AI Insights

Tolstoy’s Complaint: Mission Command in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

What will become of battlefield command in the years ahead? This question is at the heart of the US Army’s once-in-a-generation reforms now underway. In search of answers, the Army looks to Ukraine. Events there suggest at least two truths. One is that decentralized command, which the US Army calls mission command and claims as its mode, will endure as a virtue. A second is that future commanders will use artificial intelligence to inform every decision—where to go, whom to kill, and whom to save. The recently announced Army Transformation Initiative indicates the Army intends to act on both.

But from these lessons there arises a different dilemma: How can an army at once preserve a culture of decentralized command and integrate artificial intelligence into its every task? Put another way, if at all echelons commanders rely on artificial intelligence to inform decisions, do they not risk just another form of centralization, not at the top, but within an imperfect model? To understand this dilemma and to eventually resolve it, the US Army would do well to look once again to the Ukrainian corner of the map, though this time as a glance backward two centuries, so that it might learn from a young redleg in Crimea named Leo Tolstoy.

What Tolstoy Saw

Before he became a literary titan, Leo Tolstoy was a twenty-something artillery officer. In 1854 he found himself in besieged port of Sevastopol, then under relentless French and British shelling, party to the climax of the Crimean War. When not tending to his battery on the city’s perilous Fourth Bastion, Tolstoy wrote dispatches about life under fire for his preferred journal in Saint Petersburg, The Contemporary. These dispatches, read across literate Russia for their candor and craft, made Tolstoy famous. They have since been compiled as The Sebastopol Sketches and are considered by many to be the first modern war reportage. Their success confirmed for Tolstoy that to write was his life’s calling, and when the Crimean War ended, he left military service so that he might do so full-time.

But once a civilian Tolstoy did not leave war behind, at least not as a subject matter. Until he died, he mined his time in uniform for the material of his fiction. In that fiction, most prominently the legendary accounts of the battles of Austerlitz and Borodino found in War and Peace, one can easily detect what he thought of command. Tolstoy’s contention is that the very idea of command itself is practically a fiction, so tenuous is the relationship between what commanders visualize, describe, and direct and what in fact happens on the battlefield. The worst officers in Tolstoy’s stories do great harm by vainly supposing they understand battles at hand when they in fact haven’t the faintest idea of what’s going on. The best officers are at peace with their inevitable ignorance and rather than fighting it, gamely project a calm that inspires their men. Either way, most officers wander the battlefield, blinded by gun smoke or folds in the earth, only later making up stories to explain what happened, stories others wrongly take as credible witness testimony.

Command or Hallucination?

Students of war may wonder whether Tolstoy was saying anything Carl von Clausewitz had not already said in On War, published in 1832. After all, there Clausewitz made famous allowances for the way the unexpected and the small both shape battlefield outcomes, describing their effects as “friction,” a term that still enjoys wide use in the US military today. But the friction metaphor itself already hints at one major difference between Clausewitz’s understanding of battle and Tolstoy’s. For Clausewitz all the things that go sideways in war amount to friction impeding the smooth operation of a machine at work on the battlefield, a machine begotten of an intelligent design and consisting of interlocking parts that fail by exception. As Tolstoy sees it, there is no such machine, except in the imagination of largely ineffectual senior leaders, who, try as they might, cannot realize their designs on the battlefield.

Tolstoy thus differed from Clausewitz by arguing that commanders not only fail to anticipate friction, but outright hallucinate. They see patterns on the battlefield where there are none and causes where there is only coincidence. In War and Peace, Pyotr Bagration seeks permission to start the battle at Austerlitz when it is already lost, Moscow burns in 1814 not because Kutuzov ordered it but because the firefighters fled the city, and Russians’ masterful knockout flank at Tarutino occurs not in accordance with a preconceived plan but by an accident of logistics. Yet historians and contemporaries alike credit Bagration and Kutuzov for the genius of these events—to say nothing of Napoleon, whom Tolstoy casts as a deluded egoist, “a child, who, holding a couple of strings inside a carriage, thinks he is driving it.”

Why then, per Tolstoy, do the commanders and historians credit such plans with unrelated effects? Tolstoy answers this in a typical philosophical passage of War and Peace: “The human mind cannot grasp the causes of events in their completeness,” but “the desire to find those causes is implanted in the human soul.” People, desirous of coherence but unable to espy the many small causes of events, instead see grand things and great men that are not there. Here Tolstoy makes a crucial point—it is not that there are no causes of events, just that the causes are too numerous and obscure for humans to know. These causes Tolstoy called “infinitesimals,” and to find them one must “leave aside kings, ministers, and generals” and instead study “the small elements by which the masses are moved.”

This is Tolstoy’s complaint. He lodged it against the great man theorists of history, then influential, who supposed great men propelled human events through genius and will. But it also can be read as a strong case for mission command, for Tolstoy’s account of war suggests that not only is a decentralized command the best sort of command—it is the only authentic command at all. Everything else is illusory. High-echelon commanders’ distance from the fight, from the level of the grunt or the kitchen attendant, allows their hallucinations to persist unspoiled by reality far longer than those below them in rank. The leader low to the ground is best positioned to integrate the infinitesimals into an understanding of the battlefield. That integration, as Isaiah Berlin writes in his great Tolstoy essay “The Hedgehog and Fox,” is more so “artistic-psychological” work than anything else. And what else are the “mutual trust” and “shared understanding,” which Army doctrine deems essential to mission command, but the products of an artful, psychological process?

From Great Man Theory to Great Model Theory

Perhaps no one needs Tolstoy to appreciate mission command. Today American observers see everywhere on the battlefields of Ukraine proof of its wisdom. They credit the Ukrainian armed forces with countering their Russian opponents’ numerical and material superiority by employing more dynamic, decentralized command and control, which they liken to the US Army’s own style. Others credit Ukrainians’ use of artificial intelligence for myriad battlefield functions, and here the Ukrainians are far ahead of the US Army. Calls abound to catch up by integrating artificial intelligence into data-centric command-and-control tools, staff work, and doctrine. The relationship between these two imperatives, to integrate artificial intelligence and preserve mission command, has received less attention.

At first blush, artificial intelligence seems a convincing answer to Tolstoy’s complaint. In “The Hedgehog and the Fox” Isaiah Berlin summarized that complaint this way:

Our ignorance is due not to some inherent inaccessibility of the first causes, only their multiplicity, the smallness of the ultimate units, and our own inability to see and hear and remember and record and co-ordinate enough of the available material. Omniscience is in principle possible even to empirical beings, but, of course, in practice unattainable.

Can one come up with a better pitch for artificial intelligence than that? Is not artificial intelligence’s alleged value proposition for the commander its ability to integrate all the Tolstoyan infinitesimals, those “ultimate units,” then project it, perhaps on a wearable device, for quick reference by the dynamic officer pressed for time by an advancing enemy? Put another way, can’t a great model deliver on the battlefield what a great man couldn’t?

The trouble is threefold. Whatever model or computer vision or multimodal system we call “artificial intelligence” and incorporate into a given layer of a command-and-control platform represents something like one mind, but not many minds, so each instance wherein a leader outsources analysis to that artificial intelligence is another instance of centralization. Second, the models we have are disposed to patterns and to hubris, so are more a replication than a departure from the hallucinating commanders Tolstoy so derided. Finally, leaders may reject the evidence of their eyes and ears in deference to artificial intelligence because it enjoys the credibility of dispassionate computation, thereby forgoing precisely the ground-level inputs that Tolstoy pointed out were most important for understanding battle.

Consider the centralization problem. Different models may be in development for different uses across the military, but the widespread fielding of any artificial intelligence–enabled command-and-control system risks proliferating the same model across the operational army. If the purpose of mission command were strictly to hasten battlefield decisions by replicating the mind of a higher command within junior leaders, then the threat of centralization would be irrelevant because artificial intelligence would render mission command obsolete. But Army Doctrinal Pamphlet 6-0 lists as mission command’s purpose also the levering of “subordinate ingenuity”—something that centralization denies. In aggregate one risks giving every user the exact same coach, if not the exact same commander, however brilliant that coach or commander might be.

Such a universal coach, like a universal compass or rifle, might not be so bad, were it not for the tendency of that universal coach to hallucinate. That large language models make things up and then confidently present them as truth is not news, but it is also not going away. Nor is those models’ basic function, which is to seek patterns and then extend them. Computer vision likewise produces false positives. This “illusion of thinking,” to paraphrase recent research, severely limits the capacity of artificial intelligence to tackle novel problems or process novel environments. Tolstoy observes that during the invasion of Russia “a war began which did not follow any previous traditions of war,” yet Napoleon “did not cease to complain . . . that the war was being carried on contrary to all the rules—as if there were any rules for killing people.” In this way Tolstoy ascribes Napoleon’s disastrous defeat at Borodino precisely to the sort of error artificial intelligence is prone to make—the faulty assumption that the rules that once applied extend forward mechanically. There is thus little difference between the sort of prediction for which models are trained and the picture of Napoleon in War and Peace on the eve of his arrival in Moscow. He imagined a victory that the data on which he had trained indicated he ought expect but that ultimately eludes him.

Such hallucinations are compounded by models’ systemic overconfidence. Research suggests that, like immature officers, models prefer to confidently proffer an answer than confess they just do not know. It is then not hard to imagine artificial intelligence processing incomplete reports of enemy behavior on the battlefield, deciding that the behavior conforms to a pattern, filling in gaps the observed data leaves, then confidently predicting an enemy course of action disproven by what a sergeant on the ground is seeing. It is similarly not hard to imagine a commander directing, at the suggestion of an artificial intelligence model, the creation of an engagement area anchored to hallucinated terrain or queued by a nonexistent enemy patrol. In the aggregate, artificial intelligence might effectively imagine entire scenarios like the ones on which it was trained playing out on a battlefield where it can detect little more than the distant, detonating pop of an explosive-laden drone.

To be fair, uniformed advocates of artificial intelligence have said explicitly that no one wants to replace human judgment. Often those advocates speak instead of artificial intelligence informing, enhancing, enabling, or otherwise making more efficient human commanders. Besides, any young soldier will point out that human commanders make all the same mistakes. Officers need no help from machines to spook at a nonexistent enemy or to design boneheaded engagement areas. So what’s the big deal with using artificial intelligence?

The issue is precisely that we regard artificial intelligence as more than human and so show it a deference researchers call “automation bias.” It’s all but laughable today to ascribe to any human the genius for seeing through war’s complexity that great man theorists once vested in Napoleon. But now many invest similar faith in the genius of artificial intelligence. Sam Altman of OpenAI refers to his project as the creation of “superintelligence.” How much daylight is there between the concept of superintelligence and the concept of the great man? We thus risk treating artificial intelligence as the Napoleon that Napoleon could not be, the genius integrator of infinitesimals, the protagonist of the histories that Tolstoy so effectively demolished in War and Peace. And if we regard artificial intelligence as the great man of the history, can we expect a young lieutenant to resist its recommendations?

What Is to Be Done?

Artificial intelligence, in its many forms, is here to stay. The Army cannot afford in this interwar moment a Luddite reflex. It must integrate artificial intelligence into its operations. Anybody who has attempted to forecast when a brigade will be ready for war or when a battalion will need fuel resupply or when a soldier will need a dental checkup knows how much there is to be gained from narrow artificial intelligence, which promises to gain immense efficiencies in high-iteration, structured, context-independent tasks. Initiatives like Next Generation Command and Control promise as much. But the risks to mission command posed by artificial intelligence are sizable. Tolstoy’s complaint is of great use to the Army as it seeks to understand and mitigate those risks.

The first way to mitigate the risk artificial intelligence poses to mission command is to limit the use of it those high-volume, simple tasks. Artificial intelligence is ill-suited for low-volume, highly complex, context-dependent, deeply human endeavors—a good description of warfare—and so its role in campaign design, tactical planning, the analysis of the enemy, and the leadership of soldiers should be small. Its use in such endeavors is limited to expediting calculations of the small inputs human judgment requires. This notion of human-machine teaming in war is not new (it has been explored well by others, including Major Amanda Collazzo via the Modern War Institute). But amid excitement for it, the Army risks forgetting that it must carefully draw and jealously guard the boundary between human and machine. It must do so not only for ethical reasons, but because, as Tolstoy showed to such effect, command in battle humbles the algorithmic mind—of man or machine. Put in Berlin’s terms, command remains “artistic-psychological” work, and that work, even now, remains human work. Such caution does not require a ban on machine learning and artificial intelligence in simulations or wargames, which would be self-sabotage, but it does require that officers check any temptation to outsource the authorship of campaigns or orders to a model—something which sounds obvious now, but soon may not.

The second way is to program into the instruction of Army leaders a healthy skepticism of artificial intelligence. This might be done first by splitting the instruction of students into analog and artificial intelligence–enabled segments, not unlike training mortarmen to plan fire missions with a plotting board as well as a ballistic computer. Officers must first learn to write plans and direct their execution without aid before incorporating artificial intelligence into the process. Their ability to do so must be regularly recertified throughout their careers. Classes on machine learning that highlight the dependency of models on data quality must complement classes on intelligence preparation of the battlefield. Curriculum designers will rightly point out that curricula are already overstuffed, but if artificial intelligence–enabled command and control is as revolutionary as its proponents suggest, it demands a commensurate change in the way we instruct our commanders.

The third way to mitigate the risks posed is to program the same skepticism of artificial intelligence into training. When George Marshall led the Infantry School during the interwar years, he and fellow instructor Joseph Stilwell forced students out of the classroom and into the field for unscripted exercises, providing them bad maps so as to simulate the unpredictability of combat. Following their example, the Army should deliberately equip leaders during field exercises and wargames with hallucinatory models. Those leaders should be evaluated on their ability to recognize when the battlefield imagined by their artificial intelligence–enabled command-and-control platforms and the battlefield they see before them differ. And when training checklists require that for a unit to be fully certified in a task it must perform that task under dynamic, degraded conditions, “degraded” must come to include hallucinatory or inoperable artificial intelligence.

Even then, Army leaders must never forget what Tolstoy teaches us: that command is a contingent, human endeavor. Often battles represent idiosyncratic problems of their own, liable to defy patterns. Well-trained young leaders’ proximity to those problems is an asset rather than a liability. For that proximity they can spot on the battlefield infinitesimally small things that great data ingests cannot capture. A philosophy of mission command, however fickle and at times frustrating, best accommodates the insights that arise from that proximity. Only then can the Army see war’s Tolstoyan infinitesimals through the gun smoke and have any hope of integrating them.

Theo Lipsky is an active duty US Army captain. He is currently assigned as an instructor to the Department of Social Sciences at the US Military Academy at West Point. He holds a master of public administration from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and a bachelor of science from the US Military Academy. His writing can be found at theolipsky.substack.com.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Zoe Morris, US Army

AI Insights

Up 300%, This Artificial Intelligence (AI) Upstart Has Room to Soar

Get to know an artificial intelligence stock that other investors are just catching on to.

One stock that is not on the radar of most mainstream investors has quietly risen by more than 300% since April 2025, moving from an intraday low of $6.27 per share all the way to an intraday high of $26.43 per share in late August. Previously, the stock had peaked at over $50 per share in 2024. What changed? It became an artificial intelligence (AI) stock after suffering in the downturn of the electric vehicle market. Most investors probably haven’t caught on yet, and, until recently, the company may not have recognized the AI opportunity it had, either.

I’m referring to Aehr Test Systems (AEHR -2.81%), and I’ll explain why this company is crucial to the AI and data center industries. There is still a significant opportunity for investors to capitalize on, even if they missed the bottom.

Why is Aehr critical to AI?

Here is the 30,000-foot view. When companies, notably hyperscalers, build massive data centers full of tens of millions, and sometimes hundreds of millions, of semiconductors (chips), they must ensure that they are reliable. High failure rates are extremely costly in terms of remediation, labor, downtime, and replacements. If the company selling the chips has a high failure rate, its competitors can gain traction. Aehr Test Systems provides the necessary reliability testing systems.

Their importance cannot be understated. The latest chips are stackable (multiple layers of chips forming one unit), which allows for exponentially more processing power. However, there is a catch. Many times, they are a “single point of failure.” In other words, if one chip in the stack fails, the entire stack fails. The importance of reliability testing has increased by an order of magnitude as a result. And now Aehr is the hot name that could become a stock market darling again.

Image source: Getty Images.

Is Aehr stock a buy now?

You have probably heard about the massive data centers that the “hyperscalers,” companies like Meta Platforms, Amazon, Elon Musk’s xAI, and other tech giants, are building across the country and the world. In fact, trying to keep up with all of the announcements of new projects would make your head spin. In many cases, the data center campus spans more than a square mile and contains hundreds of thousands of chips. Elon Musk’s xAI project, dubbed “Colossus,” is said to require over a million GPUs in the end.

As shown below, the number of hyperscale data centers is soaring with no end in sight.

Source: Statista.

This number increased to more than 1,100 at the end of 2024, nearly doubling over the past five years. The demand is primarily driven by artificial intelligence, which is why Aehr is now an “AI stock” — and the reason its share price took off and could continue higher over the long term.

Aehr still faces serious challenges. Its revenue fell from $66 million in fiscal 2024 to $59 million in fiscal 2025. It slipped from an operating profit of $10 million to a loss of $6 million over that period as the company undertook the challenging task of refocusing its business. However, investors who dig deeper see a very encouraging sign. The company’s backlog (orders that have been placed, but not yet fulfilled) jumped to $15 million from $7 million. Aehr also announced several orders received from major hyperscalers over the last couple of months.

It’s challenging to value Aehr stock at this time. The company is in a transition period, and while the AI market looks hugely promising, it is still a work in progress. In its heyday, the stock’s valuation peaked at 31 times sales, and as recently as August 2023 it traded for 24 times sales compared to 12 times sales today. The AI market could be a gold mine for Aehr, and Aehr stock looks like a terrific buy for investors.

Bradley Guichard has positions in Aehr Test Systems and Amazon. The Motley Fool has positions in and recommends Amazon and Meta Platforms. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.

AI Insights

Augment AI startup secures $85M for logistics teammate

Given these persistent challenges, could artificial intelligence (AI) be the answer? By automating repetitive tasks—such as invoice validation, exception alerts, and document processing—AI has the potential to streamline workflows, reduce errors, and free up teams to focus on strategic decision-making.

A recent report by research firm Deep Analysis, sponsored by document automation specialist Hyperscience, sheds light on the current state of AI readiness in T&L back-office functions. Titled “Market Momentum Index: AI Readiness in Transportation and Logistics Back-Office Operations,” the report drew on findings from a survey of T&L professionals to reveal both the challenges and opportunities for automation and AI adoption. (For more information about the research and methodology, see sidebar, “About the research.”)

This article summarizes some of the key findings and offers some actionable recommendations for supply chain professionals looking to harness the power of AI to drive efficiency and competitiveness.

THE CRITICAL ROLE OF THE BACK OFFICE

Back-office operations are the administrative core of supply chain processes, encompassing tasks such as order processing, inventory management, billing, compliance documentation, and communications with vendors and carriers. While these tasks are not visible to end consumers, they are vital to maintaining the smooth flow of goods and ensuring on-time deliveries. Furthermore, these operations are typically complex, involving numerous transactions and partners, and, as a result, are often plagued by fragmented processes, duplicated efforts, and misaligned data. Yet, most transportation and logistics companies still depend on manual processes and paper-based systems for their back-office operations, which often lead to errors, delays, and inefficiencies.

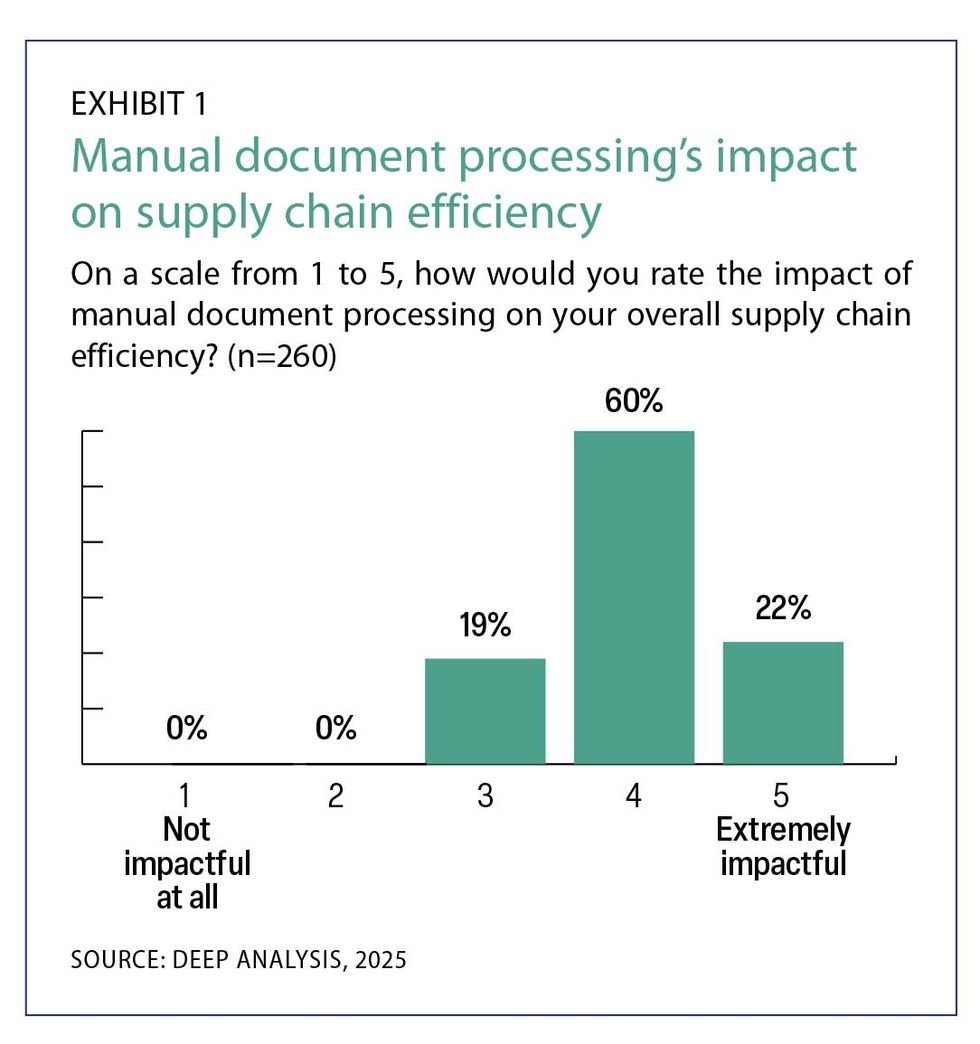

For example, the industry relies heavily on documents such as invoices, bills of lading, shipment tracking forms, and compliance records. Many organizations, however, use manual or semi-automated processes to manage these documents. Survey respondents indicated that the manual handling of supply chain documentation is a significant challenge that can have a large impact on overall supply chain efficiency (see Exhibit 1). For instance, missing or incorrect paperwork can cause customs delays, incur fines, or disrupt critical supply chain timelines. Additionally, document handling involves multiple touchpoints, which increases the risk of errors and operational delays. Furthermore, the lack of standardized document formats complicates data sharing and collaboration.

The survey found that many companies have implemented digital tools such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, supply chain management (SCM) systems, transportation management systems (TMS), and warehouse management systems (WMS). These systems were initially marketed as comprehensive solutions capable of automating business processes, improving efficiency, and providing real-time data visibility. However, their effectiveness has been limited by several key challenges. First, high implementation costs and complex integrations often lead to partial deployments, where critical functions remain unautomated. Second, rigid system architectures struggle to adapt to dynamic business needs, forcing employees to rely on manual workarounds—particularly in Excel—to fill functionality gaps. This reliance on spreadsheets introduces high data-entry error rates, inconsistent reporting, and limited data visualization capabilities. Additionally, ineffective user training and resistance to change further hinder adoption, leaving many organizations unable to fully leverage these systems. As a result, despite their potential, ERP, WMS, and similar tools frequently fall short of delivering the promised operational transformation.

THE GROWING INTEREST IN AI

Given the lack of success with other technology tools, there is a perception that supply chain organizations in general—and T&L firms in particular—might be resistant to or uninterested in AI. So it came as a bit of a surprise that the survey results indicated a growing interest in automation and AI within the T&L sector. Over 70% of respondents expressed a willingness to invest in AI-optimized systems, recognizing the potential for these technologies to transform back-office operations.

Of those respondents whose organizations were already using AI, 98% said they view the technology as useful, important, or vital. As Exhibit 2 shows, these respondents are currently employing AI to accomplish a wide range of goals. The report highlights several key areas where AI adds value, such as:

1. Improved decision-making (31%): AI can analyze large volumes of complex data—such as real-time traffic patterns, weather conditions, shipment tracking, and historical trends—to optimize supply chain decisions.

2. Error reduction (28%): For back-office tasks such as data entry, invoice processing, and document management, AI can automate repetitive processes, drastically reducing human error.

3. Enhanced data quality (37%): AI improves data quality by ensuring consistency, standardization, and accuracy, making the data more reliable for decision-making purposes.

Going forward, automation and AI have the potential to reshape the industry, enabling companies to reimagine workflows, prioritize sustainability, and enhance collaboration.

BARRIERS TO AI ADOPTION

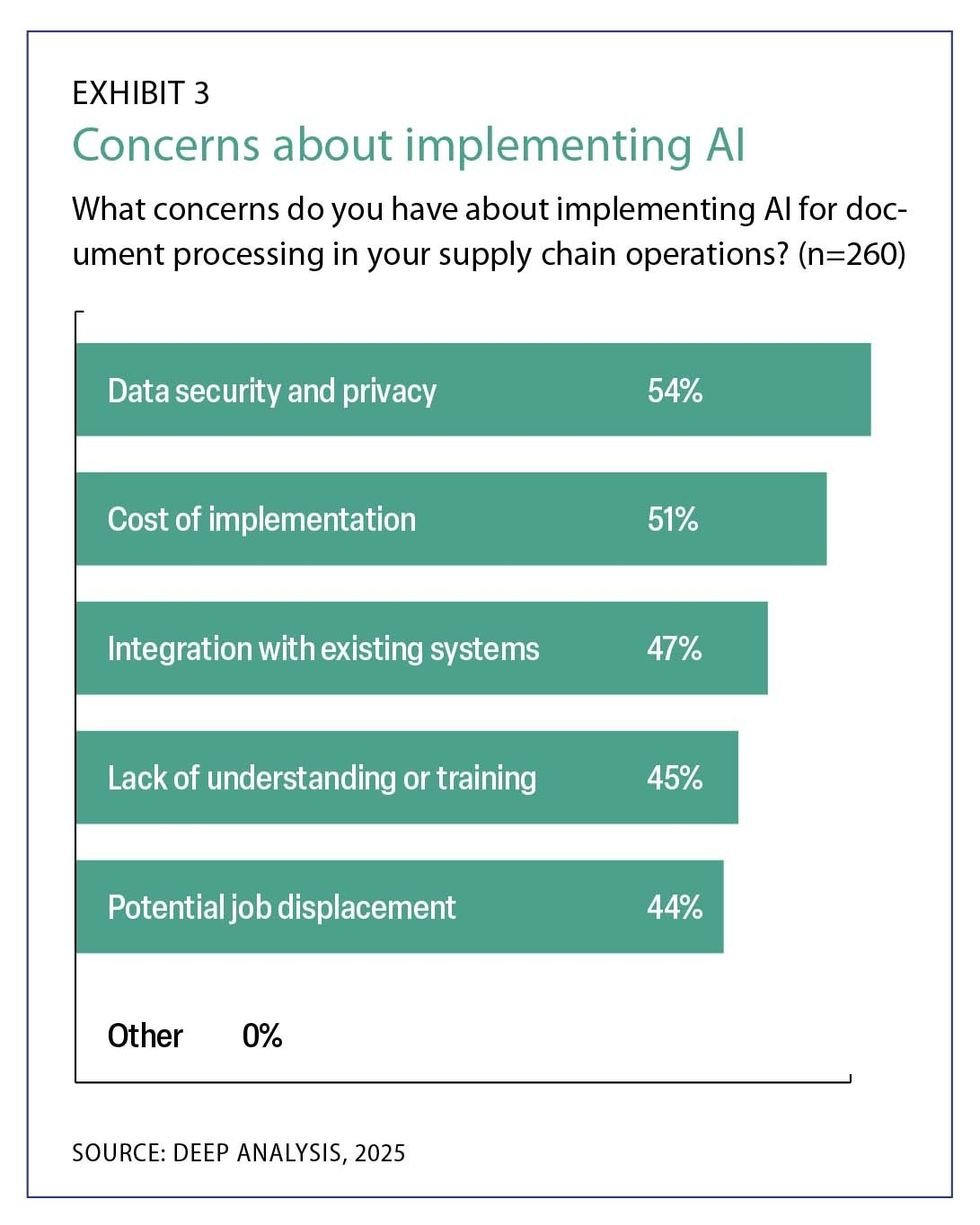

Despite the clear potential of AI, significant barriers to adoption remain. The survey respondents reported several concerns about implementing AI for back-office processes (see Exhibit 3). The most common concerns include:

1. Data security and privacy (54%): Transportation and logistics companies handle a large volume of sensitive data, including customer information, shipment details, and payment records. Ensuring robust security protocols and compliance with privacy regulations is critical for any AI implementation.

2. Cost of implementation (51%): AI technologies require considerable upfront investment in both hardware and software, and many smaller logistics firms or those with tight margins may find it difficult to justify this expense.

3. Integration with existing systems (47%): Many logistics companies still rely on traditional TMS and ERP systems that were not built with AI in mind, requiring substantial and extensive investment in infrastructure upgrades.

ESSENTIAL STEPS

No matter how powerful a technology is, its effectiveness in the real world of business is only as good as the planning and execution of a transformation project. As companies look to implement AI, they must make sure to take essential steps such as standardizing data formats, investing in workforce training, and fostering industrywide collaboration. The report concludes with several recommendations for companies looking to adopt AI and automation in their back-office operations, including:

1. Invest in AI training: Providing employees with training on AI tools and systems will help bridge the knowledge gap and increase adoption rates.

2. Focus on incremental implementation: Starting with pilot projects allows companies to assess the technology’s return on investment (ROI) and build confidence in AI technologies before large-scale deployment.

3. Develop industry standards: Collaborate with industry groups to establish standardized document formats and processing protocols, reducing inefficiencies and errors.

4. Prioritize integration: Select AI solutions that integrate seamlessly with existing systems, minimizing disruption during the transition.

5. Monitor emerging technologies: Stay informed about advancements in AI, such as intelligent document processing (IDP) and robotic process automation (RPA), to remain competitive.

THE TIME IS NOW

The transportation and logistics sector is at a pivotal moment, with significant opportunities to leverage AI and automation to address long-standing inefficiencies in back-office operations. While challenges such as integration, cost, and training remain, the industry is moving steadily toward broader adoption of digital and AI-based solutions. By addressing these barriers and focusing on incremental, strategic implementation, companies can unlock the full potential of automation and AI, driving efficiency and competitiveness in an increasingly complex and indeed volatile market.

Some may be understandably skeptical of AI’s ability to truly transform back-office operations, particularly given past failures to digitize paper-based processes. Certainly, no technology is perfect, and its effectiveness is dependent on how well the organization plans and executes its implementation. However, it’s important to note that huge advances have been made in the ability of AI to read, understand, and process document-based processes. As a result, AI has the potential to make relatively light work of anything from invoices to bills of lading, providing accuracy levels typically far higher than were a human to do the work manually.

For supply chain professionals, the message is clear: The future of T&L lies in embracing digital transformation, investing in AI, and fostering collaboration across the industry. The time to act is now.

About the research

In 2024, the document automation company Hyperscience and the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) partnered with the research and advisory firm Deep Analysis on a research project exploring the current state of back-office processes in transportation and logistics, and the potential impact of AI. The report, “Market Momentum Index: AI Readiness in Transportation and Logistics Back-Office Operations,” is based on survey results from senior-level managers and executives from 300 enterprises located in the United States. All of these organizations have annual revenues greater than $10 million and more than 1,000 employees. The survey was conducted in November and December of 2024. The full 21-page report can be downloaded for free at https://explore.hyperscience.ai/report-ai-readiness-in-transportation-logistics.

AI Insights

Anthropic to pay authors $1.5 billion in settlement over chatbot training material : NPR

Thriller novelist Andrea Bartz is photographed in her home Thursday in the Brooklyn borough of New York City.

Richard Drew/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Richard Drew/AP

NEW YORK — Artificial intelligence company Anthropic has agreed to pay $1.5 billion to settle a class-action lawsuit by book authors who say the company took pirated copies of their works to train its chatbot.

The landmark settlement, if approved by a judge as soon as Monday, could mark a turning point in legal battles between AI companies and the writers, visual artists and other creative professionals who accuse them of copyright infringement.

The company has agreed to pay authors about $3,000 for each of an estimated 500,000 books covered by the settlement.

“As best as we can tell, it’s the largest copyright recovery ever,” said Justin Nelson, a lawyer for the authors. “It is the first of its kind in the AI era.”

A trio of authors — thriller novelist Andrea Bartz and nonfiction writers Charles Graeber and Kirk Wallace Johnson — sued last year and now represent a broader group of writers and publishers whose books Anthropic downloaded to train its chatbot Claude.

The Anthropic website and mobile phone app are shown in this photo in New York on July 5, 2024.

Richard Drew/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Richard Drew/AP

A federal judge dealt the case a mixed ruling in June, finding that training AI chatbots on copyrighted books wasn’t illegal but that Anthropic wrongfully acquired millions of books through pirate websites.

If Anthropic had not settled, experts say losing the case after a scheduled December trial could have cost the San Francisco-based company even more money.

“We were looking at a strong possibility of multiple billions of dollars, enough to potentially cripple or even put Anthropic out of business,” said William Long, a legal analyst for Wolters Kluwer.

U.S. District Judge William Alsup of San Francisco has scheduled a Monday hearing to review the settlement terms.

Anthropic said in a statement Friday that the settlement, if approved, “will resolve the plaintiffs’ remaining legacy claims.”

“We remain committed to developing safe AI systems that help people and organizations extend their capabilities, advance scientific discovery, and solve complex problems,” said Aparna Sridhar, the company’s deputy general counsel.

As part of the settlement, the company has also agreed to destroy the original book files it downloaded.

Books are known to be important sources of data — in essence, billions of words carefully strung together — that are needed to build the AI large language models behind chatbots like Anthropic’s Claude and its chief rival, OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

Alsup’s June ruling found that Anthropic had downloaded more than 7 million digitized books that it “knew had been pirated.” It started with nearly 200,000 from an online library called Books3, assembled by AI researchers outside of OpenAI to match the vast collections on which ChatGPT was trained.

Debut thriller novel The Lost Night by Bartz, a lead plaintiff in the case, was among those found in the Books3 dataset.

Anthropic later took at least 5 million copies from the pirate website Library Genesis, or LibGen, and at least 2 million copies from the Pirate Library Mirror, Alsup wrote.

The Authors Guild told its thousands of members last month that it expected “damages will be minimally $750 per work and could be much higher” if Anthropic was found at trial to have willfully infringed their copyrights. The settlement’s higher award — approximately $3,000 per work — likely reflects a smaller pool of affected books, after taking out duplicates and those without copyright.

On Friday, Mary Rasenberger, CEO of the Authors Guild, called the settlement “an excellent result for authors, publishers, and rightsholders generally, sending a strong message to the AI industry that there are serious consequences when they pirate authors’ works to train their AI, robbing those least able to afford it.”

The Danish Rights Alliance, which successfully fought to take down one of those shadow libraries, said Friday that the settlement would be of little help to European writers and publishers whose works aren’t registered with the U.S. Copyright Office.

“On the one hand, it’s comforting to see that compiling AI training datasets by downloading millions of books from known illegal file-sharing sites comes at a price,” said Thomas Heldrup, the group’s head of content protection and enforcement.

On the other hand, Heldrup said it fits a tech industry playbook to grow a business first and later pay a relatively small fine, compared to the size of the business, for breaking the rules.

“It is my understanding that these companies see a settlement like the Anthropic one as a price of conducting business in a fiercely competitive space,” Heldrup said.

The privately held Anthropic, founded by ex-OpenAI leaders in 2021, said Tuesday that it had raised another $13 billion in investments, putting its value at $183 billion.

Anthropic also said it expects to make $5 billion in sales this year, but, like OpenAI and many other AI startups, it has never reported making a profit, relying instead on investors to back the high costs of developing AI technology for the expectation of future payoffs.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms4 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics