When kids use AI to cheat, are they gaming the system or are they ahead of the curve?

In January 2023 the New York City Department of Education banned its million-plus student body from using ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence “chatbot” that can perform a wide range of tasks such as long-form writing and artwork. Having taken a look at its capabilities after the release of ChatGPT 3.5 in November 2022 and seeing the potential for large-scale cheating and other negative impacts on student education, the NYC DOE prohibited its use for school work of any kind.

Who could blame it? Generative artificial intelligence had just broken through a major societal, even human evolutionary, barrier. When Silicon Valley’s OpenAI publicly launched ChatGPT 3.5, the world was introduced to the beginning of true artificial intelligence — machines that could read and write in plain language as well as, or better than, most humans. The immediate implications across all societal sectors were profound, perhaps especially so in education. Kids could now make AI do their homework for them, and they didn’t even have to forfeit their lunch money.

Just five days after the launch of ChatGPT 3.5, a million people had used it. In one month, the number of users bloomed to 57 million. The capabilities of this new AI were astonishing. It was far more robust than a Google search. This was a new digital “intelligence” that could create long-form, human-like responses from plain-language instructions (called prompts).

And, it was just the beginning. New releases from ChatGPT and its competitors, like Google’s Gemini and Microsoft’s Copilot, are rolled out every few months, each one seeming to have exponentially greater capabilities than the last. In little more than two years since ChatGPT 3.5, we’ve moved quickly from text-based AI to astoundingly sophisticated image and video generation. AI can already read, write, compute, and illustrate better (and far faster) than most humans. It can read and summarize a full-length novel in seconds, write code in minutes that would take a person months, describe images, create short animated films, and, yes, write convincing academic research papers. All you have to do is give it conversational instructions and maybe feed it some source material.

Banning students’ use of AI is a head-in-the-sand reaction. As with the public launch of the World Wide Web in 1991, the Rubicon has been crossed. Artificial intelligence has landed on humanity. Now, as its advancements continue to accelerate, resistance to the rise of AI is futile. Adaptation is paramount.

When ChatGPT 3.5 was released in late 2022, the immediate concern for educators and parents alike was its potential use for cheating. But cheating was only a single drop in the ocean of questions about AI’s impact on education, the foundational bedrock of human endeavor. At a deeper level, the advent of generative AI was a profound game changer for education, whether educators were ready for it or not.

Not all school districts took such drastic measures as New York. The administrators of St. Vrain Valley School District, here in Colorado, decided on a more observational approach. Lynn Gershman, SVVSD’s director of Academic Services, described the district’s approach to me over a Google Meet session. Also participating in the discussion was Randy Barber, SVVSD’s chief communications officer.

“Our leadership said, ‘No, let’s see what this is and see what happens,’” said Gershman. “How can we use the power of AI to educational advantage?”

I was intrigued by this more measured and optimistic perspective (in contrast to the New York ban), but I didn’t want to move past the problem of AI as a cheat buddy just yet. I asked Gershman if they had quantified the rate of AI-based cheating. She said it was difficult to measure, but in general, “if we give them (students) an app to cheat, they’re going to cheat.”

That seemed to answer the question well enough. Yes, kids are using AI to cheat. But, Gershman guided me to think more deeply about the subject, even about the very definition of cheating. Perhaps the student who seeks to make an AI chatbot do their work for them is not really cheating, but simply more savvy at using the technology available at their fingertips. The better question may be whether or not that “cheating” student is learning the subject matter and becoming more prepared for life in a brave new AI-driven world. That “cheating” student may be the one racing ahead of our antiquated thinking. To use a metaphor, maybe that “cheating” student is learning code while the student next to them is still stuck on Latin. Which student is more prepared for the future?

Gershman’s perspective seemed to be that trying to fight AI-based cheating head-on is a losing battle. “AI checkers don’t work,” she said. Gershman and her colleagues at SVVSD were more interested in adaptation — how to harness the power of AI for the benefit of educators and students alike.

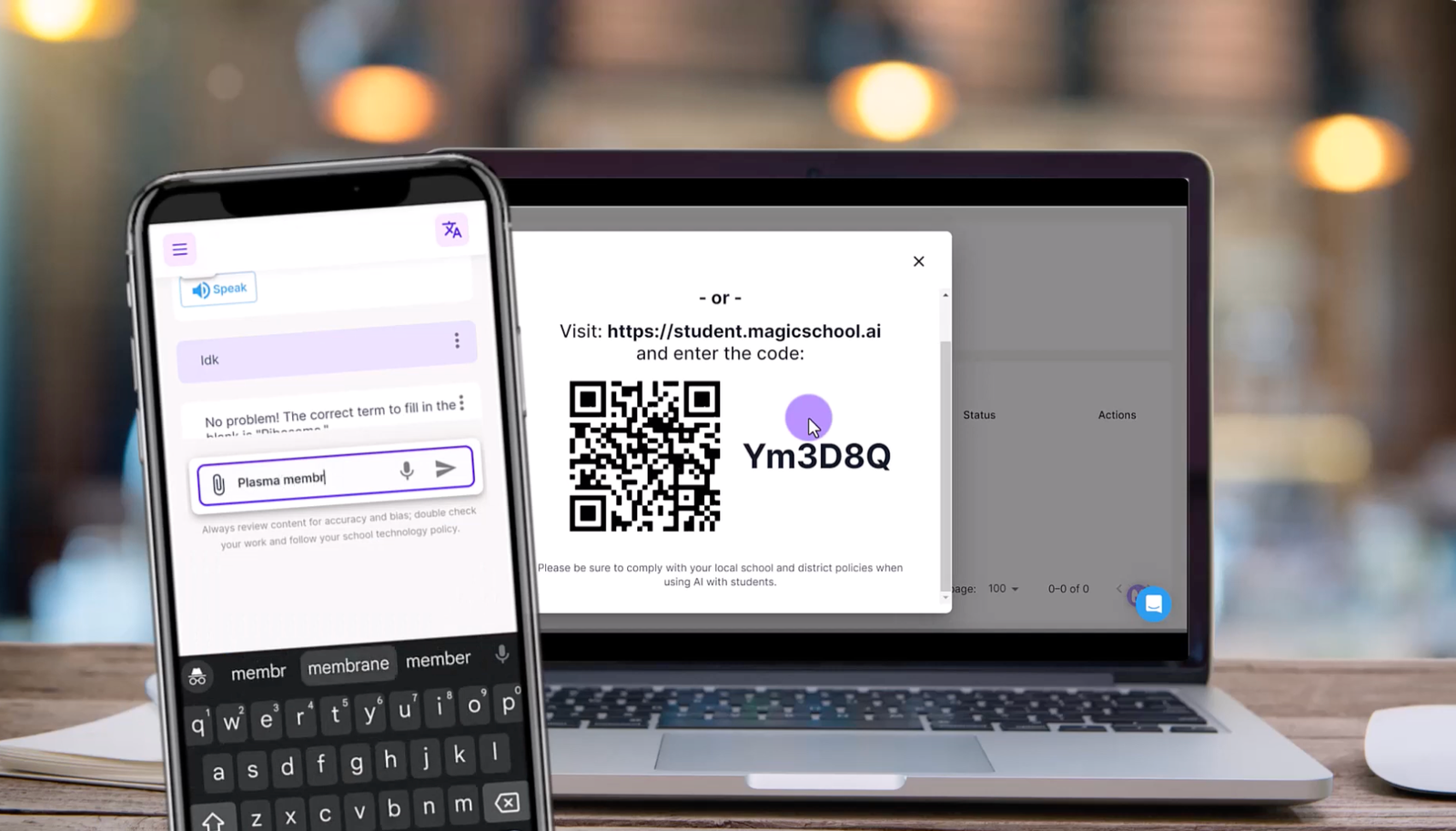

With this approach in mind, SVVSD decided to purchase access to an education-based AI platform called MagicSchool, a Denver-based start-up founded by a former teacher and principal. As SVVSD COO Randy Barber explained to me, the purchase of MagicSchool was a way for the district to simultaneously embrace the power of AI while also controlling it within a “walled garden.”

Gershman provided a quick virtual demo of MagicSchool for me. I immediately realized its potential as a powerful educational tool when, in less than a minute, MagicSchool created a scientific rubric for a 6th grade-level science assignment all based on a few simple prompts from Gershman. The system generated in seconds what would have taken a human teacher an hour or more to write manually. Any teacher can relate to the drudgery of out-of-classroom prepwork. If an AI system can do that heavy lifting, it can free up more of the teacher’s time and energy to focus on the human art of teaching and make the professional life of a teacher more rewarding in the process.

This capability, however, does not relieve the teacher of the need for a critical review of the AI-produced material. AI can, and often does, get it wrong, a phenomenon known in the AI industry as “hallucination.” Just as students must not rely entirely on AI to do their work for them, teachers must validate the output of AI systems to ensure accuracy and intent.

As the demonstration showed, MagicSchool is designed for both teachers and students. For teachers, it’s like having a teaching assistant with superpowers. Teachers can use the tool to quickly create lesson plans, devise educational games, create scenario-based discussion starters, and so much more. It can also be used to quickly customize learning approaches for different students within the same classroom, opening up new opportunities to reach individual students in ways that are most effective for them.

“It’s the teachers who are embracing AI that make it exciting,” said Gershman. “We have a middle school art teacher who taught her students to use AI to create wraps for skateboards,” said Gershman. “A language arts teacher is asking kids to use AI to generate sentence starters (to help the writing process).” My own daughter is a prolific young writer of fantasy fiction, which I encourage, and she, too, has used AI, not to write for her, but to generate ideas. These are examples of how teachers and students alike can use AI to enhance teaching and learning and make it more interesting and effective. The idea is to control it and use it as just another tool rather than to fear it and futilely try to prohibit its use.

According to Gershman, the students only access MagicSchool when the teachers make it available, thereby controlling when and how it is used. As with the teacher portal, students have access to a whole matrix of tailored AI applications within the system, such as an AI tutor, which Gershman said has been particularly effective.

This sounds wonderful for the controlled classroom environment, but it doesn’t solve the issue of independent cheating on homework. Out-of-classroom work takes an increasingly larger share of a student’s efforts as they advance into high school. In higher education, where classroom attendance is often optional, the opportunities to use AI to cheat only increase. Once students are off-campus with access to personal computing devices and the internet, educational institutions lose much of that walled-garden control.

It will be the responsibility of educators to “AI proof” their methods, as Gershman put it. The balancing act is to figure out how to leverage the power of AI to improve education while ensuring that AI is not a replacement for knowledge gain and critical thinking. “The tension is,” Gershman told me, “How do we help teachers modify their practice to ensure their students are still learning?”

There are practical methods for this. The classroom is an equalizer where AI can be put aside while the teacher engages the class in discussion. The old tried-and-true pop quiz is another method. The point is to ensure that students not only learn new material but can also demonstrate its application in real-world scenarios, all under the guidance of a skilled educator. Students in this type of learning environment will quickly understand that using AI to do their work for them can be an embarrassing trap when called upon in the classroom by the teacher to expand on their AI-written essay.

As AI continues to advance, and in many cases supplant human-centric problem-solving, students may question the point of learning in general. This may sound absurd, but the idea that intellectual learning itself is becoming obsolete is a real consideration. I asked Gershman and Barber if they thought literacy itself was at risk of obsolescence. It may seem like a silly question, but when machines can read and write for us, what’s the point of doing it ourselves, besides perhaps the simple enjoyment of the creative process of reading and writing?

Barber and Gershman suggested that AI may actually enhance the importance of human literacy. The temptation of allowing machines to do our reading and writing for us may be a dangerous gamble. “It’s a conceptual leap,” said Barber, “for kids to learn how to read, write, and do basic math.” These foundational skills are about far more than being able to read a book, write a letter, or figure out how many carwashes you need to sell to fund your spring break trip.

Reading, writing, and arithmetic are the foundational skills that shape developing brains into powerhouses of intellect and emotion. The brain is a thinking muscle that needs exercise to thrive. Without the stimuli of reading and writing, our bulbs will get dim very quickly. If social media is brain rot, using AI as a replacement for basic literacy skills will be like mental rigor mortis. To put it another way, humans need literacy as a foundation of complex problem-solving and critical thinking. In the age of AI, it’s likely that emotional analysis and critical thinking skills will be elevated in importance, not diminished. When we are presented with a blurring line between the artificial and real worlds, critical thinking and adaptiveness become paramount. Ensuring that we teach those skills goes back to our educators—teachers and parents included.

New York City skyline, United Nation headquarters over the East River, Manhattan, Midtown at day time, NYC, USA. Technologies and education concept.

New York City Schools Reverse Course

Four months after the ban on ChatGPT, New York City Public Schools changed its policy, recognizing the new reality that “our students are participating in and will work in a world where understanding generative AI is crucial,” stated David C. Banks, the chancellor of New York City Public Schools as reported in Chalkbeat’s First Person: ChatGPT caught NYC schools off guard. Now, we’re determined to embrace its potential.

In his message, Banks wrote, “The knee-jerk fear and risk overlooked the potential of generative AI to support students and teachers… Our nation is potentially on the brink of a significant societal shift driven by generative artificial intelligence. We must make sure that this technology’s benefits are equitably distributed to prevent further widening of socioeconomic gaps in our country… We will also ensure that our students are supported by AI’s opportunities and prepared for the jobs of today and the future.”

The perspective expressed here by Banks represents the same acknowledgement that the leadership of SVVSD recognized earlier: Generative AI has arrived. It will play a significant role in our world and our lives from this point forward. Educators should recognize this reality and work towards its ethical integration into our educational systems and methods rather than a fear-based exclusion to the future detriment of our youth.

Heading blindly into the future with confidence

The accelerating advancement of technology, and AI in particular, is shortening the event horizon by which we can plan for the future. Let’s break that statement down a little. In past generations we could be relatively well assured that what our children learned in school would be applicable to the real world in their adult lives. Any societal event so profound as to fundamentally change how humanity operates was too distant to be overly concerned with in the classroom. We could see clearly enough the general lay of the land ahead of us.

This is no longer the case. Our world may be so profoundly changed by AI within a single generation that it is quickly becoming impossible for adults to confidently prepare children for a future that is now hidden beyond that rapidly nearing event horizon. Our view of the lay of the land ahead of us suddenly has limited range, and we are racing into the void with no brakes.

Gershman recognizes the rapidity with which technology is changing the scene. When I asked her if SVVSD had a long-term plan for AI, she said, “I don’t know how you can. Tech is changing too quickly to have policies. We have [evolving] guidelines.” This is a practical realization of the nature of the challenges and opportunities that AI is presenting.

But this should not be mistaken for a wait-and-see approach. Gershman and other leaders in education are being proactive about understanding AI, its impact on education, and how to adapt to and, as she says, leverage its power for the better. Gershman served on a committee for the Colorado Education Initiative to create state AI guidelines, resulting in a document called the Colorado Roadmap for AI in K-12 Education.

Using ChatGPT 4.0 to Summarize the Colorado Roadmap for AI in K-12 Education

It’s a lengthy document, so I decided to have ChatGPT summarize it for me. After uploading the document, my prompt was, “Can you write a 100-150-word summary of this document with six to 10 key bullet points?”

ChatGPT 4.0’s response to my request, as follows, was returned in less than ten seconds:

:

The Colorado Roadmap for AI in K-12 Education provides guidance for integrating artificial intelligence into teaching and learning across the state’s public schools. Developed collaboratively by over 100 educators, students, and policy leaders, the roadmap emphasizes AI’s potential to enhance learning experiences, support equity, and prepare students for future careers. It calls for thoughtful implementation guided by ethical standards, transparency, and community engagement. Key recommendations include updating graduation requirements to include AI literacy, supporting educators with professional development, and ensuring equitable access to AI tools and infrastructure. The roadmap promotes principles over rigid policies, encouraging flexibility in a rapidly evolving technological landscape.

Key Bullet Points:

- Developed by Colorado educators, students, and leaders over seven months

- Emphasizes AI’s role in personalizing and enhancing teaching and learning

- Prioritizes ethical AI use, transparency, and student data privacy

- Supports AI literacy as a core skill for future readiness

- Recommends equitable access to AI tools, especially for underserved communities

- Encourages ongoing teacher training and professional support

- Advocates stakeholder engagement and local control in policy development

- Highlights the need for continual review and adaptation of AI practices

- Includes practical tools like evaluation checklists and equity strategies

- Calls for collaboration across districts and state-level organizations

That’s not too bad, but I was hoping for some more specific information on the use of AI to cheat, so I wrote a follow-up prompt to that effect: “Thanks, can you pinpoint and summarize any parts of the document that address the use of AI by students to cheat?”

Another few seconds, and the response came:

Yes, the roadmap addresses concerns about AI-enabled cheating primarily in the context of ethical use and academic integrity. Here are the key points summarized from the document

- Ethical Considerations and Cheating Concerns

- Educator concern: A top concern among teachers is that students might misuse AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT) to complete assignments dishonestly (p. 16).

- Reality check: The document notes that AI detection tools are already becoming ineffective as AI advances.

- Recommended response: Instead of relying on detection tools, schools should:

- Teach students responsible AI use.

- Incorporate AI ethics into conduct policies.

- Guide students to reflect on their learning and skill development, encouraging integrity.

- Academic Integrity and Responsible Use

- The roadmap encourages rethinking academic integrity policies:

- Focus less on punishment and more on clear definitions of plagiarism in the AI era (p. 19).

- Educate students on how to use AI productively and verify its outputs.

- Emphasize student understanding and transparency, rather than banning AI outright.

- Student and Family Engagement

- Schools are urged to communicate openly with families about:

- What AI is and how it’s being used in schools.

- Guidelines for appropriate student use.

- The roadmap suggests student-involved acceptable use frameworks to help prevent misuse.

Bottom Line:

Rather than prohibiting AI outright, the roadmap favors education, guidance, and trust to prevent cheating and encourage responsible, ethical use of AI by students.

The subject of this article was narrow–focusing on the risk of students using AI to cheat on their schoolwork. But, my research and discussion with my sources quickly revealed a much bigger question: When machines can read, write, create, and compute for us, what’s the point of education in general, at least the way we think of it?

In pondering this question I’m reminded of how profoundly technology has already changed our lives, and yet we continue to adapt with it. If we were to take a little journey back in time to the mid-1800’s, we would notice that the most valuable skills of the time are rarely learned by our youth today–such things as the proper way to rotate crops, or horse care. The most valuable skills of today would not be imaginable to the agrarian people of the mid-1800s.

Adapting to technology in education is nothing new. What is new is the pace of it, which brings me back to my event horizon analogy and how accelerating technological change is blinding our view into the future. Gershman and Barber presented an optimistic and enthusiastic perspective. But, the technological fog just off the bow of our human ship makes me uneasy. It seems to me that the most valuable skills we can teach our children are those of adaptability and critical thinking. In the age of artificial intelligence, our kids will need to learn how to keep their feet planted in reality.