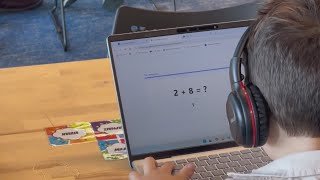

U.S. Secretary of Education Linda McMahon toured an Austin private school on Tuesday, which claims it helps students “Learn 2x in 2 Hours.”

Source: Youtube

With Japan’s Ministry of Education, also known as MEXT, planning to raise enrolment limits at certain universities to “encourage the recruitment of outstanding international students”, India has become a key market for some of the country’s top institutions.

Recently, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba agreed to boost Japanese private investment in India to about $6.8 billion annually over the next decade, up from $2.7bn a year in the 2010s.

In particular, Indian workers and students are seen as a way to help address Nippon’s labor shortages amid its aging population and declining birth rate.

I would love to see more students from South Asia joining us to experience world-class education, an exciting campus life, affordable tuition, and a safe, welcoming society

Kaori Hayashi, University of Tokyo India Office

In light of this, Navi Japan, a one-stop app for Indian students to access information on universities, language labs, accommodation, scholarships, and careers, has officially launched today (September 8), helping Japan attract top Indian student talent – especially in fields like AI.

“Backed by real-time support features such as live chat, video counselling, and local engagement opportunities at schools and university campuses across India, Navi Japan ensures that every student can make confident, informed decisions about studying in Japan and feel personally supported throughout their journey from aspiration to relocation,” stated Adrian Mutton, founder and CEO, Acumen.

Although there are only about 1,400 Indian international students currently in Japan, the strengthening of Japanese-Indian ties in areas such as economics, security, technology, and people-to-people exchange is expected to drive a sharp rise in that number in the coming years.

According to Acumen, the Navi Japan app, available for free on Android and iOS, has a goal of engaging over 100,000 students from India and South Asia within the next 24 months, while also helping its partner institutions like the University of Tokyo showcase their diverse range of programs.

“Japanese universities offer a diverse range of academic programs, including degree courses taught in English,” stated Dr. Kaori Hayashi, director of University of Tokyo India Office.

“I would love to see more students from South Asia joining us to experience world-class education, an exciting campus life, affordable tuition, and a safe, welcoming society. We look forward to working with Acumen to achieve our goal.”

U.S. Secretary of Education Linda McMahon toured an Austin private school on Tuesday, which claims it helps students “Learn 2x in 2 Hours.”

Source: Youtube

Artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping how students write essays, practise languages and complete assignments. Teachers are also experimenting with AI for lesson planning, grading and feedback. The pace is so fast that schools, universities and policymakers are struggling to keep up.

What often gets overlooked in this rush is a basic question: how are students and teachers actually learning to use AI?

À lire aussi :

AI in schools — here’s what we need to consider

Right now, most of this learning happens informally. Students trade advice on TikTok or Discord, or even ask ChatGPT for instructions. Teachers swap tips in staff rooms or glean information from LinkedIn discussions.

These networks spread knowledge quickly but unevenly, and they rarely encourage reflection on deeper issues such as bias, surveillance or equity. That is where formal teacher education could make a difference.

Research shows that educators are under-prepared for AI. A recent study found many lack skills to assess the reliability and ethics of AI tools. Professional development often stops at technical training and neglects wider implications. Meanwhile, uncritical use of AI risks amplifying bias and inequity.

In response, I designed a professional development module within a graduate-level course at Mount Saint Vincent University. Teacher candidates engaged in:

The goal was not simply to learn how to use AI, but to move from casual experimentation to critical engagement.

During the sessions, patterns quickly emerged. Teacher candidates were enthusiastic about AI to begin with, and remained so. Participants reported a stronger ability to evaluate tools, recognize bias and apply AI thoughtfully.

I also noticed that the language around AI shifted. Initially, teacher candidates were unsure about where to start, but by the end of the sessions, they were confidently using terms like “algorithmic bias” and “informed consent” with confidence.

Teacher candidates increasingly framed AI literacy as professional judgment, connected to pedagogy, cultural responsiveness and their own teacher identity. They saw literacy not only as understanding algorithms but also as making ethical classroom decisions.

The pilot suggests enthusiasm is not the missing ingredient. Structured education gave teacher candidates the tools and vocabulary to think critically about AI.

These classroom findings mirror broader institutional challenges. Universities worldwide have adopted fragmented policies: some ban AI, others cautiously endorse it and many remain vague. This inconsistency leads to confusion and mistrust.

Alongside my colleague Emily Ballantyne, we examined how AI policy frameworks can be adapted for Canadian higher education. Faculty recognized AI’s potential but voiced concerns about equity, academic integrity and workload.

We proposed a model that introduced a “relational and affective” dimension, emphasizing that AI affects trust and the dynamics of teaching relationships, not only efficiency. In practice, this means that AI not only changes how assignments are completed, but also reshapes the ways students and instructors relate to one another in class and beyond.

Put differently, integrating AI in classrooms reshapes how students and teachers relate, and how educators perceive their own professional roles.

When institutions avoid setting clear policies, individual instructors are left to act as ad hoc ethicists without institutional backing.

Clear policies alone are not enough. For AI to genuinely support teaching and learning, institutions must also invest in building the knowledge and habits that sustain critical use. Policy frameworks provide direction, but their value depends on how they shape daily practice in classrooms.

Teacher education must lead on AI literacy. If AI reshapes reading, writing and assessment, it cannot remain an optional workshop. Programs must integrate AI literacy into curricula and outcomes.

Policies must be clear and practical. Teacher candidates repeatedly asked: “What does the university expect?” Institutions should distinguish between misuse (ghostwriting) and valid uses (feedback support), as recent research recommends.

Learning communities matter. AI knowledge is not mastered once and forgotten; it evolves as tools and norms change. Faculty circles, curated repositories and interdisciplinary hubs can help teachers share strategies and debate ethical dilemmas.

Equity must be central. AI tools embed biases from their training data and often disadvantage multilingual learners. Institutions should conduct equity audits and align adoption with accessibility standards.

Public debates about AI in classrooms often swing between two extremes: excitement about innovation or fear of cheating. Neither captures the complexity of how students and teachers are actually learning AI.

Informal learning networks are powerful but incomplete. They spread quick tips, but rarely cultivate ethical reasoning. Formal teacher education can step in to guide, deepen and equalize these skills.

When teachers gain structured opportunities to explore AI, they shift from passive adopters to active shapers of technology. This shift matters because it ensures educators are not merely responding to technological change, but actively directing how AI is used to support equity, pedagogy and student learning.

That is the kind of agency education systems must nurture if AI is to serve, rather than undermine, learning.

When OpenAI released “study mode” in July 2025, the company touted ChatGPT’s educational benefits. “When ChatGPT is prompted to teach or tutor, it can significantly improve academic performance,” the company’s vice president of education told reporters at the product’s launch. But any dedicated teacher would be right to wonder: Is this just marketing, or does scholarly research really support such claims?

While generative AI tools are moving into classrooms at lightning speed, robust research on the question at hand hasn’t moved nearly as fast. Some early studies have shown benefits for certain groups such as computer programming students and English language learners. And there have been a number of other optimistic studies on AI in education, such as one published in the journal Nature in May 2025 suggesting that chatbots may aid learning and higher-order thinking. But scholars in the field have pointed to significant methodological weaknesses in many of these research papers.

Other studies have painted a grimmer picture, suggesting that AI may impair performance or cognitive abilities such as critical thinking skills. One paper showed that the more a student used ChatGPT while learning, the worse they did later on similar tasks when ChatGPT wasn’t available.

In other words, early research is only beginning to scratch the surface of how this technology will truly affect learning and cognition in the long run. Where else can we look for clues? As a cognitive psychologist who has studied how college students are using AI, I have found that my field offers valuable guidance for identifying when AI can be a brain booster and when it risks becoming a brain drain.

Cognitive psychologists have argued that our thoughts and decisions are the result of two processing modes, commonly denoted as System 1 and System 2.

The former is a system of pattern matching, intuition and habit. It is fast and automatic, requiring little conscious attention or cognitive effort. Many of our routine daily activities – getting dressed, making coffee and riding a bike to work or school – fall into this category. System 2, on the other hand, is generally slow and deliberate, requiring more conscious attention and sometimes painful cognitive effort, but often yields more robust outputs.

We need both of these systems, but gaining knowledge and mastering new skills depend heavily on System 2. Struggle, friction and mental effort are crucial to the cognitive work of learning, remembering and strengthening connections in the brain. Every time a confident cyclist gets on a bike, they rely on the hard-won pattern recognition in their System 1 that they previously built up through many hours of effortful System 2 work spent learning to ride. You don’t get mastery and you can’t chunk information efficiently for higher-level processing without first putting in the cognitive effort and strain.

I tell my students the brain is a lot like a muscle: It takes genuine hard work to see gains. Without challenging that muscle, it won’t grow bigger.

Now imagine a robot that accompanies you to the gym and lifts the weights for you, no strain needed on your part. Before long, your own muscles will have atrophied and you’ll become reliant on the robot at home even for simple tasks like moving a heavy box.

AI, used poorly – to complete a quiz or write an essay, say – lets students bypass the very thing they need to develop knowledge and skills. It takes away the mental workout.

Using technology to effectively offload cognitive workouts can have a detrimental effect on learning and memory and can cause people to misread their own understanding or abilities, leading to what psychologists call metacognitive errors. Research has shown that habitually offloading car navigation to GPS may impair spatial memory and that using an external source like Google to answer questions makes people overconfident in their own personal knowledge and memory.

Are there similar risks when students hand off cognitive tasks to AI? One study found that students researching a topic using ChatGPT instead of a traditional web search had lower cognitive load during the task – they didn’t have to think as hard – and produced worse reasoning about the topic they had researched. Surface-level use of AI may mean less cognitive burden in the moment, but this is akin to letting a robot do your gym workout for you. It ultimately leads to poorer thinking skills.

In another study, students using AI to revise their essays scored higher than those revising without AI, often by simply copying and pasting sentences from ChatGPT. But these students showed no more actual knowledge gain or knowledge transfer than their peers who worked without it. The AI group also engaged in fewer rigorous System 2 thinking processes. The authors warn that such “metacognitive laziness” may prompt short-term performance improvements but also lead to the stagnation of long-term skills.

Offloading can be useful once foundations are in place. But those foundations can’t be formed unless your brain does the initial work necessary to encode, connect and understand the issues you’re trying to master.

Returning to the gym metaphor, it may be useful for students to think of AI as a personal trainer who can keep them on task by tracking and scaffolding learning and pushing them to work harder. AI has great potential as a scalable learning tool, an individualized tutor with a vast knowledge base that never sleeps.

AI technology companies are seeking to design just that: the ultimate tutor. In addition to OpenAI’s entry into education, in April 2025 Anthropic released its learning mode for Claude. These models are supposed to engage in Socratic dialogue, to pose questions and provide hints, rather than just giving the answers.

Early research indicates AI tutors can be beneficial but introduce problems as well. For example, one study found high school students reviewing math with ChatGPT performed worse than students who didn’t use AI. Some students used the base version and others a customized tutor version that gave hints without revealing answers. When students took an exam later without AI access, those who’d used base ChatGPT did much worse than a group who’d studied without AI, yet they didn’t realize their performance was worse. Those who’d studied with the tutor bot did no better than students who’d reviewed without AI, but they mistakenly thought they had done better. So AI didn’t help, and it introduced metacognitive errors.

Even as tutor modes are refined and improved, students have to actively select that mode and, for now, also have to play along, deftly providing context and guiding the chatbot away from worthless, low-level questions or sycophancy.

The latter issues may be fixed with better design, system prompts and custom interfaces. But the temptation of using default-mode AI to avoid hard work will continue to be a more fundamental and classic problem of teaching, course design and motivating students to avoid shortcuts that undermine their cognitive workout.

As with other complex technologies such as smartphones, the internet or even writing itself, it will take more time for researchers to fully understand the true range of AI’s effects on cognition and learning. In the end, the picture will likely be a nuanced one that depends heavily on context and use case.

But what we know about learning tells us that deep knowledge and mastery of a skill will always require a genuine cognitive workout – with or without AI.

The Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

SDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

Journey to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

Mumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

Happy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

Macron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

VEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

Kayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

OpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi