Education

St. Paul’s School in Pacific Beach begins pilot program for AI

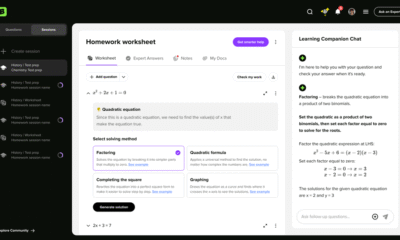

PACIFIC BEACH – St. Paul’s Lutheran Church and School of Pacific Beach is hosting a pilot program for new AI technology and learning, providing individualized instruction for students.

The school’s principal, Meredith Binnie, said use of new AI technology in the curriculum started with educators asking themselves, “What’s going to be the next big thing in education?… This past year, we did a lot of research about doing this (AI) program for the Lutheran School District Pacific Southwest District.”

Binnie, who has been St. Paul’s School’s principal since 2015, noted that the majority of students at St. Paul’s are in PB. But she added that pupils come from all over, including Point Loma, even East County.

“It’s also a great resource for teachers that are looking for more information,” Binnie added about the AI pilot. “The teachers will become more like guides and will be able to work with kids individually and in small groups.

“And it also opens up the time to do more collaborative critical-thinking projects in project-based learning. That’s exciting because if they (students) get all the basic skills out of the way, then they can do more higher-level thinking.”

Religious affiliation is not a prerequisite to be a St. Paul’s student. Graduates usually go on to attend the public high school they’re zoned for, typically in Mission Bay, La Jolla, and Clairemont.

The latest news from St. Paul’s includes the school’s garden celebrating its 10th anniversary and the church turning 82 years old and getting a new roof.

Binnie also counts the use of new AI technology instruction at the school as one of its latest milestones.

“One of the things that came out of these discussions is this new pilot program that a few of our schools are going to be doing. It is utilizing a new platform, giving students their personal AI tutor. They work at their own pace so they can excel, or they can get a little help, and it individualizes their instruction.

Binnie said the school has a Chromebook for every student. She added that the big question educators are asking themselves now is “How do we equip these students to be better listeners and train for new jobs we don’t even know yet? How can we make sure our students are getting the best education for them? But how do we also not take away that component of collaboration and critical thinking and working together?”

Binnie concluded of her school’s AI pilot program: “We’re looking forward to it, seeing how it goes and how we can integrate it into other subjects as well.”

St. Paul’s Lutheran Church and School

Where: 1376 Felspar St., Pacific Beach.

Info: stpaulspb.com, (858) 272-6282.

Church: In February of 1943, a small group of people was moved to constitute St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in an empty store at 1570 Garnet Ave. in Pacific Beach.

The Rev. A.J. Brommer, who had originally been called as a missionary for the area, was the first pastor. Five lots, which are included in the present church and school campus, were purchased in 1943 for a total of $1,180.

The building was constructed on the property at the corner of Felspar and Gresham streets in June 1945. The total cost of construction was $6,000.

School: The congregation felt a strong need for a Christian education for their children. In September of 1947, a one-room school with a capacity for 30 students was built, and St. Paul’s Lutheran School was founded.

Education

Parents in England to pay more for school lunches as caterers blame rising costs | School meals

Parents across England are facing higher prices for school lunches as the new school year begins, with caterers blaming the government’s national insurance increase alongside rising food and energy costs.

Lunch providers say increases in staffing costs, including employer national insurance contributions announced by the chancellor last year, have added “significant extra pressure” to their budgets.

Food price inflation is also driving costs higher, pushing consumer prices above forecasts this summer. Prices for food and non-alcoholic drinks rose 4.9% in the year to July and are now 37% higher than five years ago, according to data from the Office for National Statistics.

Letters sent to parents informing them of price rises acknowledged the strain on families but said changes were unavoidable if catering services were to remain viable.

At Coleham primary in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, meals will rise by 10p a day to £2.60 from September 2025 because of “rising operational costs”. Bridge Hall primary in Stockport, Greater Manchester, said charges would rise by 8p to £2.73 – a 3.1% increase “in line with UK inflation”. Fernhurst Junior in Portsmouth confirmed a new daily rate of £2.86, and West Vale Academy in Halifax £2.60. Kingskerswell Church of England primary school in Newton Abbott raised costs to £2.75, up by 30p.

Ministers have promised to widen eligibility for free meals from 2026 but schools have said they cannot wait that long.

About a quarter of pupils in Englandcurrently qualify for free school meals, but campaigners say the government’s £2.61-a-meal funding is no longer sufficient, leaving schools to plug the gap.

“All schools will be navigating the impact of rapidly rising food costs,” said Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the school leaders’ union the National Association of Head Teachers. “Sometimes school dinners are the only reliable nutritious meal a child will get that day, so for this to be of worse quality or more expensive is extremely concerning.”

Judith Gregory, chair of LACA, which represents public and private sector caterers in schools, said they were “doing everything possible to shield families by streamlining menus, adapting recipes and finding efficiencies”.

But Gregory said caterers’ efforts were not enough, and schools were having to raise costs for others to cover the funding shortfall.

“Food inflation has driven up the cost of school meals by more than 20% since 2020,” she said. “Without urgent action to raise funding to at least £3.45 per meal, schools will be forced to reduce options or introduce less costly ingredients, while families just above the free school meal threshold face higher charges.”

Gregory said the recent increase in employer’s national insurance as well as annual pay increases for workers were adding “significant extra pressure” on top of already steep rises in food costs.

Barbara Crowther, the children’s food campaign manager at Sustain, a group advocating for food and agriculture policies and practices that enhance health and welfare, said the “true cost of a healthy, sustainable school meal” was now closer to £3-£3.20, depending on the size of schools and catering operations.

Campaigners argue that the higher charges will disproportionately affect low-income families, with many falling just below the threshold for free school meals.

“School leaders are deeply worried,” said Whiteman. “They are seeing more families struggling and more children living in poverty – child hunger is a real concern. There is only so long schools can keep swallowing the increases. For many, putting up the cost of meals is now the only option.”

The Department for Education said the government has taken “a historic step to tackle the stain of child poverty, offering free school meals to every child from a household that claims universal credit from the start of the 2026 school year”.

A spokesperson added: “The new entitlement will be fully funded and lift 100,000 children entirely out of poverty. To make sure meals are high-quality and nutritious, the government is working with experts to revise the school food standards, and we will continue to work closely with the sector to keep meal rates under review.”

The Guardian was unable to reach schools for comment.

Education

Meet the three-year-olds helping anxious teens spend more time in school

BBC

BBCSiena never thought she’d be taking lessons in communication and confidence from a three-year-old.

She is part of a scheme that pairs teenagers with toddlers from a local nursery in a bid to help increase school attendance and engagement.

The 13-year-old says she had a “lot of anxiety” so would never be in school, but “coming here has taught me more about how to communicate and be more confident and it’s funny a toddler is teaching us things.”

While she didn’t think the project would help increase her attendance, it has actually more than doubled.

“It’s really helped me,” she says. “The toddler I’m paired with has grown so much and it makes me so happy to see,” she tells the BBC’s Morning Live.

Morning Live returns on Monday at 0930am. Watch this and more here.

As the summer holiday ends and the new school year begins, many parents will be worrying about their child’s attendance and engagement.

The issue of school avoidance is a big one and one charity has created this mentoring programme with its research suggesting that a disengaged teenager having responsibility for a younger child in a controlled setting can have a positive impact on their engagement with school and learning.

Since the pandemic, school absence has almost doubled – in the 2024/25 academic year, 17.79% of pupils were persistently absent meaning they missed 10% or more school sessions.

Data shows that just 10 days of absence can halve the chance of a student getting at least a grade 5 in English and Maths.

Miller, 12, another pupil participating in the scheme says he struggles to stay in class because he has a lot of energy, but that the sessions have helped him focus more on his school work.

“I was a bit nervous and it took me two weeks to say yes to the project as I was really shy.”

Miller has been paired with three-year-old Andrew and says they are now really close.

“When he sees me he runs up to me and gives me a hug.”

As well as developing his confidence, Miller adds that the sessions have made him feel calmer and less energetic.

Sam Marcus is the director of services at Power2, the charity that runs this scheme, currently only in London and Manchester.

It offers various mentoring programmes to children of all ages and over the years has helped 27,000 children and young people to re-engage with school.

This particular project works across a 16-week period where teenagers visit a local nursery once a week and mentor a child.

The pairing is well thought out – “it’s often based on personalities so a really vibrant toddler might be paired with a shy teenager or a timid toddler is matched with a boisterous teen which helps create a much softer side to them.”

The aim is that the bond between the toddler and teen will help build confidence and accountability that encourages them to then turn up to lessons and “a sense of responsibility to young people who often aren’t given those positions”.

“If a child is disruptive in class, they often aren’t given those opportunities to prove themselves to be more than that,” she says.

“We help the teen become a positive role model for that child,” she adds. The teenagers also have reflective sessions after the nursery visit to learn more about building healthy relationships and positive attitudes.

According to Power2, 78% young people on the scheme improve their attitude to learning and 83% of them have improved self esteem.

Often the toddler also has additional needs such as speech and language delays or difficulty making friends and Lisa, who teaches at one of the nursery’s involved in the project says it has a big impact on the children.

“They love having that special person each Friday,” she says. “It’s lovely to see them having that one to one time and the kids running up hugging the teens every week.”

How can you help your child with attendance?

This scheme is one small programme aiming to help with the very complex issue of school advoidance.

The Department for Education provides guidance on what to do if your child is struggling to attend school.

Dr Weisberg, a consultant clinical psychologist who works with young people who feel disconnected from their education, says often children find it hard to engage with education because “there are lots of rules at school and none of them are under the kid’s control”.

In contrast, this programme “gives them a responsibility and empowerment to learn from what works and what doesn’t and they feel like they are making a real difference”.

He gives three tips on how parents can work with their child to improve their attendance:

- Raise it with the school – “Make sure the school are on the same page and there are lots of charities and support available to make things better.”

- Give the child agency – “Be available. I recommend parents spend at least 10 minutes a day with each child without distractions like screens or phones.”

- Follow their lead – With younger children, it’s important for parents to play with them and follow their lead which can “foster healthy relationships and confidence”.

Sue Armstrong, a clinical service manager at relationship support charity Relate, says other ways to support your child through school anxiety and avoidance include:

- Avoid blaming yourself and your child – “It’s important to try not to feel guilty or that this is somehow your fault”.

- Look forward to positive things – “Continuing ‘normal’ family events will help all of you. Finding time, when you can, for your own interests, as a couple and individually, is vital”.

- Accept there will be ups and downs – “You may feel you’re being pulled in every direction, having to keep a job going and support your child when they may be feeling very anxious and confused, that there’s no space left for you”.

Education

AI Has Broken High School and College

This is Atlantic Intelligence, a newsletter in which our writers help you wrap your mind around artificial intelligence and a new machine age. Sign up here.

Another school year is beginning—which means another year of AI-written essays, AI-completed problem sets, and, for teachers, AI-generated curricula. For the first time, seniors in high school have had their entire high-school careers defined to some extent by chatbots. The same applies for seniors in college: ChatGPT released in November 2022, meaning unlike last year’s graduating class, this year’s crop has had generative AI at its fingertips the whole time.

My colleagues Ian Bogost and Lila Shroff both recently wrote articles about these students and the state of AI in education. (Ian, a university professor himself, wrote about college, while Lila wrote about high school.) Their articles were striking: It is clear that AI has been widely adopted, by students and faculty alike, yet the technology has also turned school into a kind of free-for-all.

I asked Lila and Ian to have a brief conversation about their work—and about where AI in education goes from here.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Lila Shroff: We’re a few years into AI in schools. Is the conversation maturing or changing in some way at universities?

Ian Bogost: Professors are less surprised that it exists, but there is maybe a bit of a blind spot to the state of adoption among students. I saw a panic in 2022, 2023—like, Oh my God, this can do anything. Or at least there were questions. Can this do everything? How much is my class at risk? Now I think there’s more of a sense of, Well, this thing still exists, but we have time. We don’t have to worry about it right away. And that might actually be a worse reaction than the original.

Lila: The blind-spot language rings true to the high-school environment too. I spoke to some high schoolers—granted this was quite a small sample—but basically it sounds like everybody is using this all the time for everything.

Ian: Not just for school, right? Anything they want to do, they’re asking ChatGPT now.

Lila: I was a sophomore in college when ChatGPT came out, so I witnessed some of this firsthand. There was much more anxiety—it felt like the rules were unclear. And I think both of our stories touched on the fact that for this incoming class of high-school and college seniors, they’ve barely had any of those four years without ChatGPT. Whatever sort of stigma or confusion that might have been there in earlier years is fading, and it’s becoming very much default and normalized.

Ian: Normalization is the thing that struck me the most. That is not a concept that I think the teachers have wrapped their heads around. Teachers and faculty also have been adopting AI carefully or casually—or maybe even in a more professional way, to write articles or letters of recommendation, which I’ve written about. There’s still this sense that it’s not really a part of their habit.

Lila: I looked into teachers at the K–12 level for the article I wrote. Three in 10 teachers are using AI weekly in some way.

Ian: Some kind of redesign of educational practice might be required, which is easy for me to say in an article. Instead of an answer, I have an approach to thinking about the answer that has been bouncing around in my brain. Are you familiar with the concept in software development called technical debt? In the software world, you make the decision about how to design or implement a system that feels good and right at the time. And maybe you know it’s going to be a bad idea in the long run, but for now, it makes sense and it is convenient. But you never get around to really making it better later on, and so you have all these nonoptimal aspects of your infrastructure.

That’s the state I feel like we’re in, at least in the university. It’s a little different in high school, especially in public high school, with these different regulatory regimes at work. But we accrued all this pedagogical debt, and not just since AI—there are aspects of teaching that we ought to be paying more attention to or doing better, like, this class needs to be smaller, or these kinds of assignments don’t work unless you have a lot of hands-on iterative feedback. We’ve been able to survive under the weight of pedagogical debt, and now something snapped. AI entered the scene and all of those bad or questionable—but understandable—decisions about how to design learning experiences are coming home to roost.

Lila: I agree that AI is a breaking point in education. One answer that seems to be emerging at the high-school level is a more practical, skills-based education. The College Board, for instance, has announced two new AP courses—AP Business and AP Cybersecurity. But there’s another group of people who are really concerned about how overreliance on these tools erodes critical-thinking skills, and maybe that means everyone should go read the classics and write their essays in cursive handwriting.

Ian: My young daughter has been going to this set of classes outside of school where she learned how to wire an outlet. We used to have shop class and metal class, and you could learn a trade, or at least begin to, in high school. A lot of that stuff has been disinvested. We used to touch more things. Now we move symbols around, and that’s kind of it.

I wonder if this all-or-nothing nature of AI use has something to do with that. If you had a place in your day as a high-school or college student where you just got to paint, or got to do on-the-ground work in the community, or apply the work you did in statistics class to solve a real-world problem—maybe that urge to just finish everything as rapidly as possible so you can get onto the next thing in your life would be less acute. The AI problem is a symptom of a bigger cultural illness, in a way.

Lila: Students are using AI exactly as it has been designed, right? They’re just making themselves more productive. If they were doing the same thing in an office, they might be getting a bonus.

Ian: Some of the students I talked to said, Your boss isn’t going to care how you get things done, just that they get done as effectively as possible. And they’re not wrong about that.

Lila: One student I talked to said she felt there was really too much to be done, and it was hard to stay on top of it all. Her message was, maybe slow down the pace of the work and give students more time to do things more richly.

Ian: The college students I talk to, if you slow it all down, they’re more likely to start a new club or practice lacrosse one more day a week. But I do love the idea of a slow-school movement to sort of counteract AI. That doesn’t necessarily mean excluding AI—it just means not filling every moment of every day with quite so much demand.

But you know, this doesn’t feel like the time for a victory of deliberateness and meaning in America. Instead, it just feels like you’re always going to be fighting against the drive to perform even more.

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences3 months ago

Events & Conferences3 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months ago

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months agoDonald Trump suggests US government review subsidies to Elon Musk’s companies

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoAstrophel Aerospace Raises ₹6.84 Crore to Build Reusable Launch Vehicle