Events & Conferences

Responsible AI in the generative era

In recent years, and even recent months, there have been rapid and dramatic advances in the technology known as generative AI. Generative AI models are trained on inconceivably massive collections of text, code, images, and other rich data. They are now able to produce, on demand, coherent and compelling stories, news summaries, poems, lyrics, paintings, and programs. The potential practical uses of generative AI are only just beginning to be understood but are likely to be manifold and revolutionary and to include writing aids, creative content production and refinement, personal assistants, copywriting, code generation, and much more.

There is thus considerable excitement about the transformations and new opportunities that generative AI may bring. There are also understandable concerns — some of them new twists on those of traditional responsible AI (such as fairness and privacy) and some of them genuinely new (such as the mimicry of artistic or literary styles). In this essay, I survey these concerns and how they might be addressed over time.

I will focus primarily on technical approaches to the risks, while acknowledging that social, legal, regulatory, and policy mechanisms will also have important roles to play. At Amazon, our hope is that such a balanced approach can significantly reduce the risks, while still preserving much of the excitement and usefulness of generative AI.

What is generative AI?

To understand what generative AI is and how it works, it is helpful to begin with the example of large language models (LLMs). Imagine the thought experiment in which we start with some sentence fragment like Once upon a time, there was a great …, and we poll people on what word they would add next. Some might say wizard, others might say queen, monster, and so on. We would also expect that given the fairy tale nature of the fragment, words such as apricot or fork would be rather unlikely suggestions.

If we poll a large enough population, a probability distribution over next words would begin to emerge. We could then randomly pick a word from that distribution (say wizard), and now our sequence would be one word longer — Once upon a time, there was a great wizard … — and we could again poll for the next word. In this manner we could theoretically generate entire stories, and if we restarted the whole process, the crowd would produce an entirely different narrative due to the inherent randomness.

Dramatic advances in machine learning have effectively made this thought experiment a reality. But instead of polling crowds of people, we use a model to predict likely next words, one trained on a massive collection of documents — public collections of fiction and nonfiction, Wikipedia entries and news articles, transcripts of human dialogue, open-source code, and much more.

If the training data contains enough sentences beginning Once upon a time, there was a great …, it will be easy to sample plausible next words for our initial fragment. But LLMs can generalize and create as well, and not always in ways that humans might expect. The model might generate Once upon a time, there was a great storm based on occurrences of tremendous storm in the training data, combined with the learned synonymy of great and tremendous. This completion can happen despite great storm never appearing verbatim in the training data and despite the completions more expected by humans (like wizard and queen).

The resulting models are just as complex as their training data, often described by hundreds of billions of numbers (or parameters, in machine learning parlance), hence the “large” in LLM. LLMs have become so good that not only do they consistently generate grammatically correct text, but they create content that is coherent and often compelling, matching the tone and style of the fragments they were given (known as prompts). Start them with a fairy tale beginning, and they generate fairy tales; give them what seems to be the start of a news article, and they write a news-like article. The latest LLMs can even follow instructions rather than simply extend a prompt, as in Write lyrics about the Philadelphia Eagles to the tune of the Beatles song “Get Back”.

Generative AI isn’t limited to text, and many models combine language and images, as in Create a painting of a skateboarding cat in the style of Andy Warhol. The techniques for building such systems are a bit more complex than for LLMs and involve learning a model of proximity between text and images, which can be done using data sources like captioned photos. If there are enough images containing cats that have the word cat in the caption, the model will capture the proximity between the word and pictures of cats.

The examples above suggest that generative AI is a form of entertainment, but many potential practical uses are also beginning to emerge, including generative AI as a writing tool (Shorten the following paragraphs and improve their grammar), for productivity (Extract the action items from this meeting transcript), for creative content (Propose logo designs for a startup building a dog-walking app), for simulating focus groups (Which of the following two product descriptions would Florida retirees find more appealing?), for programming (Give me a code snippet to sort a list of numbers), and many others.

So the excitement over the current and potential applications of generative AI is palpable and growing. But generative AI also gives rise to some new risks and challenges in the responsible use of AI and machine learning. And the likely eventual ubiquity of generative models in everyday life and work amplifies the stakes in addressing these concerns thoughtfully and effectively.

So what’s the problem?

The “generative” in generative AI refers to the fact that the technology can produce open-ended content that varies with repeated tries. This is in contrast to more traditional uses of machine learning, which typically solve very focused and narrow prediction problems.

For example, consider training a model for consumer lending that predicts whether an applicant would successfully repay a loan. Such a model might be trained using the lender’s data on past loans, each record containing applicant information (work history, financial information such as income, savings, and credit score, and educational background) along with whether the loan was repaid or defaulted.

The typical goal would be to train a model that was as accurate as possible in predicting payment/default and then apply it to future applications to guide or make lending decisions. Such a model makes only lending outcome predictions and cannot generate fairy tales, improve grammar, produce whimsical images, write code, and so on. Compared to generative AI, it is indeed a very narrow and limited model.

But the very limitations also make the application of certain dimensions of responsible AI much more manageable. Consider the goal of making our lending model fair, which would typically be taken to mean the absence of demographic bias. For example, we might want to make sure that the error rate of the predictions of our model (and it generally will make errors, since even human loan officers are imperfect in predicting who will repay) is approximately equal on men and women. Or we might more specifically ask that the false-rejection rate — the frequency with which the model predicts default by an applicant who is in fact creditworthy — be the same across gender groups.

Once armed with this definition of fairness, we can seek to enforce it in the training process. In other words, instead of finding a model that minimizes the overall error rate, we find one that does so under the additional condition that the false-rejection rates on men and women are approximately equal (say, within 1% of each other). We might also want to apply the same notion of fairness to other demographic properties (such as young, middle aged, and elderly). But the point is that we can actually give reasonable and targeted definitions of fairness and develop training algorithms that enforce them.

It is also easy to audit a given model for its adherence to such notions of fairness (for instance, by estimating the error rates on both male and female applicants). Finally, when the predictive task is so targeted, we have much more control over the training data: we train on historical lending decisions only, and not on arbitrarily rich troves of general language, image, and code data.

Now consider the problem of making sure an LLM is fair. What might we even mean by this? Well, taking a cue from our lending model, we might ask that the LLM treat men and women equally. For instance, consider a prompt like Dr. Hanson studied the patient’s chart carefully, and then … . In service of fairness, we might ask that in the completions generated by an LLM, Dr. Hanson be assigned male and female pronouns with roughly equal frequency. We might argue that to do otherwise perpetuates the stereotype that doctors are typically male.

But then should we not also do this for mentions of nurses, firefighters, accountants, pilots, carpenters, attorneys, and professors? It’s clear that measuring just this one narrow notion of fairness will quickly become unwieldy. And it isn’t even obvious in what contexts it should be enforced. What if the prompt described Dr. Hanson as having a beard? What about the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA)? Should mention of a WNBA player in a prompt elicit male pronouns half the time?

Defining fairness for LLMs is even murkier than we suggest above, again because of the open-ended content they generate. Let’s turn from pronoun choices to tone. What if an LLM, when generating content about a woman, uses an ever-so-slightly more negative tone (in choice of words and level of enthusiasm) than when generating content about a man? Again, even detecting and quantifying such differences would be a very challenging technical problem. The field of sentiment analysis in natural-language processing might suggest some possibilities, but currently, it focuses on much coarser distinctions in narrower settings, such as distinguishing positive from negative sentiment in business news articles about particular corporations.

So one of the prices we pay for the rich, creative, open-ended content that generative AI can produce is that it becomes commensurately harder (compared to traditional predictive ML) to define, measure, and enforce fairness.

From fairness to privacy

In a similar vein, let’s consider privacy concerns. It is of course important that a consumer lending model not leak information about the financial or other data of the individual applicants in the training data. (One way this can happen is if model predictions are accompanied by confidence scores; if the model expresses 100% confidence that a loan application will default, it’s likely because that application, with a default outcome, was in the training data.) For this kind of traditional, more narrow ML, there are now techniques for mitigating such leaks by making sure model outputs are not overly dependent on any particular piece of training data.

But the open-ended nature of generative AI broadens the set of concerns from verbatim leaks of training data to more subtle copying phenomena. For example, if a programmer has written some code using certain variable names and then asks an LLM for help writing a subroutine, the LLM may generate code from its training data, but with the original variable names replaced with those chosen by the programmer. So the generated code is not literally in the training data but is different only in a cosmetic way.

There are defenses against these challenges, including curation of training data to exclude private information, and techniques to detect similarity of code passages. But more subtle forms of replication are also possible, and as I discuss below, this eventually bleeds into settings where generative AI reproduces the “style” of content in its training data.

And while traditional ML has begun developing techniques for explaining the decisions or predictions of trained models, they don’t always transfer to generative AI, in part because current generative models sometimes produce content that simply cannot be explained (such as scientific citations that don’t exist, something I’ll discuss shortly).

The special challenges of responsible generative AI

So the usual concerns of responsible AI become more difficult for generative AI. But generative AI also gives rise to challenges that simply don’t exist for predictive models that are more narrow. Let’s consider some of these.

Toxicity. A primary concern with generative AI is the possibility of generating content (whether it be text, images, or other modalities) that is offensive, disturbing, or otherwise inappropriate. Once again, it is hard to even define and scope the problem. The subjectivity involved in determining what constitutes toxic content is an additional challenge, and the boundary between restricting toxic content and censorship may be murky and context- and culture-dependent. Should quotations that would be considered offensive out of context be suppressed if they are clearly labeled as quotations? What about opinions that may be offensive to some users but are clearly labeled as opinions? Technical challenges include offensive content that may be worded in a very subtle or indirect fashion, without the use of obviously inflammatory language.

Hallucinations. Considering the next-word distribution sampling employed by LLMs, it is perhaps not surprising that in more objective or factual use cases, LLMs are susceptible to what are sometimes called hallucinations — assertions or claims that sound plausible but are verifiably incorrect. For example, a common phenomenon with current LLMs is creating nonexistent scientific citations. If one of these LLMs is prompted with the request Tell me about some papers by Michael Kearns, it is not actually searching for legitimate citations but generating ones from the distribution of words associated with that author. The result will be realistic titles and topics in the area of machine learning, but not real articles, and they may include plausible coauthors but not actual ones.

In a similar vein, prompts for financial news stories result not in a search of (say) Wall Street Journal articles but news articles fabricated by the LLM using the lexicon of finance. Note that in our fairy tale generation scenario, this kind of creativity was harmless and even desirable. But current LLMs have no levers that let users differentiate between “creativity on” and “creativity off” use cases.

Intellectual property. A problem with early LLMs was their tendency to occasionally produce text or code passages that were verbatim regurgitations of parts of their training data, resulting in privacy and other concerns. But even improvements in this regard have not prevented reproductions of training content that are more ambiguous and nuanced. Consider the aforementioned prompt for a multimodal generative model Create a painting of a skateboarding cat in the style of Andy Warhol. If the model is able to do so in a convincing yet still original manner because it was trained on actual Warhol images, objections to such mimicry may arise.

Plagiarism and cheating. The creative capabilities of generative AI give rise to worries that it will be used to write college essays, writing samples for job applications, and other forms of cheating or illicit copying. Debates on this topic are happening at universities and many other institutions, and attitudes vary widely. Some are in favor of explicitly forbidding any use of generative AI in settings where content is being graded or evaluated, while others argue that educational practices must adapt to, and even embrace, the new technology. But the underlying challenge of verifying that a given piece of content was authored by a person is likely to present concerns in many contexts.

Disruption of the nature of work. The proficiency with which generative AI is able to create compelling text and images, perform well on standardized tests, write entire articles on given topics, and successfully summarize or improve the grammar of provided articles has created some anxiety that some professions may be replaced or seriously disrupted by the technology. While this may be premature, it does seem that generative AI will have a transformative effect on many aspects of work, allowing many tasks previously beyond automation to be delegated to machines.

What can we do?

The challenges listed above may seem daunting, in part because of how unfamiliar they are compared to those of previous generations of AI. But as technologists and society learn more about generative AI and its uses and limitations, new science and new policies are already being created to address those challenges.

For toxicity and fairness, careful curation of training data can provide some improvements. After all, if the data doesn’t contain any offensive or biased words or phrases, an LLM simply won’t be able to generate them. But this approach requires that we identify those offensive phrases in advance and are certain that there are absolutely no contexts in which we would want them in the output. Use-case-specific testing can also help address fairness concerns — for instance, before generative AI is used in high-risk domains such as consumer lending, the model could be tested for fairness for that particular application, much as we might do for more narrow predictive models.

For less targeted notions of toxicity, a natural approach is to train what we might call guardrail models that detect and filter out unwanted content in the training data, in input prompts, and in generated outputs. Such models require human-annotated training data in which varying types and degrees of toxicity or bias are identified, which the model can generalize from. In general, it is easier to control the output of a generative model than it is to curate the training data and prompts, given the extreme generality of the tasks we intend to address.

For the challenge of producing high-fidelity content free of hallucinations, an important first step is to educate users about how generative AI actually works, so there is no expectation that the citations or news-like stories produced are always genuine or factually correct. Indeed, some current LLMs, when pressed on their inability to quote actual citations, will tell the user that they are just language models that don’t verify their content with external sources. Such disclaimers should be more frequent and clear. And the specific case of hallucinated citations could be mitigated by augmenting LLMs with independent, verified citation databases and similar sources, using approaches such as retrieval-augmented generation. Another nascent but intriguing approach is to develop methods for attributing generated outputs to particular pieces of training data, allowing users to assess the validity of those sources. This could help with explainability as well.

Concerns around intellectual property are likely to be addressed over time by a mixture of technology, policy, and legal mechanisms. In the near term, science is beginning to emerge around various notions of model disgorgement, in which protected content or its effects on generative outputs are reduced or removed. One technology that might eventually prove relevant is differential privacy, in which a model is trained in a way that ensures that any particular piece of training data has negligible effects on the outputs the model subsequently produces.

Another approach is so-called sharding approaches, which divide the training data into smaller portions on which separate submodels are trained; the submodels are then combined to form the overall model. In order to undo the effects of any particular item of data on the overall model, we need only remove it from its shard and retrain that submodel, rather than retraining the entire model (which for generative AI would be sufficiently expensive as to be prohibitive).

Finally, we can consider filtering or blocking approaches, where before presentation to the user, generated content is explicitly compared to protected content in the training data or elsewhere and suppressed (or replaced) if it is too similar. Limiting the number of times any specific piece of content appears in the training data also proves helpful in reducing verbatim outputs.

Some interesting approaches to discouraging cheating using generative AI are already under development. One is to simply train a model to detect whether a given (say) text was produced by a human or by a generative model. A potential drawback is that this creates an arms race between detection models and generative AI, and since the purpose of generative AI is to produce high-quality content plausibly generated by a human, it’s not clear that detection methods will succeed in the long run.

An intriguing alternative is watermarking or fingerprinting approaches that would be implemented by the developers of generative models themselves. For example, since at each step LLMs are drawing from the distribution over the next word given the text so far, we can divide the candidate words into “red” and “green” lists that are roughly 50% of the probability each; then we can have the LLM draw only from the green list. Since the words on the green list are not known to users, the likelihood that a human would produce a 10-word sentence that also drew only from the green lists is ½ raised to the 10th power, which is only about 0.0009. In this way we can view all-green content as providing a virtual proof of LLM generation. Note that the LLM developers would need to provide such proofs or certificates as part of their service offering.

Disruption to work as we know it does not have any obvious technical defenses, and opinions vary widely on where things will settle. Clearly, generative AI could be an effective productivity tool in many professional settings, and this will at a minimum alter the current division of labor between humans and machines. It’s also possible that the technology will open up existing occupations to a wider community (a recent and culturally specific but not entirely ludicrous quip on social media was “English is the new programming language”, a nod to LLM code generation abilities) or even create new forms of employment, such as prompt engineer (a topic with its own Wikipedia entry, created in just February of this year).

But perhaps the greatest defense against concerns over generative AI may come from the eventual specialization of use cases. Right now, generative AI is being treated as a fascinating, open-ended playground in which our expectations and goals are unclear. As we have discussed, this open-endedness and the plethora of possible uses are major sources of the challenges to responsible AI I have outlined.

But soon more applied and focused uses will emerge, like some of those I suggested earlier. For instance, consider using an LLM as a virtual focus group — creating prompts that describe hypothetical individuals and their demographic properties (age, gender, occupation, location, etc.) and then asking the LLM which of two described products they might prefer.

In this application, we might worry much less about censoring content and much more about removing any even remotely toxic output. And we might choose not to eradicate the correlations between gender and the affinity for certain products in service of fairness, since such correlations are valuable to the marketer. The point is that the more specific our goals for generative AI are, the easier it is to make sensible context-dependent choices; our choices become more fraught and difficult when our expectations are vague.

Finally, we note that end user education and training will play a crucial role in the productive and safe use of generative AI. As the potential uses and harms of generative AI become better and more widely understood, users will augment some of the defenses I have outlined above with their own common sense.

Conclusion

Generative AI has stoked both legitimate enthusiasm and legitimate fears. I have attempted to partially survey the landscape of concerns and to propose forward-looking approaches for addressing them. It should be emphasized that addressing responsible-AI risks in the generative age will be an iterative process: there will be no “getting it right” once and for all. This landscape is sure to shift, with changes to both the technology and our attitudes toward it; the only constant will be the necessity of balancing the enthusiasm with practical and effective checks on the concerns.

Events & Conferences

Revolutionizing warehouse automation with scientific simulation

Modern warehouses rely on complex networks of sensors to enable safe and efficient operations. These sensors must detect everything from packages and containers to robots and vehicles, often in changing environments with varying lighting conditions. More important for Amazon, we need to be able to detect barcodes in an efficient way.

The Amazon Robotics ID (ARID) team focuses on solving this problem. When we first started working on it, we faced a significant bottleneck: optimizing sensor placement required weeks or months of physical prototyping and real-world testing, severely limiting our ability to explore innovative solutions.

To transform this process, we developed Sensor Workbench (SWB), a sensor simulation platform built on NVIDIA’s Isaac Sim that combines parallel processing, physics-based sensor modeling, and high-fidelity 3-D environments. By providing virtual testing environments that mirror real-world conditions with unprecedented accuracy, SWB allows our teams to explore hundreds of configurations in the same amount of time it previously took to test just a few physical setups.

Camera and target selection/positioning

Sensor Workbench users can select different cameras and targets and position them in 3-D space to receive real-time feedback on barcode decodability.

Three key innovations enabled SWB: a specialized parallel-computing architecture that performs simulation tasks across the GPU; a custom CAD-to-OpenUSD (Universal Scene Description) pipeline; and the use of OpenUSD as the ground truth throughout the simulation process.

Parallel-computing architecture

Our parallel-processing pipeline leverages NVIDIA’s Warp library with custom computation kernels to maximize GPU utilization. By maintaining 3-D objects persistently in GPU memory and updating transforms only when objects move, we eliminate redundant data transfers. We also perform computations only when needed — when, for instance, a sensor parameter changes, or something moves. By these means, we achieve real-time performance.

Visualization methods

Sensor Workbench users can pick sphere- or plane-based visualizations, to see how the positions and rotations of individual barcodes affect performance.

This architecture allows us to perform complex calculations for multiple sensors simultaneously, enabling instant feedback in the form of immersive 3-D visuals. Those visuals represent metrics that barcode-detection machine-learning models need to work, as teams adjust sensor positions and parameters in the environment.

CAD to USD

Our second innovation involved developing a custom CAD-to-OpenUSD pipeline that automatically converts detailed warehouse models into optimized 3-D assets. Our CAD-to-USD conversion pipeline replicates the structure and content of models created in the modeling program SolidWorks with a 1:1 mapping. We start by extracting essential data — including world transforms, mesh geometry, material properties, and joint information — from the CAD file. The full assembly-and-part hierarchy is preserved so that the resulting USD stage mirrors the CAD tree structure exactly.

To ensure modularity and maintainability, we organize the data into separate USD layers covering mesh, materials, joints, and transforms. This layered approach ensures that the converted USD file faithfully retains the asset structure, geometry, and visual fidelity of the original CAD model, enabling accurate and scalable integration for real-time visualization, simulation, and collaboration.

OpenUSD as ground truth

The third important factor was our novel approach to using OpenUSD as the ground truth throughout the entire simulation process. We developed custom schemas that extend beyond basic 3-D-asset information to include enriched environment descriptions and simulation parameters. Our system continuously records all scene activities — from sensor positions and orientations to object movements and parameter changes — directly into the USD stage in real time. We even maintain user interface elements and their states within USD, enabling us to restore not just the simulation configuration but the complete user interface state as well.

This architecture ensures that when USD initial configurations change, the simulation automatically adapts without requiring modifications to the core software. By maintaining this live synchronization between the simulation state and the USD representation, we create a reliable source of truth that captures the complete state of the simulation environment, allowing users to save and re-create simulation configurations exactly as needed. The interfaces simply reflect the state of the world, creating a flexible and maintainable system that can evolve with our needs.

Application

With SWB, our teams can now rapidly evaluate sensor mounting positions and verify overall concepts in a fraction of the time previously required. More importantly, SWB has become a powerful platform for cross-functional collaboration, allowing engineers, scientists, and operational teams to work together in real time, visualizing and adjusting sensor configurations while immediately seeing the impact of their changes and sharing their results with each other.

New perspectives

In projection mode, an explicit target is not needed. Instead, Sensor Workbench uses the whole environment as a target, projecting rays from the camera to identify locations for barcode placement. Users can also switch between a comprehensive three-quarters view and the perspectives of individual cameras.

Due to the initial success in simulating barcode-reading scenarios, we have expanded SWB’s capabilities to incorporate high-fidelity lighting simulations. This allows teams to iterate on new baffle and light designs, further optimizing the conditions for reliable barcode detection, while ensuring that lighting conditions are safe for human eyes, too. Teams can now explore various lighting conditions, target positions, and sensor configurations simultaneously, gleaning insights that would take months to accumulate through traditional testing methods.

Looking ahead, we are working on several exciting enhancements to the system. Our current focus is on integrating more-advanced sensor simulations that combine analytical models with real-world measurement feedback from the ARID team, further increasing the system’s accuracy and practical utility. We are also exploring the use of AI to suggest optimal sensor placements for new station designs, which could potentially identify novel configurations that users of the tool might not consider.

Additionally, we are looking to expand the system to serve as a comprehensive synthetic-data generation platform. This will go beyond just simulating barcode-detection scenarios, providing a full digital environment for testing sensors and algorithms. This capability will let teams validate and train their systems using diverse, automatically generated datasets that capture the full range of conditions they might encounter in real-world operations.

By combining advanced scientific computing with practical industrial applications, SWB represents a significant step forward in warehouse automation development. The platform demonstrates how sophisticated simulation tools can dramatically accelerate innovation in complex industrial systems. As we continue to enhance the system with new capabilities, we are excited about its potential to further transform and set new standards for warehouse automation.

Events & Conferences

Enabling Kotlin Incremental Compilation on Buck2

The Kotlin incremental compiler has been a true gem for developers chasing faster compilation since its introduction in build tools. Now, we’re excited to bring its benefits to Buck2 – Meta’s build system – to unlock even more speed and efficiency for Kotlin developers.

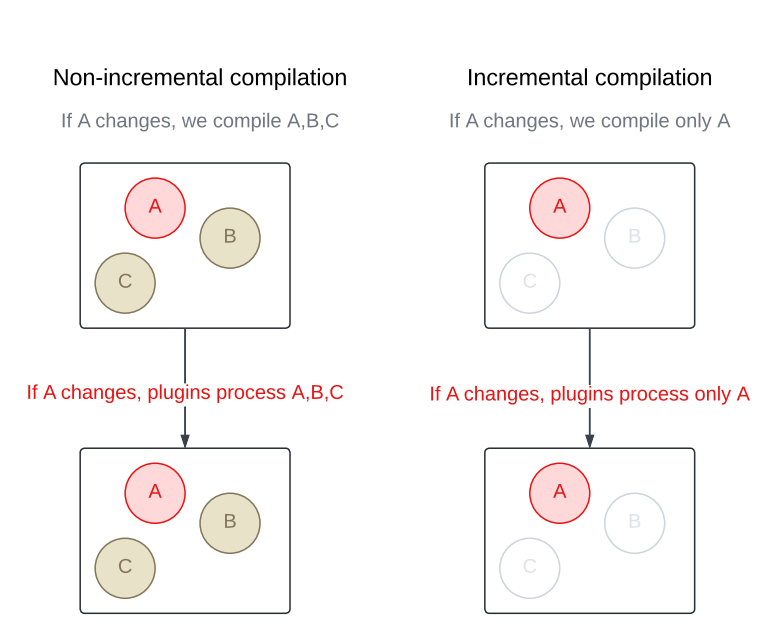

Unlike a traditional compiler that recompiles an entire module every time, an incremental compiler focuses only on what was changed. This cuts down compilation time in a big way, especially when modules contain a large number of source files.

Buck2 promotes small modules as a key strategy for achieving fast build times. Our codebase followed that principle closely, and for a long time, it worked well. With only a handful of files in each module, and Buck2’s support for fast incremental builds and parallel execution, incremental compilation didn’t seem like something we needed.

But, let’s be real: Codebases grow, teams change, and reality sometimes drifts away from the original plan. Over time, some modules started getting bigger – either from legacy or just organic growth. And while big modules were still the exception, they started having quite an impact on build times.

So we gave the Kotlin incremental compiler a closer look – and we’re glad we did. The results? Some critical modules now build up to 3x faster. That’s a big win for developer productivity and overall build happiness.

Curious about how we made it all work in Buck2? Keep reading. We’ll walk you through the steps we took to bring the Kotlin incremental compiler to life in our Android toolchain.

Step 1: Integrating Kotlin’s Build Tools API

As of Kotlin 2.2.0, the only guaranteed public contract to use the compiler is through the command-line interface (CLI). But since the CLI doesn’t support incremental compilation (at least for now), it didn’t meet our needs. Alternatively, we could integrate the Kotlin incremental compiler directly via the internal compiler’s components – APIs that are technically accessible but not intended for public use. However, relying on them would’ve made our toolchain fragile and likely to break with every Kotlin update since there’s no guarantee of backward compatibility. That didn’t seem like the right path either.

Then we came across the Build Tools API (KEEP), introduced in Kotlin 1.9.20 as the official integration point for the compiler – including support for incremental compilation. Although the API was still marked as experimental, we decided to give it a try. We knew it would eventually stabilize, and saw it as a great opportunity to get in early, provide feedback, and help shape its direction. Compared to using internal components, it offered a far more sustainable and future-proof approach to integration.

⚠️ Depending on kotlin-compiler? Watch out!

In the Java world, a shaded library is a modified version of the library where the class and package names are changed. This process – called shading – is a handy way to avoid classpath conflicts, prevent version clashes between libraries, and keeps internal details from leaking out.

Here’s quick example:

- Unshaded (original) class: com.intellij.util.io.DataExternalizer

- Shaded class: org.jetbrains.kotlin.com.intellij.util.io.DataExternalizer

The Build Tools API depends on the shaded version of the Kotlin compiler (kotlin-compiler-embeddable). But our Android toolchain was historically built with the unshaded one (kotlin-compiler). That mismatch led to java.lang.NoClassDefFoundError crashes when testing the integration because the shaded classes simply weren’t on the classpath.

Replacing the unshaded compiler across the entire Android toolchain would’ve been a big effort. So to keep moving forward, we went with a quick workaround: We unshaded the Build Tools API instead. 🙈 Using the jarjar library, we stripped the org.jetbrains.kotlin prefix from class names and rebuilt the library.

Don’t worry, once we had a working prototype and confirmed everything behaved as expected, we circled back and did it right – fully migrating our toolchain to use the shaded Kotlin compiler. That brought us back in line with the API’s expectations and gave us a more stable setup for the future.

Step 2: Keeping previous output around for the incremental compiler

To compile incrementally, the Kotlin compiler needs access to the output from the previous build. Simple enough, but Buck2 deletes that output by default before rebuilding a module.

With incremental actions, you can configure Buck2 to skip the automatic cleanup of previous outputs. This gives your build actions access to everything from the last run. The tradeoff is that it’s now up to you to figure out what’s still useful and manually clean up the rest. It’s a bit more work, but it’s exactly what we needed to make incremental compilation possible.

Step 3: Making the incremental compiler cache relocatable

At first, this might not seem like a big deal. You’re not planning to move your codebase around, so why worry about making the cache relocatable, right?

Well… that’s until you realize you’re no longer in a tiny team, and you’re definitely not the only one building the project. Suddenly, it does matter.

Buck2 supports distributed builds, which means your builds don’t have to run only on your local machine. They can be executed elsewhere, with the results sent back to you. And if your compiler cache isn’t relocatable, this setup can quickly lead to trouble – from conflicting overloads to strange ambiguity errors caused by mismatched paths in cached data.

So we made sure to configure the root project directory and the build directory explicitly in the incremental compilation settings. This keeps the compiler cache stable and reliable, no matter who runs the build or where it happens.

Step 4: Configuring the incremental compiler

In a nutshell, to decide what needs to be recompiled, the Kotlin incremental compiler looks for changes in two places:

- Files within the module being rebuilt.

- The module’s dependencies.

Once the changes are found, the compiler figures out which files in the module are affected – whether by direct edits or through updated dependencies – and recompiles only those.

To get this process rolling, the compiler needs just a little nudge to understand how much work it really has to do.

So let’s give it that nudge!

Tracking changes inside the module

When it comes to tracking changes, you’ve got two options: You can either let the compiler do its magic and detect changes automatically, or you can give it a hand by passing a list of modified files yourself. The first option is great if you don’t know which files have changed or if you just want to get something working quickly (like we did during prototyping). However, if you’re on a Kotlin version earlier than 2.1.20, you have to provide this information yourself. Automatic source change detection via the Build Tools API isn’t available prior to that. Even with newer versions, if the build tool already has the change list before compilation, it’s still worth using it to optimize the process.

This is where Buck’s incremental actions come in handy again! Not only can we preserve the output from the previous run, but we also get hash digests for every action input. By comparing those hashes with the ones from the last build, we can generate a list of changed files. From there, we pass that list to the compiler to kick off incremental compilation right away – no need for the compiler to do any change detection on its own.

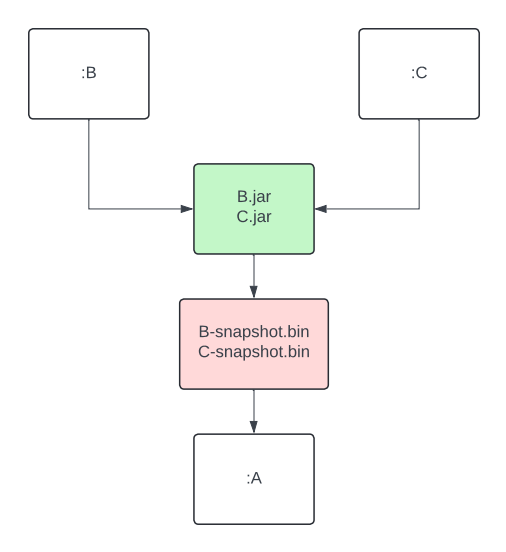

Tracking changes in dependencies

Sometimes it’s not the module itself that changes, it’s something the module depends on. In these cases, the compiler relies on classpath snapshot. These snapshots capture the Application Binary Interface (ABI) of a library. By comparing the current snapshots to the previous one, the compiler can detect changes in dependencies and figure out which files in your module are affected. This adds an extra layer of filtering on top of standard compilation avoidance.

In Buck2, we added a dedicated action to generate classpath snapshots from library outputs. This artifact is then passed as an input to the consuming module, right alongside the library’s compiled output. The best part? Since it’s a separate action, it can be run remotely or be pulled from cache, so your machine doesn’t have to do the heavy lifting of extracting ABI at this step.

If, after all, only your module changes but your dependencies do not, the API also lets you skip the snapshot comparison entirely if your build tool handles the dependency analysis on its own. Since we already had the necessary data from Buck2’s incremental actions, adding this optimization was almost free.

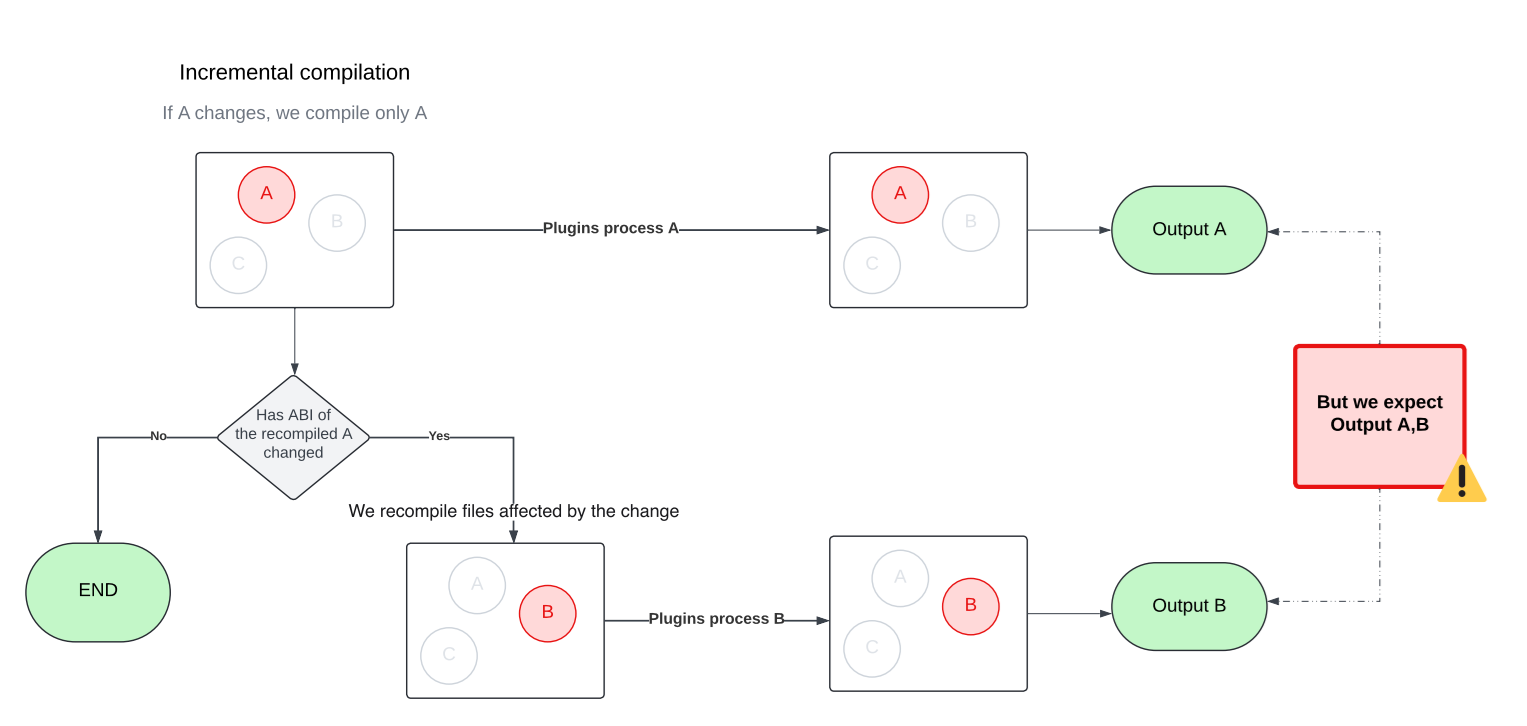

Step 5: Making compiler plugins work with the incremental compiler

One of the biggest challenges we faced when integrating the incremental compiler was making it play nicely with our custom compiler plugins, many of which are important to our build optimization strategy. This step was necessary for unlocking the full performance benefits of incremental compilation, but it came with two major issues we needed to solve.

🚨 Problem 1: Incomplete results

As we already know, the input to the incremental compiler does not have to include all Kotlin source files. Our plugins weren’t designed for this and ended up producing incomplete results when run on just a subset of files. We had to make them incremental as well so they could handle partial inputs correctly.

🚨 Problem 2: Multiple rounds of Compilation

The Kotlin incremental compiler doesn’t just recompile the files that changed in a module. It may also need to recompile other files in the same module that are affected by those changes. Figuring out the exact set of affected files is tricky, especially when circular dependencies come into play. To handle this, the incremental compiler approximates the affected set by compiling in multiple rounds within a single build.

💡Curious how that works under the hood? The Kotlin blog on fast compilation has a great deep dive that’s worth checking out.

This behavior comes with a side effect, though. Since the compiler may run in multiple rounds with different sets of files, compiler plugins can also be triggered multiple times, each time with a different input. That can be problematic, as later plugin runs may override outputs produced by earlier ones. To avoid this, we updated our plugins to accumulate their results across rounds rather than replacing them.

Step 6: Verifying the functionality of annotation processors

Most of our annotation processors use Kotlin Symbol Processing (KSP2), which made this step pretty smooth. KSP2 is designed as a standalone tool that uses the Kotlin Analysis API to analyze source code. Unlike compiler plugins, it runs independently from the standard compilation flow. Thanks to this setup, we were able to continue using KSP2 without any changes.

💡 Bonus: KSP2 comes with its own built-in incremental processing support. It’s fully self-contained and doesn’t depend on the incremental compiler at all.

Before we adopted KSP2 (or when we were using an older version of the Kotlin Annotation Processing Tool (KAPT), which operates as a plugin) our annotation processors ran in a separate step dedicated solely to annotation processing. That step ran before the main compilation and was always non-incremental.

Step 7: Enabling compilation against ABI

To maximize cache hits, Buck2 builds Android modules against the class ABI instead of the full JAR. For Kotlin targets, we use the jvm-abi-gen compiler plugin to generate class ABI during compilation.

But once we turned on incremental compilation, a couple of new challenges popped up:

- The jvm-abi-gen plugin currently lacks direct support for incremental compilation, which ties back to the issues we mentioned earlier with compiler plugins.

- ABI extraction now happens twice – once during compilation via jvm-abi-gen, and again when the incremental compiler creates classpath snapshots.

In theory, both problems could be solved by switching to full JAR compilation and relying on classpath snapshots to maintain cache hits. While that could work in principle, it would mean giving up some of the build optimizations we’ve already got in place – a trade-off that needs careful evaluation before making any changes.

For now, we’ve implemented a custom (yet suboptimal) solution that merges the newly generated ABI with the previous result. It gets the job done, but we’re still actively exploring better long-term alternatives.

Ideally, we’d be able to reuse the information already collected for classpath snapshot or, even better, have this kind of support built directly into the Kotlin compiler. There’s an open ticket for that: KT-62881. Fingers crossed!

Step 8: Testing

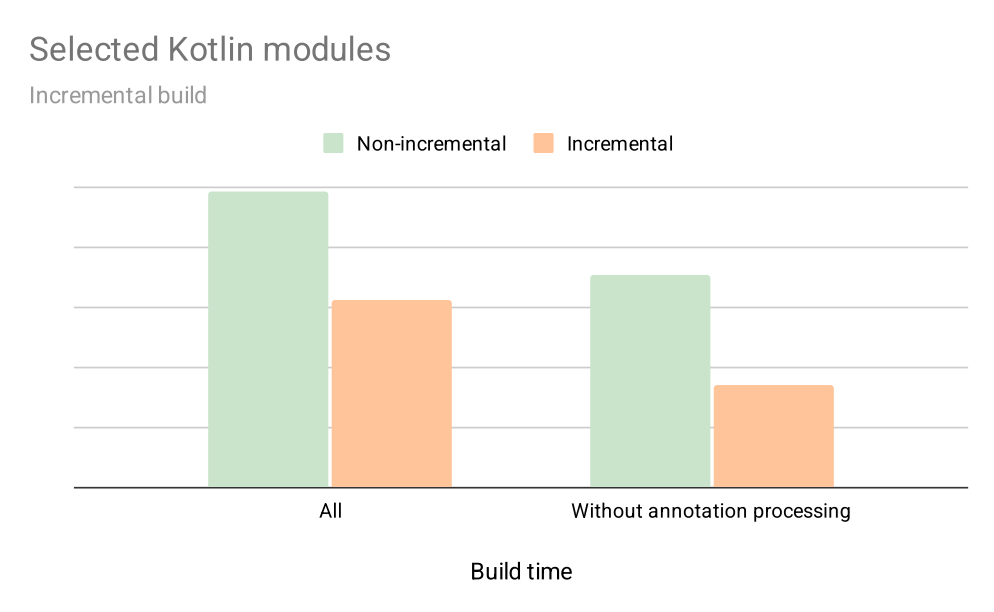

Measuring the impact of build changes is not an easy task. Benchmarking is great for getting a sense of a feature’s potential, but it doesn’t always reflect how things perform in “the real world.” Pre/post testing can help with that, but it’s tough to isolate the impact of a single change, especially when you’re not the only one pushing code.

We set up A/B testing to overcome these obstacles and measure the true impact of the Kotlin incremental compiler on Meta’s codebase with high confidence. It took a bit of extra work to keep the cache healthy across variants, but it gave us a clean, isolated view of how much difference the incremental compiler really made at scale.

We started with the largest modules – the ones we already knew were slowing builds the most. Given their size and known impact, we expected to see benefits quickly. And sure enough, we did.

The impact of incremental compilation

The graph below shows early results on how enabling incremental compilation for selected targets impacts their local build times during incremental builds over a 4-week period. This includes not just compilation, but also annotation processing, and a few other optimisations we’ve added along the way.

With incremental compilation, we’ve seen about a 30% improvement for the average developer. And for modules without annotation processing, the speed nearly doubled. That was more than enough to convince us that the incremental compiler is here to stay.

What’s next

Kotlin incremental compilation is now supported in Buck2, and we’re actively rolling it out across our codebase! For now, it’s available for internal use only, but we’re working on bringing it to the recently introduced open source toolchain as well.

But that’s not all! We’re also exploring ways to expand incrementality across the entire Android toolchain, including tools like Kosabi (the Kotlin counterpart to Jasabi), to deliver even faster build times and even better developer experience.

To learn more about Meta Open Source, visit our open source site, subscribe to our YouTube channel, or follow us on Facebook, Threads, X and LinkedIn.

Events & Conferences

A decade of database innovation: The Amazon Aurora story

When Andy Jassy, then head of Amazon Web Services, announced Amazon Aurora in 2014, the pitch was bold but metered: Aurora would be a relational database built for the cloud. As such, it would provide access to cost-effective, fast, and scalable computing infrastructure.

In essence, he explained, Aurora would combine the cost effectiveness and simplicity of MySQL with the speed and availability of high-end commercial databases, the kind that firms typically managed on their own. In numbers, Aurora promised five times the throughput (e.g., the number of transactions, queries, read/write operations) of MySQL at one-tenth the price of commercial database solutions, all while offloading costly management challenges and maintaining performance and availability.

AWS re:Invent 2014 | Announcing Amazon Aurora for RDS

Aurora launched a year later, in 2015. Significantly, it decoupled computation from storage, a distinct contrast to traditional database architectures where the two are entwined. This fundamental innovation, along with automated backups and replication and other improvements, enabled easy scaling for both computational tasks and storage, while meeting reliability demands.

“Aurora’s design preserves the core transactional consistency strengths of relational databases. It innovates at the storage layer to create a database built for the cloud that can support modern workloads without sacrificing performance,” explained Werner Vogels, Amazon’s CTO, in 2019.

“To start addressing the limitations of relational databases, we reconceptualized the stack by decomposing the system into its fundamental building blocks,” Vogels said. “We recognized that the caching and logging layers were ripe for innovation. We could move these layers into a purpose-built, scale-out, self-healing, multitenant, database-optimized storage service. When we began building the distributed storage system, Amazon Aurora was born.”

Within two years, Aurora became the fastest-growing service in AWS history. Tens of thousands of customers — including financial-services companies, gaming companies, healthcare providers, educational institutions, and startups — turned to Aurora to help carry their workloads.

In the intervening years, Aurora has continued to evolve to suit the needs of a changing digital landscape. Most recently, in 2024, Amazon announced Aurora DSQL. A major step forward, Aurora DSQL is a serverless approach designed for global scale and enhanced adaptability to variable workloads.

Today, International Data Corporation (IDC) research estimates that firms using Aurora see a three-year return on investment of 434 percent and an operational cost reduction of 42 percent compared to other database solutions.

But what lies behind those figures? How did Aurora become so valuable to its users? To understand that, it’s useful to consider what came before.

A time for reinvention

In 2015, as cloud computing was gaining popularity, legacy firms began migrating workloads away from on-premises data centers to save money on capital investments and in-house maintenance. At the same time, mobile and web app startups were calling for remote, highly reliable databases that could scale in an instant. The theme was clear: computing and storage needed to be elastic and reliable. The reality was that, at the time, most databases simply hadn’t adapted to those needs.

Amazon engineers recognized that the cloud could enable virtually unlimited, networked storage and, separately, compute.

That rigidity makes sense considering the origin of databases and the problems they were invented to solve. The 1960s saw one of their earliest uses: NASA engineers had to navigate a complex list of parts, components, and systems as they built spacecraft for moon exploration. That need inspired the creation of the Information Management System, or IMS, a hierarchically structured solution that allowed engineers to more easily locate relevant information, such as the sizes or compatibilities of various parts and components. While IMS was a boon at the time, it was also limited. Finding parts meant engineers had to write batches of specially coded queries that would then move through a tree-like data structure, a relatively slow and specialized process.

In 1970, the idea of relational databases made its public debut when E. F. Codd coined the term. Relational databases organized data according to how it was related: customers and their purchases, for instance, or students in a class. Relational databases meant faster search, since data was stored in structured tables, and queries didn’t require special coding knowledge. With programming languages like SQL, relational databases became a dominant model for storing and retrieving structured data.

By the 1990s, however, that approach began to show its limits. Firms that needed more computing capabilities typically had to buy and physically install more on-premises servers. They also needed specialists to manage new capabilities, such as the influx of transactional workloads — as, for instance, when increasing numbers of customers added more and more pet supplies to virtual shopping carts. By the time AWS arrived in 2006, these legacy databases were the most brittle, least elastic component of a company’s IT stack.

The emergence of cloud computing promised a better way forward with more flexibility and remotely managed solutions. Amazon engineers recognized that the cloud could enable virtually unlimited, networked storage and, separately, computation.

The Amazon Relational Database Service (Amazon RDS) debuted in 2009 to help customers set up, operate, and scale a MySQL database in the cloud. And while that service expanded to include Oracle, SQL Server, and PostgreSQL, as Jeff Barr noted in a 2014 blog post, those database engines “were designed to function in a constrained and somewhat simplistic hardware environment.”

AWS researchers challenged themselves to examine those constraints and “quickly realized that they had a unique opportunity to create an efficient, integrated design that encompassed the storage, network, compute, system software, and database software”.

“The central constraint in high-throughput data processing has moved from compute and storage to the network,” wrote the authors of a SIGMOD 2017 paper describing Aurora’s architecture. Aurora researchers addressed that constraint via “a novel, service-oriented architecture”, one that offered significant advantages over traditional approaches. These included “building storage as an independent fault-tolerant and self-healing service across multiple data centers … protecting databases from performance variance and transient or permanent failures at either the networking or storage tiers.”’

The serverless era is now

In the years since its debut, Amazon engineers and researchers have ensured Aurora has kept pace with customer needs. In 2018, Aurora Serverless provided an on-demand autoscaling configuration that allowed customers to adjust computational capacity up and down based on their needs. Later versions further optimized that process by automatically scaling based on customer needs. That approach relieves the customer of the need to explicitly manage database capacity; customers need to specify only minimum and maximum levels.

Achieving that sort of “resource elasticity at high levels of efficiency” meant Aurora Serverless had to address several challenges, wrote the authors of a VLDB 2024 paper. “These included policy issues such as how to define ‘heat’ (i.e., resource usage features on which to base decision making)” and how to determine whether remedial action may be required. Aurora Serverless meets those challenges, the authors noted, by adapting and modifying “well-established ideas related to resource oversubscription; reactive control informed by recent measurements; distributed and hierarchical decision making; and innovations in the DB engine, OS, and hypervisor for efficiency.”

As of May 2025, all of Aurora’s offerings are now serverless. Customers no longer need to choose a specific server type or size or worry about the underlying hardware or operating system, patching, or backups; all that is completely managed by AWS. “One of the things that we’ve tried to design from the beginning is a database where you don’t have to worry about the internals,” Marc Brooker, AWS vice president and Distinguished Engineer, said at AWS re:Invent in 2024.

These are exactly the capabilities that Arizona State University needs, says John Rome, deputy chief information officer at ASU. Each fall, the university’s data needs explode when classes for its more than 73,000 students are in session across multiple campuses. Aurora lets ASU pay for the computation and storage it uses and helps it to adapt on the fly.

We see Amazon Aurora Serverless as a next step in our cloud maturity.

John Rome, deputy chief information officer at ASU

“We see Amazon Aurora Serverless as a next step in our cloud maturity,” Rome says, “to help us improve development agility while reducing costs on infrequently used systems, to further optimize our overall infrastructure operations.”

And what might the next step in maturity look like for the now 10-year-old Aurora service? The authors of that 2024 paper outlined several potential paths. Those include “introducing predictive techniques for live migration”; “exploiting statistical multiplexing opportunities stemming from complementary resource needs”, and “using sophisticated ML/RL-based techniques for workload prediction and decision making.”

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences3 months ago

Events & Conferences3 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoAstrophel Aerospace Raises ₹6.84 Crore to Build Reusable Launch Vehicle

-

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months ago

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months agoDonald Trump suggests US government review subsidies to Elon Musk’s companies