have a positive impact on their engagement with school and learning.

Since the pandemic, school absence has almost doubled – in the 2024/25 academic year, 17.79% of pupils were persistently absent meaning they missed 10% or more school sessions.

Data shows that just 10 days of absence can halve the chance of a student getting at least a grade 5 in English and Maths.

Miller, 12, another pupil participating in the scheme says he struggles to stay in class because he has a lot of energy, but that the sessions have helped him focus more on his school work.

“I was a bit nervous and it took me two weeks to say yes to the project as I was really shy.”

Miller has been paired with three-year-old Andrew and says they are now really close.

“When he sees me he runs up to me and gives me a hug.”

As well as developing his confidence, Miller adds that the sessions have made him feel calmer and less energetic.

Sam Marcus is the director of services at Power2, the charity that runs this scheme, currently only in London and Manchester.

It offers various mentoring programmes to children of all ages and over the years has helped 27,000 children and young people to re-engage with school.

This particular project works across a 16-week period where teenagers visit a local nursery once a week and mentor a child.

The pairing is well thought out – “it’s often based on personalities so a really vibrant toddler might be paired with a shy teenager or a timid toddler is matched with a boisterous teen which helps create a much softer side to them.”

The aim is that the bond between the toddler and teen will help build confidence and accountability that encourages them to then turn up to lessons and “a sense of responsibility to young people who often aren’t given those positions”.

“If a child is disruptive in class, they often aren’t given those opportunities to prove themselves to be more than that,” she says.

“We help the teen become a positive role model for that child,” she adds. The teenagers also have reflective sessions after the nursery visit to learn more about building healthy relationships and positive attitudes.

According to Power2, 78% young people on the scheme improve their attitude to learning and 83% of them have improved self esteem.

Often the toddler also has additional needs such as speech and language delays or difficulty making friends and Lisa, who teaches at one of the nursery’s involved in the project says it has a big impact on the children.

“They love having that special person each Friday,” she says. “It’s lovely to see them having that one to one time and the kids running up hugging the teens every week.”

How can you help your child with attendance?

This scheme is one small programme aiming to help with the very complex issue of school advoidance.

The Department for Education provides guidance on what to do if your child is struggling to attend school.

Dr Weisberg, a consultant clinical psychologist who works with young people who feel disconnected from their education, says often children find it hard to engage with education because “there are lots of rules at school and none of them are under the kid’s control”.

In contrast, this programme “gives them a responsibility and empowerment to learn from what works and what doesn’t and they feel like they are making a real difference”.

He gives three tips on how parents can work with their child to improve their attendance:

- Raise it with the school – “Make sure the school are on the same page and there are lots of charities and support available to make things better.”

- Give the child agency – “Be available. I recommend parents spend at least 10 minutes a day with each child without distractions like screens or phones.”

- Follow their lead – With younger children, it’s important for parents to play with them and follow their lead which can “foster healthy relationships and confidence”.

Sue Armstrong, a clinical service manager at relationship support charity Relate, says other ways to support your child through school anxiety and avoidance include:

- Avoid blaming yourself and your child – “It’s important to try not to feel guilty or that this is somehow your fault”.

- Look forward to positive things – “Continuing ‘normal’ family events will help all of you. Finding time, when you can, for your own interests, as a couple and individually, is vital”.

- Accept there will be ups and downs – “You may feel you’re being pulled in every direction, having to keep a job going and support your child when they may be feeling very anxious and confused, that there’s no space left for you”.

Education

AI Has Broken High School and College

This is Atlantic Intelligence, a newsletter in which our writers help you wrap your mind around artificial intelligence and a new machine age. Sign up here.

Another school year is beginning—which means another year of AI-written essays, AI-completed problem sets, and, for teachers, AI-generated curricula. For the first time, seniors in high school have had their entire high-school careers defined to some extent by chatbots. The same applies for seniors in college: ChatGPT released in November 2022, meaning unlike last year’s graduating class, this year’s crop has had generative AI at its fingertips the whole time.

My colleagues Ian Bogost and Lila Shroff both recently wrote articles about these students and the state of AI in education. (Ian, a university professor himself, wrote about college, while Lila wrote about high school.) Their articles were striking: It is clear that AI has been widely adopted, by students and faculty alike, yet the technology has also turned school into a kind of free-for-all.

I asked Lila and Ian to have a brief conversation about their work—and about where AI in education goes from here.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Lila Shroff: We’re a few years into AI in schools. Is the conversation maturing or changing in some way at universities?

Ian Bogost: Professors are less surprised that it exists, but there is maybe a bit of a blind spot to the state of adoption among students. I saw a panic in 2022, 2023—like, Oh my God, this can do anything. Or at least there were questions. Can this do everything? How much is my class at risk? Now I think there’s more of a sense of, Well, this thing still exists, but we have time. We don’t have to worry about it right away. And that might actually be a worse reaction than the original.

Lila: The blind-spot language rings true to the high-school environment too. I spoke to some high schoolers—granted this was quite a small sample—but basically it sounds like everybody is using this all the time for everything.

Ian: Not just for school, right? Anything they want to do, they’re asking ChatGPT now.

Lila: I was a sophomore in college when ChatGPT came out, so I witnessed some of this firsthand. There was much more anxiety—it felt like the rules were unclear. And I think both of our stories touched on the fact that for this incoming class of high-school and college seniors, they’ve barely had any of those four years without ChatGPT. Whatever sort of stigma or confusion that might have been there in earlier years is fading, and it’s becoming very much default and normalized.

Ian: Normalization is the thing that struck me the most. That is not a concept that I think the teachers have wrapped their heads around. Teachers and faculty also have been adopting AI carefully or casually—or maybe even in a more professional way, to write articles or letters of recommendation, which I’ve written about. There’s still this sense that it’s not really a part of their habit.

Lila: I looked into teachers at the K–12 level for the article I wrote. Three in 10 teachers are using AI weekly in some way.

Ian: Some kind of redesign of educational practice might be required, which is easy for me to say in an article. Instead of an answer, I have an approach to thinking about the answer that has been bouncing around in my brain. Are you familiar with the concept in software development called technical debt? In the software world, you make the decision about how to design or implement a system that feels good and right at the time. And maybe you know it’s going to be a bad idea in the long run, but for now, it makes sense and it is convenient. But you never get around to really making it better later on, and so you have all these nonoptimal aspects of your infrastructure.

That’s the state I feel like we’re in, at least in the university. It’s a little different in high school, especially in public high school, with these different regulatory regimes at work. But we accrued all this pedagogical debt, and not just since AI—there are aspects of teaching that we ought to be paying more attention to or doing better, like, this class needs to be smaller, or these kinds of assignments don’t work unless you have a lot of hands-on iterative feedback. We’ve been able to survive under the weight of pedagogical debt, and now something snapped. AI entered the scene and all of those bad or questionable—but understandable—decisions about how to design learning experiences are coming home to roost.

Lila: I agree that AI is a breaking point in education. One answer that seems to be emerging at the high-school level is a more practical, skills-based education. The College Board, for instance, has announced two new AP courses—AP Business and AP Cybersecurity. But there’s another group of people who are really concerned about how overreliance on these tools erodes critical-thinking skills, and maybe that means everyone should go read the classics and write their essays in cursive handwriting.

Ian: My young daughter has been going to this set of classes outside of school where she learned how to wire an outlet. We used to have shop class and metal class, and you could learn a trade, or at least begin to, in high school. A lot of that stuff has been disinvested. We used to touch more things. Now we move symbols around, and that’s kind of it.

I wonder if this all-or-nothing nature of AI use has something to do with that. If you had a place in your day as a high-school or college student where you just got to paint, or got to do on-the-ground work in the community, or apply the work you did in statistics class to solve a real-world problem—maybe that urge to just finish everything as rapidly as possible so you can get onto the next thing in your life would be less acute. The AI problem is a symptom of a bigger cultural illness, in a way.

Lila: Students are using AI exactly as it has been designed, right? They’re just making themselves more productive. If they were doing the same thing in an office, they might be getting a bonus.

Ian: Some of the students I talked to said, Your boss isn’t going to care how you get things done, just that they get done as effectively as possible. And they’re not wrong about that.

Lila: One student I talked to said she felt there was really too much to be done, and it was hard to stay on top of it all. Her message was, maybe slow down the pace of the work and give students more time to do things more richly.

Ian: The college students I talk to, if you slow it all down, they’re more likely to start a new club or practice lacrosse one more day a week. But I do love the idea of a slow-school movement to sort of counteract AI. That doesn’t necessarily mean excluding AI—it just means not filling every moment of every day with quite so much demand.

But you know, this doesn’t feel like the time for a victory of deliberateness and meaning in America. Instead, it just feels like you’re always going to be fighting against the drive to perform even more.

Education

The battle over US history reveals our education system’s key flaw | Katherine Kelaidis

No part of the Trump 2.0 agenda has been more revealing to the ideological intentions of the administration than the sustained efforts that insist upon a “pro-American” version of history. It is an effort that has taken many forms, including a recent letter sent by the White House to the Smithsonian announcing that there will be a review of the national museums’ semiquincentennial plans to “insure alignment with the president’s directive to celebrate American exceptionalism, remove divisive or partisan narratives, and restore confidence in our shared cultural institutions”. It is only the latest move in a broader campaign to commandeer the nation’s historical memory, a campaign mirrored in statehouses and school boards across the country, where history curricula have become a central front in the culture wars.

Unfortunately, the battle over the past – how we should understand it and, more importantly, how we should teach it – is a conflict for which most Americans today are woefully unprepared. That is because for more than two generations, the US educational system has systematically devalued the liberal arts in favor of vocationally oriented Stem education. By doing so, we have failed to accomplish the primary goal of education in a democracy: creating citizens capable of the difficult work of self-government. Of course vocational training and Stem education are vital to individual livelihoods and national prosperity. But when they become the sole focus of education, at the expense of the liberal arts, they leave citizens unprepared for the demands of democratic life.

The liberal arts derive their name from the Latin ars liberalis, which literally means “the trade skills of a free person”. For the ancient Greeks and Romans, and more importantly their Enlightenment admirers, citizenship was a trade, a vocation that required particular skills, just like any craft. Among the skills a citizen needed were critical thinking, a command of rhetoric and historical literacy. Importantly, historical literacy does not just mean memorizing dates and facts, but the ability to evaluate arguments, weigh interpretations against evidence, and connect past to present.

The decline of the humanities has also contributed to the collapse of empathy in American society. Literature and history, in particular, cultivate the ability to see the world through another’s eyes. Of course, empathy can be learned in other ways, but the humanities are uniquely powerful in diverse societies, where civic life depends on the capacity to empathize with those who are profoundly different from ourselves.

This is why the Trump administration and its allies have zeroed in on history education. They know what the enemies of free and compassionate societies have always known: people who understand what lies in the pages of history are far harder to oppress and far harder to coax into cruelty.

In the place of teaching history, they wish to place propaganda aimed at assuring that the critical thinking, compassion and perspective cultivated by real historical education are denied to America’s students. It is a kind of education American students have been denied for too long, which is why the American public is so vulnerable to this administration’s escalation.

Public education in the United States was not initially created to give students “job skills”, as so many on both sides of the political aisle today would have you believe. Teaching the skills necessary for a particular occupation, undeniably essential to economic health, was long viewed as the responsibility of private business and industry, which directly benefited from a trained workforce. Publicly funded schools existed to assure that students would have the skills needed to participate as responsible citizens of the republic. For this reason, the liberal arts, including history, were at the heart of the curriculum.

This began to change in the late 1950s, as cold war paranoia fueled a shift in educational priorities towards science, mathematics, technology and engineering aimed at preventing the US from falling behind the Soviet Union in these areas. These subjects, eventually branded Stem, would gain additional traction over the course of the next 60 years as changing economic winds seemed to suggest that career prospects in the rapidly expanding “technology” sector were the best assurance of a stable, if not prosperous, future. The fact that future employment prospects were even a consideration was evidence of another, less often articulated, change that was occurring.

Our understanding of education was being shifted to a view in which every part of the curriculum must have an immediate economic utility. It was, whether anyone realized it at the time or not, a dangerous and unconsidered change to the fundamental goals of education that assumed the assurance of economic prosperity required more public attention – and public funding – than the safeguarding of political liberty.

It was a gamble that has cost us dearly. The reason that so many of us have become increasingly susceptible to foreign propaganda, “fake news” and just plain bad arguments can be easily explained by the fact that much American curriculum simply fails to teach students how to think critically and deprives them of the important historical and geographic information that would allow them to spot when they are being deceived.

One of the great ironies of our era is that the economic benefits of Stem-focused education have proven to be an illusion. It is now clear that within a generation, many non-research based Stem jobs (and plenty of the research-based ones) are likely to simply vanish in the face of AI. And a public without a liberal arts education may simply lack the imagination to work their way out of this radical reordering of the economy. We will have traded our freedom for prosperity and ended up with neither.

But it is not too late. Maga’s assault on history can be the line in the sand – the moment we recognize what we have nearly lost. The surest way to defeat the dark forces now gathering in our politics is to make education once again serve its true purpose: preparing citizens for freedom. The liberal arts have always been at the heart of that mission. If we want to remain a free people, we must restore them to their rightful place at the center of American education.

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences3 months ago

Events & Conferences3 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoAstrophel Aerospace Raises ₹6.84 Crore to Build Reusable Launch Vehicle

-

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months ago

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months agoDonald Trump suggests US government review subsidies to Elon Musk’s companies

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoAERDF highlights the latest PreK-12 discoveries and inventions