Education

Record proportion of A-level students get top grades in England | A-levels

Students in England gained record levels of top grades in this year’s A-level exams, driven by young men producing their strongest performances outside the pandemic years.

Ofqual, the exam regulator for England, shrugged off any suggestions of grade inflation, pointing to the lower proportion of 18-year-olds taking A-levels and saying that fewer low-achieving students had entered.

Despite the overall improvement, regional variations remain, with students in the West Midlands and north-east England recording lower grades overall than in 2024. The north-east remains the only region of England with average grades below pre-pandemic levels.

Among the more than 1.1m entries in England, 28.2% gained an A or A* grade, while 9.4% gained the top A* grade, both higher than in 2024 when 27.6% of entries got A and A*s and 9.3% gained A*s.

Across all students in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 28.3% of entries were awarded an A or A* grade, up by 0.5 percentage points on last year. Wales was the only country of the three to see a drop in the proportion of top grades awarded compared with last year, falling from 29.9% to 29.5%.

Other than in 2020, 2021 and 2022, when awards were affected by changes to assessments caused by Covid-19, the proportion of top grades in England was higher than any year since the A* grade was introduced in 2010, and before that going back to 2001.

Ian Bauckham, Ofqual’s chief regulator responsible for England’s results, said: “Standards have been maintained for another year, with grades determined by students’ performance in exams using exam boards’ strict marking and grading processes.”

Bauckham noted that the number of entries were down compared with last year, despite the increased numbers of 18-year-olds in the population, and said a “smaller, smarter cohort” was taking A-levels this year.

“This may be a sign that young people are making different choices about what types of qualification suit them, which then has an impact on A-level outcomes,” Bauckham said.

Young men outpaced young women in the proportion of entries with the two top grades, with 28.4% compared with 28% for women in England, reversing the positions of previous years. The improved performance – which belies recent complaints of boys being “left behind” by the school system – was more extreme among sixth-formers, where 9.9% of entries by male students gained A*s compared with 9.1% for female students.

The gap between the highest- and lowest-performing regions widened further, with 32.1% of entries in London gaining A* or A, compared with 22.9% in north-east England.

Jill Duffy, the chief executive of the OCR examination board, said: “Regional inequalities are getting worse, not better. The gap at top grades [A* or A] has grown again. London is once again the top-performing region and is now 9.2 percentage points ahead of the north-east.

“The north-east is the only region in England where the proportion of A* and A grades is down on both last year and 2019. The picture is slightly brighter at A*-C, with a smaller gap between regions. These regional inequalities need more attention.”

The Ucas university admissions administrator said record numbers of 18-year-olds in the UK got a place at university or college for this autumn. The A-level, BTec and T-level results showed 255,130 had been accepted, compared to 243,650 in 2024, a rise of 4.7%.

Education

Nation’s Report Card at risk, researchers say

This story was reported by and originally published by APM Reports in connection with its podcast Sold a Story: How Teach Kids to Read Went So Wrong.

When voters elected Donald Trump in November, most people who worked at the U.S. Department of Education weren’t scared for their jobs. They had been through a Trump presidency before, and they hadn’t seen big changes in their department then. They saw their work as essential, mandated by law, nonpartisan and, as a result, insulated from politics.

Then, in early February, the Department of Government Efficiency showed up. Led at the time by billionaire CEO Elon Musk, and known by the cheeky acronym DOGE, it gutted the Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences, posting on X that the effort would ferret out “waste, fraud and abuse.”

A post from the Department of Government Efficiency.

When it was done, DOGE had cut approximately $900 million in research contracts and more than 90 percent of the institute’s workforce had been laid off. (The current value of the contracts was closer to $820 million, data compiled by APM Reports shows, and the actual savings to the government was substantially less, because in some cases large amounts of money had been spent already.)

Among staff cast aside were those who worked on the National Assessment of Educational Progress — also known as the Nation’s Report Card — which is one of the few federal education initiatives the Trump administration says it sees as valuable and wants to preserve.

The assessment is a series of tests administered nearly every year to a national sample of more than 10,000 students in grades 4, 8 and 12. The tests regularly measure what students across the country know in reading, math and other subjects. They allow the government to track how well America’s students are learning overall. Researchers can also combine the national data with the results of tests administered by states to draw comparisons between schools and districts in different states.

The assessment is “something we absolutely need to keep,” Education Secretary Linda McMahon said at an education and technology summit in San Diego earlier this year. “If we don’t, states can be a little manipulative with their own results and their own testing. I think it’s a way that we keep everybody honest.”

But researchers and former Department of Education employees say they worry that the test will become less and less reliable over time, because the deep cuts will cause its quality to slip — and some already see signs of trouble.

“The main indication is that there just aren’t the staff,” said Sean Reardon, a Stanford University professor who uses the testing data to research gaps in learning between students of different income levels.

All but one of the experts who make sure the questions in the assessment are fair and accurate — called psychometricians — have been laid off from the National Center for Education Statistics. These specialists play a key role in updating the test and making sure it accurately measures what students know.

“These are extremely sophisticated test assessments that required a team of researchers to make them as good as they are,” said Mark Seidenberg, a researcher known for his significant contributions to the science of reading. Seidenberg added that “a half-baked” assessment would undermine public confidence in the results, which he described as “essentially another way of killing” the assessment.

The Department of Education defended its management of the assessment in an email: “Every member of the team is working toward the same goal of maintaining NAEP’s gold-standard status,” it read in part.

The National Assessment Governing Board, which sets policies for the national test, said in a statement that it had temporarily assigned “five staff members who have appropriate technical expertise (in psychometrics, assessment operations, and statistics) and federal contract management experience” to work at the National Center for Education Statistics. No one from DOGE responded to a request for comment.

Harvard education professor Andrew Ho, a former member of the governing board, said the remaining staff are capable, but he’s concerned that there aren’t enough of them to prevent errors.

“In order to put a good product up, you need a certain number of person-hours, and a certain amount of continuity and experience doing exactly this kind of job, and that’s what we lost,” Ho said.

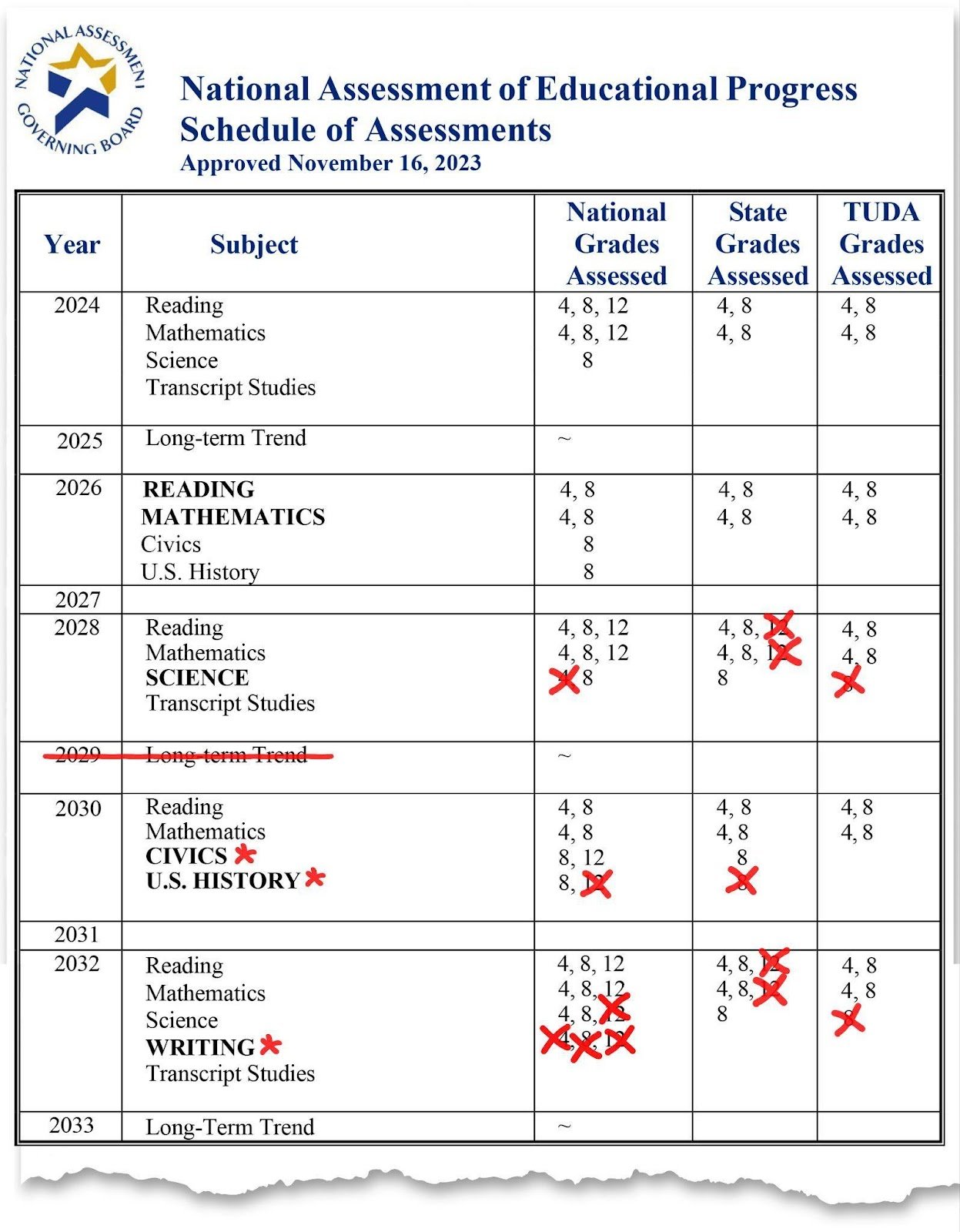

The Trump administration has already delayed the release of some testing data following the cutbacks. The Department of Education had previously planned to announce the results of the tests for 8th grade science, 12th grade math and 12th grade reading this summer; now that won’t happen until September. The board voted earlier this year to eliminate more than a dozen tests over the next seven years, including fourth grade science in 2028 and U.S. history for 12th graders in 2030. The governing board has also asked Congress to postpone the 2028 tests to 2029, citing a desire to avoid releasing test results in an election year.

“Today’s actions reflect what assessments the Governing Board believes are most valuable to stakeholders and can be best assessed by NAEP at this time, given the imperative for cost efficiencies,” board chair and former North Carolina Gov. Bev Perdue said earlier this year in a press release.

Recent estimates peg the annual cost to keep the national assessment running at about $190 million per year, a fraction of the department’s 2025 budget of approximately $195 billion.

Adam Gamoran, president of the William T. Grant Foundation, said multiple contracts with private firms — overseen by Department of Education staff with “substantial expertise” — are the backbone of the national test.

“You need a staff,” said Gamoran, who was nominated last year to lead the Institute of Education Sciences. He was never confirmed by the Senate. “The fact that NCES now only has three employees indicates that they can’t possibly implement NAEP at a high level of quality, because they lack the in-house expertise to oversee that work. So that is deeply troubling.”

The cutbacks were widespread — and far outside of what most former employees had expected under the new administration.

“I don’t think any of us imagined this in our worst nightmares,” said a former Education Department employee, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation by the Trump administration. “We weren’t concerned about the utter destruction of this national resource of data.”

“At what point does it break?” the former employee asked.

Related: Suddenly sacked

Every state has its own test for reading, math and other subjects. But state tests vary in difficulty and content, which makes it tricky to compare results in Minnesota to Mississippi or Montana.

“They’re totally different tests with different scales,” Reardon said. “So NAEP is the Rosetta stone that lets them all be connected.”

Reardon and his team at Stanford used statistical techniques to combine the federal assessment results with state test scores and other data sets to create the Educational Opportunity Project. The project, first released in 2016 and updated periodically in the years that followed, shows which schools and districts are getting the best results — especially for kids from poor families. Since the project’s release, Reardon said, the data has been downloaded 50,000 times and is used by researchers, teachers, parents, school boards and state education leaders to inform their decisions.

For instance, the U.S. military used the data to measure school quality when weighing base closures, and superintendents used it to find demographically similar but higher-performing districts to learn from, Reardon said.

If the quality of the data slips, those comparisons will be more difficult to make.

“My worry is we just have less-good information on which to base educational decisions at the district, state and school level,” Reardon said. “We would be in the position of trying to improve the education system with no information. Sort of like, ‘Well, let’s hope this works. We won’t know, but it sounds like a good idea.’”

Seidenberg, the reading researcher, said the national assessment “provided extraordinarily important, reliable information about how we’re doing in terms of teaching kids to read and how literacy is faring in the culture at large.”

Producing a test without keeping the quality up, Seidenberg said, “would be almost as bad as not collecting the data at all.”

Education

Reimagining Writing in the Age of AI: Challenges and Opportunities for Universities

As a new academic year begins, educators find themselves grappling with the implications of large language models (LLMs) on learning and writing. The technology, which can generate text resembling academic English, raises questions about authorship and the cognitive demands of writing.

Historically, universities have treated writing as an indicator of intelligence, focusing heavily on correctness. However, this perspective overlooks writing’s true purpose as a means for students to develop and articulate ideas. Critics argue that without adapting teaching methods, students risk becoming dependent on AI and disconnected from their own creative capacities.

Experts propose redefining writing assignments, allowing students to submit works-in-progress, and integrating feedback into the learning process. This shift aims to promote originality and critical thinking. Failure to engage writing scholars in AI policy could result in students producing output that mirrors established norms rather than exploring new intellectual territories.

Education

70% of American high schoolers doubt the future value of what they are learning: Will AI make today’s classrooms obsolete?

American classrooms are facing an unprecedented crisis of confidence. According to Discovery Education’s Education Insights 2025–26 report, a striking 70% of high school students believe the skills they’re learning today will soon be replaced by artificial intelligence (AI). This growing skepticism is forcing educators and policymakers to confront unsettling questions: What is the real value of classroom learning in a world increasingly dominated by machines? And how can schools remain relevant when students themselves doubt the future of their education?

Smartphones: The omnipresent distraction

Even before AI entered the picture, technology had already reshaped learning. The Education Insights 2025–26 report, alongside other national surveys, reveals that 97% of high school students use their phones during the school day, with 60% admitting to regular in-class use. Teachers are paying the price: more than 70% say cellphones are a major distraction, undermining focus and performance.Despite widespread school policies restricting phone use—55% of high schools now enforce bans—six in ten teachers say enforcement is ineffective, and nearly half believe that unchecked phone use is harming academic outcomes. Students, meanwhile, continue to use social media apps like TikTok and YouTube during class hours, cutting into participation and in-person interaction.

Artificial Intelligence: Tool or threat?

AI has added a new layer of complexity to the digital classroom. Discovery Education’s findings show that 40% of students admit to using AI for assignments without permission, while 65% of teachers report catching students doing so. With clear policies still lacking, the line between innovation and academic dishonesty has blurred.Yet, students are not entirely cynical. The same report shows that two-thirds of high schoolers believe AI can help them learn faster, and nearly three-quarters have already been allowed to use AI in at least some schoolwork. School leaders are even more optimistic: over 90% of superintendents and principals express enthusiasm about AI’s potential, though only half of teachers share that optimism. Concerns about plagiarism, distraction, and the absence of training weigh heavily on educators.

Existential doubts in the classroom

The 70% figure stands out as perhaps the most alarming finding from the Education Insights 2025–26 report. Students are increasingly convinced that traditional academic skills will not survive the AI revolution. This perception risks deepening disengagement, as teens question whether their time in classrooms is preparing them for meaningful futures.Teachers, meanwhile, are left navigating what knowledge remains essential when algorithms can write essays, solve equations, and generate ideas faster than humans. The fundamental role of schools—as places to impart lasting skills and knowledge—is suddenly under debate.

Policy gaps and uneven responses

Schools are experimenting with responses, from “cellphone hotel” drop-off policies to state-level bans on TikTok across school networks. Some districts are even lobbying social media platforms over their role in harming student mental health. But enforcement remains uneven, and students’ tech-savvy often outpaces school restrictions.AI integration policies are even less developed. While leaders push for innovation, teachers frequently feel underprepared and unsupported. The Education Insights 2025–26 report highlights this gap: enthusiasm at the administrative level has not translated into clear classroom strategies.

The crossroads ahead

The Discovery Education report makes clear that technology is not going away. When used intentionally, digital tools can enhance learning, foster collaboration, and build digital literacy. Many educators report higher engagement when technology is directly tied to instruction. But without urgent and thoughtful strategies, the double-edged sword of smartphones and AI risks deepening distraction, fueling distrust in education, and widening the gap between students’ expectations and schools’ offerings.The ultimate question remains: If most students already believe AI will replace what they are learning, can today’s classrooms adapt fast enough to prove them wrong?

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics