Education

Six Sunderland schools join new fellowship to overcome challenges

Jim ScottBBC News, North East and Cumbria

BBC

BBCA pupil who is urging people to visit his suburb before “casting judgement”, says a new scheme will show his community is ready for a new start.

Salah, who is in Year 10 at Academy 360 in Pennywell, Sunderland, is among about 2,000 pupils who will benefit from the scheme, education bosses said.

The Pennywell Fellowship, made up of six schools and believed to be one of the “first of its kind” in England, will share resources to create links with employers, improve school-parent relationships and boost attendance.

The scheme is being developed in an area where support systems have been “steadily eroded” by cuts. The government has welcomed the plan.

It is hoped the project, which includes Christ’s College, St Anne’s Primary, North View, South Hylton and Highfield Academies, could be used as a blueprint for other schools across the country.

Salah, who hopes to become a doctor, said there was a perception that Pennywell was deprived.

“But I’ll tell these people come and live in Pennywell, see how it is and then cast your judgement,” he said.

“It’s a very nice place, the people are nice, everything is chill and and it’s a good community.”

The fellowship said that “low school attendance” was undermining learning, while “too many young people” were leaving school without support to find jobs.

Julie Normanton, principal at Christ College, said schools had been “competing against each other”, despite wanting the same positive outcomes, and that the scheme would bring them together helping all six improve.

“Traditionally there is a temptation with schools to work very much in isolation.

“[They] see local schools as competitors, because we’re competing to get the numbers through the doors, competing to get the best results.

“But actually we are all trying to do the same thing and make lives better for the children – our teachers are very excited.”

Parents in the area “want the very, very best for their young people but they can’t always access it in a way other families can” said Sally Newton, chief executive of The Laidlaw Schools Trust.

She said she hoped that would change through the new partnership.

Salah said he was looking forward to “being helpful” and doing “something that contributes to society, people and the future”.

Education

How to use ChatGPT at university without cheating: ‘Now it’s more like a study partner’ | University guide

For many students, ChatGPT has become as standard a tool as a notebook or a calculator.

Whether it’s tidying up grammar, organising revision notes, or generating flashcards, AI is fast becoming a go-to companion in university life. But as campuses scramble to keep pace with the technology, a line is being quietly drawn. Using it to understand? Fine. Using it to write your assignments? Not allowed.

According to a recent report from the Higher Education Policy Institute, almost 92% of students are now using generative AI in some form, a jump from 66% the previous year.

“Honestly, everyone is using it,” says Magan Chin, a master’s student in technology policy at Cambridge, who shares her favourite AI study hacks on TikTok, where tips range from chat-based study sessions to clever note-sifting prompts.

“It’s evolved. At first, people saw ChatGPT as cheating and [thought] that it was damaging our critical thinking skills. But now, it’s more like a study partner and a conversational tool to help us improve.”

It has even picked up a nickname: “People just call it ‘Chat’,” she says.

Used wisely, it can be a powerful self-study tool. Chin recommends giving it class notes and asking it to generate practice exam questions.

“You can have a verbal conversation like you would with a professor and you can interact with it,” she points out, adding that it can also make diagrams and summarise difficult topics.

Jayna Devani, the international education lead at ChatGPT’s US-based developer, OpenAI, recommends this kind of interaction. “You can upload course slides and ask for multiple-choice questions,” she says. “It helps you break down complex tasks into key steps and clarify concepts.”

Still, there is a risk of overreliance. Chin and her peers practise what they call the “pushback method”.

“When ChatGPT gives you an answer, think about what someone else might say in response,” she says. “Use it as an alternative perspective, but remember it’s just one voice among many.” She recommends asking how others might approach this differently.

That kind of positive use is often welcomed by universities. But academic communities are grappling with the issue of AI misuse and many lecturers have expressed grave concerns about the impact on the university experience.

Graham Wynn, pro-vice-chancellor for education at Northumbria University, says using it to support and structure assessments is permitted, but students should not rely on the knowledge and content of AI. “Students can quickly find themselves running into trouble with hallucinations, made-up references and fictitious content.”

Northumbria, like many universities, has AI detectors in place and can flag submissions where there is potential overreliance. At University of the Arts London (UAL) students are required to keep a log of their AI use to situate it in their individual creative process.

As with most emerging technologies, things are moving quickly. The AI tools students are using today are already common in the workplaces they will be entering tomorrow. But university is not just about the result, it is about the process and the message from educators is clear: let AI assist your learning, not replace it.

“AI literacy is a core skill for students,” says a UAL spokesperson, before adding: “Approach it with both curiosity and awareness.”

Education

Love coursework, hate exams? If you’re choosing a university place, don’t forget to check how you will be tested | University guide

For 18-year-old Rose Kade from London, deciding between studying geography or maths at university is not just about the subject, it’s about how she will be assessed.

“I don’t like exams,” she says. “I feel like anything can happen on the day, and I find it hard being judged entirely on that one performance.” She prefers coursework: “I like building things up over time. It’s less stressful and if I have a bad day it doesn’t affect my grade.”

Kade is not alone. For some time now, universities have been trying to ensure that students are exposed to a variety of assessment styles, with many moving away from traditional written exams towards longer-term projects, presentations and online assignments. There is particular emphasis on dissertations because of the useful research and data analysis skills that they help develop, as well as a move towards integrating assessments into the learning experience.

Universities UK’s director of policy, Steph Harris, says students can expect a range of assessment types depending on the course. “Some qualifications rely more on coursework or observation-based assessment, while others may require more traditional exams. Many will include types of assessment needed to meet professional standards, including medical courses,” she adds.

One factor accelerating this shift is AI. According to Sue Attewell from Jisc, an organisation that provides digital resources in the higher education sector, institutions are trying to AI-proof assessments by trying out a variety of styles. The emphasis, she says, is on verbal discussions where students have no time to prepare and can’t easily predict the questions that will come up.

“The historic methods [of assessment] are not really fit for purpose in the modern world and we have seen a lot of promotion of authentic assessments. We’re seeing a wider mix of methods now. That might include presentations, vivas, verbal quizzes, and question-led discussions after presentations, not just written exams,” she says.

Manuel Souto Otero from the school of education at the University of Bristol thinks students mulling their course options should look at the content as well as how it is going to be examined. “Think about the variety of assessment types, but also the frequency and whether you prefer working alone or in a group. In some cases students can have a range of assignments they can choose from.”

Of course, not every assessment will be in your comfort zone and that is not necessarily a bad thing. “There’s value in being exposed to different styles,” he adds. “But if you know that you are going to clearly struggle with certain types of assessment, you may want to know what you are likely to face.”

Rachel Gillam, deputy director of student recruitment at the University of Nottingham, says it can be a personal thing. “If this is something that is significant to you, we’d recommend that you review the more detailed course information on the prospectuses of the courses that you are considering. All universities should provide this information in more detail, once you secure an offer.”

Still, assessment is not everything, and it should not be the be-all and end-all. It is important, especially for students with additional needs, but so is the course content, the learning environment, and what comes after. In the end, how you are assessed may not define your degree, but it could shape how you experience it.

One thing to consider is that the third term might be a little quieter than expected. With many assessments taking place early in summer term, students are increasingly finding themselves with time on their hands. That is not necessarily wasted, especially if you plan it well.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, says the third term is “increasingly empty” and there is frustration, particularly among parents, that the academic year is ending early.

The change, he says, is partly because many universities are shifting from a three-term academic year to a two-semester system. “You can have your exams quite early in the summer term and you’re paying £9,250 and not going back until late September or early October. I’m surprised it is not a mini-scandal,” he says.

However, this is not necessarily wasted, especially if you plan it well. “If they are doing a final-year dissertation, this can be highly consuming, but if they have free time there’s an opportunity to gain additional skills through non-formal learning, volunteering, sports, networking, work experience, or something creative,” says Souto Otero. “All of that can be highly valuable.”

Education

‘I regret pushing my daughter into school until she broke’

Ben SchofieldPolitics correspondent, BBC East

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCThe start of the school year saw the Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson warn parents about the need for children to attend classes.

Data suggests half of pupils who missed lessons in the first week of term last year went on to become persistently absent.

But school leaders say they are seeing more children who find attending school too traumatic.

What is it like having a child with what psychologists call emotionally based school avoidance and what should be done to help?

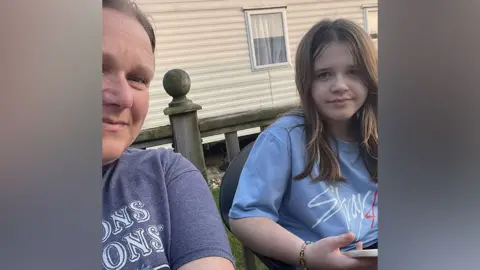

Family handout

Family handoutThe final time Julie took her daughter to school in July 2023, a member of staff congratulated her.

Rosie, who was then eight, was “wearing a dirty pyjama top, a pair of jogging bottoms, a pair of trainers with no socks, she had her headphones on, she was holding a teddy”, Julie recalls.

“I walked into school and the [special needs co-ordinator] then said to me ‘well done, you got her here’.”

But for Julie, 48, it was not a “win”.

“She couldn’t even speak, she hadn’t eaten, she had maybe three or four hours sleep.

“But I’d done a good job as a parent for making her go to school?”

Family handout

Family handoutAt the time Rosie, who has autism, was in Year Three at a primary school in Northamptonshire.

Julie says her daughter had struggled with the school environment since her time in nursery and is now educated out of school.

Rosie, she recalls, was “in fight and flight the whole time” she was in the classroom, which “just overwhelmed her”.

Eventually Rosie was “begging not to leave” the house for school and was self-harming, sometimes on the school run.

“She would have night terrors – she would be up screaming, if she went to sleep at all.

“It just felt as if I was walking her into the lion’s den every single day,” she says.

Meanwhile, Julie and her husband James received letters and home visits from school staff about Rosie’s attendance.

“It was very lonely.

“All of a sudden there’s these letters and people are talking about fines and I was lost.”

On that final say Julie says she “dragged” Rosie to school because “that was the expectation”.

Now she wishes she had taken Rosie out of school earlier.

“But I also feel that if I hadn’t have got to the point… where she broke, I would never have known if it had worked,” she says.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCBased on Rosie’s reaction to school, an educational psychologist who assessed her noted she had “emotionally based school avoidance” or EBSA, a condition school leaders say they are encountering more.

Anna Hewes, the head teacher of Prince William School, a 1,400-pupil secondary in Oundle, Northamptonshire, says schools are seeing a “big increase” in EBSA among pupils in Year Seven, Eight and Nine.

The transition to secondary school is, she adds, a “key time” and at the start of the school year EBSA is “at the forefront of our minds because of the new year sevens coming through”.

The “noises, the bustling nature of a school – the busyness, all the classes walking around” make it a “real challenge” for those with sensory needs, she says.

But more generally “it’s very tough to be a teenager these days”.

Smartphones and social media, she adds, mean “young people can’t escape anymore”.

“It definitely is a post-Covid spike and these young people are genuinely really struggling to step over the threshold of the school and sometimes leave their bedrooms.”

DJ McLaren/BBC

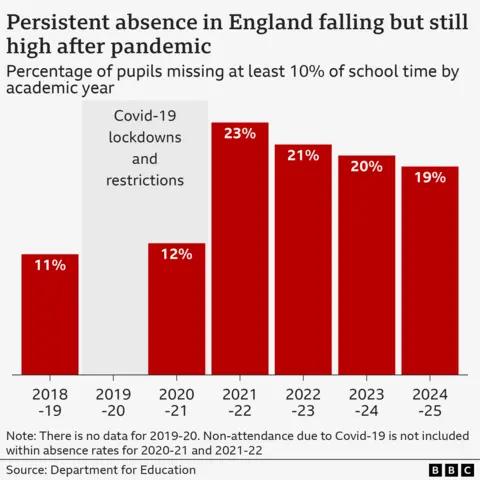

DJ McLaren/BBCAcross England, rates of “persistent absence” – when pupils miss 10% or more of lessons – have remained high since the pandemic.

Last academic year almost 19% of pupils were persistently absent, compared with 11% in 2018/19.

Mrs Hewes says EBSA is a “significant part” of the issue.

A lack of reliable data, however, means it is difficult to know how big a part.

Mrs Hewes says Prince William Academy prioritises “inclusion” and has recruited an assistant head teacher for “belonging”.

It has also opened a specialist “school-within-a-school” for pupils with EBSA, funded by North Northamptonshire Council. Four students have been enrolled so far and by 2028 it expects to see 48.

Jenny Nimmo, the head of inclusion at East Midlands Academy Trust, which runs Prince William Academy, says the unit will have more “homely” classrooms and on-site mental health provision.

She hopes it will be “future proof” because EBSA “isn’t going away”.

There are, she adds, “more and more young people” with “emotionally based school avoidance and indeed anxiety”.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCThe Compass Centre in Luton also help pupils with EBSA access education.

Dr Joanne Summers, Luton Borough Council’s principal educational psychologist, says the condition can appear suddenly but “when you look back, there has been anxiety around being in school” and one incident might be a “catalyst”.

Intervening early, she adds, is important, as falling behind on school work and losing contact with friends can make anxiety worse.

Dr Summers says Luton has been trying to move away from seeing school absences as “defiance and truancy”.

“We are being curious about what’s going on for that young person, why is it that they are behaving in this way,” she adds.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCGeoff Barton, a former head teacher in Suffolk and previous general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, says there should be more “emphasis on the humanity of our schools” rather than “draconian discipline” over absences.

He is researching special educational needs (Send) provision for the left-leaning think tank the Institute for Public Policy Research.

He says the people he is speaking to are “universally saying” that anxiety among pupils has increased.

But the “age of anxiety” is only one reason for persistent absence.

Another is poverty, while he says there is also a “long shadow in education of Covid” when “schools started to feel a bit more of an optional decision”.

Cornelia Andrecut, the executive director of children’s services for North Northamptonshire Council, said the authority has offered training courses for schools to learn strategies to support children with EBSA.

The government says it will spend £740m creating “more specialist places in mainstream schools” and placing Send leads in 1,000 new family hubs.

A Department for Education spokesperson says: “Schools should take a ‘support first’ approach for children who are facing barriers to regular school attendance, and we are expanding access to mental health support teams in all schools, ensuring that every pupil has access to early support services in their community.”

Family handout

Family handoutFor Julie, taking Rosie out of school was “not a lifestyle choice” but was prompted by “trauma and distress” that her daughter is still recovering from.

Does she regret pushing Rosie to attend school?

“Yeah – definitely.

“I always wonder if there was a bit of trust broken between us as mum and daughter when I still took her into that place when it was that bad.”

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms1 month ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers3 months ago

Jobs & Careers3 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Funding & Business3 months ago

Funding & Business3 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries