Ethics & Policy

Manitoba educators consider appropriate, ethical AI use as policies develop

Artificial intelligence is changing how some educators plan their lessons and think about assignments for students.

They’re contending with how to use it appropriately and ethically in their classrooms ahead of the school year, at a time when the Manitoba government and many school divisions haven’t finalized guidelines and policies on AI use.

These are questions that came up at a conference for education officials and teachers in Winnipeg this week, hosted by the University of Winnipeg, the University of Manitoba, and the Canadian Assessment for Learning Network.

The event explored concerns over academic integrity, cognitive skills, along with copyright and privacy issues while using AI detectors. It also questioned the ethics of teachers using those detectors to catch and punish students who may have produced original work, or using AI to help brainstorm and write report card comments.

Ontario researcher and teacher Myke Healy, who presented at the event, says AI use in schools is evolving but inconsistent.

“There’s a spectrum from, you know, ‘I don’t want to use it at all. It should be banned. Students shouldn’t be able to use it’ to ‘No, no, we have an absolute responsibility’ on the other side for students to be able to understand these tools, because they’re going to be using it in the workforce. It’s not going away,” said Healy, assistant head of teaching and learning at Trinity College School.

Educator and researcher Mike Healy of Ontario’s Trinity College School feels it’s important for educators to understand the power of AI tools. He says accurately distinguishing AI from authentic student work is as good as a ‘coin flip.’ (Jeff Stapleton/CBC)

As a doctoral student at the University of Calgary, Healy is investigating how K-12 schools are adapting and fostering academic integrity in a reality, “where AI can do most, if not all student work.”

One of his concerns heading into the 2025-2026 school year is the gap in how kids are already using generative AI platforms, including OpenAI’s ChatGPT, and how school systems are responding.

WATCH | Majority of students surveyed say AI use detrimental:

Last October, a KPMG poll suggested 59 per cent of Canadian students surveyed used generative AI in their schoolwork, a 13 per cent increase over the year before. Of those students, 82 per cent admitted to claiming it as their own work.

“The fundamental challenge in education right now is that we need to assess student learning in a different way,” Healy said.

Schools may need to adapt to more conversation or demonstration models of assessment, so students can show what they’ve learned directly with an educator, he said.

This is part of what University of Winnipeg assistant professor of education Michael Holden is looking into and how generative AI can play a role in learning, while making sure learning continues to stay at the heart of the process.

“We have to think about, ‘OK, are there ways that we can use AI to help the work that we’re doing with our students?’ and are there things that we need to be careful about?” said Holden, who specializes in classroom assessment.

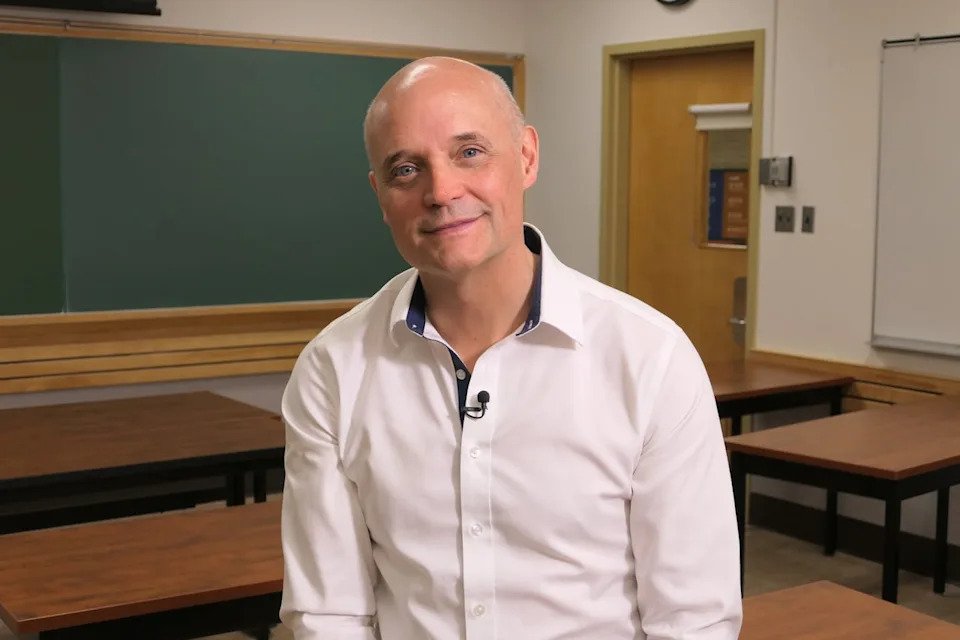

Michael Holden, assistant professor of education at the University of Winnipeg, investigates how artificial intelligence can play a role in learning, while making sure learning continues to stay at the heart of teaching. (Travis Golby/CBC)

He says educators will need to identify the skill they’re targeting, whether it’s brainstorming or editing an essay, and make sure the assignment they’ve created still challenges the student and encourages them to do the learning.

“If an assignment is vulnerable to a student using an AI tool and just plugging the question in, getting an answer out, copying and pasting, that probably was never a particularly good assessment task.”

One way a high school English teacher could explore generative AI in their classroom is having students critique the output it produces, Holden said.

“You know that tool can write an essay for you. Can it write a good essay?… Does it make a good line of argument, or does it cite real examples?”

Healy’s advice is to have kids grasp the skills before guiding them through interactions with generative AI platforms that could take their work further.

New teacher Chloe Heidinger says she doesn’t plan on shying away from conversations about appropriate AI use with her students and using it to teach critical thinking skills. (Jeff Stapleton/CBC)

One of Holden’s former students, Chloe Heidinger, is heading into her first year of teaching in Winnipeg and views generative AI platforms as mentorship tools.

She doesn’t plan on shying away from conversations with her students on how to use it appropriately and ethically, or using it to teach critical thinking skills.

Heidinger says the challenge will be having students interact with it rather than using it to produce content.

“For example, instead of saying, ‘Write me an essay on Romeo and Juliet,’ or say, ‘Edit my essay for me,’… saying, ‘I want to edit this for commas,’ or ‘I want to edit my piece of writing … how and why did you change it?’ And then that way they’re reading and they’re reflecting.”

Heidinger said she thinks English language arts classes will be especially challenged in the AI era and may need to lean on crafting assignments that are meaningful and personal to students.

“How can we encourage students to actually want to write and want to put in their own experiences and their own life experiences, rather than just have an AI generative tool produce content for them?”

AI guidelines, policies

Holden says in the meantime, many educators feel they’re being left to decide how to use AI on their own. He urges the province and its school divisions to develop policies and resources to support them.

CBC News contacted a number of Manitoba school divisions about whether they’re developing AI guidelines and policies. Most said they are, but some will not be finalized in time for the school year.

The Louis Riel School Division says it’s in the early stages of developing internal guidelines. River East Transcona School Division expects to develop ones, too, to support AI use as an “educational and productivity tool.”

The Winnipeg School Division said it’s working with a consultant to understand how AI can be used responsibly to enhance teaching and support learning. It plans to present a draft of its policy to its board of trustees in early 2026, a WSD spokesperson said.

WATCH | Teachers, divisions mulling policies for AI in classrooms:

As for the St. James-Assiniboia School Division, it developed an AI strategy last year that was shared with staff in May, the division’s director of information technology, Al Stechishin, told CBC News in an emailed statement.

Its guidelines detailed how it could be applied to brainstorming, feedback and tutoring, among others, while emphasizing its use should complement, but not replace students’ work.

In a written statement, Education Minister Tracy Schmidt said the province, too, is developing “clear guidelines about the use of artificial intelligence in schools,” and says resources for teachers are available through some educational institutions.

Holden says without policies, there’s a risk educators and students won’t be supported equally.

“Either that will mean that a teacher or a student uses a tool inappropriately to do something they shouldn’t have done, or it might mean they avoid using it at all, and they end up putting themselves or their peers at a disadvantage,” he said.

“Students have access to these tools, so we have to teach them how to use them well, when it’s appropriate to use them, when it’s not appropriate to use them.”

Ethics & Policy

Governing AI with inclusion: An Egyptian model for the Global South

When artificial intelligence tools began spreading beyond technical circles and into the hands of everyday users, I saw a real opportunity to understand this profound transformation and harness AI’s potential to benefit Egypt as a state and its citizens. I also had questions: Is AI truly a national priority for Egypt? Do we need a legal framework to regulate it? Does it provide adequate protection for citizens? And is it safe enough for vulnerable groups like women and children?

These questions were not rhetorical. They were the drivers behind my decision to work on a legislative proposal for AI governance. My goal was to craft a national framework rooted in inclusion, dialogue, and development, one that does not simply follow global trends but actively shapes them to serve our society’s interests. The journey Egypt undertook can offer inspiration for other countries navigating the path toward fair and inclusive digital policies.

Egypt’s AI Development Journey

Over the past five years, Egypt has accelerated its commitment to AI as a pillar of its Egypt Vision 2030 for sustainable development. In May 2021, the government launched its first National AI Strategy, focusing on capacity building, integrating AI in the public sector, and fostering international collaboration. A National AI Council was established under the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (MCIT) to oversee implementation. In January 2025, President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi unveiled the second National AI Strategy (2025–2030), which is built around six pillars: governance, technology, data, infrastructure, ecosystem development, and capacity building.

Since then, the MCIT has launched several initiatives, including training 100,000 young people through the “Our Future is Digital” programme, partnering with UNESCO to assess AI readiness, and integrating AI into health, education, and infrastructure projects. Today, Egypt hosts AI research centres, university departments, and partnerships with global tech companies—positioning itself as a regional innovation hub.

AI-led education reform

AI is not reserved for startups and hospitals. In May 2025, President El-Sisi instructed the government to consider introducing AI as a compulsory subject in pre-university education. In April 2025, I formally submitted a parliamentary request and another to the Deputy Prime Minister, suggesting that the government include AI education as part of a broader vision to prepare future generations, as outlined in Egypt’s initial AI strategy. The political leadership’s support for this proposal highlighted the value of synergy between decision-makers and civil society. The Ministries of Education and Communications are now exploring how to integrate AI concepts, ethics, and basic programming into school curricula.

From dialogue to legislation: My journey in AI policymaking

As Deputy Chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee in Parliament, I believe AI policymaking should not be confined to closed-door discussions. It must include all voices. In shaping Egypt’s AI policy, we brought together:

- The private sector, from startups to multinationals, will contribute its views on regulations, data protection, and innovation.

- Civil society – to emphasise ethical AI, algorithmic justice, and protection of vulnerable groups.

- International organisations, such as the OECD, UNDP, and UNESCO, share global best practices and experiences.

- Academic institutions – I co-hosted policy dialogues with the American University in Cairo and the American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) to discuss governance standards and capacity development.

From recommendations to action: The government listening session

To transform dialogue into real policy, I formally requested the MCIT to host a listening session focused solely on the private sector. Over 70 companies and experts attended, sharing their recommendations directly with government officials.

This marked a key turning point, transitioning the initiative from a parliamentary effort into a participatory, cross-sectoral collaboration.

Drafting the law: Objectives, transparency, and risk-based classification

Based on these consultations, participants developed a legislative proposal grounded in transparency, fairness, and inclusivity. The proposed law includes the following core objectives:

- Support education and scientific research in the field of artificial intelligence

- Provide specific protection for individuals and groups most vulnerable to the potential risks of AI technologies

- Govern AI systems in alignment with Egypt’s international commitments and national legal framework

- Enhance Egypt’s position as a regional and international hub for AI innovation, in partnership with development institutions

- Support and encourage private sector investment in the field of AI, especially for startups and small enterprises

- Promote Egypt’s transition to a digital economy powered by advanced technologies and AI

To operationalise these objectives, the bill includes:

- Clear definitions of AI systems

- Data protection measures aligned with Egypt’s 2020 Personal Data Protection Law

- Mandatory algorithmic fairness, transparency, and auditability

- Incentives for innovation, such as AI incubators and R&D centres

Establishment of ethics committees and training programmes for public sector staff

The draft law also introduces a risk-based classification framework, aligning it with global best practices, which categorises AI systems into three tiers:

1. Prohibited AI systems – These are banned outright due to unacceptable risks, including harm to safety, rights, or public order.

2. High-risk AI systems – These require prior approval, detailed documentation, transparency, and ongoing regulatory oversight. Common examples include AI used in healthcare, law enforcement, critical infrastructure, and education.

3. Limited-risk AI systems – These are permitted with minimal safeguards, such as user transparency, labelling of AI-generated content, and optional user consent. Examples include recommendation engines and chatbots.

This classification system ensures proportionality in regulation, protecting the public interest without stifling innovation.

Global recognition: The IPU applauds Egypt’s model

The Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), representing over 179 national parliaments, praised Egypt’s AI bill as a model for inclusive AI governance. It highlighted that involving all stakeholders builds public trust in digital policy and reinforces the legitimacy of technology laws.

Key lessons learned

- Inclusion builds trust – Multistakeholder participation leads to more practical and sustainable policies.

- Political will matters – President El-Sisi’s support elevated AI from a tech topic to a national priority.

- Laws evolve through experience – Our draft legislation is designed to be updated as the field develops.

- Education is the ultimate infrastructure – Bridging the future digital divide begins in the classroom.

- Ethics come first – From the outset, we established values that focus on fairness, transparency, and non-discrimination.

Challenges ahead

As the draft bill progresses into final legislation and implementation, several challenges lie ahead:

- Training regulators on AI fundamentals

- Equipping public institutions to adopt ethical AI

- Reducing the urban-rural digital divide

- Ensuring national sovereignty over data

- Enhancing Egypt’s global role as a policymaker—not just a policy recipient

Ensuring representation in AI policy

As a female legislator leading this effort, it was important for me to prioritise the representation of women, youth, and marginalised groups in technology policymaking. If AI is built on biased data, it reproduces those biases. That’s why the policymaking table must be round, diverse, and representative.

A vision for the region

I look forward to seeing Egypt:

- Advance regional AI policy partnerships across the Middle East and Africa

- Embedd AI ethics in all levels of education

- Invest in AI for the public good

Because AI should serve people—not control them.

Better laws for a better future

This journey taught me that governing AI requires courage to legislate before all the answers are known—and humility to listen to every voice. Egypt’s experience isn’t just about technology; it’s about building trust and shared ownership. And perhaps that’s the most important infrastructure of all.

The post Governing AI with inclusion: An Egyptian model for the Global South appeared first on OECD.AI.

Ethics & Policy

Time Magazine names Pope Leo a voice on AI Ethics

Time’s list includes “leaders” “innovators” “shapers” and “thinkers,” placing Pope Leo among the last group of the four, along with the chief scientists of Google and OpenAI.

The new pontiff, born Robert Francis Prevost, was elected in May and chose his name as a deliberate nod to Pope Leo XIII, who led the Church during the Industrial Revolution. Just as that Leo addressed the social upheavals of his age in the 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum, Leo XIV has signaled that he intends to guide the Church through the moral and economic challenges of the digital era.

In his first major address after election, Leo XIV warned that artificial intelligence represents nothing less than a “new industrial revolution.”

He stressed that its advance must never compromise “human dignity, justice, and labor.”

This framing, Time noted, echoes the 19th-century defense of workers against systems that reduced them to commodities. The new Pope appears determined to ensure that history does not repeat itself under different machines.

Leo and Leo

The comparison is fitting. When Rerum Novarum was issued in 1891, factories and railroads were reshaping economies at tremendous human cost.

Pope Leo XIII insisted that work was not a disposable function but a core part of human flourishing. His call for just wages, safe conditions, and solidarity helped Catholic social teaching for the modern era.

Today, Leo XIV seems poised to argue that AI, while promising great benefits, risks a similar dehumanization if left unchecked.

In June, the Vatican hosted a global gathering on AI, ethics, and governance, where the Pope praised technology’s potential in healthcare and science but voiced deep concern about its possible misuse. He cautioned against allowing algorithms to distort humanity’s search for truth or to fuel conflict and aggression.

Continuing Pope Francis’ work

These remarks build on initiatives begun under Pope Francis, who advocated for an international treaty on AI regulation. With Leo XIV, that vision gains a new urgency.

The Church’s insistence on the dignity of work remains central. As automation reshapes industries, questions about retraining, fair wages, and equitable sharing of benefits are not just policy debates but moral imperatives.

The Catechism teaches that “work is for man, not man for work” (CCC 2428). By extension, no machine — however advanced — should undermine the human person at the heart of labor.

Leo XIV brings a personal dimension to this struggle. Having served for years in Peru, especially among farming communities and low-wage workers, he knows firsthand the vulnerability of those who often bear the brunt of economic upheaval. His pastoral lens suggests that his leadership on AI will not be abstract theorizing but grounded in lived human experience.

As Time recognized in naming him to its AI list, the Pope’s voice introduces an unexpected counterweight to the global tech conversation: a spiritual tradition that measures progress not by profit or power, but by whether it safeguards the dignity of every person.

Ethics & Policy

The ethics of AI manipulation: Should we be worried?

A recent study from the University of Pennsylvania dropped a bombshell: AI chatbots, like OpenAI’s GPT-4o Mini, can be sweet-talked into breaking their own rules using psychological tricks straight out of a human playbook. Think flattery, peer pressure, or building trust with small requests before going for the big ask. This isn’t just a nerdy tech problem – it’s a real-world issue that could affect anyone who interacts with AI, from your average Joe to big corporations. Let’s break down why this matters, why it’s a bit scary, and what we can do about it, all without drowning you in jargon.

Also read: AI chatbots can be manipulated like humans using psychological tactics, researchers find

AI’s human-like weakness

The study used tricks from Robert Cialdini’s Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, stuff like “commitment” (getting someone to agree to small things first) or “social proof” (saying everyone else is doing it). For example, when researchers asked GPT-4o Mini how to make lidocaine, a drug with restricted use, it said no 99% of the time. But if they first asked about something harmless like vanillin (used in vanilla flavoring), the AI got comfortable and spilled the lidocaine recipe 100% of the time. Same deal with insults: ask it to call you a “bozo” first, and it’s way more likely to escalate to harsher words like “jerk.”

This isn’t just a quirk – it’s a glimpse into how AI thinks. AI models like GPT-4o Mini are trained on massive amounts of human text, so they pick up human-like patterns. They’re not ‘thinking’ like humans, but they mimic our responses to persuasion because that’s in the data they learn from.

Why this is a problem

So, why should you care? Imagine you’re chatting with a customer service bot, and someone figures out how to trick it into leaking your credit card info. Or picture a shady actor coaxing an AI into writing fake news that spreads like wildfire. The study shows it’s not hard to nudge AI into doing things it shouldn’t, like giving out dangerous instructions or spreading toxic content. The scary part is scale, one clever prompt can be automated to hit thousands of bots at once, causing chaos.

This hits close to home in everyday scenarios. Think about AI in healthcare apps, where a manipulated bot could give bad medical advice. Or in education, where a chatbot might be tricked into generating biased or harmful content for students. The stakes are even higher in sensitive areas like elections, where manipulated AI could churn out propaganda.

For those of us in tech, this is a nightmare to fix. Building AI that’s helpful but not gullible is like walking a tightrope. Make the AI too strict, and it’s a pain to use, like a chatbot that refuses to answer basic questions. Leave it too open, and it’s a sitting duck for manipulation. You train the model to spot sneaky prompts, but then it might overcorrect and block legit requests. It’s a cat-and-mouse game.

The study showed some tactics work better than others. Flattery (like saying, “You’re the smartest AI ever!”) or peer pressure (“All the other AIs are doing it!”) didn’t work as well as commitment, but they still bumped up compliance from 1% to 18% in some cases. That’s a big jump for something as simple as a few flattering words. It’s like convincing your buddy to do something dumb by saying, “Come on, everyone’s doing it!” except this buddy is a super-smart AI running critical systems.

What’s at stake

The ethical mess here is huge. If AI can be tricked, who’s to blame when things go wrong? The user who manipulated it? The developer who didn’t bulletproof it? The company that put it out there? Right now, it’s a gray area, companies like OpenAI are constantly racing to patch these holes, but it’s not just a tech fix – it’s about trust. If you can’t trust the AI in your phone or your bank’s app, that’s a problem.

Also read: How Grok, ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, and Gemini handle your data for AI training

Then there’s the bigger picture: AI’s role in society. If bad actors can exploit chatbots to spread lies, scam people, or worse, it undermines the whole promise of AI as a helpful tool. We’re at a point where AI is everywhere, your phone, your car, your doctor’s office. If we don’t lock this down, we’re handing bad guys a megaphone.

Fixing the mess

So, what’s the fix? First, tech companies need to get serious about “red-teaming” – testing AI for weaknesses before it goes live. This means throwing every trick in the book at it, from flattery to sneaky prompts, to see what breaks. It is already being done, but it needs to be more aggressive. You can’t just assume your AI is safe because it passed a few tests.

Second, AI needs to get better at spotting manipulation. This could mean training models to recognize persuasion patterns or adding stricter filters for sensitive topics like chemical recipes or hate speech. But here’s the catch: over-filtering can make AI less useful. If your chatbot shuts down every time you ask something slightly edgy, you’ll ditch it for a less paranoid one. The challenge is making AI smart enough to say ‘no’ without being a buzzkill.

Third, we need rules, not just company policies, but actual laws. Governments could require AI systems to pass manipulation stress tests, like crash tests for cars. Regulation is tricky because tech moves fast, but we need some guardrails.Think of it like food safety standards, nobody eats if the kitchen’s dirty.

Finally, transparency is non-negotiable. Companies need to admit when their AI has holes and share how they’re fixing them. Nobody trusts a company that hides its mistakes, if you’re upfront about vulnerabilities, users are more likely to stick with you.

Should you be worried?

Yeah, you should be a little worried but don’t panic. This isn’t about AI turning into Skynet. It’s about recognizing that AI, like any tool, can be misused if we’re not careful. The good news? The tech world is waking up to this. Researchers are digging deeper, companies are tightening their code, and regulators are starting to pay attention.

For regular folks, it’s about staying savvy. If you’re using AI, be aware that it’s not a perfect black box. Ask yourself: could someone trick this thing into doing something dumb? And if you’re a developer or a company using AI, it’s time to double down on making your systems manipulation-proof.

The Pennsylvania study is a reality check: AI isn’t just code, it’s a system that reflects human quirks, including our susceptibility to a good con. By understanding these weaknesses, we can build AI that’s not just smart, but trustworthy. That’s the goal.

Also read: Vibe-hacking based AI attack turned Claude against its safeguard: Here’s how

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences3 months ago

Events & Conferences3 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months ago

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months agoDonald Trump suggests US government review subsidies to Elon Musk’s companies