Education

The move from principal to district leader was fraught–here’s what I missed the most

This story was originally published by Chalkbeat. Sign up for their newsletters at ckbe.at/newsletters.

I didn’t expect to grieve.

I knew taking a central office role meant trading the school building for a district badge. I knew the days would be filled with policy, meetings, and personnel issues. What I didn’t know was how much I would miss morning announcements, front office chatter, and the small but sacred chaos of classroom life.

When I accepted my central office role at Knox County Schools nearly three years ago, I heard words of congratulations and encouragement, and a lot of “You’ll be great at this.” What I didn’t hear was, “You’re going to miss the cafeteria noise” or “You’ll feel phantom pain for your walkie and reach for it like it’s still there.” No one warned me I’d find myself lingering too long during school visits, trying to feel like I still belong.

What I lost wasn’t just proximity; it was identity.

As a principal, I was part of everything. Students shouted greetings across the parking lot. Parents stopped me in the grocery store to ask about bus routes or share weekend news. Teachers popped into my office with questions or just to drop off a piece of cake from the lounge. I wasn’t above the work. I was in it. I was woven into the messy, beautiful rhythm of a school day.

Shifting to the central office changed not just the pace of my day, but the feel of the work. The space was quieter, the communication more deliberate. There are no morning announcements. No car rider line and morning high-fives from kids. No spontaneous TikTok dances during class change. I moved from the rhythm of a living, breathing school to a place where school leadership feels more technical, more filtered, and more removed.

The relationships changed, too. As a principal, you’re not just part of a team; you’re a part of a family. You laugh together, carry each other’s burdens, and share both the stress and the wins. Move into a district role, and you’re now “from downtown,” even if your heart still lives on campus. You walk into buildings with a badge that means something different, and the conversations shift just enough for you to notice.

None of this means the central office work doesn’t matter. It does. Or that I don’t love it. I do. Central office work gives me a systems-level view of how our schools function. I find purpose in improving not just individual outcomes, but the structures that guide them.

Still, the change in relational gravity caught me off guard. And once the initial disorientation passed, it left me with a deeper concern: How will I stay connected to how the work is actually experienced and carried out in schools if I’m no longer living in it each day?

At first, I told myself it was just a learning curve, that it would pass, that I’d find new rhythms soon enough. And I did — but not before realizing that central office leadership requires a different kind of muscle. One I hadn’t needed before.

As a principal, I lived in fast feedback loops. I saw the effects of my decisions by lunchtime. I knew which teachers were having a hard week, which student needed extra eyes, which parent was about to call. Even hard conversations came with a certain clarity because I was close to the context and knew the culture I wanted to build.

At the district level, the impact is broader but harder to track. The wins take longer to see. The feedback is quieter.

I had to become more intentional about noticing what I could no longer see. That meant listening differently during school visits, paying closer attention to what leaders were navigating, and asking better questions. Not just about what was happening, but what it was costing them to make it happen.

One of the advantages of working at a systems level is being able to recognize patterns across multiple settings. They can reveal root causes that individual concerns might never expose. That clarity opens the door to more aligned, lasting support.

I began thinking less about whether expectations were clear and more about whether they were sustainable. My role was not to direct the work but to support the people carrying it out.

These changes didn’t come naturally. They came because I didn’t want to become a leader who made good decisions in theory but stayed out of touch in practice. I didn’t want to lead by spreadsheet, even though color-coded tabs bring me great joy. I wanted to lead by understanding.

Eventually, I began to see that even though I was no longer in the thick of the school day, I could still choose to stay connected — to show up, to ask real questions, to build trust not just through policy, but through presence.

The classroom educators and school leaders I supported didn’t need someone who had knowledge of what it was like to be a teacher or principal. They needed someone who remembered what it felt like to be one. Someone who hadn’t forgotten the rush of the morning bell or the weight of a tough parent meeting or the impossible feeling of juggling school culture, teacher evaluations, instructional priorities, and a leaky roof all before noon.

I think back often to my first year in central office. The silence. The absence of bells and kids and chaos. The invisible weight of missing something no one warned me I would lose. I remember walking through a school one afternoon and instinctively reaching for my walkie talkie. It wasn’t there. Of course it wasn’t there. But the reflex reminded me of something important: I still wanted to be tuned in.

Leadership doesn’t have to grow lonelier as it grows broader. But staying connected takes intention. It takes habits, not just memories.

I didn’t expect to grieve. But I’m grateful I did. Because grief has a way of reminding you what still deserves your presence.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.

For more news on district management, visit eSN’s Educational Leadership hub.

Education

A largely invisible role of international students: Fueling the innovation economy

PITTSBURGH — Saisri Akondi had already started a company in her native India when she came to Carnegie Mellon University to get a master’s degree in biomedical engineering, business and design.

Before she graduated, she had co-founded another: D.Sole, for which Akondi, who is 28, used the skills she’d learned to create a high-tech insole that can help detect foot complications from diabetes, which results in 6.8 million amputations a year.

D.Sole is among technology companies in Pittsburgh that collectively employ a quarter of the local workforce at wages much higher than those in the city’s traditional steel and other metals industries. That’s according to the business development nonprofit the Pittsburgh Technology Council, which says these companies pay out an annual $27.5 billion in salaries alone.

A “significant portion” of Pittsburgh’s transformation into a tech hub has been driven by international students like Akondi, said Sean Luther, head of InnovatePGH, a coalition of civic groups and government agencies promoting innovation businesses.

“Next Happens Here,” reads the sign above the entrance to the co-working space where Luther works and technology companies are incubated, in an area near Carnegie Mellon and the University of Pittsburgh dubbed the Pittsburgh Innovation District. The neighborhood is filled with people of various ethnicities speaking a variety of languages over lunch and coffee.

What might happen next to the international students and graduates who have helped fuel this tech economy has become an anxiety-inducing subject of those conversations, as the second presidential administration of Donald Trump brings visa crackdowns, funding cuts and other attacks on higher education — including here, in a state that voted for Trump.

Related: Interested in innovations in higher education? Subscribe to our free biweekly higher education newsletter.

Inside the bubble of the universities and the tech sector, “there’s so much support you get,” Akondi observed, in a gleaming conference room at Carnegie Mellon. “But there still is a part of the population that asks, ‘What are you doing here?’ ”

Much of the ongoing conversation about international students has focused on undergraduates and their importance to university revenues and enrollment. Many of these students — especially in graduate schools — fill a less visible role in the economy, however. They conduct research that can lead to commercial applications, have skills employers need and start a surprising number of their own companies in the United States.

“The high-tech engineering and computer science activities that are central to regional economic development today are hugely dependent on these students,” said Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who studies technology and innovation. “If you go into a lab, it will be full of non-American people doing the crucial research work that leads to intellectual property, technology partnerships and startups.”

Some 143 U.S. companies valued at $1 billion or more were started by people who came to the country as international students, according to the National Foundation for American Policy, a nonprofit that conducts research on immigration and trade. These companies have an average of 860 employees each and include SpaceX, founded by Elon Musk, who was born in South Africa and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania.

Whether or not they invent new products or found businesses of their own, international graduates are “a vital source” of workers for U.S.-based tech companies, the National Science Foundation reported last year in an annual survey on the state of American science and engineering.

It’s supply and demand, said Dave Mawhinney, a professor of entrepreneurship at Carnegie Mellon and founding executive director of its Swartz Center for Entrepreneurship, which helps many of that school’s students do research that can lead to products and startups. “And the demand for people with those skills exceeds the supply.”

States with the most international students

California: 140,858

New York: 135,813

Texas: 89,546

Massachusetts: 82,306

Illinois: 62,299

Pennsylvania: 50,514

Florida: 44,767

Source: NAFSA: Association of International Educators. Figures are from the 2023-24 academic year, the most recent available.

Related: So much for saving the planet. Climate careers, and many others, evaporate for class of 2025

That’s in part because comparatively few Americans are going into fields including science, technology, engineering and math. Even before the pandemic disrupted their educations, only 20 percent of college-bound American high school students were prepared for college-level courses in these subjects. U.S. students scored lower in math than their counterparts in 21 of the 37 participating nations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development on an international assessment test in 2022, the most recent year for which the outcomes are available.

One result is that international students make up more than a third of master’s and doctoral degree recipients in science and engineering at American universities. Two-thirds of U.S. university graduate students and more than half of workers in AI and AI-related fields are foreign born, according to Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

“A real point of strength, and a reason our robotics companies especially have been able to grow their head counts, is because of those non-native-born workers,” said Luther, in Pittsburgh. “Those companies are here specifically because of that talent.”

International students are more than just contributors to this city’s success in tech. “They have been drivers” of it, Mawhinney said, in his workspace overlooking the studio where the iconic children’s television program “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” was taped.

“Every year, 3,000 of the smartest people in the world come here, and a large proportion of those are international,” he said of Carnegie Mellon’s graduate students. “Some of them go into the research laboratories and work on new ideas, and some come having ideas already. You have fantastic students who are here to help you build your company or to be entrepreneurs themselves.”

Boosters of the city’s tech-driven turnaround say what’s been happening in Pittsburgh is largely unappreciated elsewhere. It followed the effective collapse of the steel industry in the 1980s, when unemployment hit 18 percent.

In 2006, Google opened a small office at Carnegie Mellon to take advantage of the faculty and student expertise in computer science and other fields there and at neighboring higher education institutions; the company later moved to a nearby former Nabisco factory and expanded its Pittsburgh workforce to 800 employees. Apple, software and AI giant SAP and other tech firms followed.

“It was the talent that brought them here, and so much of that talent is international,” said Audrey Russo, CEO of the Pittsburgh Technology Council.

Sixty-one percent of the master’s and doctoral students at Carnegie Mellon come from abroad, according to the university. So do 23 percent of those at Pitt, an analysis of federal data shows.

Related: International students are rethinking coming to the US. That’s a problem for colleges

The city has become a world center for self-driving car technology. Uber opened an advanced research center here. The autonomous vehicle company Motional — a joint venture between Hyundai and the auto parts supplier Aptiv — moved in. So did the Ford- and Volkswagen-backed Argo AI, which eventually dissolved, but whose founders went on to create the Pittsburgh-based self-driving truck developer Stack AV. The Ford subsidiary Latitude AI and the autonomous flight company Near Earth Autonomy also are headquartered in Pittsburgh.

Among other tech firms with homes here: Duolingo, which has 830 employees and is worth an estimated $22 billion. It was co-founded by a professor at Carnegie Mellon and a graduate of the university who both came to the United States as international students, from Guatemala and Switzerland, respectively.

InnovatePGH tracks 654 startups that are smaller than those big conglomerates but together employ an estimated 25,000 workers. Unemployment in Pittsburgh (3.5 percent in April) is below the national average (3.9 percent). Now Pitt and others are developing Hazelwood Green, which includes a former steel mill that closed in 1999, into a new district housing life sciences, robotics and other technology companies.

In a series of webinars about starting businesses, offered jointly to students at Pitt and Carnegie Mellon, the most popular installment is about how to found a startup on a student visa, said Rhonda Schuldt, director of Pitt’s Big Idea Center, in a storefront on Forbes Avenue in the Innovation District.

Some international undergraduates continue into graduate school or take jobs with companies that sponsor them so they can keep working on their ideas, Schuldt said.

“They want to stay in Pittsburgh and build businesses here,” she said.

There are clear worries that this momentum could come to a halt if the supply of international students continues a slowdown that began even before the new Trump term, thanks to visa processing delays and competition from other countries.

The number of international graduate students dropped in the fall by 2 percent, before the presidential election, according to the Institute of International Education. Further declines are expected following the government’s pause on student visa interviews, publicity surrounding visa revocations and arrests and cuts to federal research funding.

It’s too early to know what will happen this fall. But D. Sole co-founder Saisri Akondi has heard from friends who planned to come to the United States that they can’t get visas. “Most of these students wanted to start companies,” she said.

“I would be lying if I said nothing has changed,” said Akondi, who has been accepted into a master’s degree program in business administration at the Stanford University Graduate School of Business under her existing student visa, though she said her company will stay in Pittsburgh. “The fear has increased.”

This could affect whether tech companies continue to come to Pittsburgh, said Russo, at least unless and until more Americans are better prepared for and recruited into tech-related graduate programs. That’s something universities have not yet begun to do, since the unanticipated threat to their international students erupted only in March, and that would likely take years.

“Who’s going to do the research? Who’s going to be in these teams?” asked Russo. “We’re hurting ourselves deeply.”

The impact could transcend the research and development ecosystem. “I think we’ll see almost immediate ramifications in Pittsburgh in terms of higher-skilled, higher-wage companies hiring here,” said Sean Luther, at InnovatePGH. “And that affects the grocery shops, the barbershops, the real estate.”

There are other, more nuanced impacts.

“Whether we like it or not, it’s a global world. It’s a global economy. The problems that these students want to solve are global problems,” Schuldt said. “And one of the things that is really important in solving the world’s problems is to have a robust mix of countries, of cultures — that opportunity to learn how others see the world. That is one of the most valuable things students tell us they get here.”

Pittsburgh is a prime example of a place whose economy is vulnerable to a decline in the number of international students, said Brookings’ Muro. But it’s not unique.

“These scholars become entrepreneurs. They’re adding to the U.S. economy new ideas and new companies,” he said. Without them, “the economy would be smaller. Research wouldn’t get done. Journal articles wouldn’t be written. Patents wouldn’t be filed. Fewer startups would occur.”

The United States, said Muro, “has cleaned up by being the absolute central place for this. The system has been incredibly beneficial to the United States. The hottest technologies are inordinately reliant on these excellent minds from around the world. And their being here is critical to American leadership.”

Contact writer Jon Marcus at 212-678-7556, jmarcus@hechingerreport.org or jpm.82 on Signal.

This story about international students was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for our higher education newsletter. Listen to our higher education podcast.

Education

First week ‘critical’ to avoid children missing school later, parents told

Hazel ShearingEducation correspondent

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPupils in England who missed school during the first week back in September 2024 were more likely to miss large parts during the rest of the year, figures suggest.

More than half (57%) of pupils who were partially absent in week one became “persistently absent” – missing at least 10% of school, according to government data first seen by the BBC.

By contrast, of pupils who fully attended the first week, 14% became persistently absent.

Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson said schools and parents should “double down” to get children in at the start of the 2025 term, which is this week for most English schools.

A head teachers’ union said more support was needed “outside of the school gates” to boost attendance.

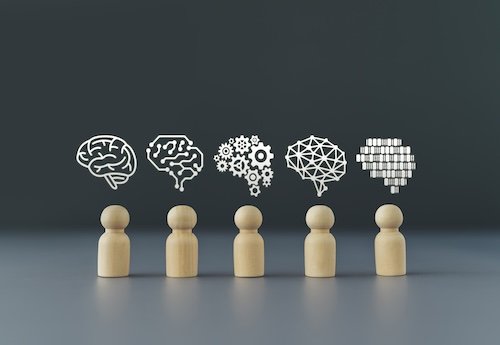

Schools have always grappled with attendance issues, but they became much worse after the pandemic in 2020 and schools closed to most pupils during national lockdowns.

Attendance has improved since, but it remains a bigger problem than before Covid.

Overall, about 18% of pupils were persistently absent in the 2024-25 school year, down from a peak of 23% in 2021-22 but higher than the pre-Covid levels of about 11%.

The Department for Education (DfE) said the data from the first week of the 2024-25 school year showed the start of term was “critical” for tackling persistent absence.

Karl Stewart, head teacher at Shaftesbury Junior School in Leicester, said his school’s attendance rates were higher than average and but there was a “definite dip” in the two years after Covid.

“I get why. Some of that wasn’t necessarily parents not wanting to send them in. It was because either they had got Covid or other things, they were saying, ‘We’ll just keep them off now to be sure’,” he said.

The school has incentives like awards and class competitions to keep absence rates down, and Mr Stewart said attendance had more or less returned to pre-Covid levels.

“When we have the children in every day the results are just better,” he said.

“If you’re here, that gives you more time for your teacher to notice you, for us to see all that good behaviour [and] that really hard work – and that’s what we want.”

But, like lots of schools, he said some parents still took their children on unauthorised term-time holidays to make the most of cheaper costs.

Others, he said, have taken children for medical treatments overseas to avoid NHS waiting lists.

The education secretary said that while attendance improved last year, absence levels “remain critically high, putting at risk the life chances of a whole generation of young people”.

“Every day of school missed is a day stolen from a child’s future,” Phillipson said.

“As the new term kicks off, we need schools and parents to double down on the energy, the drive and the relentlessness that’s already boosted the life chances of millions of children, to do the same for millions more.”

The DfE said 800 schools were set to be supported by regional school improvement teams – through attendance and behaviour hubs.

These hubs are made up of 90 exemplary schools which will offer support to improve struggling schools through training sessions, events and open days.

It said it had appointed the first 21 schools that will lead the programme.

However, Pepe Di’Iasio, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said attendance hubs were not a “silver bullet” and a more “strategic approach” was needed.

“I think the government has worked really hard to improve attendance and it continues to be a priority for them, but there’s certainly more to do,” he told the BBC.

“So many of the challenges that [school leaders] are facing come from beyond the school gates – children suffering with high levels of anxiety, issues around mental health.”

He said school leaders wanted quicker access to support for those pupils and specialist staff in schools, but pupils also needed “great role models” in the community through youth clubs and volunteer groups.

The Conservatives said Labour’s Schools Bill had dismantled a “system that has driven up standards for decades”.

Shadow education secretary Laura Trott said: “Behaviour and attendance are two of the biggest challenges facing schools and it’s about time the government acted.”

She added: “There must be clear consequences for poor behaviour not just to protect the pupils trying to learn, but to recognise when mainstream education isn’t the right setting for those causing disruption.”

Additional reporting by Nathan Standley

Education

AI in the classrooms: How Bangladeshi schools are adapting to a new digital era

The recent explosion of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has pervaded numerous industries, going from a futuristic concept to an everyday reality. However, the impact of AI on schooling has been exceptionally staggering.

From helping students complete assignments to reshaping the way teachers think about homework and exams, AI is beginning to redefine education all over the world.

Bangladesh is no different.

Artificial Intelligence isn’t just coming to Bangladeshi classrooms—it’s already here. While its promise of convenience and quick solutions is quite alluring to students, the ever-growing presence of AI in schools has raised difficult questions: is learning actually taking place anymore or is it being replaced by answers generated not from thought, but from machines?

In schools across Bangladesh, AI tools like ChatGPT have quietly revolutionised how students complete their homework, how teachers prepare lessons, and how institutions rethink education altogether.

Is it a blessing or a bane?

Students have quickly adapted to using advanced AI chatbots like ChatGPT, making AI an unavoidable and integral part of academic life. From essays to homework, students are increasingly finding ways to rely on AI not just to work faster, but to sidestep studying altogether.

Many schools and educators have now been forced to accept that resisting AI is no longer an option. Schools must adapt to the new reality or risk becoming redundant.

Yafa Rahman, Vice Principal and Senior Business Studies Teacher of Adroit International School, told The Business Standard, “Talks about integrating AI in the school curriculum is a global concern, and my school has had meetings with Pearson Education on how to do that in the best possible manner as well as train teachers to use AI in a beneficial way while being able to spot unethical AI use. This is an ongoing discussion, and we will see many changes soon.”

Yafa explained that her school also employs AI tools to structure assignments and class content. Rather than banning AI altogether, she believes in channelling students’ fascination with technology into meaningful learning. “Students rely on technology so much that if we incorporate any technology into the learning process, students instantly become more interested,” she said.

Rethinking the curriculum

The convenience of AI comes with a heavy cost. Teachers are reporting a surge in AI-generated assignments. Entire essays, reports, and even personal reflections are being turned in with no human touch. And it’s getting harder to spot the difference.

Educators have responded by rethinking the very structure of education in the country. Oral assessments, in-class essays, and presentations have become increasingly common, as schools seek to test students’ independent thinking rather than their ability to reproduce AI-generated answers.

“For assignments meant to show knowledge and understanding, I’ve returned to using pencil and paper to prevent AI use. For reflective assignments, I encourage students to use AI but remind them to think critically. You do not always have to agree with what AI generated, and key facts and figures must be checked with reliable sources,” said Olivier Gautheron, a Science Teacher at International School Dhaka (ISD) who has earned the “AI Essentials for Educators” certification from Edtech Teachers in the US.

This hybrid approach reflects a wider consensus among educators that AI should not be ignored but incorporated responsibly, encouraging students to refine their critical faculties alongside their digital literacy.

It’s no longer just about stopping AI from being used. It’s about guiding how it’s used.

AI detection

Detecting AI-generated work isn’t straightforward. In universities, plagiarism software and AI detectors are standard. But in schools, teachers often rely on their personal knowledge of each student’s writing style and capability, using their instincts to identify when a student’s writing does not look like their own.

But Gautheron warns against over-reliance on intuition, preferring restraint over wrongful accusations.

“I believe it all comes down to knowing your students and their abilities,” he said. “There’s a high chance of mistakenly identifying student work as AI-generated when it’s not.”

He recalled an incident when he suspected a student of using AI, only to learn that the child had simply used software to improve grammar without altering the ideas. “This is perfectly acceptable, as the purpose of the assignment was for students to generate their own ideas,” he added.

He believes the solution lies not in advanced software but in dialogue. “Although software exists to detect AI, there are other softwares to make them undetectable. I believe that the best way to detect inappropriate use of AI is asking your students directly. If I feel that a student’s work quality is very different from previous tasks, simply asking them to clarify a few ideas of their work is enough.”

For resource-constrained schools, this approach is also pragmatic, since not every institution can afford detection software.

AI for teachers

Just like students, teachers are also increasingly turning to AI for lesson planning and content creation

Emran Taher, Cambridge examiner and senior English instructor at Mastermind School, sees AI as a game-changer.

“It is not just the students who use AI. Teachers and schools are using it too. I can keep my syllabus up-to-date and incorporate more relevant topics and examples instead of just relying on textbooks. This helps grab students’ interest while reducing issues like bunking classes.”

He also uses AI for personalised instruction. By feeding student data—age, class level, strengths, and weaknesses—into AI tools, he receives tailored recommendations that help him address individual needs. “There are no bad students, only bad teachers,” he said.

Striking the right balance

AI’s presence in schools reveals a tension: the same tool that can personalise learning and spark creativity can also be used to bypass real thinking. This balancing act between embracing innovation and preserving the essence of education appears to be the defining challenge of AI use.

However, there is no turning back. AI is already embedded in how schools operate. What matters now is how educators choose to respond. As Bangladeshi schools navigate this shift, teacher training, investment in digital infrastructure, and the development of ethical guidelines will all be crucial.

Some see AI as a threat to academic honesty. Others see it as a catalyst for overdue change in the old, rigid education system. But everyone realises that the role of teachers must evolve to address the new digital landscape.

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences3 months ago

Events & Conferences3 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoAstrophel Aerospace Raises ₹6.84 Crore to Build Reusable Launch Vehicle