AI Research

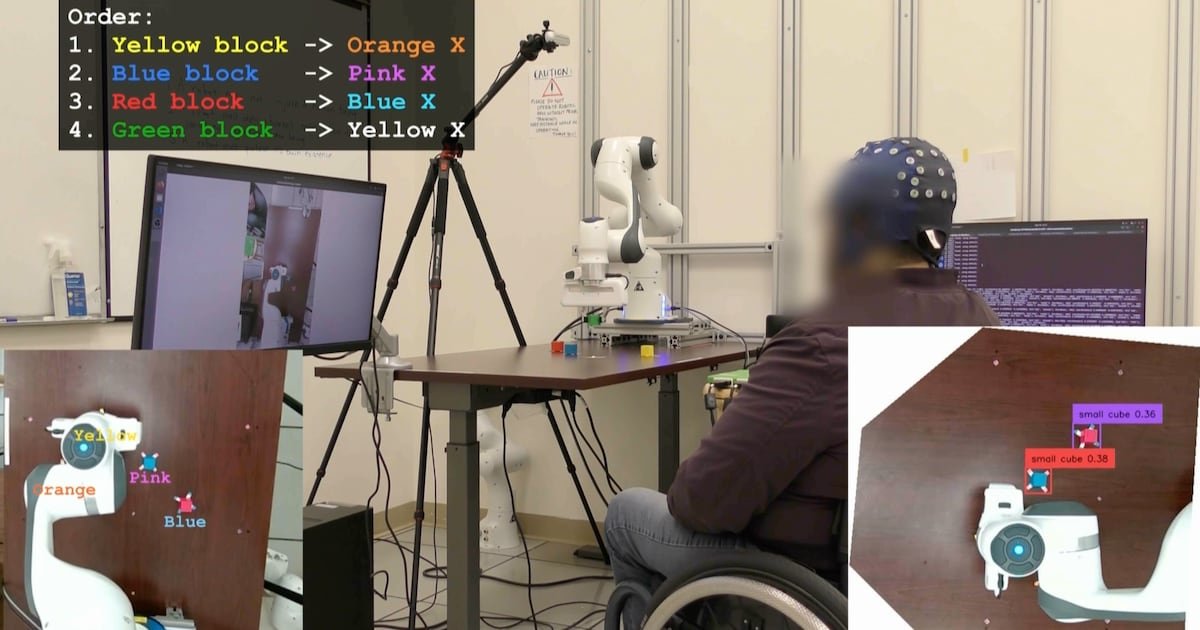

UCLA Researchers Enable Paralyzed Patients to Control Robots with Thoughts Using AI – CHOSUNBIZ – Chosun Biz

AI Research

MAIA platform for routine clinical testing: an artificial intelligence embryo selection tool developed to assist embryologists

Graham, M. E. et al. Assisted reproductive technology: Short- and long-term outcomes. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 65, 38–49 (2023).

Jiang, V. S. & Bormann, C. L. Artificial intelligence in the in vitro fertilization laboratory: a review of advancements over the last decade. Fertil. Steril. 120, 17–23 (2023).

Devine, K. et al. Single vitrified blastocyst transfer maximizes liveborn children per embryo while minimizing preterm birth. Fertil. Steril. 103, 1454–1460 (2015).

Tiitinen, A. Single embryo transfer: why and how to identify the embryo with the best developmental potential. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 33, 77–88 (2019).

Glatstein, I., Chavez-Badiola, A. & Curchoe, C. L. New frontiers in embryo selection. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 40, 223–234 (2023).

Gardner, D. K. & Schoolcraft, W. B. Culture and transfer of human blastocysts. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 11, 307–311 (1999).

Sciorio, R. & Meseguer, M. Focus on time-lapse analysis: blastocyst collapse and morphometric assessment as new features of embryo viability. Reprod. BioMed. Online. 43, 821–832 (2021).

Sundvall, L., Ingerslev, H. J., Knudsen, U. B. & Kirkegaard, K. Inter- and intra-observer variability of time-lapse annotations. Hum. Reprod. 28, 3215–3221 (2013).

Gallego, R. D., Remohí, J. & Meseguer, M. Time-lapse imaging: the state of the Art. Biol. Reprod. 101, 1146–1154 (2019).

VerMilyea, M. D. et al. Computer-automated time-lapse analysis results correlate with embryo implantation and clinical pregnancy: a blinded, multi-centre study. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 29, 729–736 (2014).

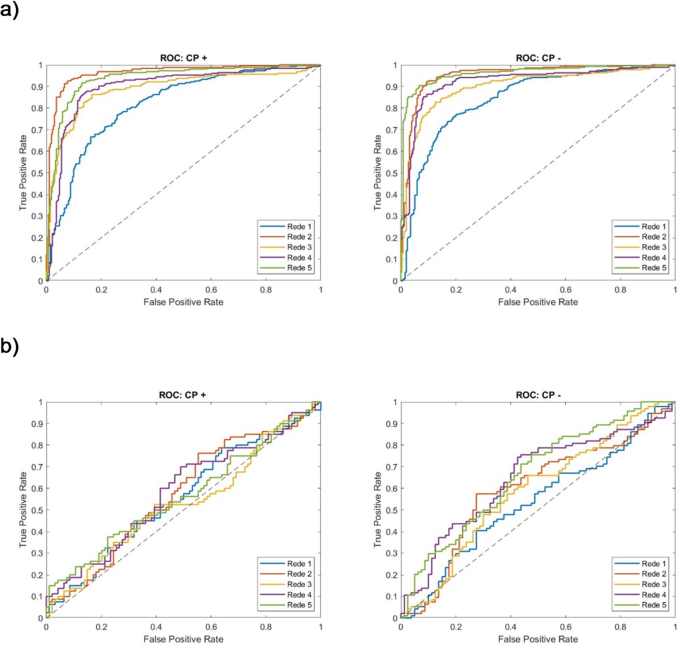

Chéles, D. S., Molin, E. A. D., Rocha, J. C. & Nogueira, M. F. G. Mining of variables from embryo morphokinetics, blastocyst’s morphology and patient parameters: an approach to predict the live birth in the assisted reproduction service. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 24, 470–479 (2020).

Rocha, C., Nogueira, M. G., Zaninovic, N. & Hickman, C. Is AI assessment of morphokinetic data and digital image analysis from time-lapse culture predictive of implantation potential of human embryos? Fertil. Steril. 110, e373 (2018).

Zaninovic, N. et al. Application of artificial intelligence technology to increase the efficacy of embryo selection and prediction of live birth using human blastocysts cultured in a time-lapse incubator. Fertil. Steril. 110, e372–e373 (2018).

Alegre, L. et al. First application of artificial neuronal networks for human live birth prediction on Geri time-lapse monitoring system blastocyst images. Fertil. Steril. 114, e140 (2020).

Bori, L. et al. An artificial intelligence model based on the proteomic profile of euploid embryos and blastocyst morphology: a preliminary study. Reprod. BioMed. Online. 42, 340–350 (2021).

Chéles, D. S. et al. An image processing protocol to extract variables predictive of human embryo fitness for assisted reproduction. Appl. Sci. 12, 3531 (2022).

Jacobs, C. K. et al. Embryologists versus artificial intelligence: predicting clinical pregnancy out of a transferred embryo who performs it better? Fertil. Steril. 118, e81–e82 (2022).

Lorenzon, A. et al. P-211 development of an artificial intelligence software with consistent laboratory data from a single IVF center: performance of a new interface to predict clinical pregnancy. Hum. Reprod. 39, deae108.581 (2024).

Fernandez, E. I. et al. Artificial intelligence in the IVF laboratory: overview through the application of different types of algorithms for the classification of reproductive data. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 37, 2359–2376 (2020).

Mendizabal-Ruiz, G. et al. Computer software (SiD) assisted real-time single sperm selection associated with fertilization and blastocyst formation. Reprod. BioMed. Online. 45, 703–711 (2022).

Fjeldstad, J. et al. Segmentation of mature human oocytes provides interpretable and improved blastocyst outcome predictions by a machine learning model. Sci. Rep. 14, 10569 (2024).

Khosravi, P. et al. Deep learning enables robust assessment and selection of human blastocysts after in vitro fertilization. NPJ Digit. Med. 2, 21 (2019).

Hickman, C. et al. Inner cell mass surface area automatically detected using Chloe eq™(fairtility), an ai-based embryology support tool, is associated with embryo grading, embryo ranking, ploidy and live birth outcome. Fertil. Steril. 118, e79 (2022).

Tran, D., Cooke, S., Illingworth, P. J. & Gardner, D. K. Deep learning as a predictive tool for fetal heart pregnancy following time-lapse incubation and blastocyst transfer. Hum. Reprod. 34, 1011–1018 (2019).

Rajendran, S. et al. Automatic ploidy prediction and quality assessment of human blastocysts using time-lapse imaging. Nat. Commun. 15, 7756 (2024).

Bormann, C. L. et al. Consistency and objectivity of automated embryo assessments using deep neural networks. Fertil. Steril. 113, 781–787e1 (2020).

Kragh, M. F. & Karstoft, H. Embryo selection with artificial intelligence: how to evaluate and compare methods? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 38, 1675–1689 (2021).

Cromack, S. C., Lew, A. M., Bazzetta, S. E., Xu, S. & Walter, J. R. The perception of artificial intelligence and infertility care among patients undergoing fertility treatment. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-024-03382-5 (2025).

Fröhlich, H. et al. From hype to reality: data science enabling personalized medicine. BMC Med. 16, 150 (2018).

Zhu, J. et al. External validation of a model for selecting day 3 embryos for transfer based upon deep learning and time-lapse imaging. Reprod. BioMed. Online. 47, 103242 (2023).

Yelke, H. K. et al. O-007 Simplifying the complexity of time-lapse decisions with AI: CHLOE (Fairtility) can automatically annotate morphokinetics and predict blastulation (at 30hpi), pregnancy and ongoing clinical pregnancy. Hum. Reprod. 37, deac104.007 (2022).

Papatheodorou, A. et al. Clinical and practical validation of an end-to-end artificial intelligence (AI)-driven fertility management platform in a real-world clinical setting. Reprod. BioMed. Online. 45, e44–e45 (2022).

Salih, M. et al. Embryo selection through artificial intelligence versus embryologists: a systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Open hoad031 (2023).

Nunes, K. et al. Admixture’s impact on Brazilian population evolution and health. Science. 388(6748), eadl3564 (2025).

Jackson-Bey, T. et al. Systematic review of Racial and ethnic disparities in reproductive endocrinology and infertility: where do we stand today? F&S Reviews. 2, 169–188 (2021).

Kassi, L. A. et al. Body mass index, not race, May be associated with an alteration in early embryo morphokinetics during in vitro fertilization. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 38, 3091–3098 (2021).

Pena, S. D. J., Bastos-Rodrigues, L., Pimenta, J. R. & Bydlowski, S. P. DNA tests probe the genomic ancestry of Brazilians. Braz J. Med. Biol. Res. 42, 870–876 (2009).

Fraga, A. M. et al. Establishment of a Brazilian line of human embryonic stem cells in defined medium: implications for cell therapy in an ethnically diverse population. Cell. Transpl. 20, 431–440 (2011).

Amin, F. & Mahmoud, M. Confusion matrix in binary classification problems: a step-by-step tutorial. J. Eng. Res. 6, 0–0 (2022).

Magdi, Y. et al. Effect of embryo selection based morphokinetics on IVF/ICSI outcomes: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 300, 1479–1490 (2019).

Guo, Y. H., Liu, Y., Qi, L., Song, W. Y. & Jin, H. X. Can time-lapse incubation and monitoring be beneficial to assisted reproduction technology outcomes? A randomized controlled trial using day 3 double embryo transfer. Front. Physiol. 12, 794601 (2022).

Giménez, C., Conversa, L., Murria, L. & Meseguer, M. Time-lapse imaging: morphokinetic analysis of in vitro fertilization outcomes. Fertil. Steril. 120, 228–227 (2023).

Vitrolife EmbryoScope + time-lapse system. (2023). https://www.vitrolife.com/products/time-lapse-systems/embryoscopeplus-time-lapse-system/.

Lagalla, C. et al. A quantitative approach to blastocyst quality evaluation: morphometric analysis and related IVF outcomes. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 32, 705–712 (2015).

Rocha, J. C. et al. A method based on artificial intelligence to fully automatize the evaluation of bovine blastocyst images. Sci. Rep. 7, 7659 (2017).

Chavez-Badiola, A. et al. Predicting pregnancy test results after embryo transfer by image feature extraction and analysis using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 10, 4394 (2020).

Matos, F. D., Rocha, J. C. & Nogueira, M. F. G. A method using artificial neural networks to morphologically assess mouse blastocyst quality. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 56, 15 (2014).

Wang, S., Zhou, C., Zhang, D., Chen, L. & Sun, H. A deep learning framework design for automatic blastocyst evaluation with multifocal images. IEEE Access. 9, 18927–18934 (2021).

Berntsen, J., Rimestad, J., Lassen, J. T., Tran, D. & Kragh, M. F. Robust and generalizable embryo selection based on artificial intelligence and time-lapse image sequences. PLoS One. 17, e0262661 (2022).

Fruchter-Goldmeier, Y. et al. An artificial intelligence algorithm for automated blastocyst morphometric parameters demonstrates a positive association with implantation potential. Sci. Rep. 13, 14617 (2023).

Illingworth, P. J. et al. Deep learning versus manual morphology-based embryo selection in IVF: a randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial. Nat. Med. 30, 3114–3120 (2024).

Kanakasabapathy, M. K. et al. Development and evaluation of inexpensive automated deep learning-based imaging systems for embryology. Lab. Chip. 19, 4139–4145 (2019).

Loewke, K. et al. Characterization of an artificial intelligence model for ranking static images of blastocyst stage embryos. Fertil. Steril. 117, 528–535 (2022).

Hengstschläger, M. Artificial intelligence as a door opener for a new era of human reproduction. Hum. Reprod. Open hoad043 (2023).

Lassen Theilgaard, J., Fly Kragh, M., Rimestad, J., Nygård Johansen, M. & Berntsen, J. Development and validation of deep learning based embryo selection across multiple days of transfer. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 4235 (2023).

Lozano, M. et al. P-301 Assessment of ongoing clinical outcomes prediction of an AI system on retrospective SET data, Human Reprod. 38(Issue Supplement_1), dead093.659. (2023).

Collins, G. S. et al. TRIPOD + AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 385, e078378 (2024).

Abdolrasol, M. G. M. et al. Artificial neural networks based optimization techniques: a review. Electronics 10, 2689 (2021).

Yuzer, E. O. & Bozkurt, A. Instant solar irradiation forecasting for solar power plants using different ANN algorithms and network models. Electr. Eng. 106, 3671–3689 (2024).

Guariso, G. & Sangiorgio, M. Improving the performance of multiobjective genetic algorithms: an elitism-based approach. Information 11, 587 (2020).

García-Pascual, C. M. et al. Optimized NGS approach for detection of aneuploidies and mosaicism in PGT-A and imbalances in PGT-SR. Genes 11, 724 (2020).

AI Research

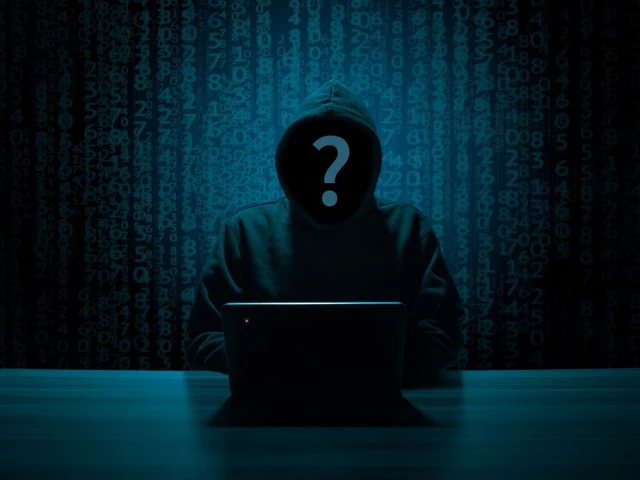

Hackers exploit hidden prompts in AI images, researchers warn

Cybersecurity firm Trail of Bits has revealed a technique that embeds malicious prompts into images processed by large language models (LLMs). The method exploits how AI platforms compress and downscale images for efficiency. While the original files appear harmless, the resizing process introduces visual artifacts that expose concealed instructions, which the model interprets as legitimate user input.

In tests, the researchers demonstrated that such manipulated images could direct AI systems to perform unauthorized actions. One example showed Google Calendar data being siphoned to an external email address without the user’s knowledge. Platforms affected in the trials included Google’s Gemini CLI, Vertex AI Studio, Google Assistant on Android, and Gemini’s web interface.

Read More: Meta curbs AI flirty chats, self-harm talk with teens

The approach builds on earlier academic work from TU Braunschweig in Germany, which identified image scaling as a potential attack surface in machine learning. Trail of Bits expanded on this research, creating “Anamorpher,” an open-source tool that generates malicious images using interpolation techniques such as nearest neighbor, bilinear, and bicubic resampling.

From the user’s perspective, nothing unusual occurs when such an image is uploaded. Yet behind the scenes, the AI system executes hidden commands alongside normal prompts, raising serious concerns about data security and identity theft. Because multimodal models often integrate with calendars, messaging, and workflow tools, the risks extend into sensitive personal and professional domains.

Also Read: Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang says AI boom far from over

Traditional defenses such as firewalls cannot easily detect this type of manipulation. The researchers recommend a combination of layered security, previewing downscaled images, restricting input dimensions, and requiring explicit confirmation for sensitive operations.

“The strongest defense is to implement secure design patterns and systematic safeguards that limit prompt injection, including multimodal attacks,” the Trail of Bits team concluded.

AI Research

When AI Freezes Over | Psychology Today

A phrase I’ve often clung to regarding artificial intelligence is one that is also cloaked in a bit of techno-mystery. And I bet you’ve heard it as part of the lexicon of technology and imagination: “emergent abilities.” It’s common to hear that large language models (LLMs) have these curious “emergent” behaviors that are often coupled with linguistic partners like scaling and complexity. And yes, I’m guilty too.

In AI research, this phrase first took off after a 2022 paper that described how abilities seem to appear suddenly as models scale and tasks that a small model fails at completely, a larger model suddenly handles with ease. One day a model can’t solve math problems, the next day it can. It’s an irresistible story as machines have their own little Archimedean “eureka!” moments. It’s almost as if “intelligence” has suddenly switched on.

But I’m not buying into the sensation, at least not yet. A newer 2025 study suggests we should be more careful. Instead of magical leaps, what we’re seeing looks a lot more like the physics of phase changes.

Ice, Water, and Math

Think about water. At one temperature it’s liquid, at another it’s ice. The molecules don’t become something new—they’re always two hydrogens and an oxygen—but the way they organize shifts dramatically. At the freezing point, hydrogen bonds “loosely set” into a lattice, driven by those fleeting electrical charges on the hydrogen atoms. The result is ice, the same ingredients reorganized into a solid that’s curiously less dense than liquid water. And, yes, there’s even a touch of magic in the science as ice floats. But that magic melts when you learn about Van der Waals forces.

The same kind of shift shows up in LLMs and is often mislabeled as “emergence.” In small models, the easiest strategy is positional, where computation leans on word order and simple statistical shortcuts. It’s an easy trick that works just enough to reduce error. But scale things up by using more parameters and data, and the system reorganizes. The 2025 study by Cui shows that, at a critical threshold, the model shifts into semantic mode and relies on the geometry of meaning in its high-dimensional vector space. It isn’t magic, it’s optimization. Just as water molecules align into a lattice, the model settles into a more stable solution in its mathematical landscape.

The Mirage of “Emergence”

That 2022 paper called these shifts emergent abilities. And yes, tasks like arithmetic or multi-step reasoning can look as though they “switch on.” But the model hasn’t suddenly “understood” arithmetic. What’s happening is that semantic generalization finally outperforms positional shortcuts once scale crosses a threshold. Yes, it’s a mouthful. But happening here is the computational process that is shifting from a simple “word position” in a prompt (like, the cat in the _____) to a complex, hyperdimensional matrix where semantic associations across thousands of dimensions create amazing strength to the computation.

And those sudden jumps? They’re often illusions. On simple pass/fail tests, a model can look stuck at zero until it finally tips over the line and then it seems to leap forward. In reality, it was improving step by step all along. The so-called “light-bulb moment” is really just a quirk of how we measure progress. No emergence, just math.

Why “Emergence” Is So Seductive

Why does the language of “emergence” stick? Because it borrows from biology and philosophy. Life “emerges” from chemistry as consciousness “emerges” from neurons. It makes LLMs sound like they’re undergoing cognitive leaps. Some argue emergence is a hallmark of complex systems, and there’s truth to that. So, to a degree, it does capture the idea of surprising shifts.

But we need to be careful. What’s happening here is still math, not mind. Calling it emergence risks sliding into anthropomorphism, where sudden performance shifts are mistaken for genuine understanding. And it happens all the time.

A Useful Imitation

The 2022 paper gave us the language of “emergence.” The 2025 paper shows that what looks like emergence is really closer to a high-complexity phase change. It’s the same math and the same machinery. At small scales, positional tricks (word sequence) dominate. At large scales, semantic structures (multidimensional linguistic analysis) win out.

No insight, no spark of consciousness. It’s just a system reorganizing under new constraints. And this supports my larger thesis: What we’re witnessing isn’t intelligence at all, but anti-intelligence, a powerful, useful imitation that mimics the surface of cognition without the interior substance that only a human mind offers.

Artificial Intelligence Essential Reads

So the next time you hear about an LLM with “emergent ability,” don’t imagine Archimedes leaping from his bath. Picture water freezing. The same molecules, new structure. The same math, new mode. What looks like insight is just another phase of anti-intelligence that is complex, fascinating, even beautiful in its way, but not to be mistaken for a mind.

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences3 months ago

Events & Conferences3 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months ago

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months agoDonald Trump suggests US government review subsidies to Elon Musk’s companies