AI Insights

NSF award boosts research into the future of battery-less devices

Xie’s research, titled “Holistic Cross-layer Solution Towards Instant, Adaptive, and Evolving Intelligence for Battery-less Systems,” will be funded for the next five years.

“By addressing challenges in energy efficiency, data processing latency and real-time decision-making, this project will enable robust, intelligent operation in highly resource-constrained environments, contributing to the next-generation of embedded AI systems,” said Xie.

Her expertise interfaces with microdevices, artificial intelligence and energy-efficient computing.

The project aims to transform how small smart devices operate in environments with limited access to electricity by utilizing self-powered computing systems that run entirely on energy harvested from the environment, such as solar, thermal and other ambient sources.

The research has broad applications across a range of industries including healthcare, agriculture, environmental monitoring, disaster response and other sectors where efficient and reliable devices can address the unique challenges of energy-constrained environments.

“In the next five to 10 years, battery-less energy harvesting technology has the potential to transform everyday life by enabling a new class of maintenance-free, intelligent and sustainable devices that operate without needing batteries or manual charging,” Xie said. “The ultimate goal is to create autonomous AI-enabled systems that can sense, learn and act continuously — without ever needing a battery.”

The project also is focused on enhancing computer science education at UTSA, and the supported students will gain hands-on experience in hardware software co-design, machine learning and system integration.

Xie plans to integrate the research into her courses to prepare the next generation of computer science professionals who will address the increased demand for this emerging technology.

AI Insights

How AI is eroding human memory and critical thinking

AI Insights

The human thinking behind artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence is built on the thinking of intelligent humans, including data labellers who are paid as little as US$1.32 per hour. Zena Assaad, an expert in human-machine relationships, examines the price we’re willing to pay for this technology. This article was originally published in the Cosmos Print Magazine in December 2024.

From Blade Runner to The Matrix, science fiction depicts artificial intelligence as a mirror of human intelligence. It’s portrayed as holding a capacity to evolve and advance with a mind of its own. The reality is very different.

The original conceptions of AI, which hailed from the earliest days of computer science, defined it as the replication of human intelligence in machines. This definition invites debate on the semantics of the notion of intelligence.

Can human intelligence be replicated?

The idea of intelligence is not contained within one neat definition. Some view intelligence as an ability to remember information, others see it as good decision making, and some see it in the nuances of emotions and our treatment of others.

As such, human intelligence is an open and subjective concept. Replicating this amorphous notion in a machine is very difficult.

Software is the foundation of AI, and software is binary in its construct; something made of two things or parts. In software, numbers and values are expressed as 1 or 0, true or false. This dichotomous design does not reflect the many shades of grey of human thinking and decision making.

Not everything is simply yes or no. Part of that nuance comes from intent and reasoning, which are distinctly human qualities.

To have intent is to pursue something with an end or purpose in mind. AI systems can be thought to have goals, in the form of functions within the software, but this is not the same as intent.

The main difference is goals are specific and measurable objectives whereas intentions are the underlying purpose and motivation behind those actions.

You might define the goals as ‘what’, and intent as ‘why’.

To have reasoning is to consider something with logic and sensibility, drawing conclusions from old and new information and experiences. It is based on understanding rather than pattern recognition. AI does not have the capacity for intent and reasoning and this challenges the feasibility of replicating human intelligence in a machine.

There is a cornucopia of principles and frameworks that attempts to address how we design and develop ethical machines. But if AI is not truly a replication of human intelligence, how can we hold these machines to human ethical standards?

Can machines be ethical?

Ethics is a study of morality: right and wrong, good and bad. Imparting ethics on a machine, which is distinctly not human, seems redundant. How can we expect a binary construct, which cannot reason, to behave ethically?

Similar to the semantic debate around intelligence, defining ethics is its own Pandora’s box. Ethics is amorphous, changing across time and place. What is ethical to one person may not be to another. What was ethical 5 years ago may not be considered appropriate today.

These changes are based on many things; culture, religion, economic climates, social demographics, and more. The idea of machines embodying these very human notions is improbable, and so it follows that machines cannot be held to ethical standards. However, what can and should be held to ethical standards are the people who make decisions for AI.

Contrary to popular belief, technology of any form does not develop of its own accord. The reality is their evolution has been puppeteered by humans. Human beings are the ones designing, developing, manufacturing, deploying and using these systems.

If an AI system produces an incorrect or inappropriate output, it is because of a flaw in the design, not because the machine is unethical.

The concept of ethics is fundamentally human. To apply this term to AI, or any other form of technology, anthropomorphises these systems. Attributing human characteristics and behaviours to a piece of technology creates misleading interpretations of what that technology is and is not capable of.

Decades long messaging about synthetic humans and killer robots have shaped how we conceptualise the advancement of technology, in particular, technology which claims to replicate human intelligence.

AI applications have scaled exponentially in recent years, with many AI tools being made freely available to the general public. But freely accessible AI tools come at a cost. In this case, the cost is ironically in the value of human intelligence.

The hidden labour behind AI

At a basic level, artificial intelligence works by finding patterns in data, which involves more human labour than you might think.

ChatGPT is one example of AI, referred to as a large language model (LLM). ChatGPT is trained on carefully labelled data which adds context, in the form of annotations and categories, to what is otherwise a lot of noise.

Using labelled data to train an AI model is referred to as supervised learning. Labelling an apple as “apple”, a spoon as “spoon”, a dog as “dog”, helps to contextualise these pieces of data into useful information.

When you enter a prompt into ChatGPT, it scours the data it has been trained on to find patterns matching those within your prompt. The more detailed the data labels, the more accurate the matches. Labels such as “pet” and “animal” alongside the label “dog” provide more detail, creating more opportunities for patterns to be exposed.

Data is made up of an amalgam of content (images, words, numbers, etc.) and it requires this context to become useful information that can be interpreted and used.

As the AI industry continues to grow, there is a greater demand for developing more accurate products. One of the main ways for achieving this is through more detailed and granular labels on training data.

Data labelling is a time consuming and labour intensive process. In absence of this work, data is not usable or understandable by an AI model that operates through supervised learning.

Despite the task being essential to the development of AI models and tools, the work of data labellers often goes entirely unnoticed and unrecognised.

Data labelling is done by human experts and these people are most commonly from the Global South – Kenya, India and the Philippines. This is because data labelling is labour intensive work and labour is cheaper in the Global South.

Data labellers are forced to work under stressful conditions, reviewing content depicting violence, self-harm, murder, rape, necrophilia, child abuse, bestiality and incest.

Data labellers are pressured to meet high demands within short timeframes. For this, they earn as little as US$1.32 per hour, according to TIME magazine’s 2023 reporting, based on an OpenAI contract with data labelling company Sama.

Countries such as Kenya, India and the Philippines incur less legal and regulatory oversight of worker rights and working conditions.

Similar to the fast fashion industry, cheap labour enables cheaply accessible products, or in the case of AI, it’s often a free product.

AI tools are commonly free or cheap to access and use because costs are being cut around the hidden labour that most people are unaware of.

When thinking about the ethics of AI, cracks in the supply chain of development rarely come to the surface of these discussions. People are more focused on the machine itself, rather than how it was created. How a product is developed, be it an item of clothing, a TV, furniture or an AI-enabled capability, has societal and ethical impacts that are far reaching.

A numbers game

In today’s digital world, organisational incentives have shifted beyond revenue and now include metrics around the number of users.

Releasing free tools for the public to use exponentially scales the number of users and opens pathways for alternate revenue streams.

That means we now have a greater level of access to technology tools at a fraction of the cost, or even at no monetary cost at all. This is a recent and rapid change in the way technology reaches consumers.

In 2011, 35% of Americans owned a mobile phone. By 2024 this statistic increased to a whopping 97%. In 1973, a new TV retailed for $379.95 USD, equivalent to $2,694.32 USD today. Today, a new TV can be purchased for much less than that.

Increased manufacturing has historically been accompanied by cost cutting in both labour and quality. We accept poorer quality products because our expectations around consumption have changed. Instead of buying things to last, we now buy things with the expectation of replacing them.

The fast fashion industry is an example of hidden labour and its ease of acceptance in consumers. Between 1970 and 2020, the average British household decreased their annual spending on clothing despite the average consumer buying 60% more pieces of clothing.

The allure of cheap or free products seems to dispel ethical concerns around labour conditions. Similarly, the allure of intelligent machines has created a facade around how these tools are actually developed.

Achieving ethical AI

Artificial intelligence technology cannot embody ethics; however, the manner in which AI is designed, developed and deployed can.

In 2021, UNESCO released a set of recommendations on the ethics of AI, which focus on the impacts of the implementation and use of AI. The recommendations do not address the hidden labour behind the development of AI.

Misinterpretations of AI, particularly those which encourage the idea of AI developing with a mind of its own, isolate the technology from the people designing, building and deploying that technology. These are the people making decisions around what labour conditions are and are not acceptable within their supply chain, what remuneration is and isn’t appropriate for the skills and expertise required for data labelling.

If we want to achieve ethical AI, we need to embed ethical decision making across the AI supply chain; from the data labellers who carefully and laboriously annotate and categorise an abundance of data through to the consumers who don’t want to pay for a service they have been accustomed to thinking should be free.

Everything comes at a cost, and ethics is about what costs we are and are not willing to pay.

AI Insights

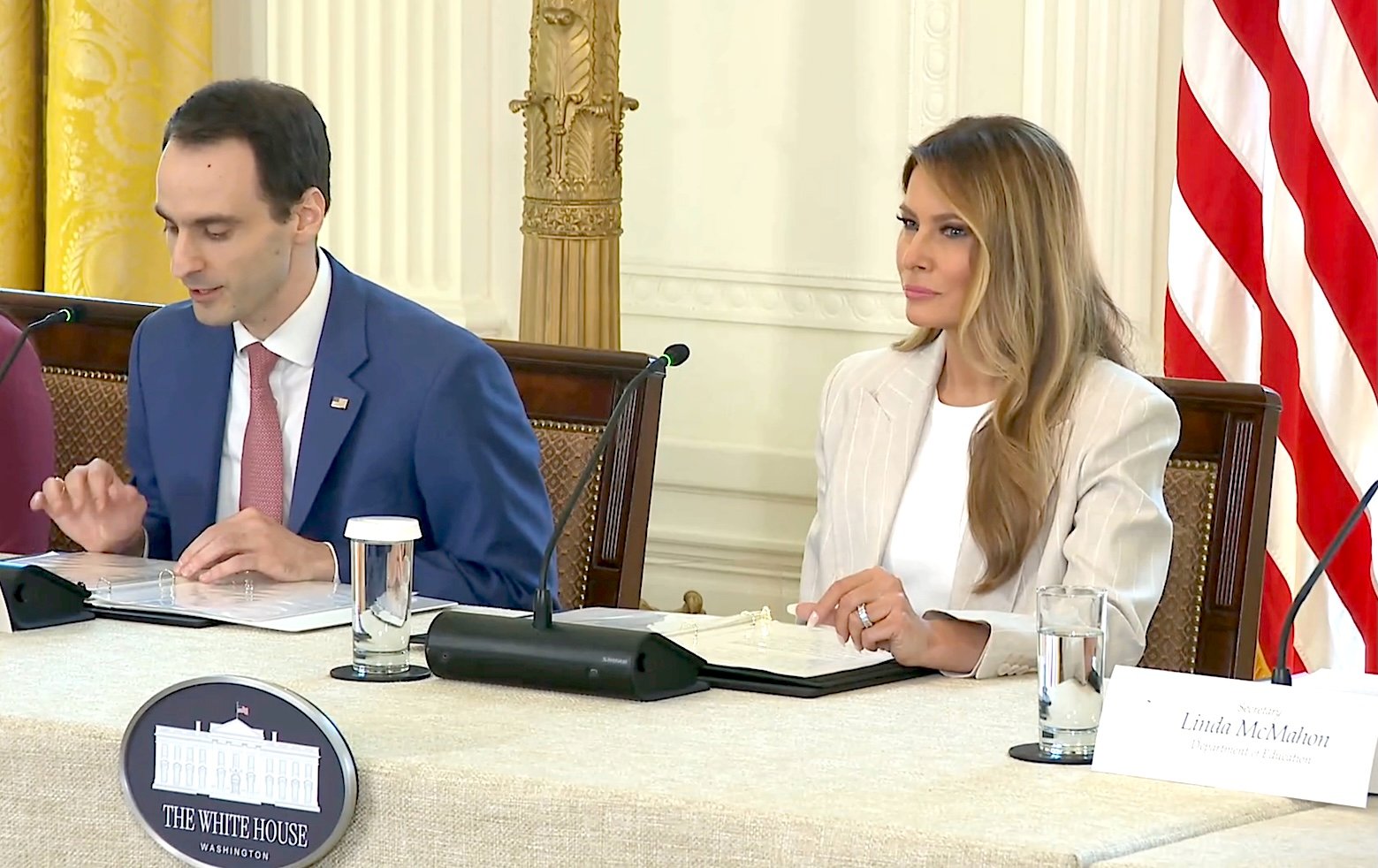

‘The robots are here’: Melania Trump encourages America to lead world in artificial intelligence at White House event

A “moment of wonder” is how First Lady Melania Trump described the era of artificial intelligence during rare public remarks Thursday at a White House event on AI education.

“It is our responsibility to prepare children in America,” Trump said as she hosted the White House Task Force on Artificial Intelligence Education in Washington, D.C. Citing self-driving cars, robots in the operating room, and drones redefining war, Trump said “every one of these advancements is powered by AI.”

The meeting, attended by The Lion and other reporters, also included remarks from task force members, including Cabinet Secretaries Christopher Wright (Energy), Linda McMahon (Education), Brooke Rollins (Agriculture), and Lori Chavez-DeRemer (Labor), as well as technology leaders in the private sector.

“The robots are here. Our future is no longer science fiction,” Trump added, noting that AI innovation is spurring economic growth and will “serve as the underpinning of every business sector in our nation,” including science, finance, education, and design.

Trump predicted AI will unfold as the “single largest growth category in our nation” during President Donald Trump’s administration, and she would not be surprised if AI “becomes known as the greatest engine of progress” in America’s history.

“But as leaders and parents, we must manage AI’s growth responsibly,” she warned. “During this primitive stage, it is our duty to treat AI as we would our own children – empowering, but with watchful guidance.”

Thursday’s event marked the AI task force’s second meeting since President Trump signed an executive order in April to advance AI education among American youth and students. The executive order set out a policy to “promote AI literacy and proficiency among Americans” by integrating it into education, providing training for teachers, and developing an “AI-ready workforce.”

The first lady sparked headlines for her embrace of AI after using it to narrate her audiobook, Melania. She also launched a national Presidential AI Challenge in August, encouraging students and teachers to “unleash their imagination and showcase the spirit of American innovation.” The challenge urges students to submit projects that involve the study or use of AI to address community challenges and encourages teachers to use “creative approaches” for using AI in K-12 education.

At the task force meeting, Trump called for Americans to “lead in shaping a new magnificent world” in the AI era, and said the Presidential AI Challenge is the “first major step to galvanize America’s parents, educators and students with this mission.”

During the event, McMahon quipped that Barron Trump, the Trumps’ college-aged son, was “helping you with a little bit of this as well,” receiving laughs from the audience. The education secretary also said her department is working to embrace AI through its grants, future investments and even its own workforce.

“In supporting our current grantees, we’ve issued a Dear Colleague letter telling anyone who has received an ED grant that AI tools and technologies are allowable use of federal education funds,” she said. “Our goal is to empower states and schools to begin exploring AI integration in a way that works best for their communities.”

Rollins spoke next, noting that rural Americans are too often “left behind” without the same technological innovations that are available in urban areas. “We cannot let that happen with AI,” the agriculture secretary said.

“I want to say that President Trump has been very clear, the United States will lead the world in artificial intelligence, period, full stop. Not China, not of our other foreign adversaries, but America,” Rollins said. “And with the First Lady’s leadership and the presidential AI challenge. We are making sure that our young people are ready to win that race.”

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms4 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi