Education

Cisco Introduces AI-First Approach to IT Operations — Campus Technology

Cisco Introduces AI-First Approach to IT Operations

At its recent Cisco Live 2025 event, Cisco announced AgenticOps, a transformative approach to IT operations that integrates advanced AI capabilities to enhance efficiency and collaboration across network, security, and application domains. Central to this paradigm are the Cisco AI Assistant, Cisco AI Canvas, and the Deep Network Model, each playing a role in redefining modern IT workflows.

AgenticOps: A New Paradigm for IT Operations

AgenticOps represents Cisco’s vision for an AI-driven operational model where intelligent agents autonomously manage and optimize IT tasks. This approach leverages real-time telemetry, automation, and deep domain expertise to deliver intelligent, end-to-end actions at machine speed, all while keeping IT teams in control, Cisco said.

Key components of AgenticOps include:

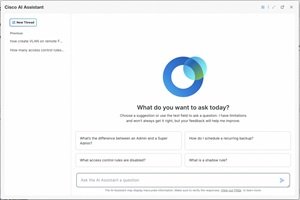

- Cisco AI Assistant: A conversational interface that identifies issues, diagnoses root causes, and automates complex workflows.

- Cisco AI Canvas: A shared, interactive workspace featuring a generative UI that unifies data across networking, security, and observability domains.

- Deep Network Model: A domain-specific large language model (LLM), a specialized LLM trained on Cisco’s networking knowledge, including CiscoU and CCIE materials, built on over 40 years of Cisco expertise.

Cisco AI Assistant: Conversational Control Across the Ecosystem

The Cisco AI Assistant serves as the foundational layer of AgenticOps, providing a natural language interface that allows IT professionals to interact with their systems more intuitively. By leveraging the Deep Network Model, the AI Assistant can:

- Quickly identify critical issues and diagnose root causes.

- Assist with network configurations and policy management.

- Automate routine tasks, such as NAC configurations or switch migrations, reducing task time from hours to minutes.

- Provide actionable insights and recommendations, enhancing decision-making processes.

By integrating deeply into Cisco’s platform, the AI Assistant ensures that IT teams can easily incorporate its capabilities into their existing workflows, streamlining operations and improving efficiency.

Cisco AI Canvas: A Collaborative Workspace for Cross-Domain IT

Building upon the AI Assistant, the Cisco AI Canvas introduces a generative user interface designed to facilitate real-time collaboration among NetOps, SecOps, and application teams. Key features of the AI Canvas include:

- Integration of real-time telemetry from sources like Meraki, ThousandEyes, and Splunk, providing a unified view of the IT environment.

- Dynamic generation of dashboards and visualizations tailored to specific incidents or workflows.

- Advanced reasoning models that break down troubleshooting into structured steps, guiding teams through diagnostics and remediation.

- Collaborative features that allow team members to share dashboards, invite collaborators, and persist sessions across time.

- Execution capabilities that enable the AI Canvas to implement configuration changes or execute runbook steps upon team agreement.

By centralizing data and collaboration tools, the AI Canvas empowers IT teams to resolve issues more efficiently and with greater transparency.

Education

Gun violence data puts recent high-profile shootings in context : NPR

Crime scene tape blows in the wind as rain begins to fall outside Evergreen High School in Colorado on Sept. 11.

RJ Sangosti/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

RJ Sangosti/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images

On a visceral level, it feels far too common.

A week ago, conservative activist Charlie Kirk was assassinated while speaking at a college in Utah. That same day, a student opened fire at a Colorado high school, critically wounding two peers. Just two weeks earlier, a mass shooting at a Minnesota Catholic church killed two children and injured 21 others.

Once again, a series of horrific, high-profile shootings has gripped the country and brought national focus to the issue of gun violence, especially as it relates to school safety and politically motivated attacks.

NPR spoke with experts on mass shootings, political violence, and school attacks about the data, trends and context to better understand this moment.

Here’s what to know.

Are mass shootings becoming more frequent?

There’s no universal definition for a mass shooting, so data can vary based on the number of victims killed or injured, where the shooting took place, and whether it was related to gang activity or terrorism.

For example, the Regional Gun Violence Research Consortium at the Rockefeller Institute of Government, a nonpartisan think tank, only tracks shootings that occur in public or populated places, involve at least two victims (injured or killed), and excludes incidents related to gang violence or terrorist activity. By their definition, there have been 12 mass shootings in 2025.

Meanwhile, the Gun Violence Archive — which counts all instances in which four or more people were shot (injuries and deaths), not including the shooter, and regardless of location — reported over 300 mass shootings this year.

Still, by most standards, mass shootings are more frequent now than they were 50 years ago, according to Garen Wintemute, director of the Centers for Violence Prevention at the University of California, Davis. At the same time, mass shooting deaths represent only a tiny fraction of people killed by gun violence. Wintemute said that most also don’t resemble the attacks that dominate national headlines.

“ Most mass shootings are not events that generate a lot of publicity,” he said. “ Most mass shootings have some connection to domestic violence.”

Everytown for Gun Safety, an advocacy group that uses data from the Gun Violence Archive, found that in 46% of mass shootings from 2015 through 2022, “the perpetrator shot a current or former intimate partner or family member.”

What about school shootings?

Gun-related incidents on school grounds have surged since the pandemic, according to David Riedman, a researcher who tracks all cases in which a gun is fired, brandished or in which a bullet hits K-12 school property. His K-12 School Shooting Database shows that there have been more than 160 incidents so far this year.

Before 2021, the number of instances had not surpassed 124. But by 2023, that figure climbed to 351. While the recent attack at Evergreen High School in Colorado is front of mind, Riedman said most shootings are the result of an escalated dispute.

“ That really escalated in the late 2010s and then became an even bigger problem post-COVID during the return of both students and community members to the campuses,” he said.

At large, only a small share of K-12 schools report gun-related instances each year, according to Riedman. Among school incidents, part of the issue is that some students live in homes where firearms are easily accessible or not properly secured, he said.

“There are students arrested with guns at schools just about every single day, and they don’t have a plan to shoot anyone,” Riedman said. “They just carry the gun with them often for either the prestige of having it or for protection because they themselves fear being victimized.”

Are politically motivated attacks becoming a bigger threat in the U.S.?

Political violence has been rising over the past decade, according to terrorism and gun violence experts. Joshua Horwitz, the co-director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions, said while the issue has existed throughout American history, the recent surge is significant.

“Just in the last 12 months we’ve seen terrible, terrible examples of political violence,” he said. “ We’ve just seen a lot more intimidation lately.”

There are a few ways to measure this, but one indicator comes from the U.S. Capitol Police. In 2024, the agency investigated over 9,400 “concerning statements and direct threats” against members of Congress — more than twice the number in 2017.

In a study published on Monday, Wintemute of UC Davis found that while most Americans reject political violence, those who hold harmful beliefs — such as racism, hostile sexism, homonegativity, transphobia, xenophobia, antisemitism, or Islamophobia — are also more likely than others to believe that political violence is justifiable. Support for political violence was even higher among individuals who harbored multiple hateful phobias, according to his survey of over 9,300 adults.

But Wintemute’s research also suggests there are small steps that can help curb political violence. In a survey conducted last year, a small number of respondents said they would participate if a civil war broke out. Yet, of that group, about 45% said they would abandon that position if urged by family members.

“ We just need to make sure that those of us who reject it speak as loudly as do those who support it,” he added.

How widespread is the issue of gun violence?

More than 46,000 people died from gun-related injuries in 2023, according to an analysis by Pew Research Center using the latest available data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Gun homicides have declined since 2021, while suicides continue to make up a majority of gun deaths, Pew Research found. But for many Americans, gun violence may hit closer to home than many people expect.

In 2023, Liz Hamel and her team at KFF, a health research group, conducted a survey of more than 1,200 adults across the country about their experiences with gun-related incidents. The survey found that 1 in 5 respondents said they have personally been threatened with a gun, while nearly 1 in 6 said they have personally witnessed a person get shot. Worries about gun violence also affected Black and Hispanic respondents disproportionately.

“We often see national attention to the issue of gun violence in the wake of high-profile events,” Hamel said. “What our polling really shows is that experiences with gun-related incidents are more common than you might think among the U.S. population.”

In the survey, 84% of all participants said they have taken at least one precaution to protect themselves against gun violence. The most common step was speaking to loved ones about gun safety. But about a third said they have avoided large crowds or big events. Meanwhile, 3 out of 10 said they have purchased a firearm to protect themselves or their family from gun violence.

Of the people who have a gun in their home, nearly half of participants said a firearm was stored in an unlocked location and more than one-third said a gun was stored loaded. More than half said at least one gun is stored in the same location as the ammunition. Those results suggest the need for more efforts to teach the public about safe gun storage practices, according to Hamel.

“ We do see opportunities for improved awareness around gun safety,” she said.

Education

I toured UK council estates and learned this: all our lives are poems just waiting to be written | Rowan McCabe

When I first suggested knocking on strangers’ doors and offering to write a poem for them, for nothing, on any subject of their choosing, the responses weren’t exactly enthusiastic. I’m from Heaton in Newcastle upon Tyne, where the project began. One day, I happened to mention it to a taxi driver as I travelled through Byker, near Newcastle city centre. “It would never work round here,” he said, pointing out of the window.

The building he was pointing to was the Byker Wall, an estate near where I live – I’ll admit it’s not the first place you’d visit on the hunt for a bard. When I told my friends and colleagues that I was planning to try Door-to-Door Poetry here, they all made exactly the same sound – a Marge Simpson-esque expression of unease. I mentioned it to a trainee police officer who lived close to me. “Take some pepper spray and don’t carry any valuables,” she advised soberly. Having grown up on a council estate myself, I wasn’t as apprehensive as I might have been. But warnings like this still did a lot to rattle my nerves.

When I arrived at the Byker Wall, the first person to answer was a man called Carl. He had bright blue eyes, a peaked baseball cap, and was wearing a Newcastle shirt. I performed an introductory poem for him while he stared back at me, completely expressionless. When I got to the end, I explained I could write him a poem about anything he wanted.

“So what is important to you?” I asked. “Getting wrecked,” Carl replied. I could tell from the off that this was a “testing the boundaries” thing. I told Carl I would be more than happy to write a poem for him about getting wrecked. Whatever was important to him, really.

Something in his face changed. “Will you write me one about how much I love my girlfriend?” he said. The conversation had gone from hardcore to sentimental in about three seconds.

I wrote a poem for Carl about his and his partner’s first date. He told me he really enjoyed it. He was one of seven people who asked for a poem in the Byker Wall estate. And it was this hugely positive experience that set me off on a journey, one that would introduce me to a great many more residents in social housing and council estates across the land.

In Boston, Lincolnshire, which has been dubbed England’s “most divided” town, I met five people on a street called Taverner Road. One of them was a woman named Pauline, who asked for a poem about “banger racing”, a sport that involves souping up secondhand cars and then crashing them into each other at great speed. I didn’t know anything about banger racing until that point, so the next day I went to watch some at Skegness Raceway before writing Pauline’s poem.

On an estate in Moss Side, Manchester, I met a man who asked to be referred to as “the specialist”. I showed him my introductory poem and he shook my hand. “You’ve come to the right place,” he said. He told me what I was doing was freestyle, in the true sense of the word, before explaining that I resembled an 18th-century time traveller. I wrote him a poem about that.

I visited estates across the country, and the response was always the same. Whether people were existing fans of poetry or not, so many of them stopped to listen, to chat about their lives and to gratefully receive the resulting poem.

Towards the end of my adventures, in Jaywick, Essex – often described as the “most deprived town” in England – I met Sarah, a woman with red hair and tattoos on her arms. She lamented the fact that the media only seemed to visit Jaywick to write a terrible story about it, and asked for a poem about its best side instead. This request led me to discover the beautiful beaches, as well as a fantastic fish and chip shop called Ozzy’s.

The whole experience got me thinking about why we write poetry and who it is really for. In a world in which poetry is still seen by many as opaque and inaccessible, we discuss innovative ways to engage people with it. But it seems to me that another, more important issue is who we imagine will read the poem when it is finished. And how we want them to feel once they have.

Trying my Door-to-Door Poetry on a range of estates forced me to question some of my own preconceptions. It invited me to consider the fact that, in any given place, there is always a wide variety of people; that when we take the time to get to know someone, especially someone who lives their life differently to us, we are often embarking on a journey of self-discovery too. In a world that can feel increasingly divided and polarised, I am grateful to have had the chance to learn this – from house to house, poem to poem and door to door.

On Visiting Jaywick

Yes, Jaywick, I’ll confess my reservations.

Your name I’d heard, your headlines I had read.

I took the bus, explained my destination,

The driver fixed me with a look of dread.

But on that evening, walking on your beach,

The sky was clear, the sun bobbed on the waves,

The soft and golden sand was at my feet,

Dog walkers smiled and went about their day.

And honestly? It took me by surprise,

Your natural beauty shook away my blues,

I couldn’t help but pause and wonder why

This scene had never featured on the news.

For certain as each summer fades to brown,

The tabloids yearly come here for a snap

Of what they’ve dubbed a run-down, worthless town

(Though who’s in charge of it, they never ask).

They hunt for weeds and windows that need fixed,

They hover round like poachers in the road,

But do they stay for views as grand as this

Before they pen their articles of woe?

Because I know you have your problems, Jaywick.

But people here are welcoming and kind.

And Ozzy’s does the perfect fish and chips,

Next to a pub that’s called Never Say Die.

But that won’t make the front page, nor the sea

As it glitters here above your coastal shelf,

When papers only deal in misery,

I’m pleased I found the truth out for myself.

Education

What I Learned After Building a Tech Tool to Support Student Well-Being

This story was published by a Voices of Change fellow. Learn more about the fellowship here.

One morning, my computer science students opened their laptops for our daily mental health check-in. One of my seventh graders, usually the first to speak, sat quietly. As she submitted her daily check-in, she chose the tired emoji and typed, “Stayed up all night at the hospital with my mom.” I planned a different lesson for that day, but after reading that sentence in her check-in, I adjusted her task so she could move at her own pace. After class, I met with her in private to offer additional support, and with her permission, we told her teachers that she might need flexibility that day.

In the meantime, I also sent a private note to the Student Emergency Support Team through our online teacher check-in tool. During the school day, our Student Emergency Support Team responds on-site to mental health concerns. If needed, a team member comes to the room, helps the student step into a calm space and coordinates care with the counselor and family. The team records a brief status in our secure system and sends a follow-up plan to the teacher. The Student Emergency Support Team comprises an administrator, the school counselor and a restorative practices lead. After hours, the same team monitors mental health alerts on a rotating schedule and reaches families when urgent support is needed.

In 2018, when I began teaching at Guilford Preparatory Academy, moments like this were easy to miss. I often learned about a student’s struggle only after grades fell or behavior shifted. I cared, but I did not have a consistent way of hearing about student mental health issues until a student informed me, much like my computer science student. During the pandemic, distance and camera-off days made it even harder to see who needed care.

I knew we needed change. That’s when I decided to implement a simple system that could change our school and protect student mental health.

Soon, technology became an essential tool for our students, teachers and administrators, forever changing how we support learner well-being and mental health.

The Time Before Technology

Before 2018, there was no consistent system at our school for identifying or supporting students who were struggling with mental health. Much of what we learned came only after visible changes in behavior or academic performance. A student might suddenly stop turning in assignments, begin acting out in class or withdraw from friends and only then would a teacher begin to ask questions. This approach often meant that by the time we noticed, the student had already been carrying the weight of their struggles for weeks or even months.

My fellow teachers and I did the best we could with what we had. We leaned heavily on hallway conversations, parent phone calls and observations, but these were reactive instead of proactive. If a student broke down in class, we comforted them in the moment, but once they left our room, the support often stopped unless someone followed up. Teachers cared deeply, but there was no formal structure that allowed us to work together in real time.

The impact on students was significant. Many did not feel comfortable speaking up about their needs, and those who did often had to repeat their stories to several adults before receiving help. This led to frustration and, in some cases, further withdrawal. It was challenging and discouraging for teachers to know a student was struggling but not have the tools to respond quickly or consistently.

Looking back, I see that our care was genuine, but without technology, it lacked the coordination our students deserved. It was then that I started using a tool called Care Check, which, at its core, is a digital check-in tool for students. The check-in involves students logging in, selecting an emoji that matches how they are feeling and writing one sentence.

Not only did it become an essential part of the school day for students, but it also became the basis of a new system of monitoring, care, and supporting student and learner well-being.

Technology That Cares

When campuses closed in spring 2020, they served as both attendance and mental health support. Even on “camera-off” days, students could choose an emoji and write one honest line. After returning to in-person classes, these small entries helped teachers identify emotional patterns and intervene quickly to support students.

For example, in my classroom, one student shared that a noisy home environment made homework very difficult. I adjusted expectations and offered him different ways to demonstrate his learning, which helped him succeed on his own terms. Another student used our digital check-in tool to share quiet reflections that she might not have spoken aloud. Those reflections opened the door to new friendships in our after-school program. These digital routines give students safe and supportive ways to communicate their emotional needs without having to raise their hands or speak in front of the class.

Technology also helped us bring families into the process. I knew my students’ families had limited capacity, so we utilized a parent communication platform called ClassDojo to update families in real time. Messages are brief, translated into home languages and focused on what matters: the health and well-being of the student. This builds trust and ensures that care continues at home. Families no longer have to wait for a call or hope for a meeting. They know their child’s emotional health is being tracked and supported during the school day.

Teachers also benefit from digital systems. Through our staff dashboard, they receive only the most essential updates, like “needs flexibility today” or “check-in recommended.” This avoids overwhelming them with unnecessary detail. Instead of carrying the emotional weight alone, teachers can collaborate and share responsibility with the larger team. Technology makes this kind of coordination possible. It keeps care organized, respectful and sustainable for everyone involved.

Technology That Connects

This work began in 2018 in response to a gap I saw in my classroom. Since then, technology has become the foundation of our care model at Guilford Preparatory Academy.

What we have built is more than a digital toolkit. It is a consistent and school-wide structure for emotional care. Students feel safe naming their emotions. Families know that support is active and ongoing. Teachers have the appropriate systems in place to respond without becoming overwhelmed. These results are possible because technology creates the structure that holds everything together.

Technology does not replace human connection. If anything, it strengthened our school community and allowed us to center the people who matter most.

-

Business3 weeks ago

Business3 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms1 month ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers3 months ago

Jobs & Careers3 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Funding & Business3 months ago

Funding & Business3 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries