AI Insights

Artificial intelligence and the wellbeing of workers

Previous work

Our paper builds on and extends recent research examining the impact of AI on labor market outcomes and worker well-being. Prior studies have largely found positive effects of AI exposure on employment and wages at the industry or occupational level. For example, Felten et al. (2019)22 document small wage gains in AI-exposed occupations in the US, while Gathmann and Grimm (2022)23 find a positive relationship between AI exposure and employment in Germany, particularly in the service sector. Acemoglu et al. (2022)20 analyze U.S. labor markets using establishment-level vacancy data from 2010 onward, finding rapid AI adoption, particularly in firms with tasks suited for automation. Their findings suggest that AI-exposed firms increase AI-related hiring while simultaneously reducing non-AI hiring and altering skill demands. Despite these firm-level shifts, they find no significant impact on overall employment or wage growth in AI-exposed industries and occupations, indicating that AI’s displacement effects may currently outweigh productivity-driven job creation. When examining the heterogeneity of results across occupations, Bonfiglioli et al. (2025)24 find evidence that AI exposure led to job losses across US commuting zones, particularly for low-skill and production workers, while benefiting high-wage and STEM occupations. Unlike other technologies, AI’s impact is driven by services rather than manufacturing, contributing to automation of jobs and rising inequality.

At the same time, researchers have raised concerns that AI could accelerate the erosion of middle-class job security by automating tasks without creating sufficient new roles for human workers25.Whether AI complements or displaces human labor depends not only on the extent of automation but also on which tasks are automated and which workers are affected26. In this regard, Brekelmans and Petropoulos (2020)27 highlight that mid-skilled occupations are among the most vulnerable to AI-driven disruption. However, some scholars suggest that AI can help reduce job performance inequalities by improving efficiency and decision-making support10,28.

While existing studies have extensively examined labor market effects of AI, relatively little attention has been paid to its broader impact on worker well-being. Our work addresses this gap, contributing to a growing body of research exploring the effects of automation technologies on workers’ health and psychological outcomes.

Previous research on the effects of automation on well-being has primarily examined industrial robots and mechanized systems13,29. However, AI represents a distinct form of automation, as it relies on computer-based learning and cognitive processing rather than physical manipulation9. Unlike traditional robotics, which primarily displaces routine manual tasks, AI has the potential to automate non-routine cognitive tasks that were once considered resistant to mechanization22,25,30. This shift suggests that AI may not only disrupt routine jobs but also reshape knowledge-based professions, placing even highly educated workers at risk of automation-driven changes. Moreover, as AI systems become more capable of complex reasoning, decision-making, and problem-solving, their impact on the labor market is likely to extend beyond simple task automation, influencing job design, skill requirements, and career trajectories across various industries.

The influence of AI on employee well-being may operate through multiple channels. On one hand, AI-driven automation can reduce physical strain in labor-intensive jobs, potentially improving physical health. On the other hand, AI adoption can increase cognitive and emotional demands in knowledge-intensive occupations, altering job content in ways that either enhance or undermine job satisfaction. Additionally, shifts in workplace dynamics—such as changes in perceived job security, workplace autonomy, and the sense of purpose derived from work—may further affect workers’ experiences with AI.

Worker attitudes toward AI remain mixed. Some global surveys indicate rising concerns about the consequences of AI on job opportunities31 yet a recent Pew study finds that US workers in AI-exposed industries do not perceive AI as an immediate threat32. AI has the potential to enhance productivity and complement human skills, but it can also displace workers in certain roles. As with past technological revolutions, the ultimate labor market impact of AI will depend on the evolving balance between complementarity and substitution between AI and human labor20,33,34. Moreover, AI alters the nature of work itself, influencing job satisfaction, professional identity, and the perceived dignity of labor35.

Whether the beneficial effects of AI on labor market outcomes offset or even outweigh its displacement effects remains an empirical question—particularly in the short term, as workers and labor markets undergo a period of transition and adaptation to this new general-purpose technology.

Conceptual framework

This study builds on task-based theories of technological change33,36, which conceptualize AI as a transformative force that reallocates tasks between humans and machines. Similarly to robots, AI automates routine and physically demanding tasks, enabling workers to transition into higher-skill, cognitively demanding roles. However, unlike robots, AI can also automatize non-routine tasks30. The dual role of AI—as both a complement and a substitute to human labor—is central to understanding its heterogeneous effects. In our context, complementarity arises when AI reduces physical strain and augments workers’ capabilities, enhancing productivity and job satisfaction. Conversely, substitutability occurs when AI displaces workers, increasing job insecurity and workplace anxiety.

AI adoption, as documented by Acemoglu et al. (2022)20, follows a pattern where firms with task structures conducive to AI integration experience substantial labor reconfigurations. While automation’s displacement effects have been widely studied, the role of AI in hazardous and physically strenuous occupations offers a distinct perspective on its labor market consequences. We hypothesize that AI’s integration into hazardous tasks—such as those involving exposure to toxic environments, heavy lifting, or repetitive strain—can reduce workplace injuries and long-term health risks. This hypothesis aligns with prior research on automation’s potential to enhance worker safety by shifting high-risk activities to machines, thereby improving physical well-being13.

Acemoglu et al. (2022)20 highlight that AI-exposed establishments tend to reduce overall hiring, indicating that productivity gains from AI do not necessarily lead to net job creation. This trend, coupled with AI’s ability to automate both routine and certain non-routine cognitive and abstract tasks, suggests that a broader range of workers—including those in knowledge-based professions—may experience job displacement pressures. Such uncertainty can have significant psychological consequences, as fears of automation-related job loss contribute to chronic stress, financial insecurity, and diminished workplace morale. The effects are likely to be unevenly distributed, disproportionately impacting low-wage workers while also altering career trajectories for higher-skilled professionals, ultimately reinforcing patterns of economic inequality across different skill levels.

Thus, while AI adoption holds promise for improving workplace safety and productivity, its net effect on worker well-being remains uncertain. Whether the benefits—such as reduced workplace hazards and improved job quality—outweigh the disruptions caused by job displacement and economic instability depends on how AI is integrated into labor markets. This duality underscores the need for policies that not only facilitate AI integration in ways that protect workers’ health but also address the economic and social ramifications of AI-driven labor shifts.

Furthermore, our study builds upon traditional job quality frameworks by examining AI-induced transformations in physical job intensity, cognitive demands, and health outcomes. While much of the public debate on digitalization has focused on job quantity (i.e., job creation vs. job loss), its effects on job quality are equally significant and warrant further attention37,38. Martin and Hauret (2022)37 identify six key dimensions of job quality commonly examined in the literature: labor income, workplace safety, working time and work-life balance, job security, skill development and training, and employment-related relationships and work motivation. Traditional models conceptualize job quality through physical, cognitive, and emotional dimensions. However, emerging technologies—especially AI—are reshaping these dimensions in profound ways. AI-driven workplace changes can lead to new forms of cognitive strain, shifts in workplace autonomy, and evolving skill demands, all of which have direct consequences for workers’ well-being. Further research is needed to fully understand how digitalization—particularly AI—modifies job demands, psychological stress, and long-term employment conditions.

AI technologies frequently automate repetitive, physically demanding, and hazardous tasks, thereby alleviating physical labor for workers. In manufacturing, AI-powered machinery has increasingly replaced tasks such as assembly-line work and heavy lifting, while in service industries, AI tools like virtual assistants reduce administrative workloads, complementing physical task reductions. As AI shifts job responsibilities from physical execution to supervisory or decision-making roles, the overall physical strain on workers declines. Empirical evidence supports this trend; for instance, Gihleb et al. (2022)13 document significant reductions in physically demanding work as automation becomes more prevalent. Using a physical burden metric from the SOEP, we examine the link between AI exposure and reduced physical job intensity.

Finally, our study engages with theories of institutional mediation13 to examine how labor market institutions shape AI’s effects on workers. Specifically, we hypothesize that Germany’s strong labor protections, high unionization rates, and employment legislation may moderate the adverse consequences of AI on worker well-being. Institutions that provide employment security, reskilling opportunities, and worker protections may buffer against the negative impacts of automation, reducing stress and job displacement fears. This contrasts with more flexible labor markets, where AI-induced disruptions may lead to greater economic precarity.

Our contribution

Our research highlights the importance of Germany’s unique institutional context, characterized by strong labor protections, extensive union representation, and comprehensive employment legislation. These factors, combined with Germany’s gradual adoption of AI technologies, create an environment where AI is more likely to complement rather than displace worker skills, mitigating some of the negative labor market effects observed in countries like the US. Germany’s institutional framework, marked by strong labor protections, widespread union representation, and comprehensive employment regulations, plays a crucial role in shaping the effects of AI adoption. These structural safeguards, along with the country’s more gradual integration of AI technologies, foster an environment where AI is more likely to enhance rather than replace worker skills, mitigating some of the negative labor market effects observed elsewhere. However, as Bonfiglioli et al. (2025)24 highlight, AI exposure has led to job losses in the US, particularly among low-skilled and production workers, while benefiting high-wage and STEM occupations. Given AI’s distinct impact on service industries rather than traditional manufacturing, workers in routine-intensive service sectors may still face heightened risks of displacement, even within Germany’s more protective labor market. These theoretically ambiguous effects make Germany a particularly interesting case for examining the interaction between AI adoption and labor market institutions, raising an important empirical question about the extent to which these protections can shield workers from displacement while enabling technological progress.

In addition, we explore heterogeneity in outcomes based on worker characteristics (e.g., gender, education, union membership) and regional differences (e.g., East vs. West Germany), offering a more granular perspective on the potential effects of AI on labor markets and worker well-being.

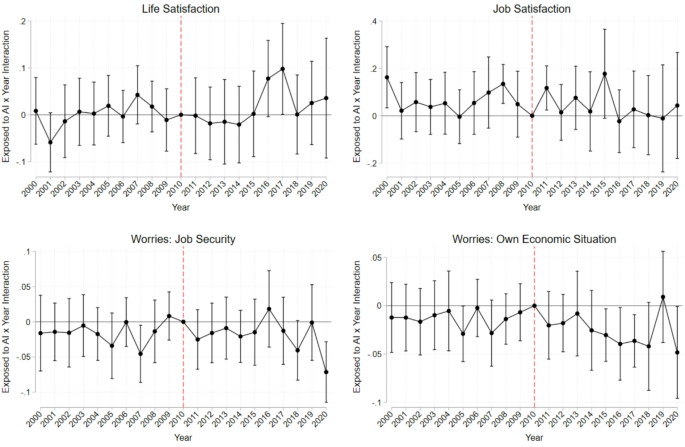

Unlike studies such as Nazareno and Schiff (2021) and Liu (2023)29,39, which rely on cross-sectional data and broad measures of automation exposure40, our analysis is uniquely AI-focused. We leverage the Webb measure of exposure to AI alongside a self-reported metric from the SOEP, ensuring a more precise assessment of the effects of AI on worker well-being and labor market dynamic. Using longitudinal data from the SOEP over the period 2000–2020, we employ an event study analysis and a DiD design to address selection bias and control for individual fixed effects. This methodological approach enables us to capture long-term trends and examine nuanced outcomes such as life satisfaction, mental health, and physical health—dimensions that have often been overlooked in prior research.

AI in Germany

The roll-out of AI in Germany accelerated only recently. As noted by Gathmann and Grimm (2022)23, patent applications for AI technologies started to grow strongly only after 2015, and more significantly in 2017 and 2018. The innovation survey conducted by ZEW- Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research provides a consistent longitudinal perspective on AI adoption in Germany18. Specifically, the most recent wave of the innovation survey contains information on AI adoption percentages for 2021. AI use was not widespread before 2010, and the rate of AI adoption was extremely low before 2016. To be conservative, we chose 2010 as the beginning of our treatment period. AI adoption rates have increased substantially over the last few years. While only 2% of firms adopted AI before 2016, this number rose to 6% in 2019 and 10% in 202118. Regarding the diffusion of AI across industries, the leading adopters of AI technology in 2019 were finance (24%) and IT (21%), followed by skilled services (18%) such as legal, architecture, consulting, and research. Conversely, the laggards in AI adoption include mining (1.6%), miscellaneous business services (2.3%), and transportation (5.3%). These cross-sectoral differences in AI adoption are qualitatively reflected in our individual-level data on AI exposure from the SOEP, with IT and finance being the most exposed (see Figure A.1 in the Appendix). As deatiled in Rammer et al. (2022), 75% of the firms in the finance sector that used AI technologies in 2019 began using AI in 2016. The share of the chemical and pharmaceutical sectors is 74%, whereas that of electronics and machines is 68%.

Increasing rates of AI adoption across German firms were accompanied by the German government’s investment in AI. In 2018, the German Federal Government launched its Artificial Intelligence Strategy and pledged to invest approximately 5 billion euros by 2025 in AI development. For these reasons, Germany is an interesting country for analyzing the effects of rising exposure to AI on the well-being and health of workers.

AI Insights

Artificial Intelligence Legal Holds: Preserving Prompts & Outputs

You are your company’s in-house legal counsel. It’s 3 PM on a Friday (because of course it is), and you’ve just received notice of impending litigation. Your first thought? “Time to issue a legal hold.” Your second thought, as you watch your colleague casually chatting with Claude about contract drafting? “Oh no… what about all the AI stuff?”

Welcome to 2025, where your legal hold obligations just got an AI-powered upgrade you never signed up for. This isn’t just theoretical hand-wringing. Companies are already being held accountable for incomplete AI-related preservation, and the costs are real — both in terms of litigation exposure and the scramble to retrofit compliance systems that never anticipated chatbots.

The Plot Twist Nobody Saw Coming

Remember when legal holds meant telling people not to delete their emails? The foundational duty to preserve electronically stored information (ESI) when litigation is “reasonably anticipated” remains the cornerstone of legal hold obligations. However, generative AI’s emergence has significantly complicated this well-established framework. Courts are increasingly making clear that AI-generated content, including prompts and outputs, constitutes ESI subject to traditional preservation obligations.

Those were simpler times. Now, every prompt your team types into ChatGPT, every AI-generated marketing copy, and yes, even that time someone asks Perplexity for restaurant recommendations during a business trip — it’s all potentially discoverable ESI.

Or so say several recent court decisions:

- In the In re OpenAI, Inc. Copyright Infringement Litigation MDL (SDNY), Magistrate Judge Ona T. Wang ordered OpenAI to preserve and segregate all output log data that would otherwise be deleted (whether deletion would occur by user choice or to satisfy privacy laws). Judge Sidney H. Stein later denied OpenAI’s objection and left the order standing (now on appeal to the Second Circuit). This is the clearest signal yet that courts will prioritize litigation preservation over default deletion settings.

- In Tremblay v. OpenAI (N.D. Cal.), the district court issued a sweeping order requiring OpenAI “to preserve and segregate all output log data that would otherwise be deleted on a going forward basis.” The Tremblay court dropped a truth bomb on us: AI inputs — prompts — can be discoverable.

- And although not AI-specific, recent chat-spoliation rulings (e.g., Google’s chat auto-delete practices) show that judges expect parties to suspend auto-delete once litigation is reasonably anticipated. These cases serve as analogs for AI chat tools.

Your New Reality Check: What Actually Needs Preserving?

Let’s break down what’s now on your preservation radar:

The Obvious Stuff:

- Every prompt typed into AI tools (yes, even the embarrassing ones)

- All AI-generated outputs used for business purposes

- The metadata showing who, what, when, and which AI model

The Not-So-Obvious Stuff:

- Failed queries and abandoned outputs (they still count!)

- Conversations in AI-powered Slack bots and Teams integrations

- That “quick question” someone asked Claude about a competitor

The “Are You Kidding Me?” Stuff:

- Deleted conversations (spoiler alert: they’re often not really deleted)

- Personal AI accounts used for work purposes

- AI-assisted research that never made it into final documents

Of course, knowing what to preserve is only half the battle. The real challenge? Actually implementing AI-aware legal holds when your IT department is still figuring out how to monitor these tools, your employees are using personal accounts for work-related AI, and new AI integrations appear in your tech stack on a weekly basis.

Next week, we’ll dive into the practical playbook for AI preservation — including the compliance frameworks that actually work, the vendor questions you should be asking, and why your current legal hold software might be more helpful than you think (or more useless than you fear).

P.S. – Yes, this blog post was ideated, outlined, and brooded over with the assistance of AI. Yes, we preserved the prompts. Yes, we’re practicing what we preach. No, we’re not perfect at it yet either.

AI Insights

AI firm Anthropic agrees to pay authors $1.5bn for pirating work

Artificial intelligence (AI) firm Anthropic has agreed to pay $1.5bn (£1.11bn) to settle a class action lawsuit filed by authors who said the company stole their work to train its AI models.

The deal, which requires the approval of US District Judge William Alsup, would be the largest publicly-reported copyright recovery in history, according to lawyers for the authors.

It comes two months after Judge Alsup found that using books to train AI did not violate US copyright law, but ordered Anthropic to stand trial over its use of pirated material.

Anthropic said on Friday that the settlement would “resolve the plaintiffs’ remaining legacy claims.”

The settlement comes as other big tech companies including ChatGPT-maker OpenAI, Microsoft, and Instagram-parent Meta face lawsuits over similar alleged copyright violations.

Anthropic, with its Claude chatbot, has long pitched itself as the ethical alternative among its competitors.

“We remain committed to developing safe AI systems that help people and organisations extend their capabilities, advance scientific discovery, and solve complex problems,” said Aparna Sridhar, Deputy General Counsel at Anthropic which is backed by both Amazon and Google-parent Alphabet.

The lawsuit was filed against Anthropic last year by best-selling mystery thriller writer Andrea Bartz, whose novels include We Were Never Here, along with The Good Nurse author Charles Graeber and The Feather Thief author Kirk Wallace Johnson.

They accused the company of stealing their work to train its Claude AI chatbot in order to build a multi-billion dollar business.

The company holds more than seven million pirated books in a central library, according to Judge Alsup’s June decision, and faced up to $150,000 in damages per copyrighted work.

His ruling was among the first to weigh in on how Large Language Models (LLMs) can legitimately learn from existing material.

It found that Anthropic’s use of the authors’ books was “exceedingly transformative” and therefore allowed under US law.

But he rejected Anthropic’s request to dismiss the case.

Anthropic was set to stand trial in December over its use of pirated copies to build its library of material.

Plaintiffs lawyers called the settlement announced Friday “the first of its kind in the AI era.”

“It will provide meaningful compensation for each class work and sets a precedent requiring AI companies to pay copyright owners,” said lawyer Justin Nelson representing the authors. “This settlement sends a powerful message to AI companies and creators alike that taking copyrighted works from these pirate websites is wrong.”

The settlement could encourage more cooperation between AI developers and creators, according to Alex Yang, Professor of Management Science and Operations at London Business School.

“You need that fresh training data from human beings,” Mr Yang said. “If you want to grant more copyright to AI-created content, you must also strengthen mechanisms that compensate humans for their original contributions.”

AI Insights

Duke University pilot project examining pros and cons of using artificial intelligence in college | National News

We recognize you are attempting to access this website from a country belonging to the European Economic Area (EEA) including the EU which

enforces the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and therefore access cannot be granted at this time.

For any issues, contact jgnews@jg.net or call 260-461-8773.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms4 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi