Education

Stirchley school closed on first day of term after pipes stolen

A primary school has not reopened for the new term after thieves stole pipes leaving the site without water.

Davie Clifford, head teacher of Stirchley Primary School in Birmingham, said staff were working closely with engineers, who were on site, to restore the supply as quickly as possible.

He said the school, off Pershore Road, had been left without running water after pipework was stolen during a break-in at an unoccupied local constituency office, which affected supplies to the school.

Kitchens, toilets and access to drinking water were affected and staff had no option but to close the school, he said. He did not say when it might reopen.

He added: “I know this causes disruption for our families and, most importantly, for the children’s learning, and I am truly sorry for the inconvenience.”

The head teacher said the school would continue to keep parents fully updated.

The school calendar said children were expected to return for the start of the new school year on Tuesday.

Education

Summer’s ending – and the delusion that a new me might be possible is back | Emma Brockes

Every year at this time, I think of a quote from the Bible, but which I know from Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit by Jeanette Winterson, in which seven-year-old Jeanette stitches a needlepoint sampler decorated withthe inscription: “The summer is ended and we are not yet saved.” We are not yet saved: no, not in this house, where I experience the back-to-school week in September far more urgently than New Year’s Day as the time of year for a behavioural reset. New school year, new me, new cast-iron conviction I can put the rocky road on the top shelf after I’ve used it in my girls’ packed lunches and not get it down until tomorrow.

This is the first and most pressing item on the list: diet. Ten days out from Iberico ham night at the all-inclusive buffet in Spain, and I’m still more jamón than woman. It wouldn’t have mattered 10 years ago. But you can’t stuff your face with cold cuts and eat cake for breakfast, lunch and dinner (what? I’d paid for it, am I not going to eat it?) in middle age without triggering intense thoughts of death. And so this morning, after the drop-off: a return to the thrilling self-denial of two slices of misery bread from the health food store (fibre content: dysentery level). And a resolve to settle on a stable position re chia seeds, once and for all.

Also this morning, a cold, critical eye on the house after six weeks of people being in it all day. Pressing concerns include working out how to empty the chamber in the handheld vacuum and moving the leaning pile of clothes by the door to a charity shop – not a risk-free task, by the way. Shelter is so fancy these days that, like trying to offload books at Strand Books in New York, you suffer the very real possibility of being publicly shamed for having your sad castoffs from Primark rejected. On the pile, a single, bankable item – a Tory Burch shirt from back when I was trying to be someone else and a symbol of the occasional necessity of retiring one’s dreams. I will never get around to selling that shirt on Poshmark. I know that now.

It’s the same every year, this routine. Even though it’s modish these days to accept that “resolutions” pinned to a particular time of year don’t work, and we’re better off tweaking our general attitude year-round, I won’t give up this enjoyable period. I like a few weeks of stern reckoning. At the very least, the shortlived gusts of energy that come with them can be enough to clean the fridge and figure out where that clicking sound’s been coming from. Not the smoke alarm.

What remains curious is that the primary impetus during these periods tends towards small, trivial home- and diet-related chores, never anything big, like that massive deadline for the massive thing that’s on my mind and will somehow have to take care of itself. I know this is what we call displacement activity; the delusion that, through attention to the little things, we can get a better aerial view of What Is Really Going On. Which, in my case, for the past three months, has definitely been obscured by that pile of clothes by the door. It’s also the case that doing something physical but mindless, like wiping and scrubbing or folding and sorting, can put you in the slack-line mental state that allows bigger things to jump out. And I don’t mind a bit of displacement activity if it delivers the instant reward of striking one or two items off the endless mental to-do list.

So it goes on, Gatsby-style, year after year, as we thrust ourselves forward against waves of small obligations. Pay the cats more attention. The business pages: like, be more on top of them. Stop playing Block Blast on my phone. Have a strong word with myself about my coffee-and-snack spending. And the big one, obviously: stop putting rocky road in my children’s lunches and instead, batch bake bran muffins stuffed with secret avocado and – maybe? – chia seeds. It won’t last, but who cares? In the meantime, I’m happy to be soothed by the vague but heartfelt conviction that putting things in Tupperware will save me.

after newsletter promotion

Education

An invitation to dream together

Beyond grades, raising humans, not robots, thoughts from the founder of Veritas Learning Circle

The world our children are growing up in no longer resembles the one we were educated for. Traditional schooling models, built around standardized testing, rigid curricula, and a narrow definition of success, are rapidly losing relevance. We are not preparing for the future. We are already in it. And the rules of the game must change.

For decades, academic grades and test scores have been treated as passports to opportunity. Yet research continues to show that academic success is not a reliable predictor of success in the real world. With the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI), the very notion of what constitutes meaningful work and learning is shifting beneath our feet. The question is no longer, “What jobs will exist?” but rather, “What kinds of humans will thrive?”

Beyond teachers and textbooks

In countries like Pakistan, concerns about teacher quality have long haunted education. But with the advent of AI, these barriers can be reimagined. A child in Karachi could have access to the same caliber of resources as one in Helsinki or Singapore. Knowledge has been democratized. What will matter now is not what students learn, but how they learn and who they become in the process.

This also means the teacher’s role must fundamentally shift. Teachers are no longer just transmitters of knowledge; they must become facilitators and co-learners, guiding students as they design their own paths and collaborate with technology.

This is why the school of the future must evolve into something far greater than a delivery system for content. It must become a community: a place where students, teachers, and parents co-create learning journeys, where technology enhances but does not replace human connection, and where every child is guided to uncover their unique gifts.

Honoring our humanness

We are not here to build robots who outperform machines. We are here to raise humans who can collaborate with machines while staying rooted in empathy, creativity, and self-awareness. The teacher’s role will no longer be to enforce discipline but to cultivate self-discipline, curiosity, and resilience in students.

In an era where children are drowning in screen time, schools must become sanctuaries of presence — spaces where conflict is resolved through dialogue, friendships are nurtured, and young people learn what it means to see and to be seen.

A call to collaborate

I do not claim to have all the answers. In truth, none of us can predict exactly where this journey with AI will take us. But I do know this: we cannot continue working in silos. The education sector has been segregated for too long. To reimagine the future, we need educators working hand-in-hand with scientists, technologists, financial leaders, artists, and parents.

This is not just a “nice to have.” It is our collective responsibility. Because it no longer takes just a village to raise a child — in the age of AI, it takes a global village.

I share these reflections not as definitive solutions but as an invitation. An invitation to dream together, to create together, and yes, even to rebel together against outdated systems that no longer serve our children. The future of education will not be written by one person, or one institution, but by a community of people who dare to believe that a better way is possible.

The time to begin is now. This is a call to the rebels, the dreamers, the scientists, and the artists — to come together and redefine the purpose of today’s schools.

Education

Nation’s Report Card at risk, researchers say

This story was reported by and originally published by APM Reports in connection with its podcast Sold a Story: How Teach Kids to Read Went So Wrong.

When voters elected Donald Trump in November, most people who worked at the U.S. Department of Education weren’t scared for their jobs. They had been through a Trump presidency before, and they hadn’t seen big changes in their department then. They saw their work as essential, mandated by law, nonpartisan and, as a result, insulated from politics.

Then, in early February, the Department of Government Efficiency showed up. Led at the time by billionaire CEO Elon Musk, and known by the cheeky acronym DOGE, it gutted the Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences, posting on X that the effort would ferret out “waste, fraud and abuse.”

A post from the Department of Government Efficiency.

When it was done, DOGE had cut approximately $900 million in research contracts and more than 90 percent of the institute’s workforce had been laid off. (The current value of the contracts was closer to $820 million, data compiled by APM Reports shows, and the actual savings to the government was substantially less, because in some cases large amounts of money had been spent already.)

Among staff cast aside were those who worked on the National Assessment of Educational Progress — also known as the Nation’s Report Card — which is one of the few federal education initiatives the Trump administration says it sees as valuable and wants to preserve.

The assessment is a series of tests administered nearly every year to a national sample of more than 10,000 students in grades 4, 8 and 12. The tests regularly measure what students across the country know in reading, math and other subjects. They allow the government to track how well America’s students are learning overall. Researchers can also combine the national data with the results of tests administered by states to draw comparisons between schools and districts in different states.

The assessment is “something we absolutely need to keep,” Education Secretary Linda McMahon said at an education and technology summit in San Diego earlier this year. “If we don’t, states can be a little manipulative with their own results and their own testing. I think it’s a way that we keep everybody honest.”

But researchers and former Department of Education employees say they worry that the test will become less and less reliable over time, because the deep cuts will cause its quality to slip — and some already see signs of trouble.

“The main indication is that there just aren’t the staff,” said Sean Reardon, a Stanford University professor who uses the testing data to research gaps in learning between students of different income levels.

All but one of the experts who make sure the questions in the assessment are fair and accurate — called psychometricians — have been laid off from the National Center for Education Statistics. These specialists play a key role in updating the test and making sure it accurately measures what students know.

“These are extremely sophisticated test assessments that required a team of researchers to make them as good as they are,” said Mark Seidenberg, a researcher known for his significant contributions to the science of reading. Seidenberg added that “a half-baked” assessment would undermine public confidence in the results, which he described as “essentially another way of killing” the assessment.

The Department of Education defended its management of the assessment in an email: “Every member of the team is working toward the same goal of maintaining NAEP’s gold-standard status,” it read in part.

The National Assessment Governing Board, which sets policies for the national test, said in a statement that it had temporarily assigned “five staff members who have appropriate technical expertise (in psychometrics, assessment operations, and statistics) and federal contract management experience” to work at the National Center for Education Statistics. No one from DOGE responded to a request for comment.

Harvard education professor Andrew Ho, a former member of the governing board, said the remaining staff are capable, but he’s concerned that there aren’t enough of them to prevent errors.

“In order to put a good product up, you need a certain number of person-hours, and a certain amount of continuity and experience doing exactly this kind of job, and that’s what we lost,” Ho said.

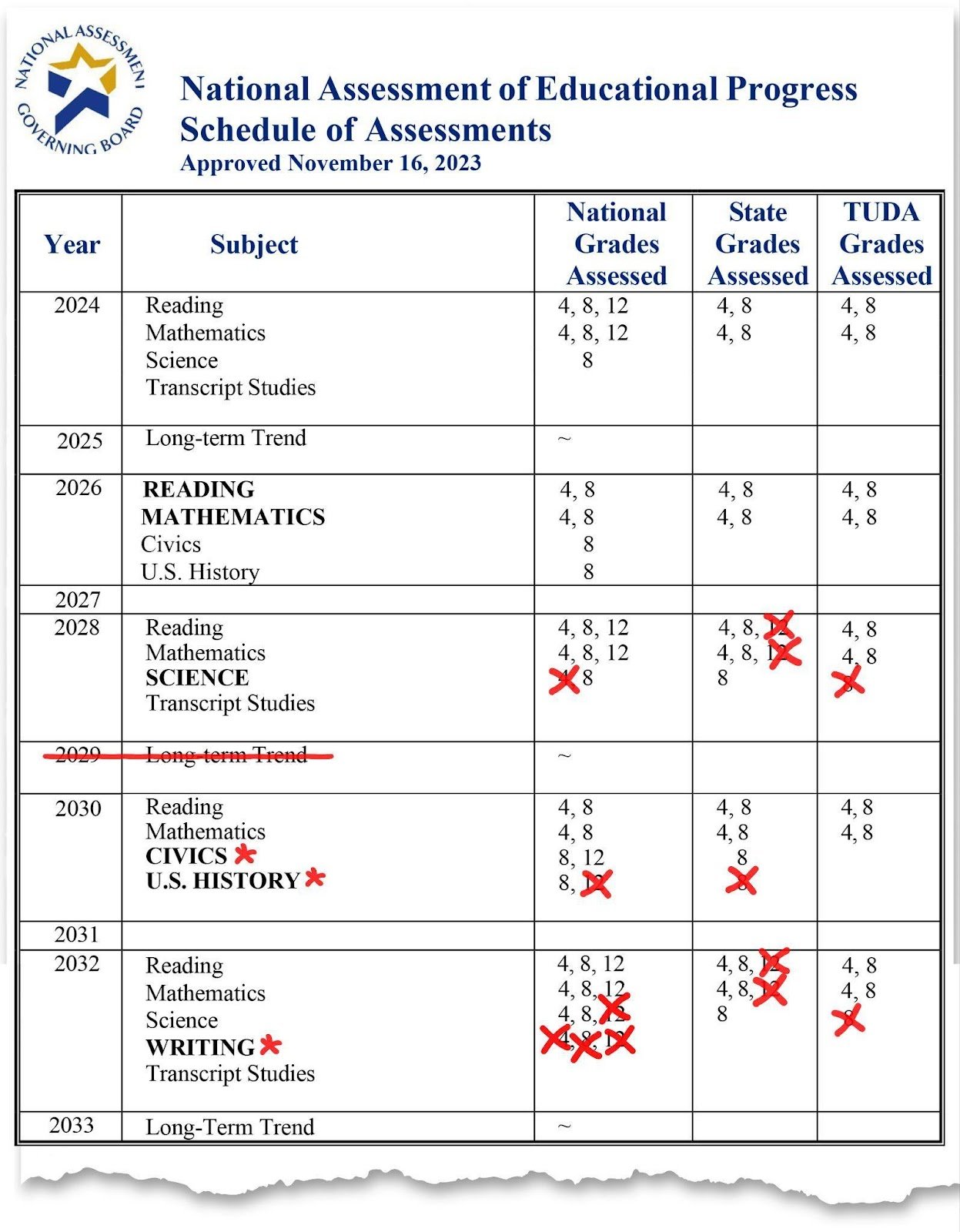

The Trump administration has already delayed the release of some testing data following the cutbacks. The Department of Education had previously planned to announce the results of the tests for 8th grade science, 12th grade math and 12th grade reading this summer; now that won’t happen until September. The board voted earlier this year to eliminate more than a dozen tests over the next seven years, including fourth grade science in 2028 and U.S. history for 12th graders in 2030. The governing board has also asked Congress to postpone the 2028 tests to 2029, citing a desire to avoid releasing test results in an election year.

“Today’s actions reflect what assessments the Governing Board believes are most valuable to stakeholders and can be best assessed by NAEP at this time, given the imperative for cost efficiencies,” board chair and former North Carolina Gov. Bev Perdue said earlier this year in a press release.

Recent estimates peg the annual cost to keep the national assessment running at about $190 million per year, a fraction of the department’s 2025 budget of approximately $195 billion.

Adam Gamoran, president of the William T. Grant Foundation, said multiple contracts with private firms — overseen by Department of Education staff with “substantial expertise” — are the backbone of the national test.

“You need a staff,” said Gamoran, who was nominated last year to lead the Institute of Education Sciences. He was never confirmed by the Senate. “The fact that NCES now only has three employees indicates that they can’t possibly implement NAEP at a high level of quality, because they lack the in-house expertise to oversee that work. So that is deeply troubling.”

The cutbacks were widespread — and far outside of what most former employees had expected under the new administration.

“I don’t think any of us imagined this in our worst nightmares,” said a former Education Department employee, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation by the Trump administration. “We weren’t concerned about the utter destruction of this national resource of data.”

“At what point does it break?” the former employee asked.

Related: Suddenly sacked

Every state has its own test for reading, math and other subjects. But state tests vary in difficulty and content, which makes it tricky to compare results in Minnesota to Mississippi or Montana.

“They’re totally different tests with different scales,” Reardon said. “So NAEP is the Rosetta stone that lets them all be connected.”

Reardon and his team at Stanford used statistical techniques to combine the federal assessment results with state test scores and other data sets to create the Educational Opportunity Project. The project, first released in 2016 and updated periodically in the years that followed, shows which schools and districts are getting the best results — especially for kids from poor families. Since the project’s release, Reardon said, the data has been downloaded 50,000 times and is used by researchers, teachers, parents, school boards and state education leaders to inform their decisions.

For instance, the U.S. military used the data to measure school quality when weighing base closures, and superintendents used it to find demographically similar but higher-performing districts to learn from, Reardon said.

If the quality of the data slips, those comparisons will be more difficult to make.

“My worry is we just have less-good information on which to base educational decisions at the district, state and school level,” Reardon said. “We would be in the position of trying to improve the education system with no information. Sort of like, ‘Well, let’s hope this works. We won’t know, but it sounds like a good idea.’”

Seidenberg, the reading researcher, said the national assessment “provided extraordinarily important, reliable information about how we’re doing in terms of teaching kids to read and how literacy is faring in the culture at large.”

Producing a test without keeping the quality up, Seidenberg said, “would be almost as bad as not collecting the data at all.”

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoAERDF highlights the latest PreK-12 discoveries and inventions