As AI literacy increasingly becomes a fundamental competency for future healthcare professionals, it is imperative that healthcare students are adequately prepared to navigate technological advancements in their future workplaces. To support this goal, assessing the current level of AI literacy among healthcare students is a necessary first step in designing targeted and effective educational interventions. In line with this objective, the present study explored healthcare students’ AI literacy and examined its associations with their attitudes toward AI, their intention to use AI in clinical contexts, and individual characteristics such as prior AI training and interest in AI.

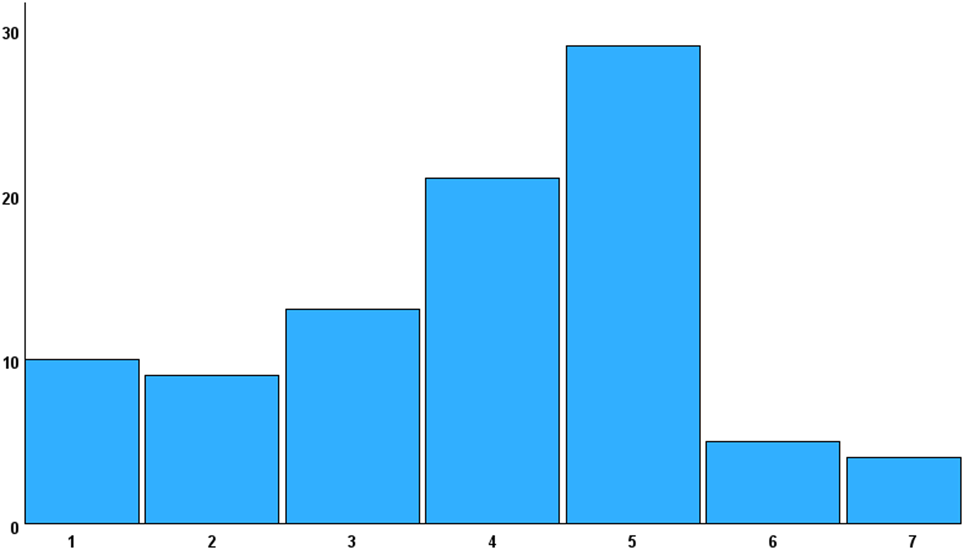

To address this aim, SNAIL was first validated through confirmatory factor analysis in the Korean context. During this process, seven items were excluded, resulting in a final version consisting of 24 items (SNAIL-KR), which was used for the analysis. The results revealed that students demonstrated slightly below-average levels of AI literacy. These findings are consistent with those of Laupichler et al. [6], who reported a comparable level of AI literacy among German medical students, with a total mean score of 3.76 (3.79 in the present study). In their study, critical appraisal also showed the highest mean score (M = 4.89, M = 4.64 in this study) and technical understanding the lowest (M = 2.63, M = 3.19 in this study), demonstrating the same pattern observed in the present study. The relatively higher scores in critical appraisal may reflect increased exposure to media coverage on issues such as data privacy, ethics, and AI-related risks. However, given that the highest subscale score was only marginally above the midpoint of 4, the findings collectively underscore the need for more comprehensive AI literacy education. This interpretation is further supported by the fact that 85.17% of participants reported receiving less than 30 h of AI-related training. Moreover, systematic reviews by Kimiafar et al. [30] and Mousavi Baigi et al. [2] similarly reported that although healthcare professionals and students generally expressed motivation to adopt AI, they had received insufficient training and tended to possess limited knowledge and skills in using AI. These findings reinforce the present study’s results, highlighting the urgent need to strengthen AI literacy education to better prepare future healthcare professionals.

In addition, participants overall exhibited positive attitudes toward AI. However, the mean score for negative attitudes (reverse scored) was also slightly above the neutral midpoint. This suggests a balance between favorable and cautious perspectives—students recognized the potential benefits of AI while also acknowledging its current limitations. This result is consistent with the findings of Seo and Ahn [23], who examined the attitudes of 230 Korean nursing students using the same scale. On a 5-point Likert scale, the mean for positive attitudes was 3.69, while that for negative attitudes was 3.07, reflecting a pattern similar to that observed in the present study. Similarly, Gordon et al.’s [1] scoping review on attitudes toward the application of AI in clinical medicine reported the coexistence of support for and concerns about AI among healthcare learners. Such concerns may influence learners to adopt a cautious stance toward AI applications. Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of directly addressing both the opportunities and concerns related to AI in future education and training programs.

Furthermore, the findings indicate that students with higher levels of AI literacy are more likely to hold positive attitudes toward AI—and vice versa. Among the subcategories, practical application showed the strongest correlation with positive attitudes, suggesting that students who view AI favorably are more inclined to engage with it in daily life. Critical appraisal was positively associated with positive attitudes and negatively associated with negative attitudes, with a notably stronger correlation for positive attitudes. This implies that the more students understand both the benefits and potential concerns of AI, the more likely they are to adopt a positive perspective. In addition, a positive association was observed between positive attitudes toward AI and prior AI training. Collectively, these results highlight the importance of structured AI literacy education that addresses both the advantages and potential risks associated with AI.

Regarding the intention to use AI in clinical contexts, participants reported scores slightly above the neutral midpoint. This intention was significantly associated with both AI literacy and positive attitudes toward AI. These findings demonstrate that AI literacy is a critical factor influencing students’ intention to use AI in clinical practice, while also confirming previous research showing a positive association between positive attitudes toward AI and the intention to use it [1, 13].

Additionally, both AI literacy and positive attitudes toward AI were significantly correlated with students’ interest in AI and their prior AI training, with stronger correlations observed for interest in AI than for prior training. Interest in AI was also significantly associated with the intention to use AI, whereas prior AI training did not show a significant correlation with this variable. Furthermore, among the subcategories of AI literacy, practical application exhibited a notably stronger correlation with students’ interest in AI than with their prior AI training. This suggests that students with higher interest in AI are more likely to engage with AI technologies in their daily lives, thereby reinforcing their AI literacy and fostering positive attitude AI. The influential role of interest in AI on AI literacy aligns with findings by Laupichler et al. [6], who reported that students’ interest in AI was more strongly association with AI literacy than previous training experience. Moreover, there was a notable difference in AI literacy between students with hardly any training and those with less than 30 h training or more than 30 h of training, with mean differences of 0.68 and 1.1 point, respectively. These findings highlight the potential impact of AI education and suggest that programs providing more than 30 h of training may be necessary to meaningfully enhance students’ AI literacy. While the lack of significant association between prior AI training and intention to use AI may be attributable to the small sample size, further research is needed to clarify this relationship. Overall, the findings suggest that fostering interest in AI may be particularly effective in promoting AI literacy and that educational interventions should aim to stimulate engagement and curiosity about AI especially through programs offering more than 30 h of training.

No significant differences were observed by gender, year of study, or major for any of the measured variables in this study. These findings differ from those reported by Laupichler et al. [6], who found that male students scored higher in AI literacy and that academic semester was significantly associated with AI literacy levels. Similarly, Hashish and Alnajjar [5], in a study assessing nursing students’ digital health literacy—defined as perceived competence in using digital health tools—found that senior students demonstrated higher literacy levels. In addition, Kwak et al. [13] reported that senior students exhibited significantly higher positive attitudes toward AI, and Sumengen et al. [20] found that male nursing students showed more positive attitudes toward AI, as both measured by the GAAIS.

This discrepancies between these previous findings and the current results cannot be fully explained in this study. However, one possible explanation for the lack of significant gender difference is that participation in this survey was voluntary, and response rate is low. Thus, students who chose to participate—regardless of gender—may have had a greater interest in AI than the general student population. In addition, the absence of significant differences by year of study may reflect the limited integration of AI-related content into the curriculum. As previously noted, AI education in Korea is typically offered only as elective courses during pre-medical phase, which may contribute to a lack of variation in AI literacy and attitudes across academic years. Alternatively, these nonsignificant results may be attributed to the relatively small sample size. Regarding the lack of significant differences by major, further investigation is needed to explore whether and how AI literacy varies across academic disciplines within healthcare education. Future studies with larger and more diverse samples across multiple disciplines in healthcare education are needed to confirm and extend these findings.

The findings of this study highlight the urgent need to systematically integrate AI literacy into healthcare curricula. Current training opportunities appear insufficient, with most students reporting minimal exposure to AI education. Given the observed increase in AI literacy among students with more than 30 h of AI training, this study highlights the value of structured programs of sufficient length. Training that exceeds 30 h may be especially effective in enhancing both AI literacy and positive attitudes toward AI. In addition, integrating AI content into core curricula—rather than offering it solely as electives—can promote more equitable and comprehensive learning experiences. Educators should also leverage students’ existing interest in AI as a foundation for enhancing AI literacy. Instructional programs should be deliberately designed to spark and sustain students’ interest in AI, for example, by incorporating hands-on activities using AI tools, and interdisciplinary projects that apply AI to solve real-world healthcare problems. Furthermore, given that students may approach AI with a cautious stance toward AI applications, AI literacy programs should explicitly address their concerns. Promoting open dialogue, encouraging critical reflection, and providing exposure to practical applications can help learners develop a balanced and informed perspective on the role of AI in clinical practice.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small. The response rate of online survey was very low likely due to an ongoing two-year collective leave of absence among Korean medical students, triggered by political issues. Additionally, the sample was drawn from a single institution in one geographic region, which limits the generalizability of the findings. However, although the participants may not be fully representative of all Korean healthcare students, medical students in Korea tend to form a relatively homogeneous group due to the highly standardized and competitive admission process. Moreover, given the curricular similarities across Korean medical schools, significant variation in AI literacy between institutions may be limited. Future studies with larger and more diverse samples from multiple institutions are essential to validate and expand upon these results. Nonetheless, the present study offers preliminary insights that may serve as a valuable baseline for further investigation into AI literacy and attitudes among healthcare students. In addition, multinational studies could provide useful comparative perspectives on how AI literacy varies across educational and cultural contexts. Longitudinal or intervention-based research examining the development of AI literacy over time may also inform the design of future curricula.

Second, the study relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to response bias and subjective interpretation. To enhance the validity of future findings, objective measures—such as knowledge-based assessments or evaluations of practical AI-related skills—should be incorporated alongside self-report instruments. Finally, the adapted SNAIL-KR scale demonstrated both feasibility and internal consistency. The results obtained using SNAIL-KR were comparable to those reported by Laupichler et al. [6], despite the exclusion of seven items from the original version. Nevertheless, further validation with larger and more diverse samples is needed to confirm its reliability and applicability.