Ethics & Policy

How governments are driving AI adoption for economic growth

Around the world, policymakers are recognising artificial intelligence’s immense potential to reshape economies, transform industries, and strengthen global competitiveness.

While generative AI chatbots and image generators have captured the public’s attention, these tools are just a fraction of the sweeping economic transformation AI is poised to catalyse through increasing labour productivity, improving public services, and accelerating scientific progress.

However, realising these benefits demands not only continued technological advancement but also widespread adoption and adaptation across all sectors of the economy. History suggests that countries that gain the most from innovation are not necessarily those that invent technologies first, but rather those that deploy them most effectively.

Today, nearly 70 countries have adopted national AI strategies and policies. While many are still in the early stages of translating these strategies into action, a select group are emerging as AI Pioneers, moving beyond policy blueprints to make tangible investments in AI development and adoption. Google’s newly released report, AI Pioneers: How Countries are Seizing the AI Opportunity, delves into how leading countries are navigating this pivotal moment.

The report explores how countries are accelerating AI adoption by building across the three pillars of an AI Opportunity Agenda: (1) building robust AI infrastructure; (2) developing a skilled workforce; and (3) fostering a supportive policy framework. Progress across all three is essential for attracting the investments needed to build the technical foundation for broad AI adoption.

Pillar 1: Building AI infrastructure

Just as past economic revolutions relied on foundational infrastructure – canals, railways, or electricity grids – the AI era demands a new digital and physical backbone. This means investing in the infrastructure that powers AI development and deployment: high-speed internet, data centres and systems, and new energy solutions.

- Embracing cloud-first policies. Cloud computing provides an essential foundation for harnessing AI’s power. Its vast computational resources, scalable data storage, and advanced data management and analysis capabilities are crucial for AI applications. Governments are directing public sector agencies to prioritise cloud-based IT infrastructure and services over on-premise solutions, recognising the cloud’s fundamental role in enabling AI capabilities.

- Attracting investment in new data centres and cloud regions. McKinsey projects that global demand for data centre capacity will more than triple by 2030, primarily fuelled by AI. Governments are implementing a range of approaches to encourage this vital infrastructure investment, including streamlining approval processes, creating incentives for renewable energy, and offering tax exemptions.

- Strengthening connectivity: Alongside data centres, robust connectivity through subsea and terrestrial cables is essential for the fast and reliable data transfers needed to support AI applications. Initiatives like Google’s Pacific Connect and Africa Connect are examples of private sector efforts to build this global connectivity, linking continents and facilitating the flow of data necessary for AI training and deployment.

- Unlocking energy solutions. Powering AI demands significant energy. Collaboration between government and industry is key to expanding electricity infrastructure capacity, which can drive economic growth and competitiveness while helping to meet decarbonisation goals. Several governments are liberalising their electricity markets to reduce costs, enhance reliability, and facilitate the interconnection of new clean energy resources.

- Ensuring security and resilience. Governments are establishing partnerships with tech companies and security experts to safeguard AI systems from cyberattacks and equip critical infrastructure defenders with cutting-edge AI tools to support their mission.

Pillar 2: Developing a skilled workforce

Building an AI-ready workforce requires a collaborative effort from governments, the private sector, and educational institutions. This will require cultivating AI fluency in three areas: (1) ensuring foundational AI skills for all workers and students; (2) enabling governments, traditional industries, and small businesses to use and adapt AI tools effectively; and (3) developing the deep technical expertise needed to advance AI technology and shape its evolution. Over the past year, some countries have taken important steps in this direction:

- Leading by example through government adoption: Governments are setting a precedent by ensuring public sector workers gain essential AI skills and deploying AI tools across diverse government functions and public service use cases.

- Integrating AI literacy into primary education. Many governments are integrating AI literacy and critical thinking into school curricula and scaling personalised learning initiatives using AI.

- Incorporating AI curriculum at universities. To meet rising demand for AI expertise, universities in some countries are expanding AI programmes, often partnering with the private sector to develop specialised curricula.

- Developing certified credentials for AI skills. As technological change accelerates, it will become more important for people to learn skills quickly and earn well-recognised credentials. Through the Career Certificates programme, Google is boosting on-demand training for in-demand tech skills globally, collaborating with governments and more than 550 universities across Latin America to offer a continuously updated portfolio of learning resources to ensure students are ready to seize the opportunities created by new technologies.

- Empowering SMEs with AI: Governments are establishing platforms and programmes to help small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) explore AI use cases, test applications, and create internal AI talent.

Pillar 3: Fostering a supportive policy framework

A supportive policy environment is critical to AI innovation and investment. Governments seek to prevent AI’s misuse, but they must also guard against “missed uses,” or lost opportunities to use AI for significant social and economic benefit. Policymakers can balance both goals and encourage responsible innovation by avoiding actions that could stifle innovation, create barriers for startups, slow R&D, or hinder AI’s potential to address major challenges in areas such as healthcare and climate change.

- Risk-based approaches to AI. Many jurisdictions are adopting risk-based approaches to AI, recognising that policies should be calibrated to the specific risks associated with different AI applications, while also considering the opportunity costs of not deploying AI for societal benefit.

- Codes of conduct and guidelines. A growing number of economies publish codes of conduct, principles, and standards to promote responsible AI use across supply chains and commercial ecosystems. They provide developers with crucial guidance while remaining flexible in a rapidly evolving technological landscape.

- Fair use and text & data mining (TDM) exceptions: Several jurisdictions, including the US, Israel, Japan, Singapore, and the EU have recognised the importance of copyright frameworks that allow for the use of protected material by researchers and innovators under certain circumstances – often referred to as limitations and exceptions – without requiring permission from the copyright holder.

- Competitiveness Assessments. To maximise AI’s potential, many governments are actively evaluating and calibrating their regulatory frameworks to attract investment and weigh the impact of regulation on economic competitiveness.

Attracting AI Investment

Making progress on all three pillars is essential for attracting the investments needed to build the technical foundation for broad AI adoption. Attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) is particularly crucial for countries that lack the capital or technical expertise necessary to develop AI infrastructure independently.

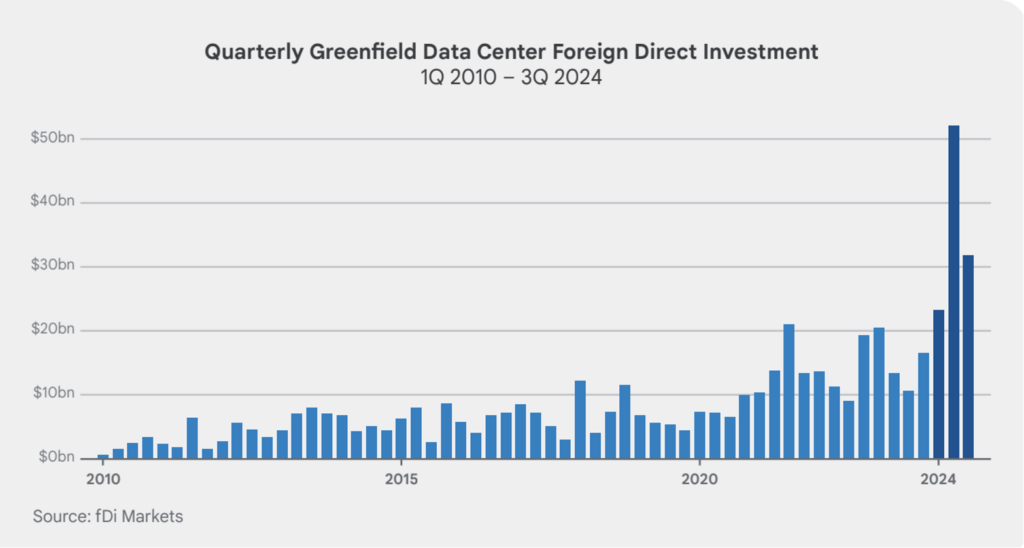

Over the past five years, foreign direct investment (FDI) in AI infrastructure has surged globally, despite overall FDI remaining sluggish. In 2024, greenfield FDI in data centres reached $144 billion, about 9% of total global FDI. These investments increasingly flow beyond traditional investment hubs to emerging markets and regions like Northumberland in the UK and the US Rust Belt.

While not every country needs its own dedicated data centre to harness the benefits of AI, investment in data centres can spark local economic development in areas like network infrastructure, specialised manufacturing (e.g., server hardware), and the expansion of energy capacity.

Many data centre projects incorporate training programmes to help local communities acquire the skills needed to work with advanced technologies. For example, Google’s most recent data centre investments in Mexico, Uruguay, Thailand, South Africa, and Malaysia all involve training programmes in partnership with local education institutions and training centres.

Countries with a strong business climate and reliable institutions typically attract higher levels of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). This is especially true for AI infrastructure, which involves large, immovable assets. Companies searching for investment opportunities gravitate toward countries with policies that encourage innovation, offer clear and predictable tax policies, and provide reliable, cost-effective energy solutions — all crucial factors in creating a favourable environment for technology advancement.

Charting the Course for AI Prosperity

By cultivating an ecosystem where businesses can confidently invest, innovate, and partner, governments that build across the three AI Opportunity pillars can catalyse the rapid development and adoption of AI. Ultimately, these efforts will determine which societies reap the benefits from this transformational technology.

The post How governments are driving AI adoption for economic growth appeared first on OECD.AI.

Ethics & Policy

AI and ethics – what is originality? Maybe we’re just not that special when it comes to creativity?

I don’t trust AI, but I use it all the time.

Let’s face it, that’s a sentiment that many of us can buy into if we’re honest about it. It comes from Paul Mallaghan, Head of Creative Strategy at We Are Tilt, a creative transformation content and campaign agency whose clients include the likes of Diageo, KPMG and Barclays.

Taking part in a panel debate on AI ethics at the recent Evolve conference in Brighton, UK, he made another highly pertinent point when he said of people in general:

We know that we are quite susceptible to confident bullshitters. Basically, that is what Chat GPT [is] right now. There’s something reminds me of the illusory truth effect, where if you hear something a few times, or you say it here it said confidently, then you are much more likely to believe it, regardless of the source. I might refer to a certain President who uses that technique fairly regularly, but I think we’re so susceptible to that that we are quite vulnerable.

And, yes, it’s you he’s talking about:

I mean all of us, no matter how intelligent we think we are or how smart over the machines we think we are. When I think about trust, – and I’m coming at this very much from the perspective of someone who runs a creative agency – we’re not involved in building a Large Language Model (LLM); we’re involved in using it, understanding it, and thinking about what the implications if we get this wrong. What does it mean to be creative in the world of LLMs?

Genuine

Being genuine, is vital, he argues, and being human – where does Human Intelligence come into the picture, particularly in relation to creativity. His argument:

There’s a certain parasitic quality to what’s being created. We make films, we’re designers, we’re creators, we’re all those sort of things in the company that I run. We have had to just face the fact that we’re using tools that have hoovered up the work of others and then regenerate it and spit it out. There is an ethical dilemma that we face every day when we use those tools.

His firm has come to the conclusion that it has to be responsible for imposing its own guidelines here to some degree, because there’s not a lot happening elsewhere:

To some extent, we are always ahead of regulation, because the nature of being creative is that you’re always going to be experimenting and trying things, and you want to see what the next big thing is. It’s actually very exciting. So that’s all cool, but we’ve realized that if we want to try and do this ethically, we have to establish some of our own ground rules, even if they’re really basic. Like, let’s try and not prompt with the name of an illustrator that we know, because that’s stealing their intellectual property, or the labor of their creative brains.

I’m not a regulatory expert by any means, but I can say that a lot of the clients we work with, to be fair to them, are also trying to get ahead of where I think we are probably at government level, and they’re creating their own frameworks, their own trust frameworks, to try and address some of these things. Everyone is starting to ask questions, and you don’t want to be the person that’s accidentally created a system where everything is then suable because of what you’ve made or what you’ve generated.

Originality

That’s not necessarily an easy ask, of course. What, for example, do we mean by originality? Mallaghan suggests:

Anyone who’s ever tried to create anything knows you’re trying to break patterns. You’re trying to find or re-mix or mash up something that hasn’t happened before. To some extent, that is a good thing that really we’re talking about pattern matching tools. So generally speaking, it’s used in every part of the creative process now. Most agencies, certainly the big ones, certainly anyone that’s working on a lot of marketing stuff, they’re using it to try and drive efficiencies and get incredible margins. They’re going to be on the race to the bottom.

But originality is hard to quantify. I think that actually it doesn’t happen as much as people think anyway, that originality. When you look at ChatGPT or any of these tools, there’s a lot of interesting new tools that are out there that purport to help you in the quest to come up with ideas, and they can be useful. Quite often, we’ll use them to sift out the crappy ideas, because if ChatGPT or an AI tool can come up with it, it’s probably something that’s happened before, something you probably don’t want to use.

More Human Intelligence is needed, it seems:

What I think any creative needs to understand now is you’re going to have to be extremely interesting, and you’re going to have to push even more humanity into what you do, or you’re going to be easily replaced by these tools that probably shouldn’t be doing all the fun stuff that we want to do. [In terms of ethical questions] there’s a bunch, including the copyright thing, but there’s partly just [questions] around purpose and fun. Like, why do we even do this stuff? Why do we do it? There’s a whole industry that exists for people with wonderful brains, and there’s lots of different types of industries [where you] see different types of brains. But why are we trying to do away with something that allows people to get up in the morning and have a reason to live? That is a big question.

My second ethical thing is, what do we do with the next generation who don’t learn craft and quality, and they don’t go through the same hurdles? They may find ways to use {AI] in ways that we can’t imagine, because that’s what young people do, and I have faith in that. But I also think, how are you going to learn the language that helps you interface with, say, a video model, and know what a camera does, and how to ask for the right things, how to tell a story, and what’s right? All that is an ethical issue, like we might be taking that away from an entire generation.

And there’s one last ‘tough love’ question to be posed:

What if we’re not special? Basically, what if all the patterns that are part of us aren’t that special? The only reason I bring that up is that I think that in every career, you associate your identity with what you do. Maybe we shouldn’t, maybe that’s a bad thing, but I know that creatives really associate with what they do. Their identity is tied up in what it is that they actually do, whether they’re an illustrator or whatever. It is a proper existential crisis to look at it and go, ‘Oh, the thing that I thought was special can be regurgitated pretty easily’…It’s a terrifying thing to stare into the Gorgon and look back at it and think,’Where are we going with this?’. By the way, I do think we’re special, but maybe we’re not as special as we think we are. A lot of these patterns can be matched.

My take

This was a candid worldview that raised a number of tough questions – and questions are often so much more interesting than answers, aren’t they? The subject of creativity and copyright has been handled at length on diginomica by Chris Middleton and I think Mallaghan’s comments pretty much chime with most of that.

I was particularly taken by the point about the impact on the younger generation of having at their fingertips AI tools that can ‘do everything, until they can’t’. I recall being horrified a good few years ago when doing a shift in a newsroom of a major tech title and noticing that the flow of copy had suddenly dried up. ‘Where are the stories?’, I shouted. Back came the reply, ‘Oh, the Internet’s gone down’. ‘Then pick up the phone and call people, find some stories,’ I snapped. A sad, baffled young face looked back at me and asked, ‘Who should we call?’. Now apart from suddenly feeling about 103, I was shaken by the fact that as soon as the umbilical cord of the Internet was cut, everyone was rendered helpless.

Take that idea and multiply it a billion-fold when it comes to AI dependency and the future looks scary. Human Intelligence matters

Ethics & Policy

Preparing Timor Leste to embrace Artificial Intelligence

UNESCO, in collaboration with the Ministry of Transport and Communications, Catalpa International and national lead consultant, jointly conducted consultative and validation workshops as part of the AI Readiness assessment implementation in Timor-Leste. Held on 8–9 April and 27 May respectively, the workshops convened representatives from government ministries, academia, international organisations and development partners, the Timor-Leste National Commission for UNESCO, civil society, and the private sector for a multi-stakeholder consultation to unpack the current stage of AI adoption and development in the country, guided by UNESCO’s AI Readiness Assessment Methodology (RAM).

In response to growing concerns about the rapid rise of AI, the UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence was adopted by 194 Member States in 2021, including Timor-Leste, to ensure ethical governance of AI. To support Member States in implementing this Recommendation, the RAM was developed by UNESCO’s AI experts without borders. It includes a range of quantitative and qualitative questions designed to gather information across different dimensions of a country’s AI ecosystem, including legal and regulatory, social and cultural, economic, scientific and educational, technological and infrastructural aspects.

By compiling comprehensive insights into these areas, the final RAM report helps identify institutional and regulatory gaps, which can assist the government with the necessary AI governance and enable UNESCO to provide tailored support that promotes an ethical AI ecosystem aligned with the Recommendation.

The first day of the workshop was opened by Timor-Leste’s Minister of Transport and Communication, H.E. Miguel Marques Gonçalves Manetelu. In his opening remarks, Minister Manetelu highlighted the pivotal role of AI in shaping the future. He emphasised that the current global trajectory is not only driving the digitalisation of work but also enabling more effective and productive outcomes.

Ethics & Policy

Experts gather to discuss ethics, AI and the future of publishing

Publishing stands at a pivotal juncture, said Jeremy North, president of Global Book Business at Taylor & Francis Group, addressing delegates at the 3rd International Conference on Publishing Education in Beijing. Digital intelligence is fundamentally transforming the sector — and this revolution will inevitably create “AI winners and losers”.

True winners, he argued, will be those who embrace AI not as a replacement for human insight but as a tool that strengthens publishing’s core mission: connecting people through knowledge. The key is balance, North said, using AI to enhance creativity without diminishing human judgment or critical thinking.

This vision set the tone for the event where the Association for International Publishing Education was officially launched — the world’s first global alliance dedicated to advancing publishing education through international collaboration.

Unveiled at the conference cohosted by the Beijing Institute of Graphic Communication and the Publishers Association of China, the AIPE brings together nearly 50 member organizations with a mission to foster joint research, training, and innovation in publishing education.

Tian Zhongli, president of BIGC, stressed the need to anchor publishing education in ethics and humanistic values and reaffirmed BIGC’s commitment to building a global talent platform through AIPE.

BIGC will deepen academic-industry collaboration through AIPE to provide a premium platform for nurturing high-level, holistic, and internationally competent publishing talent, he added.

Zhang Xin, secretary of the CPC Committee at BIGC, emphasized that AIPE is expected to help globalize Chinese publishing scholarships, contribute new ideas to the industry, and cultivate a new generation of publishing professionals for the digital era.

Themed “Mutual Learning and Cooperation: New Ecology of International Publishing Education in the Digital Intelligence Era”, the conference also tackled a wide range of challenges and opportunities brought on by AI — from ethical concerns and content ownership to protecting human creativity and rethinking publishing values in higher education.

Wu Shulin, president of the Publishers Association of China, cautioned that while AI brings major opportunities, “we must not overlook the ethical and security problems it introduces”.

Catriona Stevenson, deputy CEO of the UK Publishers Association, echoed this sentiment. She highlighted how British publishers are adopting AI to amplify human creativity and productivity, while calling for global cooperation to protect intellectual property and combat AI tool infringement.

The conference aims to explore innovative pathways for the publishing industry and education reform, discuss emerging technological trends, advance higher education philosophies and talent development models, promote global academic exchange and collaboration, and empower knowledge production and dissemination through publishing education in the digital intelligence era.

yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn

-

Funding & Business1 week ago

Kayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Jobs & Careers1 week ago

Mumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Mergers & Acquisitions1 week ago

Donald Trump suggests US government review subsidies to Elon Musk’s companies

-

Funding & Business7 days ago

Rethinking Venture Capital’s Talent Pipeline

-

Jobs & Careers7 days ago

Why Agentic AI Isn’t Pure Hype (And What Skeptics Aren’t Seeing Yet)

-

Funding & Business4 days ago

Sakana AI’s TreeQuest: Deploy multi-model teams that outperform individual LLMs by 30%

-

Jobs & Careers7 days ago

Astrophel Aerospace Raises ₹6.84 Crore to Build Reusable Launch Vehicle

-

Jobs & Careers7 days ago

Telangana Launches TGDeX—India’s First State‑Led AI Public Infrastructure

-

Funding & Business1 week ago

From chatbots to collaborators: How AI agents are reshaping enterprise work

-

Jobs & Careers5 days ago

Ilya Sutskever Takes Over as CEO of Safe Superintelligence After Daniel Gross’s Exit