One of the most advanced nuclear fusion developers has raised about $900mn from backers including Nvidia and Morgan Stanley, as it races to complete a demonstration plant in the US and commercialise the nascent energy technology.

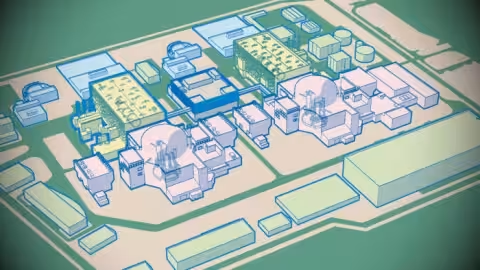

Commonwealth Fusion Systems plans to use the money to complete its Sparc fusion demonstration machine and begin work on developing a power plant in Virginia. The group secured a deal in June to supply 200 megawatts of electricity to technology giant Google.

The Google deal was one of only a handful of such commercial agreements in the sector and placed CFS at the forefront of fusion companies trying to perfect the technology and develop a commercially viable machine.

CFS has raised almost $3bn since it was spun out of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2018, drawing investors amid heightened interest in nuclear to meet surging energy demand from artificial intelligence.

“Investors recognise that CFS is making fusion power a reality. They see that we are executing and delivering on our objectives,” said Bob Mumgaard, chief executive and co-founder of CFS.

New investors in CFS’s latest funding round, which raised $863mn, include NVentures, Nvidia’s venture capital arm, Morgan Stanley’s Counterpoint Global and a consortium of 12 Japanese companies led by Mitsui & Co.

Nuclear fusion seeks to produce clean energy by combining atoms in a manner that releases a significant amount of energy. In contrast, fission — the process used in conventional nuclear power — splits heavy atoms such as uranium into smaller atoms, releasing heat.

CFS is also planning to build the world’s first large-scale fusion power plant in Virginia, which is home to the largest concentration of data centres in the world.

BloombergNEF estimates that US data centre power demand will more than double to 78GW by 2035, from about 35GW last year, and nuclear energy start-ups already have raised more than $3bn in 2025, a 400 per cent increase on 2024 levels.

But experts have warned that addressing the technological challenges to the development of fusion would be expensive, putting into question the viability of the technology.

No group has yet been able to produce more energy from a fusion reaction than the system itself consumes despite decades of experimentation.

“Fusion is radically difficult compared to fission,” said Mark Nelson, managing director of the consultancy Radiant Energy Group, pointing to the incredibly high temperatures and pressures required to combine atoms.

“The hard part is not making fusion reactors. Every step forward towards what may be a dead end economically, looks like something that justifies another billion or a Nobel Prize.”