- The FTC is investigating how companies use personal and behavioral data to set individualized prices.

- Critics say surveillance pricing threatens consumer welfare and may cross constitutional lines.

- A lack of robust data privacy protections is at the heart of the issue, according to experts

AI Insights

China’s Open-Source Models Are Testing US AI Dominance

While the AI boom seemingly began in Silicon Valley with OpenAI’s ChatGPT three years ago, 2025 has been proof that China is highly competitive in the artificial intelligence field — if not the frontrunner. The Eastern superpower is building its own open-source AI programs that have demonstrated high performance as they put ubiquity and effectiveness over profitability (while still managing to make quite a bit of money), the Wall Street Journal reports.

DeepSeek is probably the most well-known Chinese AI entity in the U.S., whose R1 reasoning model became popular at the start of the year. Being open-source, as opposed to proprietary, means these programs are free and their source code can be downloaded, used and tinkered with by anyone. Qwen, Moonshot, Z.ai and MiniMax are other such programs.

This is in contrast to U.S. offerings like ChatGPT, which, though free to use (up to a certain level of compute), are not made available to be modified or extracted by users. (OpenAI did debut its first open-source model, GPT-OSS, last month.)

American companies like OpenAI are racing to catch up — monopolies and industry-standard technologies are often the ones that are the most accessible and customizable. The Trump administration wagered that open-source models “could become global standards in some areas of business and in academic research” in July.

Want to join the conversation on how the security of information and data is impacting our global power struggle with China? Attend the 2025 Intel Summit on Oct. 2, from Potomac Officers Club. This GovCon-focused event will include a must-attend panel discussion called “Guarding Innovation: Safeguarding Research and IP in the Era of Strategic Competition With China.” Register today!

China’s Tech Progress Has Big Implications

The Intel Summit panel will feature, among other distinguished guests, David Shedd, a highly experienced intel community official who was acting director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (after serving as its deputy director for four years) and deputy director of national intelligence for policy, plans and procedures.

Shedd spoke to GovCon Wire in an exclusive interview about China-U.S. competition ahead of his appearance on the panel. He said that China’s progress in areas like AI should not be taken lightly and could portend greater problems and tension in the future.

“Sensitive IP or technological breakthroughs in things like AI, stealth fighter jets, or chemical formulas lost to an adversary do not happen in a vacuum. They lead, instead, to the very direct and very serious loss of the relative capabilities that define and underpin the balance and symbiosis of relationships within the international system,” Shedd commented.

Open-source models are attractive to organizations, WSJ said, because they can customize the programs and use them internally and protect sensitive data. In their Intel Summit panel session, Shedd and his counterparts will explore how the U.S. might embrace open-source more firmly as a way to stay agile in the realm of research and IP protection.

Who Is Stronger, America or China?

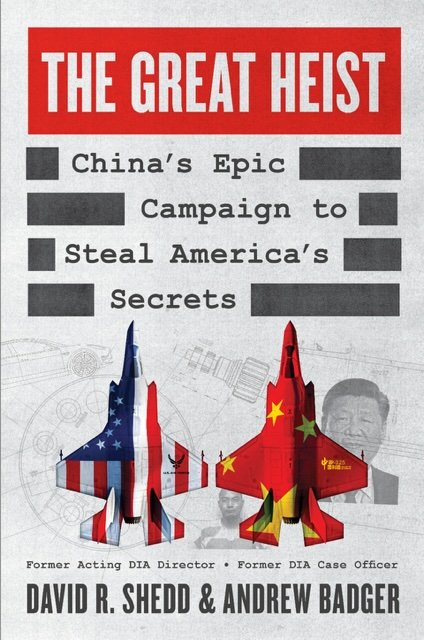

Shedd, along with co-author Andrew Badger, is publishing a book on December 2 entitled “The Great Heist: China’s Epic Campaign to Steal America’s Secrets.” Published through HarperCollins, the volume will focus on the campaign of intellectual property theft the Chinese government is waging against the U.S.

Shedd elaborated for us:

“The PRC/CCP’s unrelenting pursuit of stolen information from the West and the U.S. in particular has propelled China’s economic and military might to heights previously unimaginable. Yet we collectively continue to underestimate the scale of this threat. It’s time for the world to fully comprehend the depth and breadth of China’s predatory behavior.

Our national security depends on how we respond—and whether we finally wake up to the reality that China has already declared an economic war on the West using espionage at the forefront of its campaign. It already has a decades-long head start.”

Don’t miss former DIA Acting Director David Shedd, as well as current IC leaders like Deputy Director of National Intelligence Aaron Lukas and CIA’s AI office Deputy Director Israel Soong at the 2025 Intel Summit on Oct. 2! Save your spot before it’s too late.

AI Insights

What is surveillance pricing? – Deseret News

They know who you are, where you live, how much money you make and where you spent your last vacation.

They’re watching what websites you visit, tracking your mouse movements while you’re there and what you’ve left behind in virtual shopping carts. Mac or PC? iPhone or Android? Your preferences have been gathered and logged.

And they’ve got the toolkit, powered by artificial intelligence software, to assemble all this information to zero in on exactly how much you’re likely willing to pay for any product or service that might strike your fancy.

The “they” is a combination of retailers and service providers, social media operators, app developers, big data brokers and a host of other entities with whom you have voluntarily and involuntarily shared personal and behavioral information. And they’ve even come up with new labels to make you feel better about the systems that are using your personal data to set a custom price.

Dynamic pricing. Personalized pricing. Even “discount pricing.”

FTC investigates surveillance pricing

But the Federal Trade Commission and others have another name for it: surveillance pricing.

In an ongoing investigation launched last year, the FTC is looking into the practice of surveillance pricing, a term for systems that use personal consumer data to set individualized prices — meaning two people may be quoted different prices for the same product or service, based on what a company predicts they are willing — or able — to pay.

Part of the FTC’s mandate includes working to prevent fraudulent, deceptive and unfair business practices along with providing information to help consumers identify and avoid scams and fraud, according to the agency.

In a preliminary report in January, the agency highlighted actions it’s already taken to quell the rise of surveillance pricing amid its effort to gather more in-depth information on the practice:

- One complaint issued by the FTC included allegations that a mobile data broker was harvesting consumer information and sensitive location data, including visits to health clinics and places of worship which was later sold to third-parties.

- The agency said it issued the first-ever ban on the use and sale of sensitive location data by a data broker which allegedly sold consumer location data it collected from third-party apps and by purchasing location data from other data brokers and aggregators.

- Another FTC complaint alleged that the data broker InMarket used consumers’ location data to sort them into particularized audience segments — such as “parents of preschoolers,” “Christian church goers,” “wealthy and not healthy” — which it then provided to advertisers.

Last year, the FTC issued orders to eight companies that offer surveillance pricing products and services that incorporate data about consumers’ characteristics and behavior. The orders, according to the agency, seek information about the potential impact these practices have on privacy, competition and consumer protection.

“Firms that harvest Americans’ personal data can put people’s privacy at risk. Now firms could be exploiting this vast trove of personal information to charge people higher prices,” said then-FTC Chair Lina M. Khan. “Americans deserve to know whether businesses are using detailed consumer data to deploy surveillance pricing, and the FTC’s inquiry will shed light on this shadowy ecosystem of pricing middlemen.”

AI-driven consumer profiling

George Slover, general counsel and senior counsel for competition policy at the Center for Democracy and Technology, has his own term for the practice of using personal information to construct prices for individuals: “bespoke pricing.” He said it poses a fundamental threat to consumer welfare and free market principles.

Proponents of individualized pricing systems have argued that the method can send prices both directions — higher prices for some, lower prices for others. But Slover warned that, unlike uniform pricing, bespoke pricing enabled by “big data” and artificial intelligence gives companies little incentive to offer discounts to those who can’t afford market prices.

“Theoretically, maybe,” Slover told the Deseret News. “But as a practical matter what the sellers will do is maximize their prices. There’s a lot less incentive to lower the price for someone than raise the price for someone.”

Slover characterized the FTC investigation as “very useful” and said it could reveal more about the methodologies behind bespoke pricing and potentially lead to appropriate restrictions under existing law.

For now, he said, consumers have few defenses beyond masking their data.

“Potential ways for consumers to change their profile include working through a (virtual private network) internet connection, using an anonymized intermediary or even setting up a bogus, fictional profile … looking to reduce how much they have to pay,” Slover said.

But he cautioned that vast troves of consumer data on virtually every internet user have already been harvested and repackaged by brokers.

Slover, who has worked on antitrust and competition law for more than 35 years including stints with the U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. House of Representative’s Judiciary Committee, tied the debate over surveillance pricing to the broader need for comprehensive privacy protections.

“My organization, the Center for Democracy and Technology, was founded 30 years ago when the internet was getting off the ground,” he said. “One of the issues we’ve been focusing on since the beginning is the privacy of data … and getting Congress to implement a strong, comprehensive privacy law.”

Looking to protect data privacy

Utah state Rep. Tyler Clancy, R-Provo, said he’s not willing to wait for Congressional action on data privacy, which he sees as the critical underlying issue behind surveillance pricing.

“The privacy aspect is the biggest issue for me,” Clancy told the Deseret News. “Companies use that data to do business … but this is an area where we need some guardrails.

“If you’re creating a price for someone from immutable characteristics — race, faith, gender, ethnicity — that runs into constitutional concerns.”

Clancy said he is exploring “consent provisions” to ensure Utahns can know if their data is being used in pricing systems. He cited the response to recent news stories generated after a Delta Air Lines executive indicated in an earnings call that the carrier was testing out artificial intelligence technology that could set fares based on “the amount people are willing to pay for the premium products related to the base fares.” Delta issued a follow-up statement, clarifying that it was not using any manner of “individualized pricing” to set air fares based on customer data.

“There is no fare product Delta has ever used, is testing or plans to use that targets customers with individualized prices based on personal data,” said Delta chief external affairs officer Peter Carter.

But that qualification came after an uproar had already begun, Clancy said, and the issue has drawn interest from across the political spectrum.

“When this news story originally broke, it was a shock to people on the political right and the political left,” Clancy said.

Clancy said he’s working on a proposal for the 2026 session of the Utah Legislature and aims to compel transparency in how business entities use personal information in pricing systems for products and services.

“Sunshine is the best disinfectant and overall that’s the goal I’m trying to achieve here,” Clancy said. “It will lead to a better and freer market and that’s a win for everyone.”

Targeted advertising came first

When it comes to names, BYU marketing professor John Howell isn’t a fan of surveillance pricing, a term he believes is unnecessarily inflammatory. But he says the growing controversy over the practice isn’t about whether it’s possible or not, but whether consumers will tolerate it.

“This isn’t a new phenomenon,” Howell said in a Deseret News interview. “We’ve been paying attention to this at least from the early 2000s, individual level pricing, first-degree price discrimination. Charge every person a specific price based on their willingness to pay.”

Howell said economists have long predicted the advent of such models, but noted industry made a first stop in the advertising realm.

“It’s been conjectured as coming for at least 20 years,” he said. “Industry went to targeted advertising before targeted pricing. And I’m surprised that they went for that when targeted pricing is more profitable.”

Even if the practice is logical from a business perspective, Howell said consumer reaction is also predictably negative.

“Any time customers start to see price discounts, or individual pricing, they absolutely hate it,” he said.

And that tension isn’t new either. Howell highlighted that the Sherman Antitrust Act, passed in 1890, was “largely inspired by price discrimination by the railroad industry back at the turn of the 20th century.”

From an academic perspective, Howell said, price discrimination should benefit more consumers than it harms.

“The theory is, price discrimination almost always leads to lower average prices,” Howell said. “That doesn’t mean that every person is going to pay less. Also, it generally increases the availability of goods and services to lower-income customers.

“If you have price discrimination you can charge the people that can afford to pay a lot and less for those who cannot afford it. That’s generally what happens.”

In practice, however, Howell notes entities with the most data, and by default the most control over individual pricing systems, can easily disrupt the realm of competition.

“It’s not the theory of price discrimination that’s been disrupted,” he said. “What the data has done in our current economic system is tend to reward big players with increased power and lock out all the smaller players. As soon as they’re not competitive, the theory falls apart. If I was a policy maker, that’s what I would target, keeping big tech from accumulating so much power.”

AI Insights

Politicians hoping AI can fix Australia’s housing crisis are risking another Robodebt | Ehsan Nabavi

“This is a gamechanger”.

That’s how Paul Scully, New South Wales minister for planning and public spaces, described the state government’s launch of a tender for an artificial intelligence (AI) solution to the housing crisis earlier this month.

The system, which is aimed at cutting red tape and getting more homes built fast, is expected to be functioning by the end of 2025.

It is “allowing construction to get under way and new keys into new doors,” Scully added.

The announcement was later endorsed by the federal treasurer, Jim Chalmers, as a model for other states and territories to replicate, to “unlock more housing” and “boost productivity across the economy”.

Speeding up building approvals is a key concern of the so-called abundance agenda for boosting economic growth.

Those wheels are already in motion elsewhere in Australia. Tasmania is developing an AI policy, and South Australia is trialling a small-scale pilot for specific dwelling applications to allow users to submit digital architectural drawings to be automatically assessed against prescribed criteria.

But will AI really be a quick fix to Australia’s housing crisis?

Cutting red tape

Housing and AI were both key themes at last month’s productivity roundtable.

In a joint media release, the federal minister for housing, Clare O’Neil, and minister for the environment and water, Murray Watt, said easing “the regulatory burden for builders” is what Australia needs.

They point to the backlog of 26,000 homes currently stuck in assessment under environmental protection laws as a clear choke point. And AI is going to be used to “simplify and speed up assessments and approvals”.

None of this, however, explains AI’s precise role within the complex machinery of the planning system, leaving much to speculation.

Will the role of AI be limited to checking applications for completeness and classifying and validating documents, as Victorian councils are already exploring? Or drafting written elements of assessments, as is already the case in the Australian Capital Territory?

Or will it go further? Will AI agents, for example, have some autonomy in parts of the assessment process? If so, where exactly will this be? How will it be integrated into existing infrastructure? And most importantly, to what extent will expert judgment be displaced?

A tempting quick fix

Presenting AI as a quick fix for Australia’s housing shortage might be tempting. But it risks distracting from deeper systemic issues such as labour market bottlenecks, financial and tax incentives, and shrinking social and affordable housing.

The technology is also quietly reshaping the planning system – and the role of planners within it – with serious consequences.

Planning is not just paperwork waiting to be automated. It is judgment exercised in site visits, in listening to stakeholders, and in weighing local context against the broader one.

Stripping that away can make both the system and the people brittle, displacing planners’ expertise and blurring responsibility when things go wrong. And when errors involving AI happen, it can be very hard to trace them, with research showing explainability has been the technology’s achilles heel.

The NSW government suggests putting a human in charge of the final decision is enough to solve these concerns.

But the machine doesn’t just sit quietly in the corner waiting for the approve button to be pressed. It nudges. It frames. It shapes what gets seen and what gets ignored in different stages of assessment, often in ways that aren’t obvious at all.

For example, highlighting some ecological risks over others can simply tilt an assessor’s briefing, even when local communities might have entirely different concerns. Or when AI ranks one assessment pathway as the “best fit” based on patterns buried in its training data, the assessor may simply drift toward that option, not realising the scope and direction of their choices have already been narrowed.

Lessons from Robodebt

Centrelink’s online compliance intervention program – more commonly known as Robodebt – carries some important lessons here. Sold as a way to make debt recovery more “efficient”, it soon collapsed into a $4.7bn fiasco.

In that case, an automated spreadsheet – not even AI – harmed thousands of people, triggered a hefty class action and shattered public trust in the government.

If governments now see AI as a tool to reform planning and assessments, they shouldn’t rush in headlong.

The fear of missing out may be real. But the wiser move is to pause and ask first: what problem are we actually trying to solve with AI, and does everyone even agree it’s the real problem?

Only then comes the harder question of how to do it responsibly, without stumbling into the same avoidable consequences as Robodebt.

Responsible innovation offers a roadmap forward

Responsible innovation means anticipating risks and unintended consequences early on – by including and deliberating with those who will use and be affected by the system, proactively looking for the blind spots, and being responsive to the impacts.

There are abundant research case studies, tools and frameworks in the field of responsible innovation that can guide the design, development and deployment of AI systems in planning. But the key is to engage with root causes and unintended consequences, and to question the underlying assumptions about the vision and purpose of the AI system.

We can’t afford to ignore the basics of responsible innovation. Otherwise, this so-called “gamechanger” to the housing crisis might find itself sitting alongside Robodebt as yet another cautionary tale of how innovations sold as efficiency gains can so go wrong.

Ehsan Nabavi is a senior lecturer in Technology and Society, Responsible Innovation Lab, Australian National University. This article was first published on The Conversation

The author would like to acknowledge the contribution of Negar Yazdi, an urban planner and member of ANU’s Responsible Innovation Lab and Planning Institute of Australia, to this article

AI Insights

China Court Artificial Intelligence Cases Shape IP & Rights

On September 10, 2025, the Beijing Internet Court released eight Typical Cases Involving Artificial Intelligence (涉人工智能典型案例) “to better serve and safeguard the healthy and orderly development of the artificial intelligence industry.” Typical cases in China serve as educational examples, unify legal interpretation, and guide lower courts and the general public. While not legally binding precedents like those in common law systems, these cases provide authoritative guidance in a civil law system where codified statutes are the primary source of law. Note though that these cases are from the Beijing Internet Court and unless designated as Typical by Supreme People’s Court (SPC), as in cases #2 and #8 below, may have limited authority. Nonetheless, the cases provide early insight into Chinese legal thinking on AI and may be “more equal than others” coming from a court in China’s capital.

The following can be derived from the cases:

- AI-generated works can be protected by copyright and the author is the person entering the prompts into the AI.

- Designated Typical by the SPC: Personality rights extend to AI-generated voices that possess sufficient identifiability based on tone, intonation, and pronunciation style that would allow the general public to associate the voice with the specific person.

- Designated Typical by the SPC: Personality rights extend to people’s virtual images and unauthorized creation or use of a person’s AI-generated virtual image constitutes personality rights infringement.

- Network platforms using algorithms to detect AI-generated content for removal must provide reasonable explanations for their algorithmic decisions, particularly for content where providing creation evidence is unreasonable.

- Virtual digital persons or avatars demonstrating unique aesthetic choices in design elements constitute artistic works protected by copyright law.

As explained by the Beijing Internet Court:

Case I: Li v. Liu: Infringement of the Right of Authorship and the Right of Network Dissemination

—Determination of the Legal Attributes and Ownership of AI-Generated Images

[Basic Facts]

On February 24, 2023, plaintiff Li XX used the generative AI model Stable Diffusion to create a photographic close-up of a young girl at dusk. By selecting the model, inputting prompt words and reverse prompt words, and setting generation parameters, the model generated an image. The image was then published on the Xiaohongshu platform on February 26, 2023. On March 2, 2023, defendant Liu XX published an article on his registered Baijiahao account, using the image in question as an illustration. The image removed the plaintiff’s signature watermark and failed to provide any specific source information. Consequently, plaintiff Li filed a lawsuit, requesting an apology and compensation for economic losses. An in-court inspection revealed that, when using the generative AI model Stable Diffusion, the model generated different images by changing individual prompt words or parameters.

[Judgment]

The court held that, judging by the appearance of the images in question, they are no different from ordinary photographs and paintings, clearly belonging to the realm of art and possessing a certain form of expression. The images in question were generated by the plaintiff using generative artificial intelligence technology. From the moment the plaintiff conceived the images in question to their final selection, the plaintiff exerted considerable intellectual effort, thus satisfying the requirement of “intellectual achievement.” The images in question themselves exhibit discernible differences from prior works, reflecting the plaintiff’s selection and arrangement. The process of adjustment and revision also reflects the plaintiff’s aesthetic choices and individual judgment. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, it can be concluded that the images in question were independently created by the plaintiff, reflecting his or her individual expression, thus satisfying the requirement of “originality.” The images in question are aesthetically significant two-dimensional works of art composed of lines and colors, classified as works of fine art, and protected by copyright law. Regarding the ownership of the rights to the works in question, copyright law stipulates that authors are limited to natural persons, legal persons, or unincorporated organizations. Therefore, an artificial intelligence model itself cannot constitute an author under Chinese copyright law. The plaintiff configured the AI model in question as needed and ultimately selected the person who created the images in question. The images in question were directly generated based on the plaintiff’s intellectual input and reflect the plaintiff’s personal expression. Therefore, the plaintiff is the author of the images in question and enjoys the copyright to the images in question. The defendant, without permission, used the images in question as illustrations and posted them on his own account, allowing the public to access them at a time and location of his choosing. This infringed the plaintiff’s right to disseminate the images on the Internet. Furthermore, the defendant removed the signature watermark from the images in question, infringing upon the plaintiff’s right of authorship and should bear liability for infringement. The verdict ordered the defendant, Liu XX, to apologize and compensate for economic losses. Neither party appealed the verdict, which has since come into effect.

[Typical Significance]

This case clarifies that content generated by humans using AI, if it meets the definition of a work, should be considered a work and protected by copyright law. Furthermore, the copyright ownership of AI-generated content can be determined based on the original intellectual contribution of each participant, including the developer, user, and owner. While addressing new rights identification challenges arising from technological change, this case also provides a practical paradigm for institutional adaptation and regulatory responses to the judicial review of AI-generated content, demonstrating its guiding and directional significance. This case was selected as one of the top ten nominated cases for 2024 to promote the rule of law in the new era, one of the ten most influential events in China’s digital economy development and rule of law in 2024, and one of the top ten events in China’s rule of law implementation in 2023.

Case II: Yin XX v. A Certain Intelligent Technology Company, et al., Personal Rights Infringement Dispute

—Can the Rights of a Natural Person’s Voice Extend to AI-Generated Voices?

[Basic Facts]

Plaintiff Yin XX, a voice actor, discovered that works produced using his voice acting were widely circulated on several well-known apps. After audio screening and source tracing, it was discovered that the voices in these works originated from a text-to-speech product on a platform operated by the first defendant, a certain intelligent technology company. The plaintiff had previously been commissioned by the second defendant, a cultural media company, to record a sound recording, which held the copyright. The second defendant subsequently provided the audio of the recording recorded by the plaintiff to the third defendant, a certain software company. The third defendant used only one of the plaintiff’s recordings as source material, subjected it to AI processing, and generated the text-to-speech product in question. The product was then sold on a cloud service platform operated by the fourth defendant, a certain network technology company. The first defendant, a certain intelligent technology company, entered into an online services sales contract with the fifth defendant, a certain technology development company. The fifth defendant placed an order with the third defendant, which included the text-to-speech product in question. The first defendant, the certain intelligent technology company, used an application programming interface (API) to directly access and generate the text-to-speech product for use on its platform without any technical processing. The plaintiff claimed that the defendants’ actions had seriously infringed upon the plaintiff’s voice rights and demanded that Defendant 1, a certain intelligent technology company, and Defendant 3, a certain software company, should immediately cease the infringement and apologize. The plaintiff requested the five defendants compensate the plaintiff for economic and emotional losses.

[Judgment]

The court held that a natural person’s voice, distinguished by its voiceprint, timbre, and frequency, possesses unique, distinctive, and stable characteristics. It can generate or induce thoughts or emotions associated with that person in others, and can publicly reveal an individual’s behavior and identity. The recognizability of a natural person’s voice means that, based on repeated or prolonged listening, the voice’s characteristics can be used to identify a specific natural person. Voices synthesized using artificial intelligence are considered recognizable if they can be associated with that person by the general public or the public in relevant fields based on their timbre, intonation, and pronunciation style. In this case, Defendant No. 3 used only the plaintiff’s personal voice to develop the text-to-speech product in question. Furthermore, court inspection confirmed that the AI voice was highly consistent with the plaintiff’s voice in terms of timbre, intonation, and pronunciation style. This could evoke thoughts or emotions associated with the plaintiff in the average person, allowing the voice to be linked to the plaintiff and, therefore, identified. Defendant No. 2 enjoys copyright and other rights in the sound recording, but this does not include the right to authorize others to use the plaintiff’s voice in an AI-based manner. Defendant No. 2 signed a data agreement with Defendant No. 3’s company, authorizing Defendant No. 3 to use the plaintiff’s voice in an AI-based manner without the plaintiff’s informed consent, lacking any legal basis for such authorization. Therefore, Defendants No. 2 and No. 3’s defense that they had obtained legal authorization from the plaintiff is unsustainable. Defendants No. 2 and No. 3 used the plaintiff’s voice in an AI-based manner without the plaintiff’s permission, constituting an infringement of the plaintiff’s voice rights. Their infringement resulted in the impairment of the plaintiff’s voice rights, and they bear corresponding legal liability. Defendants No. 1, No. 4, and No. 5 were not subjectively at fault and are not liable for damages. Therefore, damages are determined based on a comprehensive consideration of the defendants’ infringement, the value of similar products in the market, and the number of views. Verdict: Defendants 1 and 3 shall issue written apologies to the plaintiff, and Defendants 2 and 3 shall compensate the plaintiff for economic losses. Neither party appealed the verdict, and the judgment has entered into force.

[Typical Significance]

This case clarifies the criteria for determining whether sounds processed by AI technology are protected by voice rights, establishes behavioral boundaries for the application of new business models and technologies, and helps regulate and guide the development of AI technology toward serving the people and promoting good. This case was selected by the Supreme People’s Court as a typical case commemorating the fifth anniversary of the promulgation of the Civil Code, a typical case involving infringement of personal rights through the use of the Internet and information technology, and one of the top ten Chinese media law cases of 2024.

Case III: Li XX v. XX Culture Media Co., Ltd., Internet Infringement Liability Dispute Case

—Using AI-synthesized celebrity voices for “selling products” without the rights holder’s permission constitutes infringement, and the commissioned promotional merchant shall bear joint and several liability.

[Basic Facts]

Plaintiff Li holds a certain level of fame and social influence in the fields of education and childcare. In 2024, Plaintiff Li discovered that Defendant XX Culture Media Co., Ltd. was promoting several of its family education books on an online platform store using videos of Plaintiff Li’s public speeches and lectures, accompanied by an AI-synthesized voice that closely resembled the Plaintiff’s voice. Plaintiff argued that the Defendant’s unauthorized use of Plaintiff’s portrait and AI-synthesized voice in promotional products closely associated the Plaintiff’s persona with the target audience of the commercial promotion, misleading consumers into believing the Plaintiff was the spokesperson or promoter for the books. The Defendant exploited the Plaintiff’s persona, professional background, and social influence to attract attention and increase sales, thereby infringing upon the Plaintiff’s portrait and voice rights. As a book seller, the defendant and the video publisher (a live streamer) had a commission relationship, jointly completing sales activities. The defendant had the obligation and ability to review the live streamer’s videos and should bear tort liability, including an apology and compensation for losses, for the publication of the video in question.

[Judgment]

The court held that the video in question used the plaintiff, Li’s portrait and AI-synthesized voice. This voice was highly consistent with Li’s own voice in timbre, intonation, and pronunciation style. Considering Li’s fame in the education and parenting fields, the video in question promoted family education books, making it easier for viewers to connect the relevant content in the video with Li. It can be determined that a certain range of listeners could establish a one-to-one correspondence between the AI-synthesized voice and the plaintiff himself. Therefore, the voice in question fell within the scope of protection of Li’s voice rights. The promotional video in question extensively used the plaintiff’s portrait and synthesized voice, without the plaintiff’s authorization. Therefore, the publication of the video in question constituted an infringement of the plaintiff’s portrait and voice rights. Defendant XX Culture Media Co., Ltd. and the video publisher (a live streamer) entered into a commissioned promotion relationship in accordance with the platform’s rules and service agreements. They jointly published the video in question for the purpose of promoting the defendant’s book and generating corresponding revenue. Furthermore, the defendant, based on the platform’s rules and management authority, possessed the ability to review and manage the video in question. Given that the video in question extensively used the plaintiff’s likeness and synthesized a simulated voice, the defendant should have had a degree of foresight regarding the potential copyright infringement risks posed by the video and exercised reasonable scrutiny to determine whether the video had been authorized by the plaintiff. However, the evidence in the case demonstrates that the defendant failed to exercise due diligence in its review. Therefore, defendant XX Culture Media Co., Ltd. should bear joint and several liability with the video publisher for publishing the infringing video. The judgment ordered defendant XX Culture Media Co., Ltd. to apologize to plaintiff Li and compensate for economic losses and reasonable expenses incurred in defending its rights. The judgment dismissed plaintiff Li’s other claims. Neither party appealed the verdict, and the judgment has entered into force.

[Typical Significance]

With the rapid development of generative artificial intelligence technology, the “cloning” and misuse of celebrity voices has become increasingly difficult to distinguish between genuine and fake, leading to widespread audio copyright infringement and significant consumer misinformation. This case clarifies that as long as the voice of a natural person synthesized using AI deep synthesis technology can enable the general public or the public in relevant fields to identify a specific natural person based on its timbre, intonation, pronunciation style, etc., it is identifiable and should be included in the scope of protection of the natural person’s voice rights. At the same time, in the legal relationship where merchants entrust video publishers to promote products, the platform merchant, as the entrusting party and actual beneficiary, has a reasonable review obligation to review the promotional content published by its affiliated influencers. Merchants cannot be exempted from liability simply on the grounds of “passive cooperation” or “no participation in production.” If they fail to fulfill their duty of care in review, they must bear joint and several liability with the influencers who promote products. This provides normative guidance for standardizing e-commerce promotion behavior, strengthening the main responsibilities of merchants, and governing the chaos of AI “voice substitution”, promoting the positive development of artificial intelligence and deep synthesis technology.

Case IV: Liao v. XX Technology and Culture Co., Ltd., Internet Infringement Liability Dispute Case

—Unauthorized “AI Face-Swapping” of Videos Containing Others’ Portraits, Constituting an Infringement of Others’ Personal Information Rights

[Basic Facts]

The plaintiff, Liao, is a short video blogger specializing in ancient Chinese style, with a large online following. The defendant, XX Technology and Culture Co., Ltd., without his authorization, used a series of videos featuring the plaintiff to create face-swapping templates, uploaded them to the software at issue, and provided them to users for a fee, profiting from the process. The plaintiff claims the defendant’s actions infringe upon his portrait rights and personal information rights and demands a written apology and compensation for economic and emotional damages. The defendant, XX Technology and Culture Co., Ltd., argues that the videos posted on the defendant’s platform have legitimate sources and that the facial features do not belong to the plaintiff, thus not infringing the plaintiff’s portrait rights. Furthermore, the “face-swapping technology” used in the software at issue was actually provided by a third party, and the defendant did not process the plaintiff’s personal information, thus not infringing the plaintiff’s personal information rights. The court found that the face-swapping template videos at issue shared the same makeup, hairstyle, clothing, movements, lighting, and camera transitions as the series of videos created by the plaintiff, but the facial features of the individuals featured were different and did not belong to the plaintiff. The software in question uses a third-party company’s service to implement face-swapping functionality. Users pay a membership fee to unlock all face-swapping features.

[Judgment]

The court held that the key to determining whether portrait rights have been infringed lies in recognizability. Recognizability emphasizes that the essence of a portrait is to point to a specific person. While the scope of a portrait centers around the face, it may also include unique body parts, voices, highly recognizable movements, and other elements that can be associated with a specific natural person. In this case, although the defendant used the plaintiff’s video to create a video template, it did not utilize the plaintiff’s portrait. Instead, it replaced the plaintiff’s facial features through technical means. The makeup, hairstyle, clothing, lighting, and camera transitions retained in the template are not inseparable from a specific natural person and are distinct from the natural personality elements of a natural person. The subject that the general public identifies through the replaced video is a third party, not the plaintiff. Furthermore, the defendant’s provision of the video template to users did not vilify, deface, or falsify the plaintiff’s portrait. Therefore, the defendant’s actions did not constitute an infringement of the plaintiff’s portrait rights. However, the defendant collected videos containing the plaintiff’s facial information and replaced the plaintiff’s face in those videos with a photo provided by the defendant. This synthesis process required algorithmically integrating features from the new static image with some facial features and expressions from the original video. This process involved the collection, use, and analysis of the plaintiff’s personal information, constituting the processing of the plaintiff’s personal information. The defendant processed this information without the plaintiff’s consent, thus infringing upon the plaintiff’s personal information rights. If the defendant infringes upon the creative work of others by using videos produced by others without authorization, the relevant rights holder should assert their rights. The judgment ordered the defendant to issue a written apology to the plaintiff and compensate the plaintiff for emotional distress. Neither party appealed the verdict, and the judgment has entered into force.

[Typical Significance]

This case, centered on the new business model of “AI face-swapping,” accurately distinguished between portrait rights, personal information rights, and legitimate rights based on labor and creative input in the generation of synthetic AI applications. This approach not only safeguards the legitimate rights and interests of individuals, but also leaves room for the development of AI technology and emerging industries, and provides a valuable opportunity for service providers.

Case V: Tang v. XX Technology Co., Ltd., Internet Service Contract Dispute Case

—An online platform using algorithmic tools to detect AI-generated content but failing to provide reasonable and appropriate explanations should be held liable for breach of contract.

[Basic Facts]

Plaintiff Tang posted a 200-word text on an online platform operated by defendant XX Technology Co., Ltd., stating, “Working part-time doesn’t make you much money, but it can open up new perspectives… If you’re interested in learning to drive and plan to drive in the future, you can do it during your free time during your vacation… After work, you won’t have much time to get a license.” The platform operated by defendant XX Technology Co., Ltd. classified the content as a violation of “containing AI-generated content without identifying it,” hid it, and banned the user for one day. Plaintiff Tang’s appeal was unsuccessful. He argued that he did not use AI to create content and that defendant XX Technology Co., Ltd.’s actions constituted a breach of contract. He requested the court to order the defendant to revoke the illegal actions of hiding the content and banning the account for one day, and to delete the record of the illegal actions from its backend system.

[Judgment]

The court held that when internet users create content using AI tools and post it to online platforms, they should label it truthfully in accordance with the principle of good faith. The defendant issued a community announcement requiring creators to proactively use labels when posting content containing AIGC. For content that fails to do so, the platform will take appropriate measures to restrict its circulation and add relevant labels. Using AI-generated content without such labels constitutes a violation. The plaintiff is a registered user of the platform, and the aforementioned announcement is part of the platform’s service agreement. The defendant has the right to review and address user-posted content as AI-generated and synthetic content in accordance with the agreement. Generally, the plaintiff should provide preliminary evidence, such as manuscripts, originals, source files, and source data, to prove the human nature of the content. However, in this case, the plaintiff’s responses were created in real time, making it objectively impossible to provide such evidence. Therefore, it is neither reasonable nor feasible for the plaintiff to provide such evidence. The defendant concluded that the content in question was AI-generated and synthetic based on the results of the algorithmic tool. The defendant is both the controller and judge of the algorithmic tool, controlling the algorithmic tool’s operation and review results. The defendant should provide reasonable evidence or explanation for this fact. Although the defendant provided the algorithm’s filing information, its relevance to the dispute could not be confirmed. The defendant failed to adequately explain the algorithm’s decision-making basis and results, nor to rationally justify its determination that the content in question was AI-generated and synthesized. The defendant should bear liability for breach of contract for its handling of the account in question without factual basis. The defendant’s standard for manual review required highly human emotional characteristics, and this judgment lacked scientific basis, persuasiveness, or credibility. The court ordered the defendant to repost the content and delete the relevant backend records. The defendant appealed the first-instance judgment but later withdrew the appeal, and the first-instance judgment stood.

[Typical Significance]

This case is a valuable exploration of the labeling, platform identification, and governance of AI-generated content within the context of judicial review. On the one hand, it affirms the positive role of online content service platforms in using algorithmic tools to review and process AI-generated content and fulfill their primary responsibility as information content managers. On the other hand, it recognizes the obligation of online content service platforms to adequately explain the results of automated algorithmic decisions in the context of live text creation, and establishes a standard for the level of explanation required during judicial review. Through judicial case-by-case adjudication, this case rationally distributes the burden of proof between online content service platforms and users, promotes online content service platforms to improve the recognition and decision-making capabilities of algorithms, and effectively improves the level of artificial intelligence information content governance.

Case VI: Cheng v. Sun Online Infringement Liability Dispute Case

—Using AI Software to Parody and Deface Others’ Portraits Consists of Personality Rights Infringement

[Basic Facts]

Plaintiff Cheng and defendant Sun were both members of a photography exchange WeChat group. Without Cheng’s consent, defendant Sun used AI software to create an anime-style image of Cheng, showing her as a scantily clad woman, from Cheng’s WeChat profile photo. He then sent the image to the group. Despite repeated attempts by plaintiff Cheng to dissuade him, defendant Sun continued to use the AI software to create an anime-style image of Cheng, showing her as a scantily clad woman with a distorted figure, and sent it to plaintiff via private WeChat messages. Plaintiff Cheng believes that the allegedly infringing images, sent by defendant Sun to groups and private messages, are recognizable as the plaintiff’s own image and contain significant sexual connotations and derogatory qualities, thereby diminishing her public reputation and infringing her portrait rights, reputation rights, and general personality rights. Plaintiff Cheng therefore demands an apology and compensation for emotional and economic losses.

[Judgment]

The court held that the allegedly infringing image posted by defendant Sun in the WeChat group was generated by AI using plaintiff Cheng’s WeChat profile picture without authorization. The image closely resembled the plaintiff Cheng’s appearance in terms of facial shape, posture, and style. WeChat group members were able to identify the plaintiff as the subject of the allegedly infringing image based on the appearance of the person and the context of the group chat. Therefore, the defendant’s group posting constituted an infringement of the plaintiff’s portrait rights. The plaintiff’s personal portrait displayed through her WeChat profile picture served as an identifier of her online virtual identity. The defendant’s use of AI software to generate the allegedly infringing image transformed the plaintiff’s well-dressed WeChat profile picture into an image revealing her breasts. This triggered inappropriate discussion within the WeChat group targeting the plaintiff and objectively led to vulgarized evaluations of her by others, constituting an infringement of her portrait rights and reputation rights. Furthermore, the defendant, Sun, used AI software to create an image of the plaintiff, Cheng, using her WeChat profile picture to create a picture with wooden legs and even three arms. The figure in the image clearly does not conform to the basic human anatomy, and the chest is also exposed. The defendant’s private message of these images to the plaintiff inevitably caused psychological humiliation, violated her personal dignity, and constituted an infringement of her general personality rights. The judgment ordered Sun to publicly apologize to Cheng and compensate her for emotional distress. Neither party appealed the verdict, and the judgment has entered into force.

[Typical Significance]

In this case, the court found that the unauthorized use of AI software to spoof and vilify another person’s portrait constituted an infringement of that person’s personality rights. The court emphasized that users of generative AI technology must abide by laws and administrative regulations, respect social morality and ethics, respect the legitimate rights and interests of others, and refrain from endangering the physical and mental health of others. This court clarified the behavioral boundaries for ordinary internet users using generative AI technology, and has exemplary significance for strengthening the protection of natural persons’ personality rights in the era of artificial intelligence.

Case VII: A Technology Co., Ltd. and B Technology Co., Ltd. v. Sun XX and X Network Technology Co., Ltd., Copyright Ownership and Infringement Dispute

—Original Avatar Images Constitute Works of Art

[Basic Facts]

Virtual Digital Humans [avatars] A and B were jointly produced by four entities, including plaintiff A Technology Co., Ltd. and plaintiff X Network Technology Co., Ltd. Plaintiff A Technology Co., Ltd. is the copyright owner, and plaintiff X Network Technology Co., Ltd. is the licensee. Virtual Digital Human A has over 4.4 million followers across various platforms and was recognized as one of the eight hottest events of the year in the cultural and tourism industries in 2022. The two plaintiffs claimed that the images of Virtual Humans A and B constitute works of art. Virtual Human A’s image was first published in the first episode of the short drama “Thousand ***,” and Virtual Human B’s image was first published on the Weibo account “Zhi****.” After resigning, Sun XX, an employee of one of the co-creation units, sold models of Virtual Humans A and B on a model website operated by defendant X Network Technology Co., Ltd. without authorization, infringing the two plaintiffs’ rights to reproduce and disseminate the virtual human images. As the platform provider, defendant X Network Technology Co., Ltd. failed to fulfill its supervisory responsibilities and should bear joint and several liability with defendant Sun XX.

[Judgment]

The court held that the full-body image of virtual human A and the head image of virtual human B were not directly derived from real people, but were created by a production team. They possess distinct artistic qualities, reflecting the team’s unique aesthetic choices and judgment regarding line, color, and specific image design. They meet the requirements of originality and constitute works of art. The defendant, Sun, published the allegedly infringing model on a model website. The model’s facial features, hairstyle, hair accessories, clothing design, and overall style, particularly in terms of the combination of original elements in the copyrighted work, are identical or similar to the virtual human A and virtual human B in the copyrighted work. This constitutes substantial similarity and infringes the plaintiffs’ right to disseminate the works through information networks. Taking into account factors such as the specific type of service provided by the defendant, the degree of interference with the content in question, whether it directly obtained economic benefits, the fame of the copyrighted work, and the popularity of the copyrighted content, the defendant, as a network service provider, did not commit joint infringement. Virtual human figures carry multiple rights and interests. This case only determines the rights and interests in the copyrighted work. The amount of economic compensation in this case is determined by comprehensively considering the type of rights sought to be protected, their market value, the subjective fault of the infringer, the nature and scale of the infringing acts, and the severity of the damages. Verdict: Defendant Sun was ordered to compensate the two plaintiffs for their economic losses. Defendant Sun appealed the first-instance judgment. The second-instance court dismissed the appeal and upheld the original judgment.

[Typical Significance]

This case concerns the legal attributes and originality of virtual digital human images. Virtual digital humans consist of two components: external representation and technical core, possessing a digital appearance and human-like functions. Regarding external representation, if a virtual human embodies the production team’s unique aesthetic choices and judgment regarding lines, colors, and specific image design, and thus meets the requirements for originality, it can be considered a work of art and protected by copyright law. This case provides a reference for similar adjudications, contributing to the prosperity of the virtual digital human industry and the development of new-quality productivity.

Case VIII: He v. Artificial Intelligence Technology Co., Ltd., a Case of Online Infringement Liability Dispute

—Creating an AI avatar of a natural person without consent constitutes an infringement of personality rights

[Basic Facts]

A certain artificial intelligence technology company (hereinafter referred to as the defendant) is the developer and operator of a mobile accounting software. Users can create their own “AI companions” within the software, setting their names and profile pictures, and establishing relationships with them (e.g., boyfriend/girlfriend, sibling, mother/son, etc.). He, a well-known public figure, was set as a companion by numerous users within the software. When users set “He” as a companion, they uploaded numerous portrait images of He to set their profile pictures and also set relationships. The defendant, through algorithmic deployment, categorized the companion “He” based on these relationships and recommended this character to other users. To make the AI character more human-like, the defendant also implemented a “training” algorithm for the AI character. This involves users uploading interactive content such as text, portraits, and animated expressions, with some users participating in review. The software then screens and categorizes the content to create the character data. The software can push relevant “portrait emoticons” and “sultry phrases” to users during conversations with “Ms. He,” based on topic categories and the character’s personality traits, creating a user experience that evokes a genuine interaction with the real person. The plaintiff claims that the defendant’s actions infringe upon the plaintiff’s right to name, right to likeness, and general personality rights, and therefore brought the case to court.

[Judgment]

The court held that the defendant’s actions constitute an infringement of the plaintiff’s right to name, right to likeness, and general personality rights. Under the defendant’s software’s functionalities and algorithmic design, users used Ms. He’s name and likeness to create virtual characters and interactive corpus materials. This projected an overall image, a composite of Ms. He’s name, likeness, and personality traits, onto the AI character, creating Ms. He’s virtual image. This constitutes a use of Ms. He’s overall personality, including her name and likeness. The defendant’s use of Ms. He’s name and likeness without her permission constitutes an infringement of his right to name and likeness. At the same time, users can establish virtual identities with the AI character, setting any mutual titles. By creating linguistic material to “tune” the character, the AI character becomes highly relatable to a real person, allowing users to easily experience a genuine interaction with Ms. He. This use, without Ms. He’s consent, infringes upon her personal dignity and personal freedom, constituting an infringement of her general personal rights and interests. Furthermore, the services provided by the software in question are fundamentally different from technical services. The defendant, through rule-setting and algorithmic design, organized and encouraged users to generate infringing material, co-creating virtual avatars with them, and incorporating them into user services. The defendant’s product design and algorithmic application encouraged and organized the creation of the virtual avatars in question, directly determining the implementation of the software’s core functionality. The defendant is no longer a neutral technical service provider, but rather bears liability for infringement as a network content service provider. Judgment: The defendant publicly apologizes to the plaintiff and compensates the plaintiff for emotional and economic losses. The defendant appealed the first-instance judgment but later withdrew the appeal, and the first-instance judgment came into effect. [Typical Significance]

This case clarifies that a natural person’s personality rights extend to their virtual image. The unauthorized creation and use of a natural person’s virtual image constitutes an infringement of that person’s personality rights. Internet service providers, through algorithmic design, substantially participate in the generation and provision of infringing content and should bear tort liability as content service providers. This case is of great significance in strengthening the protection of personality rights and has been selected by the Supreme People’s Court as a “Typical Civil Case on the Judicial Protection of Personality Rights after the Promulgation of the Civil Code” and a reference case for Beijing courts.

The original text can be found here: 北京互联网法院涉人工智能典型案例(Chinese only).

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms1 month ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers3 months ago

Jobs & Careers3 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Funding & Business3 months ago

Funding & Business3 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries