Education

Integrating artificial intelligence into medical education: a narrative systematic review of current applications, challenges, and future directions | BMC Medical Education

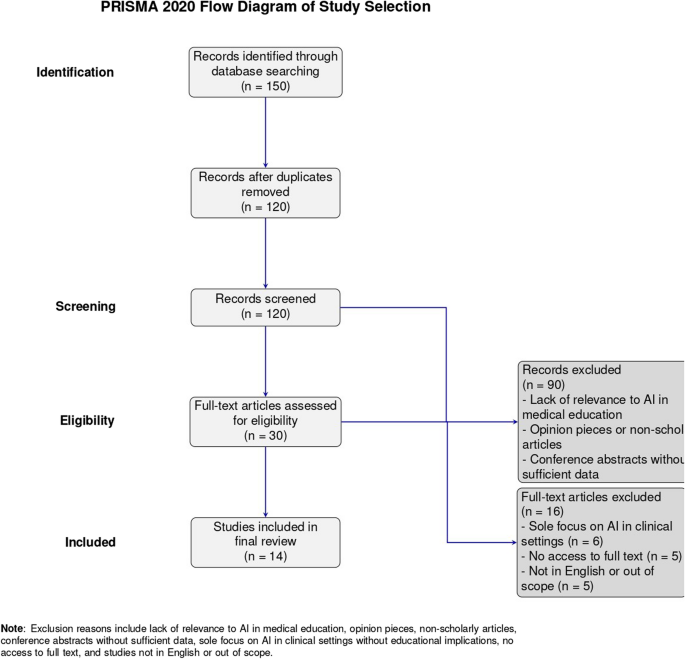

The initial search yielded a total of 150 studies across four databases. After removing duplicates, 120 unique records were screened based on titles and abstracts. Of these, 30 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Following a full-text review, 14 studies were included in the final synthesis from PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar (Fig. 1). The remaining studies were excluded for reasons including lack of educational context, absence of AI-related content, or unavailability of full text. A summary of the study selection process is presented in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

The narrative review includes 14 studies covering diverse geographic locations including the United States, India, Australia, Germany, Saudi Arabia, and multi-national collaborations. The selected studies employed a mix of methodologies: scoping reviews, narrative reviews, cross-sectional surveys, educational interventions, integrative reviews, and qualitative case studies. The target population across studies ranged from undergraduate medical students and postgraduate trainees to faculty members and in-service professionals.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) was applied across various educational contexts, including admissions, diagnostics, teaching and assessment, clinical decision-making, and curriculum development. Several studies focused on stakeholder perceptions, ethical implications, and the need for standardized curricular frameworks. Notably, interventions such as the Four-Week Modular AI Elective [13] and the Four-Dimensional AI Literacy Framework [12] were evaluated for their impact on learner outcomes.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive summary of each study, outlining country/region, study type, education level targeted, AI application domain, frameworks or interventions used, major outcomes, barriers to implementation, and ethical concerns addressed.

Risk of bias assessment

A comprehensive risk of bias assessment was conducted using appropriate tools tailored to each study design. For systematic and scoping reviews (e.g., Gordon et al. [2], Khalifa & Albadawy [8], Crotty et al. [11]), the AMSTAR 2 tool was applied, revealing a moderate risk of bias, primarily due to the lack of formal appraisal of included studies and incomplete reporting on funding sources. Observational studies such as that by Parsaiyan & Mansouri [9] were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) and showed a low risk of bias, with clear selection methods and outcome assessment. For cross-sectional survey designs (e.g., Narayanan et al. [10], Ma et al. [12], Wood et al. [14], Salih [20]), the AXIS tool was used. These showed low to moderate risk depending on sampling clarity, non-response bias, and data reporting. Qualitative and mixed-methods studies such as those by Krive et al. [13] and Weidener & Fischer [15] were appraised using a combination of the CASP checklist and NOS, showing overall low to moderate risk, particularly for their methodological rigor and triangulation. One study [19], which employed a quasi-experimental design, was evaluated using ROBINS-I and was found to have a moderate risk of bias, primarily due to concerns about confounding and deviations from intended interventions. Lastly, narrative reviews like Mondal & Mondal [17] were categorized as high risk due to their lack of systematic methodology and critical appraisal Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 14 studies were included in this systematic review, published between 2019 and 2024. These comprised a range of study designs: 5 systematic or scoping reviews, 4 cross-sectional survey studies, 2 mixed-methods or qualitative studies, 1 quasi-experimental study, 1 narrative review, and 1 conceptual framework development paper. The majority of the studies were conducted in high-income countries, particularly the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada, while others included contributions from Asia and Europe, highlighting a growing global interest in the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in medical education.

The key themes addressed across these studies included: the use of AI for enhancing clinical reasoning and decision-making skills, curriculum integration of AI tools, attitudes and readiness of faculty and students, AI-based educational interventions and simulations, and ethical and regulatory considerations in AI-driven learning. Sample sizes in survey-based studies ranged from fewer than 100 to over 1,000 participants, representing diverse medical student populations and teaching faculty.

All included studies explored the potential of AI to transform undergraduate and postgraduate medical education through improved personalization, automation of feedback, and development of clinical competencies. However, variability in methodology, focus, and outcome reporting was observed, reinforcing the importance of structured synthesis and cautious interpretation.

-

A.

Applications of AI in Medical Education

AI serves multiple educational functions. Gordon et al. identified its use in admissions, diagnostics, assessments, clinical simulations, and predictive analytics [2]. Khalifa and Albadawy reported improvements in diagnostic imaging accuracy and workflow efficiency [8]. Narrative reviews by Parsaiyan et al. [9] and Narayanan et al. [10] highlighted AI’s impact on virtual simulations, personalized learning, and competency-based education.

-

B.

Curricular innovations and interventions

Several studies introduced innovative curricular designs. Crotty et al. advocated for a modular curriculum incorporating machine learning, ethics, and governance [11], while Ma et al. proposed a Four-Dimensional Framework to cultivate AI literacy [12]. Krive et al. [13] reported significant learning gains through a four-week elective, emphasizing the value of early, practical exposure.

Studies evaluating AI-focused educational interventions primarily reported improvements in knowledge acquisition, diagnostic reasoning, and ethical awareness. For instance, Krive et al. [13] documented substantial gains in students’ ability to apply AI in clinical settings, with average quiz and assignment scores of 97% and 89%, respectively. Ma et al. highlighted enhanced conceptual understanding through their framework, though outcomes were primarily self-reported [12]. However, few studies included objective or longitudinal assessments of educational impact. None evaluated whether improvements were sustained over time or translated into clinical behavior or patient care. This reveals a critical gap and underscores the need for robust, multi-phase evaluation of AI education interventions.

-

C.

Stakeholder perceptions

Both students and faculty showed interest and concern about AI integration. Wood et al. [14] and Weidener and Fischer [15] noted a scarcity of formal training opportunities, despite growing awareness of AI’s importance. Ethical dilemmas, fears of job displacement, and insufficient preparation emerged as key concerns.

-

D.

Ethical and regulatory challenges

Critical ethical issues were raised by Mennella et al. [16] and Mondal and Mondal [17], focusing on data privacy, transparency, and patient autonomy. Multiple studies called for international regulatory standards and the embedding of AI ethics within core curricula.

While several reviewed studies acknowledged the importance of ethical training in AI, the discussion of ethics often remained surface-level. A more critical lens reveals deeper tensions that must be addressed in AI-integrated medical education. One such tension lies between technological innovation and equity AI tools, if not designed and deployed with care, risk widening disparities by favoring data-rich, high-resource settings while neglecting underrepresented populations. Moreover, AI’s potential to entrench existing biases—due to skewed training datasets or uncritical deployment of algorithms—poses a threat to fair and inclusive healthcare delivery.

Another pressing concern is algorithmic opacity. As future physicians are expected to work alongside AI systems in high-stakes clinical decisions, the inability to fully understand or challenge these systems’ inner workings raises accountability dilemmas and undermines trust. Educational interventions must therefore go beyond theoretical awareness and cultivate critical engagement with the socio-technical dimensions of AI, emphasizing ethical reasoning, bias recognition, and equity-oriented decision-making.

-

E.

Barriers to implementation

Implementation hurdles included limited empirical evidence [18], infrastructural constraints [19], context-specific applicability challenges [20], and an over-reliance on conceptual frameworks [10]. The lack of unified teaching models and outcome-based assessments remains a significant obstacle.

These findings informed the creation of a conceptual framework for integrating artificial intelligence into medical education, depicted in Fig. 1. A cross-theme synthesis revealed that while AI integration strategies were broadly similar across countries, their implementation success varied significantly by geographic and economic context. High-income countries (e.g., USA, Australia, Germany) demonstrated more comprehensive curricular pilots, infrastructure support, and faculty readiness, whereas studies from LMICs (e.g., India, Saudi Arabia) emphasized conceptual interest but lacked institutional capacity and access to AI technologies. Contextual barriers such as resource limitations, cultural sensitivity, and institutional inertia appeared more pronounced in LMIC settings, influencing the feasibility and depth of AI adoption in medical education.

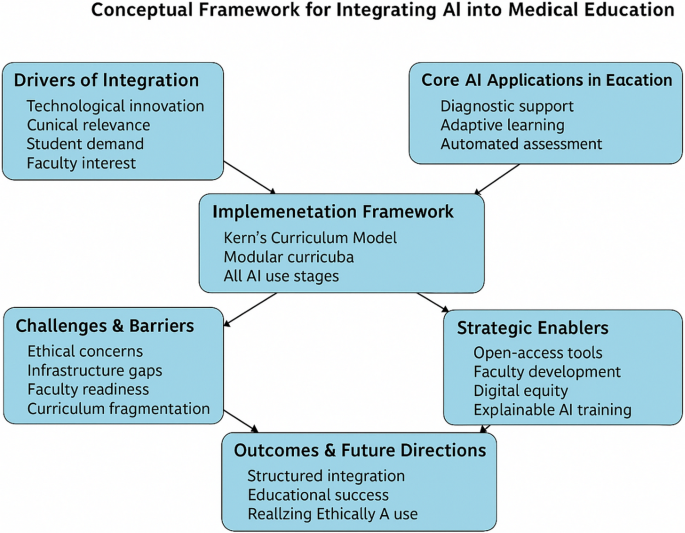

Based on the five synthesized themes, we developed a Comprehensive Framework for the Strategic Integration of AI in Medical Education (Fig. 2). This model incorporates components such as foundational AI literacy, ethical preparedness, faculty development, curriculum redesign, and contextual adaptability. It builds on and extends existing models such as the FACETS framework, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), and the Diffusion of Innovation theory. Unlike FACETS, which primarily categorizes existing studies, our framework is action-oriented and aligned with Kern’s curriculum development process, making it suitable for practical implementation. Compared to TAM and Diffusion of Innovation, which focus on user behavior and adoption dynamics, our model integrates educational design elements with implementation feasibility across diverse economic and institutional settings.

Table 3 shows a comparative synthesis of included studies evaluating AI integration in medical and health professions education using Kern’s six-step curriculum development framework. The analysis reveals that most studies effectively identify the need for AI literacy (Step 1) and conduct some form of needs assessment (Step 2), often through surveys, literature reviews, or scoping exercises. However, only a subset of studies explicitly define measurable educational goals and objectives (Step 3), and even fewer describe detailed instructional strategies (Step 4) or implement their proposed curricula (Step 5). Evaluation and feedback mechanisms (Step 6) were rarely reported, and when included, they were typically limited to short-term student feedback or pre-post knowledge assessments. Longitudinal evaluations and outcome-based assessments remain largely absent. The findings underscore a critical implementation gap and emphasize the need for structured, theory-informed, and empirically evaluated AI education models tailored to medical and allied health curricula.

This conceptual model is informed by thematic synthesis and integrates principles from existing frameworks (FACETS, TAM, Diffusion of Innovation) while aligning with Kern’s six-step approach for curriculum design.

Education

Parents in England to pay more for school lunches as caterers blame rising costs | School meals

Parents across England are facing higher prices for school lunches as the new school year begins, with caterers blaming the government’s national insurance increase alongside rising food and energy costs.

Lunch providers say increases in staffing costs, including employer national insurance contributions announced by the chancellor last year, have added “significant extra pressure” to their budgets.

Food price inflation is also driving costs higher, pushing consumer prices above forecasts this summer. Prices for food and non-alcoholic drinks rose 4.9% in the year to July and are now 37% higher than five years ago, according to data from the Office for National Statistics.

Letters sent to parents informing them of price rises acknowledged the strain on families but said changes were unavoidable if catering services were to remain viable.

At Coleham primary in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, meals will rise by 10p a day to £2.60 from September 2025 because of “rising operational costs”. Bridge Hall primary in Stockport, Greater Manchester, said charges would rise by 8p to £2.73 – a 3.1% increase “in line with UK inflation”. Fernhurst Junior in Portsmouth confirmed a new daily rate of £2.86, and West Vale Academy in Halifax £2.60. Kingskerswell Church of England primary school in Newton Abbott raised costs to £2.75, up by 30p.

Ministers have promised to widen eligibility for free meals from 2026 but schools have said they cannot wait that long.

About a quarter of pupils in Englandcurrently qualify for free school meals, but campaigners say the government’s £2.61-a-meal funding is no longer sufficient, leaving schools to plug the gap.

“All schools will be navigating the impact of rapidly rising food costs,” said Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the school leaders’ union the National Association of Head Teachers. “Sometimes school dinners are the only reliable nutritious meal a child will get that day, so for this to be of worse quality or more expensive is extremely concerning.”

Judith Gregory, chair of LACA, which represents public and private sector caterers in schools, said they were “doing everything possible to shield families by streamlining menus, adapting recipes and finding efficiencies”.

But Gregory said caterers’ efforts were not enough, and schools were having to raise costs for others to cover the funding shortfall.

“Food inflation has driven up the cost of school meals by more than 20% since 2020,” she said. “Without urgent action to raise funding to at least £3.45 per meal, schools will be forced to reduce options or introduce less costly ingredients, while families just above the free school meal threshold face higher charges.”

Gregory said the recent increase in employer’s national insurance as well as annual pay increases for workers were adding “significant extra pressure” on top of already steep rises in food costs.

Barbara Crowther, the children’s food campaign manager at Sustain, a group advocating for food and agriculture policies and practices that enhance health and welfare, said the “true cost of a healthy, sustainable school meal” was now closer to £3-£3.20, depending on the size of schools and catering operations.

Campaigners argue that the higher charges will disproportionately affect low-income families, with many falling just below the threshold for free school meals.

“School leaders are deeply worried,” said Whiteman. “They are seeing more families struggling and more children living in poverty – child hunger is a real concern. There is only so long schools can keep swallowing the increases. For many, putting up the cost of meals is now the only option.”

The Department for Education said the government has taken “a historic step to tackle the stain of child poverty, offering free school meals to every child from a household that claims universal credit from the start of the 2026 school year”.

A spokesperson added: “The new entitlement will be fully funded and lift 100,000 children entirely out of poverty. To make sure meals are high-quality and nutritious, the government is working with experts to revise the school food standards, and we will continue to work closely with the sector to keep meal rates under review.”

The Guardian was unable to reach schools for comment.

Education

Meet the three-year-olds helping anxious teens spend more time in school

BBC

BBCSiena never thought she’d be taking lessons in communication and confidence from a three-year-old.

She is part of a scheme that pairs teenagers with toddlers from a local nursery in a bid to help increase school attendance and engagement.

The 13-year-old says she had a “lot of anxiety” so would never be in school, but “coming here has taught me more about how to communicate and be more confident and it’s funny a toddler is teaching us things.”

While she didn’t think the project would help increase her attendance, it has actually more than doubled.

“It’s really helped me,” she says. “The toddler I’m paired with has grown so much and it makes me so happy to see,” she tells the BBC’s Morning Live.

Morning Live returns on Monday at 0930am. Watch this and more here.

As the summer holiday ends and the new school year begins, many parents will be worrying about their child’s attendance and engagement.

The issue of school avoidance is a big one and one charity has created this mentoring programme with its research suggesting that a disengaged teenager having responsibility for a younger child in a controlled setting can have a positive impact on their engagement with school and learning.

Since the pandemic, school absence has almost doubled – in the 2024/25 academic year, 17.79% of pupils were persistently absent meaning they missed 10% or more school sessions.

Data shows that just 10 days of absence can halve the chance of a student getting at least a grade 5 in English and Maths.

Miller, 12, another pupil participating in the scheme says he struggles to stay in class because he has a lot of energy, but that the sessions have helped him focus more on his school work.

“I was a bit nervous and it took me two weeks to say yes to the project as I was really shy.”

Miller has been paired with three-year-old Andrew and says they are now really close.

“When he sees me he runs up to me and gives me a hug.”

As well as developing his confidence, Miller adds that the sessions have made him feel calmer and less energetic.

Sam Marcus is the director of services at Power2, the charity that runs this scheme, currently only in London and Manchester.

It offers various mentoring programmes to children of all ages and over the years has helped 27,000 children and young people to re-engage with school.

This particular project works across a 16-week period where teenagers visit a local nursery once a week and mentor a child.

The pairing is well thought out – “it’s often based on personalities so a really vibrant toddler might be paired with a shy teenager or a timid toddler is matched with a boisterous teen which helps create a much softer side to them.”

The aim is that the bond between the toddler and teen will help build confidence and accountability that encourages them to then turn up to lessons and “a sense of responsibility to young people who often aren’t given those positions”.

“If a child is disruptive in class, they often aren’t given those opportunities to prove themselves to be more than that,” she says.

“We help the teen become a positive role model for that child,” she adds. The teenagers also have reflective sessions after the nursery visit to learn more about building healthy relationships and positive attitudes.

According to Power2, 78% young people on the scheme improve their attitude to learning and 83% of them have improved self esteem.

Often the toddler also has additional needs such as speech and language delays or difficulty making friends and Lisa, who teaches at one of the nursery’s involved in the project says it has a big impact on the children.

“They love having that special person each Friday,” she says. “It’s lovely to see them having that one to one time and the kids running up hugging the teens every week.”

How can you help your child with attendance?

This scheme is one small programme aiming to help with the very complex issue of school advoidance.

The Department for Education provides guidance on what to do if your child is struggling to attend school.

Dr Weisberg, a consultant clinical psychologist who works with young people who feel disconnected from their education, says often children find it hard to engage with education because “there are lots of rules at school and none of them are under the kid’s control”.

In contrast, this programme “gives them a responsibility and empowerment to learn from what works and what doesn’t and they feel like they are making a real difference”.

He gives three tips on how parents can work with their child to improve their attendance:

- Raise it with the school – “Make sure the school are on the same page and there are lots of charities and support available to make things better.”

- Give the child agency – “Be available. I recommend parents spend at least 10 minutes a day with each child without distractions like screens or phones.”

- Follow their lead – With younger children, it’s important for parents to play with them and follow their lead which can “foster healthy relationships and confidence”.

Sue Armstrong, a clinical service manager at relationship support charity Relate, says other ways to support your child through school anxiety and avoidance include:

- Avoid blaming yourself and your child – “It’s important to try not to feel guilty or that this is somehow your fault”.

- Look forward to positive things – “Continuing ‘normal’ family events will help all of you. Finding time, when you can, for your own interests, as a couple and individually, is vital”.

- Accept there will be ups and downs – “You may feel you’re being pulled in every direction, having to keep a job going and support your child when they may be feeling very anxious and confused, that there’s no space left for you”.

Education

AI Has Broken High School and College

This is Atlantic Intelligence, a newsletter in which our writers help you wrap your mind around artificial intelligence and a new machine age. Sign up here.

Another school year is beginning—which means another year of AI-written essays, AI-completed problem sets, and, for teachers, AI-generated curricula. For the first time, seniors in high school have had their entire high-school careers defined to some extent by chatbots. The same applies for seniors in college: ChatGPT released in November 2022, meaning unlike last year’s graduating class, this year’s crop has had generative AI at its fingertips the whole time.

My colleagues Ian Bogost and Lila Shroff both recently wrote articles about these students and the state of AI in education. (Ian, a university professor himself, wrote about college, while Lila wrote about high school.) Their articles were striking: It is clear that AI has been widely adopted, by students and faculty alike, yet the technology has also turned school into a kind of free-for-all.

I asked Lila and Ian to have a brief conversation about their work—and about where AI in education goes from here.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Lila Shroff: We’re a few years into AI in schools. Is the conversation maturing or changing in some way at universities?

Ian Bogost: Professors are less surprised that it exists, but there is maybe a bit of a blind spot to the state of adoption among students. I saw a panic in 2022, 2023—like, Oh my God, this can do anything. Or at least there were questions. Can this do everything? How much is my class at risk? Now I think there’s more of a sense of, Well, this thing still exists, but we have time. We don’t have to worry about it right away. And that might actually be a worse reaction than the original.

Lila: The blind-spot language rings true to the high-school environment too. I spoke to some high schoolers—granted this was quite a small sample—but basically it sounds like everybody is using this all the time for everything.

Ian: Not just for school, right? Anything they want to do, they’re asking ChatGPT now.

Lila: I was a sophomore in college when ChatGPT came out, so I witnessed some of this firsthand. There was much more anxiety—it felt like the rules were unclear. And I think both of our stories touched on the fact that for this incoming class of high-school and college seniors, they’ve barely had any of those four years without ChatGPT. Whatever sort of stigma or confusion that might have been there in earlier years is fading, and it’s becoming very much default and normalized.

Ian: Normalization is the thing that struck me the most. That is not a concept that I think the teachers have wrapped their heads around. Teachers and faculty also have been adopting AI carefully or casually—or maybe even in a more professional way, to write articles or letters of recommendation, which I’ve written about. There’s still this sense that it’s not really a part of their habit.

Lila: I looked into teachers at the K–12 level for the article I wrote. Three in 10 teachers are using AI weekly in some way.

Ian: Some kind of redesign of educational practice might be required, which is easy for me to say in an article. Instead of an answer, I have an approach to thinking about the answer that has been bouncing around in my brain. Are you familiar with the concept in software development called technical debt? In the software world, you make the decision about how to design or implement a system that feels good and right at the time. And maybe you know it’s going to be a bad idea in the long run, but for now, it makes sense and it is convenient. But you never get around to really making it better later on, and so you have all these nonoptimal aspects of your infrastructure.

That’s the state I feel like we’re in, at least in the university. It’s a little different in high school, especially in public high school, with these different regulatory regimes at work. But we accrued all this pedagogical debt, and not just since AI—there are aspects of teaching that we ought to be paying more attention to or doing better, like, this class needs to be smaller, or these kinds of assignments don’t work unless you have a lot of hands-on iterative feedback. We’ve been able to survive under the weight of pedagogical debt, and now something snapped. AI entered the scene and all of those bad or questionable—but understandable—decisions about how to design learning experiences are coming home to roost.

Lila: I agree that AI is a breaking point in education. One answer that seems to be emerging at the high-school level is a more practical, skills-based education. The College Board, for instance, has announced two new AP courses—AP Business and AP Cybersecurity. But there’s another group of people who are really concerned about how overreliance on these tools erodes critical-thinking skills, and maybe that means everyone should go read the classics and write their essays in cursive handwriting.

Ian: My young daughter has been going to this set of classes outside of school where she learned how to wire an outlet. We used to have shop class and metal class, and you could learn a trade, or at least begin to, in high school. A lot of that stuff has been disinvested. We used to touch more things. Now we move symbols around, and that’s kind of it.

I wonder if this all-or-nothing nature of AI use has something to do with that. If you had a place in your day as a high-school or college student where you just got to paint, or got to do on-the-ground work in the community, or apply the work you did in statistics class to solve a real-world problem—maybe that urge to just finish everything as rapidly as possible so you can get onto the next thing in your life would be less acute. The AI problem is a symptom of a bigger cultural illness, in a way.

Lila: Students are using AI exactly as it has been designed, right? They’re just making themselves more productive. If they were doing the same thing in an office, they might be getting a bonus.

Ian: Some of the students I talked to said, Your boss isn’t going to care how you get things done, just that they get done as effectively as possible. And they’re not wrong about that.

Lila: One student I talked to said she felt there was really too much to be done, and it was hard to stay on top of it all. Her message was, maybe slow down the pace of the work and give students more time to do things more richly.

Ian: The college students I talk to, if you slow it all down, they’re more likely to start a new club or practice lacrosse one more day a week. But I do love the idea of a slow-school movement to sort of counteract AI. That doesn’t necessarily mean excluding AI—it just means not filling every moment of every day with quite so much demand.

But you know, this doesn’t feel like the time for a victory of deliberateness and meaning in America. Instead, it just feels like you’re always going to be fighting against the drive to perform even more.

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences3 months ago

Events & Conferences3 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months ago

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months agoDonald Trump suggests US government review subsidies to Elon Musk’s companies

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoAstrophel Aerospace Raises ₹6.84 Crore to Build Reusable Launch Vehicle