Education

Global ELT recovery stalls across major study destinations

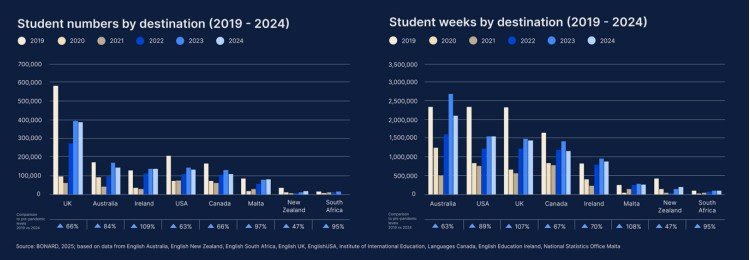

According to the third edition of BONARD Education’s Global ELT Annual Report 2025, recovery has stalled in most major destinations, with the global ELT sector in 2024 reaching 73% of 2019 student volumes and 75% of student weeks, a slower progress than in 2023.

The report highlighted that despite early optimism for 2024, stricter immigration policies in major destinations like the UK, Canada, and Australia, combined with currency depreciation and inflation, slowed the sector’s recovery.

“Between 2023 and 2024, the combined pressures resulted in a 10% decline in student weeks and a 6% decrease in student numbers across the eight major destinations,” read the BONARD report.

Ireland was the only destination to surpass pre-pandemic levels in both student numbers (109%) and student weeks (107%), while Malta exceeded 2019 student weeks despite shorter stays.

However, growth slowed in both countries in 2024, with early indicators suggesting a decline in student weeks in 2025.

“Ireland and Malta’s visa-friendly policies and work opportunities have helped them attract students discouraged by stricter regulations, high course fees and other expenses in other destinations,” stated Ivana Bartosik, international education director at BONARD.

“This welcoming approach has enabled them to remain more attractive than other ELT destinations, with Ireland even surpassing both the US and Canada in total student numbers.”

Among other destinations, the US continued to lag, reaching only about 63% recovery in student numbers, with visa denials and competition limiting growth prospects, while in Canada, study permit caps and stricter financial requirements have further driven a downward trajectory in ELT student numbers.

Visa denials have emerged as the leading challenge for the US ELT sector, with 61% of programs citing them as the top industry concern, as reported by The PIE News.

The UK remained a significant ELT market, capturing 38% of global share, driven largely by strong junior enrolments, a trend also seen in Ireland and Malta, though the country continues to face steep declines.

In 2024, ELT student mobility was increasingly shaped by two dominant factors: high visa refusal rates and affordability constraints

Sarah Verkinova, BONARD

Meanwhile, Australia, despite leading in student weeks for the third year, experienced a significant reduction in 2024, with student weeks down 22% and student numbers falling 16% amid high visa refusal rates and rising fees.

The decline comes as Australia’s ELICOS sector warns that rising visa fees are “killing” the industry, with numerous institutes shutting down in recent months, a stark contrast for a sector that once aspired to be the global ELT learners “destination of choice”.

Moreover, New Zealand posted 44% year-on-year growth but remains the slowest to recover, reaching only 47% of 2019 levels, while South Africa has achieved 95% recovery and is gaining momentum from emerging African markets, as per the report.

“In 2024, ELT student mobility was increasingly shaped by two dominant factors: high visa refusal rates and affordability constraints. In key destinations like Canada, Australia, and the UK, stricter visa policies and rising application fees created setbacks in the student journey,” noted Sarah Verkinova, head of international education at BONARD.

“Consequently, alternative destinations gained popularity, and a minimum of 100,000 students enrolled in ELT courses in Dubai and the Philippines.”

In terms of ELT source markets, Brazil surpassed Colombia to become the largest globally, despite a 14% drop in student weeks, with China recording the highest growth (+21%), though volumes remain below pre-pandemic levels.

Meanwhile, growth in Dubai and the Philippines, along with strong gains from emerging markets such as Nepal (+96%), the UAE (+107%), and Kazakhstan (+26%), highlights an ongoing diversification beyond traditional markets.

“2024 may serve as the new benchmark year for China, as further rapid growth is unlikely,” stated Kristina Benedikova, an international education consultant at BONARD.

“The increasing availability of local ELT options in countries like Malaysia and the Philippines, along with rising competition from in-country providers, is reshaping student preferences toward more cost-effective and accessible destinations.”

Education

‘I regret pushing my daughter into school until she broke’

Ben SchofieldPolitics correspondent, BBC East

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCThe start of the school year saw the Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson warn parents about the need for children to attend classes.

Data suggests half of pupils who missed lessons in the first week of term last year went on to become persistently absent.

But school leaders say they are seeing more children who find attending school too traumatic.

What is it like having a child with what psychologists call emotionally based school avoidance and what should be done to help?

Family handout

Family handoutThe final time Julie took her daughter to school in July 2023, a member of staff congratulated her.

Rosie, who was then eight, was “wearing a dirty pyjama top, a pair of jogging bottoms, a pair of trainers with no socks, she had her headphones on, she was holding a teddy”, Julie recalls.

“I walked into school and the [special needs co-ordinator] then said to me ‘well done, you got her here’.”

But for Julie, 48, it was not a “win”.

“She couldn’t even speak, she hadn’t eaten, she had maybe three or four hours sleep.

“But I’d done a good job as a parent for making her go to school?”

Family handout

Family handoutAt the time Rosie, who has autism, was in Year Three at a primary school in Northamptonshire.

Julie says her daughter had struggled with the school environment since her time in nursery and is now educated out of school.

Rosie, she recalls, was “in fight and flight the whole time” she was in the classroom, which “just overwhelmed her”.

Eventually Rosie was “begging not to leave” the house for school and was self-harming, sometimes on the school run.

“She would have night terrors – she would be up screaming, if she went to sleep at all.

“It just felt as if I was walking her into the lion’s den every single day,” she says.

Meanwhile, Julie and her husband James received letters and home visits from school staff about Rosie’s attendance.

“It was very lonely.

“All of a sudden there’s these letters and people are talking about fines and I was lost.”

On that final say Julie says she “dragged” Rosie to school because “that was the expectation”.

Now she wishes she had taken Rosie out of school earlier.

“But I also feel that if I hadn’t have got to the point… where she broke, I would never have known if it had worked,” she says.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCBased on Rosie’s reaction to school, an educational psychologist who assessed her noted she had “emotionally based school avoidance” or EBSA, a condition school leaders say they are encountering more.

Anna Hewes, the head teacher of Prince William School, a 1,400-pupil secondary in Oundle, Northamptonshire, says schools are seeing a “big increase” in EBSA among pupils in Year Seven, Eight and Nine.

The transition to secondary school is, she adds, a “key time” and at the start of the school year EBSA is “at the forefront of our minds because of the new year sevens coming through”.

The “noises, the bustling nature of a school – the busyness, all the classes walking around” make it a “real challenge” for those with sensory needs, she says.

But more generally “it’s very tough to be a teenager these days”.

Smartphones and social media, she adds, mean “young people can’t escape anymore”.

“It definitely is a post-Covid spike and these young people are genuinely really struggling to step over the threshold of the school and sometimes leave their bedrooms.”

DJ McLaren/BBC

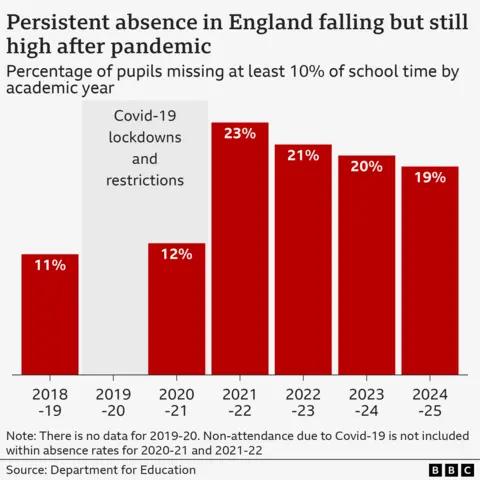

DJ McLaren/BBCAcross England, rates of “persistent absence” – when pupils miss 10% or more of lessons – have remained high since the pandemic.

Last academic year almost 19% of pupils were persistently absent, compared with 11% in 2018/19.

Mrs Hewes says EBSA is a “significant part” of the issue.

A lack of reliable data, however, means it is difficult to know how big a part.

Mrs Hewes says Prince William Academy prioritises “inclusion” and has recruited an assistant head teacher for “belonging”.

It has also opened a specialist “school-within-a-school” for pupils with EBSA, funded by North Northamptonshire Council. Four students have been enrolled so far and by 2028 it expects to see 48.

Jenny Nimmo, the head of inclusion at East Midlands Academy Trust, which runs Prince William Academy, says the unit will have more “homely” classrooms and on-site mental health provision.

She hopes it will be “future proof” because EBSA “isn’t going away”.

There are, she adds, “more and more young people” with “emotionally based school avoidance and indeed anxiety”.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCThe Compass Centre in Luton also help pupils with EBSA access education.

Dr Joanne Summers, Luton Borough Council’s principal educational psychologist, says the condition can appear suddenly but “when you look back, there has been anxiety around being in school” and one incident might be a “catalyst”.

Intervening early, she adds, is important, as falling behind on school work and losing contact with friends can make anxiety worse.

Dr Summers says Luton has been trying to move away from seeing school absences as “defiance and truancy”.

“We are being curious about what’s going on for that young person, why is it that they are behaving in this way,” she adds.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCGeoff Barton, a former head teacher in Suffolk and previous general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, says there should be more “emphasis on the humanity of our schools” rather than “draconian discipline” over absences.

He is researching special educational needs (Send) provision for the left-leaning think tank the Institute for Public Policy Research.

He says the people he is speaking to are “universally saying” that anxiety among pupils has increased.

But the “age of anxiety” is only one reason for persistent absence.

Another is poverty, while he says there is also a “long shadow in education of Covid” when “schools started to feel a bit more of an optional decision”.

Cornelia Andrecut, the executive director of children’s services for North Northamptonshire Council, said the authority has offered training courses for schools to learn strategies to support children with EBSA.

The government says it will spend £740m creating “more specialist places in mainstream schools” and placing Send leads in 1,000 new family hubs.

A Department for Education spokesperson says: “Schools should take a ‘support first’ approach for children who are facing barriers to regular school attendance, and we are expanding access to mental health support teams in all schools, ensuring that every pupil has access to early support services in their community.”

Family handout

Family handoutFor Julie, taking Rosie out of school was “not a lifestyle choice” but was prompted by “trauma and distress” that her daughter is still recovering from.

Does she regret pushing Rosie to attend school?

“Yeah – definitely.

“I always wonder if there was a bit of trust broken between us as mum and daughter when I still took her into that place when it was that bad.”

Education

Earl Richardson, who spotlighted HBCU funding disparities, dies : NPR

Earl Richardson was the president of Morgan State University between 1984 and 2010.

Morgan State University

hide caption

toggle caption

Morgan State University

Earl Richardson was a Black college president — “armed with history,” as a colleague described him — when he led a 15-year-long lawsuit that ended in a historic settlement for four Black schools in Maryland and put a spotlight on funding disparities for all of the nation’s historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

Richardson’s death, at 81, was announced on Saturday by Morgan State University, located in Baltimore, where he served as president when he helped organize the lawsuit that began in 2006. It was settled in 2021 when the state of Maryland agreed to give $577 million in supplemental funding over 10 years to four HBCUs.

Richardson led Morgan State from 1984 to 2010 and he had long chafed at stretching the little funding he got from the state. In the lawsuit, plaintiffs argued that Maryland had historically underfunded its Black colleges and had put them at a disadvantage by starting and boosting similar programs at nearby majority-white schools.

David Burton, one of the plaintiffs, told NPR that the case was compared to Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark lawsuit that brought up similar issues of disparities in educational opportunities for Black students, but the Maryland case raised the issues for students in higher education.

In 1990, when Richardson was a new school president, students took over the administration building for six days to protest the school’s dilapidated classrooms and dorms, with roofs that leaked and science labs stocked with outdated equipment.

Edwin Johnson was one of those student protesters. “We originally were protesting against Morgan’s administration,” including Richardson, he said. “But then after we dig and do a little research, we find out it’s not our administration, but it’s the governor down in Annapolis that isn’t equipping the administration with what they need to appropriately run the school.”

The protest ended when the students marched 34 miles to Annapolis to demand a meeting with the governor.

Richardson, who spoke of taking part in civil rights demonstrations when he was in school, had subtly guided the students to the correct target, said Johnson, who is now the university’s historian and special assistant to the provost.

That protest helped pave the way to the future, historic lawsuit.

Because Richardson was the university’s president, and an employee of the state, he couldn’t sue the state. So, a coalition of students and former students was created, the Coalition for Equity and Excellence in Maryland Higher Education Inc., to serve as the plaintiff.

Still, Richardson was the visionary behind the lawsuit, said Burton, a Morgan State alumnus and now a strategic planner for businesses. “He was armed with history,” Burton said.

“Dr. Richardson knew where the skeletons were,” Burton added. He was “a force that the state could not reckon with because of his institutional knowledge.”

At one point, during the trial, state attorneys objected to Richardson’s presence in the courtroom and asked the judge to make him leave, even though he had a right to be there as an expert witness, said Jon Greenbaum, then the chief counsel of the Lawyer’s Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, who helped argue the lawsuit.

Richardson stayed in the courtroom and “because this was really a desegregation case,” said Greenbaum, he provided historical detail that became critical to the arguments made by the lawyers representing the plaintiffs.

The funding that resulted, and Richardson’s leadership, jump-started what is now called on campus “Morgan’s Renaissance.” Or sometimes, said Johnson: “Richardson’s Renaissance” — because during Richardson’s presidency, enrollment doubled, the campus expanded with new buildings and new schools were added, including a school of architecture and a school of social work.

Richardson’s work put a spotlight, too, on the funding disparities faced by HBCUs across the country. They are more likely than other schools to rely upon federal, state and local funding — money that has faced budget cuts in recent years. Compared to other universities and colleges, HBCUs get a higher percentage of their revenue from tuition and less from private gifts and grants, according to one study.

In testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives in 2008, Richardson emphasized the mission of HBCUs when he told lawmakers that Black schools like his educated the most talented Black students but also sought to attract students who didn’t consider, or thought they couldn’t afford, to go to college. “We can make them the scientists and the engineers and the teachers and the professors — all of those things,” he said. But only if “we can have our institutions develop to a level of comparability and parity so that we are as competitive as other institutions.”

Education

How millions of dollars in funding cuts will impact Hispanic Serving Institutions

Chancellor Sonya Christian of the California Community College system talks about the impact of funding cuts for students.

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms1 month ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Funding & Business3 months ago

Funding & Business3 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries