Education

Lessons from New Orleans’ ‘college for all’ push after Katrina : NPR

Geraldlynn Stewart poses for a portrait outside her home in New Orleans East.

Emily Kask/for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Emily Kask/for NPR

All through middle and high school in New Orleans, Geraldlynn Stewart heard the message every day: College was the key to a successful future. It was there on the banners that coated the doors and hallways, advertising far-flung schools, like Princeton University and Grinnell College. And she could hear it in the chants students recited over and over again. This is the way! We start the day! We get the knowledge to go to college!

Yet even after enrolling in 2014 at Dillard University, a private historically black college in the heart of New Orleans, Stewart never felt at ease in that prescribed path.

Like most of her classmates, Stewart came from a working class family. She didn’t have close relatives who had graduated from college. Even with her tuition covered by a state scholarship, and a small loan, it was an ongoing challenge to pay for books, gas, a lab coat for biology class, food and many other expenses. The then-18-year-old didn’t want to be a financial burden on her mother, who had multiple jobs in the French Quarter.

”My mom was a nonstop worker,” Stewart says, “she does that still to this day.”

So on top of her classes, Stewart had a nearly full time job at Waffle House.

But by her second semester at Dillard, the job had eclipsed school, and Stewart decided that she had to choose one or the other. She chose the job — a decision with financial and career implications that would ripple throughout the next decade.

“I gave up on myself,” she says now.

Having some college experience but no degree is a common narrative among New Orleanians around Stewart’s age. After Hurricane Katrina devastated the city 20 years ago, schoolchildren returned to a flurry of new charter schools opening up, many of them united in a mission that was starting to crest across the country: college for all.

It was a founding ambition of the Knowledge is Power Program (KIPP) national charter school network, which Stewart attended in New Orleans starting in 2006, when she was 10 years old.

“That was our most singular focus for those beginning years,” says Rhonda Kalifey-Aluise, the longtime CEO of KIPP New Orleans Schools.

The broader idea at the time was this: Schools that kept a relentless eye on sending more students to and through college could help lift the next generation of New Orleanians out of poverty.

But 20 years on, the legacy of that college push in the lives of Stewart and her peers is complicated.

Stewart, her sister and her stepsister all bought into the messaging, and gave college a try.

Each sister would, like Stewart, face immense obstacles in college from day one.

Geraldlynn Stewart at her high school graduation in 2014.

Courtesy of Sarah Carr

hide caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of Sarah Carr

“It was not a straight path at all,” says Stewart’s stepsister, Mary Dillon, who also attended a KIPP school. “ My journey through college was super hard…It was a lot of trials and tribulations, ups and downs.”

Their stories offer a microcosm of the challenges so many New Orleans students experience after high school – and they show the importance of understanding a community, and its needs and aspirations, when pushing students toward higher education.

More students are going to college. But many don’t stay

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans schools received an infusion of disaster recovery funds, and charter schools replaced traditional public schools in a way that had never been seen before. Those changes made a big difference in a system that serves mostly Black, lower-income students.

Before the storm, test scores in New Orleans were among the lowest in Louisiana, and in 2005 only 56% of students graduated from high school on time. The year before Katrina, just over a third of high school graduates enrolled in college. In the decade after Katrina, test scores, graduation rates and college enrollment rates all went up.

But those improvements haven’t extended in the same way to college graduation rates.

While a 2018 study found more students stayed in college compared to before the flood, a follow up in 2020 – that included students from Stewart’s era, who had spent much more time in post-Katrina schools – reported no significant change:

Before Katrina, about 1 in 6 New Orleans students didn’t make it past their first semester of college. More than a decade later, in 2016, that figure had barely changed.

“You do end up with a lot of students going to college and not finishing,” says Doug Harris, director of the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans at Tulane University, and a co-author of both reports.

In a school system that serves so many lower-income students, even the most academically prepared may quickly find themselves overwhelmed by personal and financial strains that their more affluent peers rarely encounter at college. Harris points out that lower-income students, in both Louisiana and nationally, have lower college completion rates on average.

“Twenty years post-Katrina, that is something that I’m still struck by, that education can’t solve for poverty in and of itself, ” says Vincent Rossmeier, who studies the city’s education system at Tulane’s Cowen Institute.

College dreams, and some naivete

Stewart’s introduction to KIPP came one summer evening in 2006, when a teacher at the brand new KIPP Believe College Prep stopped by her family’s home in the 7th Ward. The teacher hoped to recruit fifth graders, and Stewart’s mother liked what she heard. There would be strict rules, long school days, and a relentless focus on learning.

At that time, the city’s public school system was in the midst of a dramatic reconstitution: The predominantly Black teacher corps had lost their jobs, and new charter schools were opening up, often hiring young, white teachers and leaders from out of town. Those teachers, many of them recruited through Teach for America, were often devoted ambassadors for the college enrollment push, which had traction well beyond New Orleans.

In his first address to Congress in 2009, President Barack Obama asked every American to pursue some form of education beyond high school. “Whatever the training may be, every American will need to get more than a high school diploma,” he said.

For her part, Stewart felt ambivalent about higher education. Styling hair was a longtime passion, and she sometimes wondered if there was a way to pursue cosmetology.

But, she says, “ KIPP really made it a point—that’s what we want: college, college, college.”

A student takes the stairs at KIPP Believe College Prep, the middle school Geraldlynn Stewart and Mary Dillon attended in New Orleans, on May 6, 2008.

Nikki Kahn/The Washington Post via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Nikki Kahn/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Overall, she mostly enjoyed KIPP. And when middle school ended, her mother enrolled her at a KIPP high school — the first in New Orleans to open. (If KIPP ever started a college, Stewart joked that her mother would be first in line to sign her up.)

As a freshman in 2010, there were thermometer-shaped posters lining the hallways showing which families had started saving money for college. And the school’s principal regularly recited the mantra, “One thousand first generation college graduates by 2022.”

Stevona Elem-Rogers is a leader at Black Education for New Orleans, which supports Black educators and schools in the city. She says, in schools like Stewart’s, there was some naivete – especially among the mostly young, white teachers and leaders – about the particular challenges Black, first-generation students encounter at college. Vital questions and concerns could go unaddressed.

“You’re going to hype me up and tell me, ‘Go to college.’ What’s my money plan?” Elem-Rogers says. “What’s my full, thought-out plan for how I enter into this space? What am I majoring in? Have you helped me think through the nuances of that?”

Their college journeys weren’t easy

In 2014, Stewart arrived at her first English class at Dillard University wearing her Waffle House uniform – she didn’t have time to change. From the start, she juggled a full class load with a 30- to 35-hour work week.

“It started overpowering my going to school,” she says.

She started Dillard with a large group of classmates from KIPP. One of those classmates, Khalil Pollard, says they all struggled with financial concerns and family obligations.

“We were all dealing with family and personal issues, financial issues, and just trying to make it,” he says. “Being in school [we] were very broke, hungry, and didn’t have that many resources.”

Pollard took several Advanced Placement courses at his KIPP high school, so he was able to skip some classes at Dillard — a big boon, he says. But the intense regimentation and handholding at KIPP didn’t always help in terms of preparing students for the independence of college, Pollard adds. At Dillard, skills such as self-advocacy and time management were so important, and he often felt at a loss. “Once we got to college, you realize, damn, we weren’t prepared for this.”

Pollard had to take his younger sister to classes with him most days freshman year, and it consistently made him late. That was a major factor in his failing a class, he says, and losing crucial scholarship funds. If his mother hadn’t been able to take out a loan to help, Pollard says he would have dropped out.

One by one, he watched as his former KIPP classmates, including Stewart, did just that. He recalls that when he finally walked across the stage in 2018—right on time, against all odds—there was only one other student from his KIPP high school still with him.

“I had to fight and push through,” he says.

Stewart’s two sisters have similar stories of struggle.

Jasmine Stewart, Geraldlynn’s older sister, was the first in her family to enroll in college, at Southern University at New Orleans (SUNO), a public HBCU. She did not attend a KIPP school like her sister, but her high school also encouraged college, and she says her parents were influenced by the messaging that was pervasive in the city at the time.

Jasmine met her future husband at SUNO, but after three semesters of struggling with grades, and too little academic counseling and support, she decided to leave.

“At some point I felt like I was there because everybody else wanted me there,” she says.

Mary Dillon, their stepsister, was the youngest; she attended the same KIPP middle school that Geraldlynn did, and also enrolled at Dillard. Nothing was easy about her time there.

She had a baby in high school, who often had to accompany her to college classes. She says things were already tough when her uncle was shot and killed, making it impossible for her to focus on school.

“I flunked every class that semester and literally was about to quit,” she recalls.

Dillon credits mentors and teachers from her KIPP middle school for supporting her. “My journey through college was super hard and honestly, KIPP was right there every step of the way,” she says, adding that one advisor even flew in from out of state in a particularly rough moment to offer counsel.

With the help of some summer classes, Dillon graduated on time in 2019—a feat she had doubted would be possible many times over the years.

“It was a lot of hurdles: jumping, tripping, falling,” she says. “But I made it. I definitely made it.”

Where the sisters are now

The sisters are now in their late 20s and early 30s, and KIPP remains an integral part their lives: Five of their children now attend KIPP Believe, which has a middle school that two of the sisters attended. And Jasmine Stewart and Mary Dillon both work at KIPP Believe, as a paraprofessional and a teacher, respectively.

Jasmine says she loves her work, but she wants to lead her own classroom someday—something she can’t do without a college degree. So, at age 31, she’s back at SUNO, this time taking classes online. With a full-time job and two kids, she tries to cram all of her schoolwork into the weekend.

“I’ve been staying afloat,” she says, but “I can’t give it my all…I have to give it the best I can.” Jasmine adds that, “ It will be so worth it in the end.”

Dillon has taught third grade English at KIPP Believe’s elementary school for the past few years. She continues to push her family to get the education and training they need to pursue their dreams.

“We are going to get hurdles,” she says. “We just have to figure out what truly makes us happy and run with it, regardless of what tries to get in the way.”

For Geraldlynn Stewart, there continue to be some obstacles. Now 29, she lives with her partner and three kids in New Orleans East. She’s helped support her family through jobs at the airport, Walmart and now Target. But she has bigger career ambitions.

Geraldlynn Stewart (center) poses for a portrait outside her apartment complex with partner Will Porche, and her three children: Harlem, 6; Harvee’, 2; and Harmony, 8.

Emily Kask/for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Emily Kask/for NPR

“Financially, I’m not where I want to be, and it bothers me because I know I could have been in a different situation,” she says.

Earlier this year, Stewart had the opportunity to pursue a long-time dream: enrolling in a cosmetology program. She passed the admissions test and took the required tour. But there was one obstacle in her way: A $1,200 balance on a loan from her time at Dillard lingers. (She says, at one point, she had paid back the entire loan, but it was refunded during the pandemic and she spent the money, not realizing that it could come due again.) She can’t get financial support to attend this cosmetology program until that balance is cleared.

“My having that open loan is hindering me from even starting my career path,” she says.

“Now my struggle is being [29] with three kids,” she adds, “and not knowing what’s my purpose.”

“All students should have the opportunity to go to college, if they want to”

Today, surveys show many Americans are questioning the value of a college degree.

And despite years of many New Orleans high schools pushing for students to pursue higher education, a 2024 poll from the Cowen Institute found only 32% of New Orleans parents and guardians said their child planned to attend a four-year college. That number shrank even more for Black parents, to 23%, and for families that earn less than $40,000, it shrank to 13%. Lower-income parents were also the most likely to support increased career and trades training in the high schools.

KIPP leaders say they’re trying to change to better reflect their community. As at some other charters, there’s more of a priority on hiring teachers who come from similar backgrounds to the students.

Brother and sister Harlem and Harmony play on a playground outside their apartment complex in New Orleans. Both children attend a KIPP school, like their mom did.

Emily Kask/for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Emily Kask/for NPR

And there’s more of an emphasis on local traditions. In the spring, a classroom at KIPP Believe had a banner on the door advertising the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club — a historic, mostly Black Mardi Gras organization — not a college.

College persistence remains a struggle for KIPP’s New Orleans graduates, with the pandemic aggravating longstanding challenges for everyone, according to Kalifey-Aluise, KIPP New Orleans Schools’ CEO. But the charter network wasn’t able to provide college completion numbers for its graduates in New Orleans.

Over the years, KIPP has also mellowed when it comes to college for all. Kalifey-Aluise says the group remains committed to the idea that college is the surest path out of poverty. “We absolutely believe that all students should have the opportunity to go to college, if they want to.”

But college no longer looms so large. In recent years, KIPP’s high schools have prioritized individual college and career counseling; and they have also offered some access to technical fields, like Geraldlynn Stewart’s long-time passion, cosmetology.

“I think sometimes the perception is KIPP started as ‘college only’ and now we’re career and we’ve sort of abandoned one for the other,” says Kalifey-Aluise, adding that it’s really about both.

“If we do it well, students will be able to make whatever choice, right?” she says. “It’s whatever they want, not which one we want.”

For those who are college bound, the organization also tries to do a better job matching students to institutions where they will be more likely to thrive, says Korbin Johnson, a longtime principal for KIPP New Orleans.

“It’s not just, ‘Hey, what’s the top college you think you can get into? You gotta go there,'” he says.

Now, Johnson says, there’s often a deeper conversation. “Where do we think you’ll be most successful? And tell me what’s important to you? What do you want to study? How far away from home do you want to be?”

Geraldlynn Stewart feels as if she might have benefited from some of the changes at KIPP, especially the broader view of potential career paths.

“I wish they drilled what they’re doing now to those kids into us because I feel like we probably would have been better off,” she says.

Stewart’s oldest child, 8-year-old Harmony, says she has many career aspirations, including being a teacher or a doctor.

“My mom wants me to be an artist because I know how to draw very well,” Harmony says.

But in the end, Stewart cares most of all that her deeply creative daughter has the opportunity to experience “every little thing she possibly can.”

Whether college or not, she wants Harmony’s decisions and destiny to be entirely in her own hands.

Sarah Carr is the author of Hope Against Hope, which follows a principal, a teacher and a student — Geraldlynn Stewart — as they navigate New Orleans schools after Hurricane Katrina.

Reporting contributed by: Aubri Juhasz

Edited by: Nicole Cohen

Audio story produced by: Lauren Migaki

Education

Being shut out of required courses is delaying college students’ graduation

Ryan Arnoldy started community college with the goal of eventually transferring to a four-year university and getting a degree in chemical engineering.

Soon Arnoldy started running up against the same exasperating bottleneck faced by a majority of university and college students: Classes required for his major were often not taught during the semesters he needed them, or filled so quickly there were no seats left.

Colleges and universities manage to provide these required courses when their students need to take them only about 15 percent of the time, new research shows — a major reason fewer than half of students graduate on time, raising the amount it costs and time it takes to get degrees.

Now, with widespread layoffs and budget cuts on campuses, and as consumers are already increasingly questioning the value of a college education, the problem is expected to get worse.

“What is more foundational to what we do as colleges and universities than offering courses to students so they can graduate? And yet we’re only doing it right 15 percent of the time,” said Tom Shaver, founder and CEO of Ad Astra, a company that provides scheduling software to 550 universities and whose research is the basis for that statistic.

Three years into his time at Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kansas, Arnoldy has completed so few required credits that he changed his major to computer science, almost lost his financial aid, considered dropping out and wasted time in classes he found irrelevant but were the only ones available.

And he still has at least a year to go.

Though he’s determined to finish, and has narrowly held onto enough scholarships and grants to stay in school, being shut out of courses he needed to graduate means “I am going to literally spend four years in a community college to get a two-year degree,” said Arnoldy, who is 21.

At one point, when he went to his counselor’s office for help with this, he remembered, “I was bawling. It seems like things should be simpler. A lot of my peers are frustrated, too.”

This kind of experience is, in fact, widespread. Fifty-seven percent of students at all levels of higher education end up having to spend more time and money on college because their campuses don’t offer required courses when they need them, according to a study last year by Ad Astra.

Though its scheduling work means the company has a vested interest in highlighting this problem, independent scholars and university administrators generally confirm the finding.

“We’re forcing students to literally decelerate their progress to degrees, by telling them to do something they can’t actually do,” Shaver said.

Related: Interested in innovations in higher education? Subscribe to our free biweekly higher education newsletter.

Scheduling university and college courses is complex. Yet rather than use advanced technology to do it, some institutions still rely on “old-school” methods that include producing hard-copy spreadsheets, according to administrators trying to address the issue.

Mounting layoffs and budget problems in the wake of enrollment declines and federal spending cuts threaten to make this problem worse.

Colleges and universities have collectively laid off thousands of faculty and staff in the last six months, with more downsizing expected. Others are further trimming their number of courses.

The cash-strapped California State University system has eliminated 1,430 course sections this year, across seven of its 23 campuses, or 7 percent of the total at those campuses, a spokeswoman, Amy Bentley-Smith, confirmed. These include sections of required courses. At Cal State Los Angeles, for example, the number of sections of a required Introduction to American Government course has been reduced from 14 to nine.

“I would expect that course shutouts will start to get worse,” said Kevin Mumford, director of the Purdue University Research Center in Economics, who has also studied this.

In addition to taking longer and spending more to graduate, students who are shut out of required courses often change their majors, as Arnoldy did, or drop out, Mumford’s and other research has concluded.

Together with economists at Brigham Young University, Mumford found that when first-year students at Purdue couldn’t get into a required course, they were 35 percentage points less likely to ever take it and 25 percentage points less likely to enroll in any other course in the same subject.

The students were part of a freshman class in 2018 that was 7 percent larger than expected, and more than half could not get into at least one of their top six requested courses.

Many changed their majors — especially away from science, technology, engineering or math, often abbreviated STEM. Every required STEM course a student couldn’t get into lowered the probability that he or she would major in one of those fields, according to the study, which was released in May.

Women, already underrepresented in STEM, were particularly likely to quit, the study found.

“There’s already a lot of pressure on women in STEM fields, and this appears to be just one obstacle too many,” Mumford said.

Related: The Hechinger Report’s Tuition Tracker helps reveal the real cost of college

For every course they couldn’t get into, in any subject, women — though not men — were also more than 7 percent less likely to graduate within four years, with a financial toll averaging $800 for additional tuition and housing plus $1,500 in forgone wages.

Students at U.S. colleges and universities already spend more time and money getting their degrees than they expect to. Though 90 percent of freshmen say they plan to finish a four-year degree within four years or less, according to a national survey by an institute at UCLA last administered in 2019, federal data show that fewer than half of them do. More than a third still haven’t graduated after six years.

At community colleges nationwide, students who can’t get into courses they need are up to 28 percent more likely to take no classes at all that term, contributing to those delays in graduation, a 2021 study by scholars at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and the nonprofit Mathematica concluded. Two years later, they found, the students were up to 34 percent more likely to have transferred to a different school, a decision that typically costs even more time and money.

Shaver, of Ad Astra, called course scheduling “one of the most mathematically complex optimization problems out there.”

It requires balancing student demand with the availability of classrooms, labs and full- and part-time faculty, who are typically limited to teaching a maximum number of courses per term, take sabbaticals and sometimes prefer that their classes meet on Mondays through Thursdays in the middle of those days.

Related: To fill seats, more colleges offer credit for life experience

An increase in the number of students with double majors, minors and concentrations further complicates the process. So do the challenges confronted by part-time and older students, who typically don’t live on campus and have to juggle families and jobs. Such students are expected to comprise a growing proportion of enrollment as the number of 18- to 24-year-olds declines.

“There are so many obstacles students face, from transportation to work schedules to child care. Some can only take classes in the afternoon or on the weekends,” said Matt Jamison, associate vice president of academic success at Front Range Community College in Colorado.

Meanwhile, “we have instructors that have [outside] jobs and aren’t always available. And faculty can teach only so many courses.”

But Jamison found that students were being shut out of required classes at his college for other reasons that seemed harder to explain.

Front Range offers in-person courses on three campuses and others that can be streamed online in real time, for instance. But class periods on the separate campuses and online had different starting and ending times.

“Students couldn’t get courses they needed because they were scheduled over each other,” Jamison said.

Now the college has synchronized the schedules on all of its campuses and for courses taught live online. It’s adding course sections to better keep up with demand.

None of this is simple, Jamison said. The response from some faculty and staff on his campus about changing long-standing routines, he said, is “ ‘This is the way we’ve always done it.’ But it’s not necessarily the best way to do it.”

Front Range is one of several colleges and universities trying to improve the chances that its students can get into the courses they need to graduate. Others are using more online courses to help students meet requirements.

In California’s rural Central Valley, for example, community college students struggled to get into the advanced math courses they need toward degrees in STEM; only a third of the 15 community colleges in the area consistently offer the courses. So the University of California, Merced, launched a pilot program during the summer to provide these required classes online.

At Johnson County Community College, where Ryan Arnoldy goes, executive vice president and provost Michael McCloud acknowledged that students sometimes can’t get into classes they need. A big part of the problem, he said, is that they don’t meet with advisers who can help them plan their routes to degrees — a behavior he said he has seen increasingly among younger generations of students.

To address this, the college has begun requiring students to meet with advisers who can help them better plan which courses to take, and when. A small-scale pilot program showed that this, along with added tutoring and other student supports, improved success rates, McCloud said. The idea is being rolled out to all students.

“The hope is that this will help us on the scheduling end of things,” McCloud said.

Related: A new way to help some college students: Zero percent, no-fee loans

Texas A&M University-San Antonio is using data to better track how many students are in each major, how many new students are expected, how many students fail and need to repeat required courses and whether there is capacity to increase class enrollments, said Duane Williams, associate vice provost of student success and retention.

“We have to be making the best decisions, and we can’t make them blindly,” Williams said.

The surprising fact that departments haven’t always done that, he said, is partly because “some folks may not have received the proper training. You would think higher ed as a whole would have systems for this, but some do, some don’t. Some are still doing it old school, where they’re just going to keep something on a sheet of paper.”

That may have been enough when there seemed to be an unlimited supply of students. But as public scrutiny of universities and colleges intensifies, and with enrollment projected to decline, institutions are pressed “to help students get in and get out and with the least amount of debt as possible,” Williams said.

Improving the scheduling of required courses seems a comparatively simple way to do this, Mumford said.

“For universities that have all these goals about getting students to graduate or to get more students into STEM,” he said, “this seems like a much cheaper thing to solve than many of the other interventions they’re considering.”

Contact writer Jon Marcus at 212-678-7556, jmarcus@hechingerreport.org or jpm.82 on Signal.

This story about shortages of required courses was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for our higher education newsletter. Listen to our higher education podcast.

Education

New Jersey’s ‘Abbott districts’ are 25 years into offering free, high quality pre-K, but at least 10,000 eligible kids haven’t enrolled

This story about Abbott districts was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

UNION CITY, N.J. — By 7:30 a.m., Jackson had started rushing his father, José Bernard, to leave their house. “Dad, we’re going! We’re going, come on, let’s go.”

The 4-year-old was itching to return to his favorite place: Eugenio Maria de Hostos Center for Early Childhood Education, a burst of orange and blue on the corner of Union City’s bustling Kennedy Boulevard.

These small moments stick out for Jackson’s father. A year and a half earlier, as a young toddler coming out of daycare, Jackson was nonverbal.

“It’s life-changing, I’ll be honest with you,” said Bernard, who grew up in Union City in Hudson County. The city is home to one of the urban districts in New Jersey with universal and free preschool, created as part of a slate of remedies meant to make up for uneven funding between rich and poor districts in the state.

At the center, young voices try out vowel sounds in Spanish, English and Mandarin, present projects about fish and sea turtles, count plastic ice cream scoops and learn rules of the classroom through song.

“They are the absolute best school that I’ve ever known,” Bernard said. “It’s a chain reaction from the principal all the way down … I made the best decision for my son, 100 percent.”

Starting in the 1980s, courts hearing the landmark school funding case Abbott v. Burke sought to equalize spending across New Jersey’s schools. Districts located in areas with higher property values were able to spend more on their schools than poor urban districts could — a disparity that was found to violate the state’s constitutional requirement to provide a “thorough and efficient” education for all of New Jersey’s schoolchildren.

The Abbott litigation spawned several decisions by the state Supreme Court, one of which was a 1998 ruling that mandated free preschool for 3- and 4-year-old children in 28 of its highest-poverty urban school districts. That number has since grown to 31.

The state department of education set an ambitious goal of enrolling 90 percent of eligible children in each district, and opened classrooms in private, nonprofit and public settings in the 1999-2000 school year. At that time, New Jersey was the only state to mandate preschool, starting at age 3, for children facing social and academic risk.

“The court recognized that to get kids caught up they need to start off by somehow leveling the playing field from the very beginning, and the best way to do that was with early childhood education,” said Danielle Farrie, research director at the Newark-based Education Law Center, which represented districts for decades in the long-running case.

Related: Young children have unique needs, and providing the right care can be a challenge. Our free early childhood education newsletter tracks the issues.

As the program continued into its 25th year, researchers have found that the endeavor worked to reduce learning gaps and special education rates between rich and poor children — for those it has reached.

However, over 10,000 children eligible for the program are not enrolled, particularly 3-year-olds, according to a recent assessment of the program by The Education Law Center.

Supporters worry that the state’s recently established focus on expanding preschool throughout the state could draw attention and resources away from the early-learning program created by the Abbott litigation.

When it comes to reaching at least 90 percent of the low-income children in the 31 districts targeted by the lawsuit, “we haven’t come anywhere close to meeting those goals,” Farrie said. “To us it’s a question of priorities.”

Designed by early learning experts, the preschools were intended from the start to offer a high-quality program. Class sizes are limited to no more than 15 students, and each class has a certified teacher and an assistant. The school day is six hours, and transportation and health services are offered as needed. Teachers are paid on par with K-3 teachers in their district, and the program’s curriculum conforms to New Jersey’s standards of quality in early education.

“Our special sauce is that we provide opportunities for the families,” said Adriana Birne, director of Union City’s early childhood offerings and principal at Eugenio Maria de Hostos Center, where parents are invited in as jurors for special class projects, readers for storytime, or as guests for school plays. “We enforce the idea that it’s a collaborative effort — moms, dads, teachers, children all working together for success for their little ones.”

The preschool programs have tried to serve as many eligible kids as possible by providing slots at public schools as well as private childcare providers, Head Start programs, YMCAs and nonprofits that agree to meet the state’s standards.

By many measures, the targeted preschool program has been successful in boosting long-term academic gains for their students. The state ranks in the nation’s top 10 for child well-being and second for education after Massachusetts, based on fourth grade test scores and high school graduation rates.

However, in the 2024-25 school year the program enrolled only 34,082 kids, about 78 percent of those eligible, across public, private and nonprofit providers. Last year, only five of the 31 districts reached the 90 percent target for enrolling eligible children, compared to 18 districts in 2009-10. Enrollment has been steadily declining, a trend accelerated by the pandemic, the Education Law Center report states.

Experts say it can be difficult to find eligible kids because many have only recently moved into the state and their parents haven’t yet heard of the program through word of mouth. Some families believe 3 is too young for school, or are immigrants fearful of raids now being conducted at school sites.

A few district-run programs like Perth Amboy’s require parents to show a government-issued ID or Social Security number to enroll their children. The district enrolled only 63 percent of its eligible 3-year-olds in the 2023-24 school year. The ACLU of New Jersey has previously challenged such requirements, saying they are unconstitutional.

Programs also aren’t recruiting as aggressively as they did when the program began. Cindy Shields, who led a preschool site in Perth Amboy from 2004 to 2013 and is now a senior policy analyst for Advocates for Children of New Jersey, said she used to recruit at playgrounds, churches, laundromats, supermarkets and nail salons — anywhere families were.

Districts once advertised preschool in the plastic table settings of local restaurants, said Ellen Frede, who helped design the Abbott preschool program and ran the state’s implementation team. Frede is now co-director of the National Institute for Early Education Research, or NIEER, based at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

In its heyday, the large team of experts that formed the state pre-K office could also enforce corrective action plans for failing to reach enrollment targets, Frede said.

But during Republican Gov. Chris Christie’s administration from 2010 to 2018, pre-K was reduced to barebone levels. In 2011, New Jersey’s early childhood budget — already only a small fraction of overall education dollars in the state — was slashed 20 percent, causing recruitment efforts to dwindle.

Though funding and political support for preschool was restored under Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy — who recently signed a budget that invests about $1.3 billion in statewide preschool over the next fiscal year — funding for the state department of education’s early childhood arm overseeing the endeavor hasn’t grown in tandem.

Today, “we have a much smaller early childhood office that is actually attempting to expand this program across the entire state without that same kind of attention to detail,” said Farrie, with the Education Law Center.

Related: Pre-K at budget crossroads

While New Jersey stands out in an early childhood landscape that can be grim in terms of quality and pay, investing roughly $16,000 per pupil, high quality preschool is very costly to operate. The state-funded preschools in the districts named in the Abbott litigation require pay parity with public school teachers, yet many districts and private providers operate on low wages and razor thin profit margins. Increases in liability insurance costs for child care providers and preschools is another strain.

The state has also cut back on incentives like bonuses and college scholarships for teachers to enter the program. Such incentives were common in the early years of the state-funded program, resulting in a teaching population that is more diverse and reflective of the student body than K-12 teachers at large. In the 2024-25 school year, 22 and 25 percent of preschool teachers in the 31 districts with universal preschool were Black and Hispanic, compared to just 6 and 9 percent of K-12 educators in New Jersey, respectively.

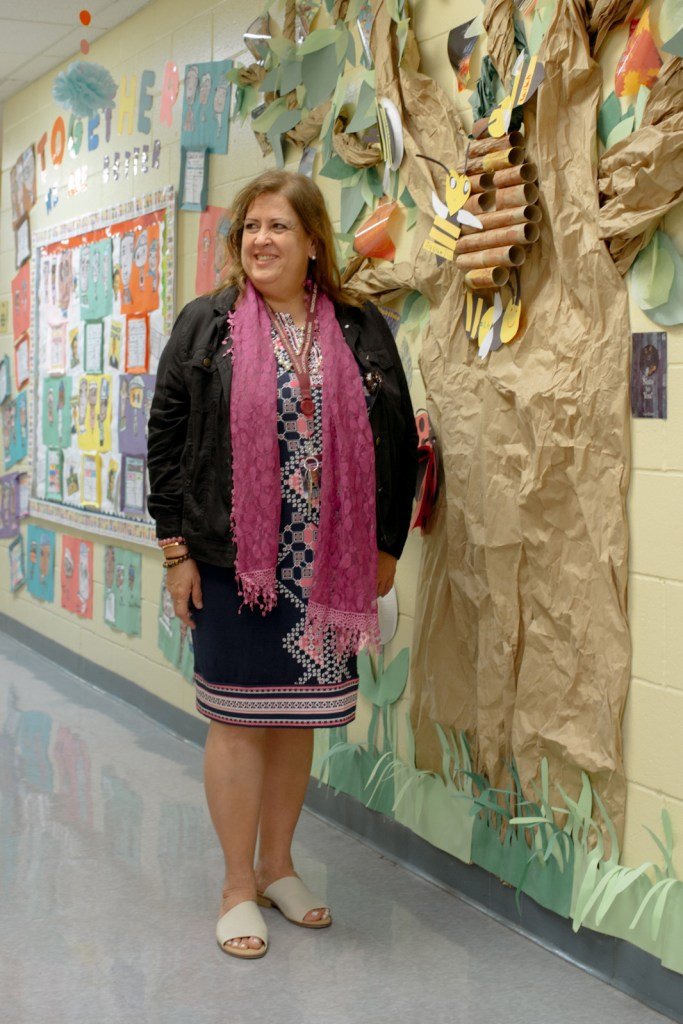

State board of education scholarships helped pay college costs for Euridice Correa, a teacher at Eugenio Maria de Hostos Center. Correa, affectionately called “La Reina” or “queen” by some parents, is Jackson’s teacher. She’s now in her 18th year as an early childhood educator.

Correa, who moved to New Jersey from Colombia at nine years old, earned degrees from New Jersey City University thanks to incentives offered in the early years of the court-mandated preschool program.

“I was very poor. I was still working as a cleaner and helping in the daycare,” she said. The state “paid for my whole B.A. and for half of my Master’s with bilingual certification.”

New Jersey, said Shields, the analyst with Advocates for Children of New Jersey, used to offer “college money, they had incentives, they had sign-on bonuses. They were giving teachers laptops, and we know that it worked. They created this beautiful diverse workforce of teachers that looked just like the children. But we don’t have that anymore.”

A spokesperson for the state department of education said that paths to bring teachers into the profession “remain a priority in New Jersey to support early childhood educators, particularly in community-based settings.” They cited the Grow NJ Kids scholarship program, which offers scholarships for family care providers and preschool teachers to get additional training.

Despite expansion and sustainability challenges, research shows the preschools created through the Abbott litigation have helped close the educational gaps that Black, Latino and low-income children were facing.

By fifth grade, students who were part of the preschool program scored higher on math, literacy and science tests than New Jersey kids who did not attend. Through 10th grade, researchers found their grade retention and special education rates were down 15 and 7 percent respectively.

Researchers found double the impact on scores for kids like Jackson who are enrolled for two years — enough to make up for a third of the achievement gap between Black and white children. Thousands of kids have entered K-12 more prepared. As a result, Union City moved its algebra offerings from ninth to seventh grade.

Related: States spending more overall on pre-K, but there are still haves and have nots

“It gives a baseline. You can change things all the way up,” said Steven Barnett, NIEER’s co-director and founder, who is now researching higher education outcomes for Abbott preschoolers. There’s evidence from other communities that quality preschools can affect children into adulthood: Oklahoma’s universal pre-K for 4-year-olds, one of the nation’s oldest, is linked to a 12 percent increase in college enrollment.

The programs have also been able to offer enrichment for their students that would otherwise be impossible to fund.

At Noah’s Ark Preschool, a private provider in Highland Park in Middlesex County, 3-year-olds hold full conversations, sharing about their trips to see family out of state or weekend plans to go to local pools. They’ve learned to write their names and read signs.

Early learning years are so much more than just learning ABCs or shapes, said founder Karen Marino. “It’s really about their independence,” she said, adding that she started Noah’s Ark after looking for affordable care for her own three children years ago, one of whom now runs the site. Her school has contracted with New Brunswick schools in Middlesex County to offer seats since the program began.

Farther north in Passaic, the nonprofit Children’s Day Preschool serves over 120 kids learning social and fine motor skills through play. With fundraising, the school, in Passaic County, was able to afford renovations, a full-time art therapist and a nurse for their community of mostly Mexican, Peruvian, Colombian, Puerto Rican and Dominican families.

Children’s Day feels for many like an extension of home, with family recipes lining the walls and bilingual instructions for parents on how to ask about their child’s day at school: “Did you learn something new? Who made you smile today? Did you help someone today or did someone help you?”

Many of their educators have been teaching at the site for 15 to 20 years. James Acosta, who attended the center as a child and is now is not a digital media assistant, said returning to work was “like seeing like aunts and uncles saying, ‘you’re so big now!’”

Abbott supporters hope more families will join the program. Parent Candy Vitale’s 6-year-old son, Mateo, is reading at a second-grade level and learning how to solve for an unknown “x” in math equations.

Vitale spent the equivalent of a monthly mortgage payment so her older daughter could attend a comparable half-day pre-K at the Jersey Shore. She learned of the offerings in Union City from her partner, whose older children had attended.

“This is the foundation of loving learning, and loving school, and feeling loved at school,” Vitale said. “Knowing that I was dropping him off every day, and he was in a place that he absolutely was enamored by — I think that there’s no price tag you can put on that.”

Contact the editor of this story, Christina Samuels, at 212-678-3635, via Signal at cas.37 or samuels@hechingerreport.org.

This story about Abbott districts was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

Education

Sparkwork Group Appoints Venkatesh N S as CTO to Drive AI-Powered Personalized Learning at SisuCare Education

SisuCare Education, part of Sparkwork Group, today announced the appointment of Venkatesh N S as Chief Technology Officer (CTO). With over 23 years of experience building and scaling technology across education, healthcare, fintech, and AI-driven platforms, Venkatesh will lead SisuCare’s technology strategy as the company accelerates its mission to deliver trusted, AI-powered, personalized learning for learners and educators worldwide.

Venkatesh’s career has been defined by building systems that empower people and creating technology that makes a difference. Over 23 years, Venkatesh has led large-scale digital transformation initiatives, architected global cloud-native solutions reaching millions of users, and built AI-powered platforms. He holds several U.S. patents in virtualization technologies and has published multiple technical papers on scalable cloud architectures and related innovations, underscoring his commitment to driving innovation in scalable, high-impact technologies. Equally important, Venkatesh is recognized for his leadership in mentoring high-performing teams, nurturing a culture of innovation, and championing human-centered design.

“These values have guided me throughout my journey, from my early days as an engineer to leading global technology teams: innovate with purpose, work together, and always keep the human at the center of the technology,” said Venkatesh. “At SisuCare, we have the opportunity to combine cutting-edge AI with the care and insight of great educators, creating adaptive learning experiences that respond in real time to each student’s needs.”

Strengthening Technology Leadership and Team Excellence

Venkatesh joins SisuCare to strengthen the technology team and provide mentorship, leadership, and strategy. As CTO, he will help shape clear priorities, support team growth, and ensure the work consistently advances SisuCare’s mission and the needs of learners and educators.

“I believe the future of education is not just about delivering content, but about delivering transformation,” Venkatesh added. “If we do this right, we won’t just be improving education, we’ll be reshaping the future of how the world learns.”

“We’re thrilled to welcome Venkatesh to SisuCare,” said Bijay Baniya, CEO of SisuCare & Sparkwork. “Venkatesh brings a rare blend of technical depth, experience operating at scale, and business leadership. His track record of building global, cloud-native AI platforms and his commitment to purposeful innovation make him the perfect leader to advance our vision for truly personalized learning. Together, we’ll empower educators, inspire learners, and set a new standard for responsible AI in education.”

Near-Term Focus Areas Under Venkatesh’s Leadership

- A scalable, cloud-native platform for adaptive, real-time learning experiences

- Responsible and transparent AI: privacy, safety, and inclusion by design

- Powerful educator tools that amplify teaching, assessment, and mentorship

- Global readiness and interoperability with institutions and partners

- A culture of innovation: mentorship, cross-functional collaboration, and rapid experimentation

About SisuCare

SisuCare Education is a California-based nursing education provider approved by the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) to deliver training for Certified Nurse Assistant (CNA) and Certified Home Health Aide (CHHA) programs, as well as offering a Director of Staff Development (DSD) certification. As one of California’s largest self-paced and hybrid CNA training programs, SisuCare meets learners where they learn best, providing opportunities to thousands of students needing access and flexible options beyond a traditional, fully in-person training model. Sisucare Education is part of Sparkwork Group, which offers global enterprise learning and education platforms to businesses. With this appointment, SisuCare strengthens its position at the intersection of education and AI, advancing its mission to prepare learners for the future of work.

Media Contact

Company Name: SisuCare Education (Sparkwork Group)

Contact Person: Bijay Baniya, CEO (Chief Executive Officer)

Email: Send Email

Phone: (213) 537-8360

City: Stanton

State: CA

Country: United States

Website: www.sisucare.com

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences3 months ago

Events & Conferences3 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoAERDF highlights the latest PreK-12 discoveries and inventions

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi