Education

Multi-stakeholder perspective on responsible artificial intelligence and acceptability in education

Education stands as a cornerstone of society, nurturing the minds that will ultimately shape our future1. As we advance into the twenty-first century, exponentially developing technologies and the convergence of knowledge across disciplines are set to have a significant influence on various aspects of life2, with education a crucial element that is both disrupted by and critical to progress3. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI), notably generative AI and generative pre-trained transformers4 such as ChatGPT, with its new capabilities to generalise, summarise, and provide human-like dialogue across almost every discipline, is set to disrupt the education sector from K-12 through to lifelong learning by challenging traditional systems and pedagogical approaches5,6.

Artificial intelligence can be defined as the simulation of human intelligence and its processes by machines, especially computer systems, which encompasses learning (the acquisition of information and rules for using information), reasoning (using rules to reach approximate or definite conclusions), and flexible adaptation7,8,9. In education, AI, or AIED, aims to “make computationally precise and explicit forms of educational, psychological and social knowledge which are often left implicit“10. Therefore, the promise of AI to revolutionise education is predicated on its ability to provide adaptive and personalised learning experiences, thereby recognising and nurturing the unique cognitive capabilities of each student11. Furthermore, integrating AI into pedagogical approaches and practice presents unparalleled opportunities for efficiency, global reach, and the potential for the democratisation of education unattainable by traditional approaches.

AIED encompasses a broad spectrum of applications, from adaptive learning platforms that curate customised content to fit individual learning styles and paces12 to AI-driven analytics tools that forecast student performance and provide educators with actionable insights13. Moreover, recent developments in AIED have expanded the educational toolkit to include chatbots for student support, natural language processing for language learning, and machine learning for automating administrative tasks, allowing educators to focus more or exclusively on teaching and mentoring14. These tools have recently converged into multipurpose, generative pre-trained transformers (GPTs). These GPTs are large language models (LLMs) utilizing transformers to combine large language data sets and immense computing power to create an intelligent model that, after training, can generate complex, advanced, human-level output15 in the form of text, images, voice, and video. These models are capable of multi-round human-computer dialogues, continuously responding with novel output each time users input a new prompt due to having been trained with data from the available corpus of human knowledge, ranging from the physical and natural sciences through medicine to psychiatry.

This convergence highlights that a step change has occurred in the capabilities of AI to act not only as a facilitator of educational content but also as a dynamic tool with agentic properties capable of interacting with stakeholders at all levels of the educational ecosystem, enhancing and potentially disrupting the traditional pedagogical process. Recently, the majority of the conversation within the current literature concerning AIED is focused on the aspect of cheating or plagiarism16,17,18, with some calls to examine the ethics of AI19. This focus falls short of addressing the multidimensional, multi-stakeholder nature of AI-related issues in education. It fails to consider that AI is already here, accessible, and proliferating. It is this accessibility and proliferation that motivates the research presented in this manuscript. The release of generative AI globally and its application within education raises significant ethical concerns regarding data privacy, AI agency, transparency, explainability, and additional psychosocial factors, such as confidence and trust, as well as the acceptance and equitable deployment of the technology in the classroom20.

As education touches upon all members and aspects of society, we, therefore, seek to investigate and understand the level of acceptability of AI within education for all stakeholders: students, teachers, parents, school staff, and principals. Using factors derived from the explainable AI literature21 and the UNESCO framework for AI in education22. We present research that investigates the role of agency, privacy, explainability, and transparency in shaping the perceptions of global utility (GU), individual usefulness (IU), confidence, justice, and risk toward AI and the eventual acceptance of AI and intention to use (ITU) in the classroom. These factors were chosen as the focus for this study based on feedback from focus groups that identified our four independent variables as the most prominent factors influencing AI acceptability, aligning with prior IS studies21 that have demonstrated their central role in AI adoption decisions. Additionally, these four variables directly influence other AI-related variables, such as fairness -conceptualized in our study as confidence- suggesting a mediating role in shaping intentions to use AI.

In an educational setting, the deployment of AI has the potential to redistribute agency over decision-making between human actors (teachers and students) and algorithmic systems or autonomous agents. As AI systems come to assume roles traditionally reserved for educators, the negotiation of autonomy between educator, student, and this new third party becomes a complex balancing act in many situations, such as personalising learning pathways, curating content, and even evaluating student performance23,24.

Educational professionals face a paradigm shift where the agency afforded to AI systems must be weighed against preserving the educators’ pedagogical authority and expertise25. However, this is predicated on human educators providing additional needs such as guidance, motivation, facilitation, and emotional investment, which may not hold as AI technology develops26 That is not to say that AI will supplant the educator in the short term; rather, it highlights the need to calibrate AI’s role within the pedagogical process carefully.

Student agency, defined as the individual’s ability to act independently and make free choices27, can be compromised or enhanced by AI. While AI can personalise learning experiences, adaptively responding to student needs, thus promoting agency28, it can conversely reduce student agency through over-reliance, whereby AI-generated information may diminish students’ critical thinking and undermine the motivation toward self-regulated learning, leading to a dependency29.

Moreover, in educational settings, the degree of agency afforded to AI systems, i.e., its autonomy and decision-making capability, raises significant ethical considerations at all stakeholder levels. A high degree of AI agency risks producing “automation complacency“30, where stakeholders within the education ecosystem, from parents to teachers, uncritically accept AI guidance due to overestimating its capabilities. Whereas a low degree of agency essentially hamstrings the capabilities of AI and the reason for its application in education. Therefore, ensuring that AI systems are designed and implemented to support and enhance human agency through human-centred alignment and design rather than replacing it requires thorough attention to the design and deployment of these technologies31.

In conclusion, educational institutions must navigate the complex dynamics of assigned agency when integrating AI into pedagogical frameworks. This will require careful consideration of the balance between AI autonomy and human control to prevent the erosion of stakeholders’ agency at all levels of the education ecosystem and, thus, increase confidence and trust in AI as a tool for education.

Establishing confidence in AI systems is multifaceted, encompassing the ethical aspects of the system, the reliability of AI performance, the validity of its assessments, and the robustness of data-driven decision-making processes32,33. Thus, confidence in AI systems within educational contexts centres on their capacity to operate reliably and contribute meaningfully to educational outcomes.

Building confidence in AI systems is directly linked to the consistency of their performance across diverse pedagogical scenarios34. Consistency and reliability are judged by the AI system’s ability to function without frequent errors and sustain its performance over time35. Thus, inconsistencies in AI performance, such as system downtime or erratic behaviour, may alter perceptions of utility and significantly decrease user confidence.

AI systems are increasingly employed to grade assignments and provide feedback, which are activities historically under the supervision of educators. Confidence in these systems hinges on their ability to deliver feedback that is precise, accurate, and contextually appropriate36. The danger of misjudgment by AI, particularly in subjective assessment areas, can compromise its credibility37, increasing risk perceptions for stakeholders such as parents and teachers and directly affecting learners’ perceptions of how fair and just AI systems are.

AI systems and the foundation models they are built upon are trained over immense curated datasets to drive their capabilities38. The provenance of these data, the views of those who curate the subsequent training data, and how that data is then used within the model (that creates the AI) is of critical importance to ensure bias does not emerge when the model is applied19,39. To build trust in AI, stakeholders at all levels must have confidence in the integrity of the data used to create an AI, the correctness of analyses performed, and any decisions proposed or taken40. Moreover, the confidence-trust relationship in AI-driven decisions requires transparency about data sources, collection methods, and explainable analytical algorithms41.

Therefore, to increase and maintain stakeholder confidence and build trust in AIED, these systems must exhibit reliability, assessment accuracy, and transparent and explainable decision-making. Ensuring these attributes requires robust design, testing, and ongoing monitoring of AI systems, the models they are built upon, and the data used to train them.

Trust in AI is essential to its acceptance and utilisation at all stakeholder levels within education. Confidence and trust are inextricably linked42, representing a feedback loop wherein confidence builds towards trust and trust instils confidence, and the reverse holds that a lack of confidence fails to build trust. Thus, a loss of trust decreases confidence. Trust in AI is engendered by many factors, including but not limited to the transparency of AI processes, the alignment of AI functions with educational ethics, including risk and justice, the explainability of AI decision-making, privacy and the protection of student data, and evidence of AI’s effectiveness in improving learning outcomes33,43,44.

Standing as a proxy for AI, studies of trust toward automation45,46 have identified three main factors that influence trust: performance (how automation performs), process (how it accomplishes its objective), and purpose (why the automation was built originally). Accordingly, educators and students are more likely to trust AI if they can comprehend its decision-making processes and the rationale behind its recommendations or assessments47. Thus, if AI operates opaquely as a “black box”, it can be difficult to accept its recommendations, leading to concerns about its ethical alignment. Therefore, the dynamics of stakeholder trust in AI hinges on the assurance that the technology operates transparently and without bias, respects student diversity, and functions fairly and justly48.

Furthermore, privacy and security directly feed into the trust dynamic in that educational establishments are responsible for the data that AI stores and utilises to form its judgments. Tools for AIED are designed, in large part, to operate at scale, and a key component of scale is cloud computing, which involves resource sharing, which refers to the technology and the data stored on it49. This resource sharing makes the boundary between personal and common data porous, which is viewed as a resource that many technology companies can use to train new AI models or as a product50. Thus, while data breaches may erode trust in AIED in an immediate sense, far worse is the hidden assumption that all data is common. However, this issue can be addressed by stakeholders at various levels through ethical alignment negotiations, robust data privacy measures, security protocols, and policy support to enforce them22,51.

Accountability is another important element of the AI trust dynamic, and one inextricably linked to agency and the problem of control. It refers to the mechanisms in place to hold system developers, the institutions that deploy AI, and those that use AI responsible for the functioning and outcomes of AI systems33. The issue of who is responsible for AI’s decisions or mistakes is an open question heavily dependent on deep ethical analysis. However, it is of critical and immediate importance, particularly in education, where the stakes include the quality of teaching and learning, the fairness of assessments, and the well-being of students.

In conclusion, trust in AI is an umbrella construct that relies on many factors interwoven with ethical concerns. The interdependent relationship between confidence and trust suggests that the growth of one promotes the enhancement of the other. At the same time, their decline, through errors in performance, process, or purpose, leads to mutual erosion. The interplay between confidence and trust points towards explainability and transparency as potential moderating factors in the trust equation.

The contribution of explainability and transparency towards trust in AI systems is significant, particularly within the education sector; they enable stakeholders to understand and rationalise the mechanisms that drive AI decisions52. Comprehensibility is essential for educators and students not only to follow but also to assess and accept the judgments made by AI systems critically53,54. Transparency gives users visibility of AI processes, which opens AI actions to scrutiny and validation55.

Calibrating the right balance between explainability and transparency in AI systems is crucial in education, where the rationale behind decisions, such as student assessments and learning path recommendations, must be clear to ensure fairness and accountability32,56. The technology is perceived to be more trustworthy when AI systems articulate, in an accessible manner, their reasoning for decisions and the underlying data from which they are made57. Furthermore, transparency allows educators to align AI-driven interventions with pedagogical objectives, fostering an environment where AI acts as a supportive tool rather than an inscrutable authority58,59,60.

Moreover, the explainability and transparency of AI algorithms are not simply a technical requirement but also a legal and ethical one, depending on interpretation, particularly in light of regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which posits a “right to explanation” for decisions made by automated systems61,62,63. Thus, educational institutions are obligated to deploy AI systems that perform tasks effectively and provide transparent insights into their decision-making processes in a transparent manner64,65.

In sum, explainability and transparency are critical co-factors in the trust dynamic, where trust appears to be the most significant factor toward the acceptance and effective use of AI in education. Systems that employ these methods enable stakeholders to understand, interrogate, and trust AI technologies, ensuring their responsible and ethical use in educational contexts.

When taken together, this discussion points to the acceptance of AI in education as a multifaceted construct, hinging on a harmonious yet precarious balance of agency, confidence, and trust underpinned by the twin pillars of explainability and transparency. Agency involving the balance of autonomy between AI, educators, and students requires careful calibration between AI autonomy and educator control to preserve pedagogical integrity and student agency, which is vital for independent decision-making and critical thinking. Accountability, closely tied to agency, strengthens trust by ensuring that AI systems are answerable for their decisions and outcomes, reducing risk perceptions. Trust in AI and its co-factor confidence are fundamental prerequisites for AI acceptance in educational environments. The foundation of this trust is built upon factors such as AI’s performance, the clarity of its processes, its alignment with educational ethics, and the security and privacy of data. Explainability and transparency are critical in strengthening the trust dynamic. They provide stakeholders with insights into AI decision-making processes, enabling understanding and critical assessment of AI-generated outcomes and helping to improve perceptions of how just and fair these systems are.

However, is trust a one-size-fits-all solution to the acceptance of AI within education, or is it more nuanced, where different AI applications require different levels of each factor on a case-by-case basis and for different stakeholders? This research seeks to determine to what extent each factor contributes to the acceptance and intention to use AI in education across four use cases from a multi-stakeholder perspective.

Drawing from this broad interdisciplinary foundation that integrates educational theory, ethics, and human-computer interaction, this study investigates the acceptability of artificial intelligence in education through a multi-stakeholder lens, including students, teachers, and parents. This study employs an experimental vignette approach, incorporating insights from focus groups, expert opinion and literature review to develop four ecologically valid scenarios of AI use in education. Each scenario manipulates four independent variables—agency, transparency, explainability, and privacy—to assess their effects on perceived global utility, individual usefulness, justice, confidence, risk, and intention to use. The vignettes were verified through multiple manipulation checks, and the effects of independent variables were assessed using previously validated psychometric instruments administered via an online survey. Data were analysed using a simple mediation model to determine the direct and indirect effects between the variables under consideration and stakeholder intention to use AI.

Education

A window into America’s high schools slams shut

This story was reported by and originally published by APM Reports in connection with its podcast Sold a Story: How Teach Kids to Read Went So Wrong.

The choices you make as a teenager can shape the rest of your life. If you take high school classes for college credit, you’re more likely to enroll at a university. If you take at least 12 credits of classes during your first year there, you’re more likely to graduate. And those decisions may even influence whether you develop dementia during your later years.

These and insights from thousands of other studies can all be traced to a trove of data that the federal government started collecting more than 50 years ago. Now that effort is over.

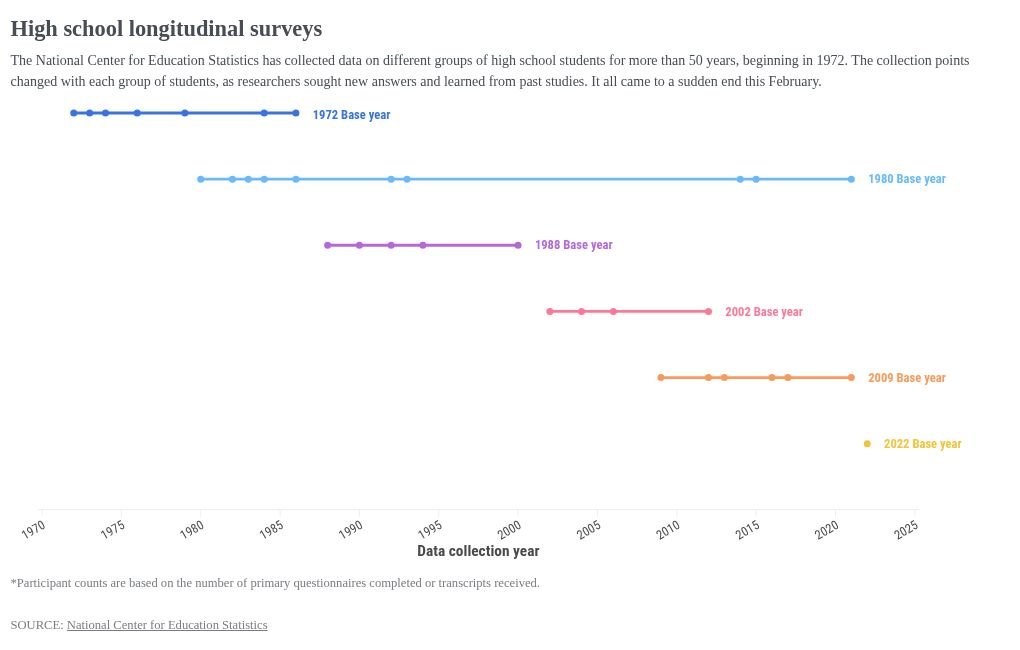

On a single day in February, the Trump administration and its Department of Government Efficiency canceled a long-running series of surveys called the high school longitudinal studies. The surveys started in 1972, and they had gathered data on more than 135,000 high school students through their first decade or so of adulthood — sometimes longer.

“For 50 years, we’ve been mapping a timeline of progress of our high school system, and we’re going to have a big blank,” said Adam Gamoran, who leads the William T. Grant Foundation and was nominated to head up the Education Department’s research and statistics arm under President Biden, but was never confirmed. “That’s very frustrating.”

The data collection effort has been going on since before the founding of the modern Department of Education. Thousands of journal articles, books, dissertations and reports have relied on this data to form conclusions about American education — everything from how high school counselors should be spending their days to when students should start taking higher-level math classes.

The Department of Government Efficiency first canceled contracts for the collection of new long-term high school data and then started laying off staff. The National Center for Education Statistics used to have nearly 100 employees. Today, only three remain.

“The reduction — annihilation — of NCES functionally is a very serious issue,” said Felice Levine, former executive director of the American Educational Research Association, one of the groups suing the administration over these actions. “Maybe it doesn’t appear to be as sexy as other topics, but it really is the backbone of knowledge building and policymaking.”

The Department of Education is reviewing how longitudinal studies “fit into the national data collection strategy based on studies’ return on investment for taxpayers,” according to an email from its spokesperson. The statement also said the department’s Institute of Education Sciences, which is in charge of overseeing research and gathering statistics, remains committed to “mission-critical functions.”

“It seems to me that even if you were the most hardcore libertarian who wants the government to regulate almost nothing, collecting national statistics is about the most innocuous and useful thing that a government could do,” said Stuart Buck, executive director of the Good Science Project, a group advocating less bureaucracy in science funding.

“The idea of a Department of Governmental Efficiency is an excellent idea, and I hope we try it out sometime,” he said. But the effort, “as it currently exists, I would argue, is often directly opposed to efficiency. Like, they’re doing the exact opposite.”

He likened the approach to “someone showing up to your house and claiming they saved you $200 a month, and it turns out they canceled your electricity.”

Related: Become a lifelong learner. Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter featuring the most important stories in education.

Since the effort began in the early 1970s, the federal government has collected data on six large groups of high school students, each numbering in the tens of thousands. Researchers surveyed each group at least once during high school, along with their parents and teachers. Researchers then contacted the students periodically after that, generally over the course of a decade or so — sometimes longer. They collected transcripts and other documents to track progress, too. In total, the data set contains thousands of variables.

The studies are called longitudinal, because they take place over a long time. The methodology is similar to studies that track twins over their lifetimes to determine which traits are genetic and which are caused by their experiences. Such data sets are valuable because they allow researchers to tease out effects that can’t be seen in a single snapshot, but they are rare because they require sustained funding over decades. And the high school data covers a large number of participants selected to represent the national population, giving insights that can be broadly applicable across states.

That vast repository of data affects students “indirectly, but profoundly,” said Andrew Byrne, who runs the math department at Greenwich High School in Connecticut. For example, research based on the data has shown that high school students who take classes for college credit have a better chance of finishing their bachelor’s degrees on time.

Byrne said that research informed the school’s decision to start offering a new Advanced Placement precalculus class when the College Board unveiled it two years ago. The new offering gave some high school students in lower-level math classes the opportunity to get college credit for the first time.

“Success in AP precalculus could empower them to believe they can succeed in college-level classes overall,” Byrne said. A student probably would not read the academic research, but “they live the results of the decisions that data informs,” he said.

Follow-up surveys for the group first contacted in 2009 — made up of people who started high school during the Great Recession — and for students who were high school freshmen in 2022 have been canceled. The latter group, who were middle schoolers during the pandemic, will be graduating next year.

Elise Christopher oversaw the high school longitudinal studies at the National Center for Education Statistics until she was laid off in March along with dozens of her colleagues. Christopher, a statistician who worked at the center for more than 14 years, is concerned about the data that was scheduled to be collected this year — and now won’t be.

“We can’t just pick this back up later,” she said. “They won’t be in high school. We won’t be able to understand what makes them want to come to school every day, because they’ll be gone.”

Researchers were hoping to learn more about why chronic absenteeism has persisted in schools even years after Covid-19 abated, Christopher explained. They were also hoping to understand whether students are now less interested in attending college than previous generations.

“Every single person in this country who’s been educated in the past 50 years has benefited from something that one of these longitudinal surveys has done,” she said.

Levine said the planned follow-up with students from the 2009 high school group would have helped reveal how a greater emphasis on math, science and technology in some states has influenced student decision-making. Were they more likely to study the hard sciences in college? Did they continue on to careers in those fields?

“These are the kinds of things that the public wants to know about, families want to know about, and school administrators and counselors want to know about,” she said.

Related: Suddenly sacked

About 25,000 people who completed the high school survey in 1980 were contacted again by researchers decades later.

Rob Warren, the director of the University of Minnesota’s Institute for Social Research and Data Innovation, is hoping those people — now in their 60s — may help him and other researchers gain new insights into why some people develop dementia, while others with similar brain chemistry don’t.

“Education apparently plays a big role in who’s resilient,” Warren said. “That’s kind of a mystery.”

The people who participated in the high school study may offer a unique set of clues about why education matters, Warren explained.

“You need all that detail about education, and you need to be able to see them decades later, when they’re old enough to start having memory decline,” he said. Other studies can measure cognition, but to measure whether education plays a role in dementia outcomes, “you can’t really test (that) with other data,” he said.

So Warren’s team got permission from the federal government to contact the group in 2019. Researchers asked all the usual types of questions about their jobs and lives, but also gave them cognitive tests, asked medical questions, and even collected samples of their blood to monitor how their brains were changing as they aged.

Warren is continuing his research even though the federal government has canceled future high school surveys. But the staffing cuts at the Department of Education have hampered his ability to hand the data off to the center or share it with other researchers. To do that, he needs permission from the Department of Education, but getting it has been a challenge

“Very often you don’t hear anything back, ever, and sometimes you do, but it takes a very long time,” Warren said. Even drafting legal agreements to make the data available to the National Institutes of Health — another federal agency, which funded his data collection effort and would be responsible for handling the medical data — has been a bottleneck.

Such agreements would involve a bunch of lawyers, Warren said, and the Department of Education has laid off most of its legal team.

If the data isn’t made available to other researchers, Warren said, questions about dementia may go unanswered and “NIH’s large investment in this project will be wasted.”

Kate Martin contributed to this report.

Education

Empowering Minds: The Rise of Artificial Intelligence in Education Curricula

VMPL

New Delhi [India], September 10: The education landscape is one of the most transformed domains of Artificial Intelligence (AI), as institutions across the globe realise its significant potential. From personalised learning experiences to AI-powered assessments, AI is redefining how knowledge is created, delivered, and absorbed. Hence, educational institutions have adopted robust frameworks to integrate AI into their curriculum, ensuring that students not only understand the nuances of the technology but also learn to apply it ethically and effectively.

“At Les Roches, AI is not treated as a stand-alone subject but as a natural extension of our experiential model of education. Our strategy is to integrate it into the learning journey wherever it makes sense, so that students encounter AI in authentic, industry-relevant contexts. In practice, this means combining classroom theory with hands-on exposure to real technologies: revenue management simulators, marketing platforms, robotics, and AI-driven personalization systems, among others,” says Ms. Susana Garrido (MBA), Director of Innovation and EdTech & Clinical Professor in Marketing at Les Roches.

Echoing similar sentiments, Dr. Sandeep Singh Solanki, Dean of Post Graduate Studies at BIT Mesra, highlights a multifaceted approach to seamlessly integrate AI into the academic ecosystem.

”We have adopted a multifaceted approach to integrate AI into our curriculum, including teaching students about contemporary AI tools and how they can be an enabler for academic and career growth. Moreover, we are also emphasising consistent teacher training to effectively blend AI into our pedagogy for enhanced learning outcomes. In addition, we are fostering strategic industry partnerships to offer students hands-on exposure to real-world AI applications and emerging technologies,” says Dr. Solanki.

With a firm view that AI must be a part of the student learning journey, Mr. Kunal Vasudeva, Co-founder & Managing Director of the Indian School of Hospitality, has made it a compulsory subject for all students.

“We are very clear that AI has to be part of the student journey, and we have made it a compulsory subject from this year onwards. It is not something optional or an ‘elective.’ At the same time, we’re learning as we go. Our facilitators are being upskilled in using AI as a tool, and we’re in active conversations with partners such as Marriott, Accor, Nestle Professional, and JLL to see how best to bring real applications into the classroom,” says Mr. Vasudeva.

Educational institutions are also actively equipping students with the key knowledge and skills to not only understand but also harness the transformative power of artificial intelligence in ways that are both effective and responsible.

“We emphasize responsible AI use as much as technical competence. Students are trained to balance efficiency with ethics by embedding modules on AI ethics, data privacy, and bias management within courses. Conducting workshops on digital hygiene and cybersecurity helps sensitize students about risks in AI adoption. Encouraging debates and roleplays on real-world ethical dilemmas in AI ensures that graduates not only know how to use AI but also how to use it responsibly in decision-making,” says Prof (Dr.) Daviender Narang – Director, Jaipuria Institute of Management, Ghaziabad.

Airing similar viewpoints, Dr. Shiva Kakkar, AI-Transformation, Jaipuria Institute of Management (Seth MR Jaipuria Group), states, “Our philosophy is simple: AI should increase cognitive effort, not reduce it. When students use AI for self-reflection on their CVs or practice interviews, the system doesn’t hand over answers but asks harder questions. This nudges them to articulate their experiences better, spot weaknesses, and think deeply. On ethics, we train students to treat AI like a colleague whose work must always be verified. They learn to recognize bias, challenge hallucinations, and decide when to rely on human judgment.”

Meanwhile, institutions are navigating a complex terrain that includes upskilling faculty, updating legacy systems, and ensuring equitable access to AI tools for all students. While enthusiasm for AI integration is high, the path forward demands sustained investment, collaborative innovation, and a deep commitment to ethical education.

“Integrating AI into pedagogy inevitably comes with challenges, and at Les Roches one of the most significant has been the varying levels of comfort among our faculty. We have professors who are seasoned hoteliers with decades of operational expertise, and others who are digital natives more at ease with emerging technologies. To address this, we developed a progressive, sequential approach where new tools are introduced step by step. Faculty receive training, try out tools in safe environments at their own pace, and gradually bring them into the classroom,” says Ms. Garrido.

Similarly, Dr. Solanki underlines that consistent upskilling of educators and data privacy remain key challenges amid the AI revolution.

“One of the primary challenges that we faced was to ensure that our faculty was sufficiently trained to utilise and educate students about AI tools. This demands rapid, continuous upskilling, and we are significantly investing in it. Another major challenge revolved around data privacy and ethical usage, especially when students were using AI platforms for academic support. To prevent the misuse of these tools, support and guidelines are provided,” said Mr. Solanki.

Furthermore, industry partnerships are playing a crucial role in accelerating AI integration within academic environments. By collaborating with leading corporations and tech innovators, educational institutions are bridging the gap between theoretical learning and real-world application.

“Industry partnership is the most critical aspect for us. We will do whatever it takes to understand, apply, and work with the industry so that the ultimate beneficiary is the student. Our role is to stay in constant motion with the industry, bring that knowledge back, and reinforce it in the classroom. Anything that advances knowledge and critical thinking for our students is a priority. Partnerships with groups like Marriott, Accor, Nestle Professional, and JLL allow us to see how AI is being applied on the ground,” says Mr. Vasudeva.

Similarly, Dr. Kakkar states that industry collaborations for AI are a win-win situation for both academic institutions and industry players.

“We look for partnerships that deepen learning. We are in discussions with both global and Indian AI initiatives to bring cutting-edge exposure to our students. At the same time, the tools we are developing for our classrooms are also being adapted for corporate learning and leadership development. In effect, the classroom becomes our laboratory, and industry gets a tested, field-ready solution,” says Dr. Kakkar.

Inclusivity remains the foundation of AI integration in esteemed educational institutions. Acknowledging that access to technology and digital literacy varies across student demographics, institutions are designing AI-enabled learning environments that are accessible, equitable, and supportive of diverse learning requirements.

“Inclusivity is our core value. We ensure AI as a simplifier. By using AI-driven learning platforms, students from non-technical backgrounds can overcome learning gaps through personalized support with the tools powered by AI. Our institution provides guided workshops and resources so that all students, irrespective of prior exposure, can benefit equally. We also showcase AI not just as a tool for IT or analytics, but for marketing creativity, financial risk management, HR analytics, and beyond–ensuring inclusivity across disciplines,” says Prof (Dr.) Narang.

In a similar vein, Dr. Solanki states, “We ensure that our AI-enabled learning environments are accessible to all students, irrespective of their socio-economic backgrounds and levels of digital literacy. We also offer foundational AI knowledge to every student through open elective courses and MOOC courses to enable them to effectively use AI tools. The institute follows NEP guidelines, and we advocate for every department to adequately introduce AI in their course curriculum. These endeavours reflect our commitment to equity in education.”

It is also important to mention that teacher empowerment is central to unlocking the full potential of AI in academic settings. As facilitators of learning, educators must be equipped not only with technical know-how but also with the confidence and creativity to integrate AI meaningfully into their teaching practices.

“Our faculty are at the heart of the Les Roches experience and empowering them to use AI confidently is one of our top priorities. We provide structured training programs that focus not just on technical skills but also on practical applications–how AI can help design more engaging classes, create better assessments, or streamline teaching preparation. Tools are rolled out gradually, so professors can build confidence without pressure,” says Ms. Garrido.

In agreement with her stance, Dr. Kakkar states, “We see teachers not as ‘users of AI tools’ but as designers of AI-enabled learning experiences. Our workshops focus on helping faculty rethink pedagogy: How can AI generate counterarguments in a strategy class? How can it provide alternative data sets in a finance discussion? How can it surface hidden biases in an organizational behaviour exercise? Teachers are also given insights into student progress through analytics, so instead of spending time on repetitive feedback, they can focus on mentoring and higher-order guidance.”

As AI continues to reshape the educational landscape, prominent institutions are demonstrating that its successful integration lies in a holistic approach. These institutions are not only preparing students for the future but are also redefining what meaningful, responsible, and innovative education looks like in the age of AI.

(ADVERTORIAL DISCLAIMER: The above press release has been provided by VMPL. ANI will not be responsible in any way for the content of the same)

(This content is sourced from a syndicated feed and is published as received. The Tribune assumes no responsibility or liability for its accuracy, completeness, or content.)

Education

La Crosse Public Library hosts AI education event | News

We recognize you are attempting to access this website from a country belonging to the European Economic Area (EEA) including the EU which

enforces the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and therefore access cannot be granted at this time.

For any issues, contact news8@wkbt.com or call 608-784-7897.

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms4 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi