Tools & Platforms

AI Can’t Gaslight Me if I Write by Hand

I drafted and revised this article in longhand, something I haven’t done since the mid-1990s, unless you count the occasional brainstorming I do in my journal. I made this choice because I’ve been worrying about how technology might be encroaching on my writing skills. I wanted to know what it would be like to return to the old ways.

I recognize that the overall loss of skills to technology is nothing new. After all, most of us don’t know how to hitch a horse to a wagon or spin yarn—although I’m interested in learning the latter. The world changes, and that’s okay. But in the digital age, innovation happens at lightning speed, with the results often integrated into our lives overnight—literally—and without our consent. That’s what happened when I woke up a week ago to find Microsoft Copilot, an AI writing assistant, installed on my computer—not as a separate app but as an integrated aspect of Microsoft Word. Its little grey icon hovered next to my cursor, prompting me to let it do my job for me. I spent an hour trying to get rid of it until I finally settled for turning it off.

I feel more and more that technology doesn’t liberate me as much as it diminishes me.

I value many technological innovations, such as the technology that enabled my laparoscopic surgery a few years ago. I think my Vita-mix is pretty darn nifty. And I’ve never doubted that the washing machine set us all free. But in recent years, I feel more and more that technology doesn’t liberate me as much as it diminishes me. Technological innovation has always had this darker side, slowly eating away at the things humans know how to do, or in the case of automation, the things humans get paid to do. But lately, the stakes feel higher. Where I used to feel new technologies robbed me of things I enjoyed doing, like driving a stick-shift car or operating my all-manual thirty-five millimeter camera, I now feel them getting into my head, interfering with the way I think, with my ability to process information. I worry: Am I forgetting how to add? How to spell? How to navigate the maze of streets in the metro area where I’ve lived for over forty years? Am I forgetting how to listen to and comprehend a film without subtitles, or how to read a novel?

That’s a lot of forgetting.

I have tried to resist many of these encroachments, tried to push back to preserve the skills that used to be rote, but I find it increasingly difficult. I feel my intellectual abilities slipping, despite myself, and I know: I am diminished. Now, technology is coming for my most valued skill, the one that has defined me since I first learned my letters: writing.

Of course, I am not alone in my fears about AI and how it might affect my profession as a writer and editor. We all have concerns about property infringement, the loss of jobs, the banality of ideas only formulated by the clunky cobbling together of what’s already been written and fed into the maw of the large language model (LLM). But I have an additional concern. For me, and for many like me, writing is not just a way of communicating, it’s a way of thinking. I rarely begin an essay with the entire thing planned out. Who does? Even if I have an outline, I will not yet have made all the connections that will come to be, let alone have planned out such things as metaphor, imagery, or other figures of speech that emerge in more creative pieces. Something about the state of suspension the brain enters while holding ideas in the air and doing the busywork of typing letters, spelling words, inserting punctuation into grammatically correct sentences, creates space where connections happen and ideas spring. It resembles the way a thing as simple as a person’s name will come to you when you let yourself think about something else. The physical act of writing serves as the distraction that lets the ideas flow. But also, and perhaps more importantly, writing forces the writer to think very slowly, only allowing the brain to move through an idea at the speed at which each individual word can be written. Perhaps that elongation of thinking gives the brain the time it needs to have new realizations. So much discovery happens as a piece of writing evolves that, like many writers, I often set out to write with the purpose of finding answers and prompting evolutions. In this way, writing itself functions as a generative act, a process of discovery and learning that far exceeds the simple recording and communicating of already formed ideas.

The physical act of writing serves as the distraction that lets the ideas flow.

Drafting this essay in longhand led me to think beyond how AI might affect this generative process to consider the other technological changes that have affected my writing over the course of my lifetime. Have those changes also impinged on writing’s process of discovery? I grew up with the unfolding of the digital age. In fact, I’m old enough to have begun writing my school papers with a pencil, reserving the pen for my final drafts. I remember the day when I decided to forgo the graphite and draft in ink. I had to adjust to the permanence of ink on the page when I’d yet to finalize—or sometimes even formulate—my thoughts. The typewriter came into the picture when my sixth-grade teacher required our class to turn in a typed final draft of our research papers. From then on, I typed all of my final drafts for school, progressing from a manual typewriter to an electronic one during high school and experimenting with various inadequate forms of whiteout in the process. I didn’t begin using a computerized word processor until college in the 1980s. And it was bliss! Anyone my age or older knows what a gift the invention of word processing felt like. The ability to add, delete, or rearrange text without having to retype entire pages just to correct one word was pure freedom. The composition on the page became so much more fluid, and the process of creating it so much faster.

But even then, I only used the computer as a glorified typewriter as I continued to compose all of my drafts by hand. It actually took years before it occurred to me to compose on the computer. During grad school, I wrote in longhand, typed up the draft, printed it out, edited it in hard copy, then typed the edits into my digital version, printed again, and repeated. However, when I found myself printing the same 25-page term paper multiple times to edit it, the wasted paper prompted me to consider editing straight on the computer. This process evolved until I finally decided to try composing there as well. Making the leap felt overwhelming because I did not yet know how to think about anything other than typing while typing. The integration of keyboarding into the already merged tasks of formulating ideas and composing grammatically correct sentences gave me the feeling of trying to fly without the proper means.

Of course, I adjusted. And soon I was flying. My fingers raced over the keyboard, enabling me to move through my ideas with a rapidity handwriting could never afford. Composing on the computer happens delightfully fast, but I wonder: if writing is a process of discovery and learning, then what discoveries did I lose by speeding up the process? What connections haven’t I made? Is there a level of richness or complexity I haven’t achieved because I’ve spent less time engaged in that magic writerly state of mind and therefore, less time exposed to the possibility of revelation? I can’t escape the thought that if slowness is key to writing, and writing is a way of thinking, perhaps each tech-driven acceleration of the process has chipped away at my depth of thought.

If writing is a process of discovery and learning, then what discoveries did I lose by speeding up the process?

Ironically, I found the return to hand writing an essay painfully slow at first. Although I eventually rediscovered my old routines, I initially had moments where I couldn’t wait to get to my computer so I could just get it down already—see the clean and neat print on the screen instead of my messy scratched up pages. I also noted that it took me forever to get started. I mulled over my ideas for weeks before putting pen to paper, in part because I felt a pressure to have all my thoughts together first. Before completing my first draft, I saw this delay as an impediment—thinking the prospect of writing by hand had held me up, slowed me down. Now, I see that prolonged period of contemplation as a benefit, providing another means of slowing down that gives the element of time its due, allowing it to generate and enrich ideas. This is why I always try to sleep on a draft before turning it in to a client, why taking a break from writing can help writers problem solve and iron out difficulties in a piece.

Writing is hard, so I see why some might be tempted to let a machine do the initial composing. The blank page represents the most difficult phase of writing because this is when the writer must engage with their topic most fully. In the absence of time or energy, AI might sound like a great solution—just as past innovations felt like godsends. But AI brings changes far more dramatic than those of the typewriter. If I let an LLM compose my first draft, only to edit and shape it and supposedly make it my own afterward—as I’ve heard some writers suggest—then I would have skipped over that initial composition process, that period of intense intellectual engagement through which we enrich our ideas. I would sacrifice the element of discovery, learning, and creation in favor of the LLM’s regurgitation. If the future offers a world filled with AI-produced prose, who knows how much we will collectively lose to writing created without all those unique incidents of epiphany and realization.

The idea that technology may have reduced the generation of ideas by speeding up my writing process came to me while working on this essay. I didn’t begin with that thought. I simply began with a question about how technological change had affected my writing. Answers came through my writing process. Realizing this, I decided to put the same question to ChatGPT. I used a few prompts: How has word processing changed how we write and influenced what we write? How has technology diminished my role as the driver of my own writing? The results were unremarkable. ChatGPT produced predictable answers (some of which I had already—predictably—mentioned). There were a few paragraphs about the speed of word processing and accessibility for those limited by poor spelling or grammar. It mentioned slightly off-topic items such as the effects of social media on writing. Interestingly, in response to the prompt about technology diminishing the writer’s role, it told me that too many AI suggestions might give the writer the “illusion” that the machine is directing the narrative more than the writer. Was AI gaslighting me?

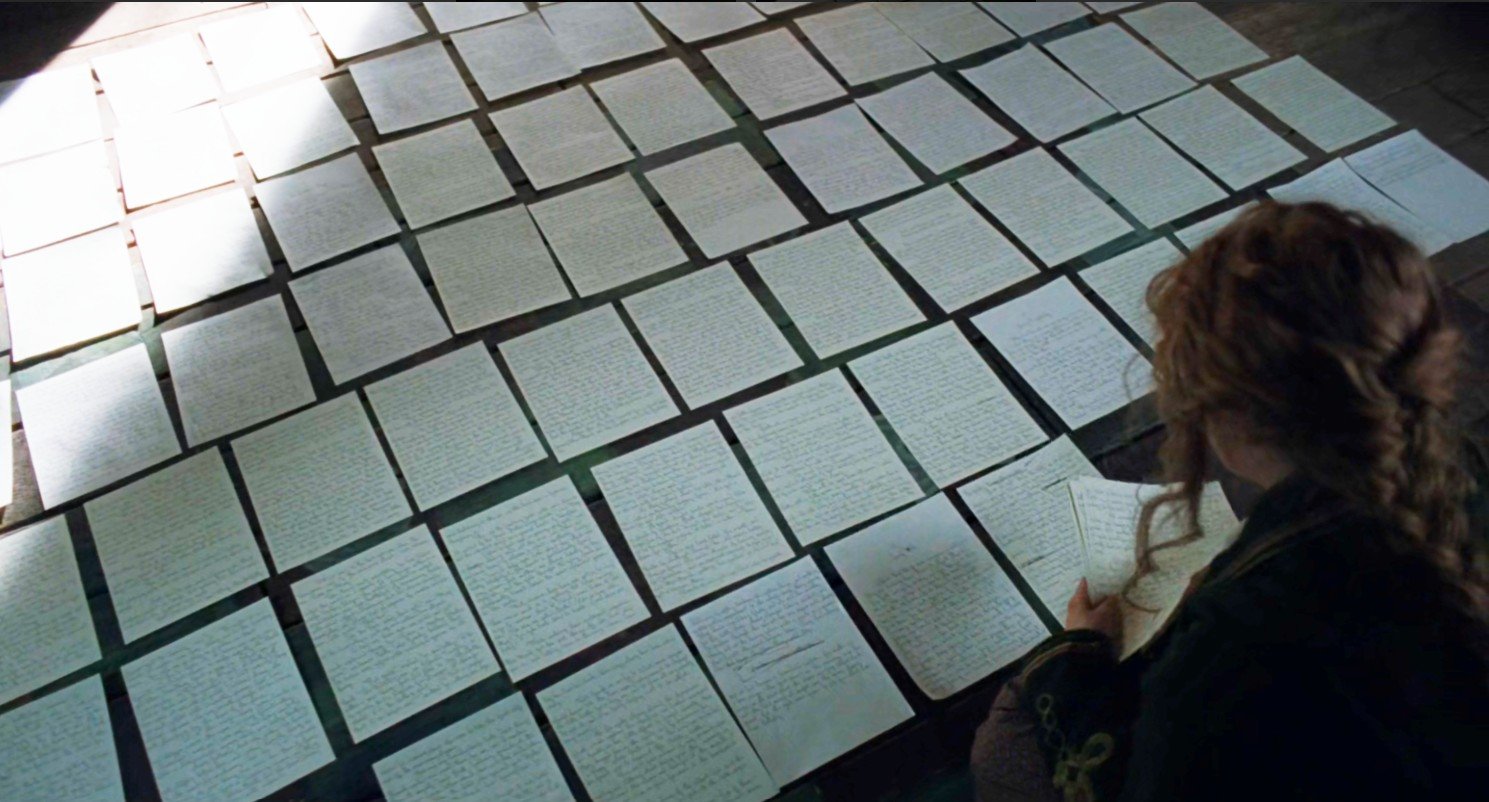

My essay certainly wouldn’t have evolved the same way if I’d begun writing by feeding those few prompts into an LLM. Who knows, maybe I would have ended up writing about social media? What I do know is that absorbing the results of the AI prompts didn’t feel like thinking, it felt like reading. If I’d started with AI-produced paragraphs, the generative process of writing the essay—not just the arrangement of ideas into sentences and paragraphs, but the process of formulating the actual points—would have come instantaneously from the outside. Meanwhile, I spent hours thinking about the topic before and after I started drafting and revising my handwritten essay. I experienced nostalgia remembering the satisfying clunk! clunk! of my old manual typewriter echoing in my childhood bedroom. I thought fondly of the long-ago graduate school days when I covered my living room floor with my term paper pages while trying to organize my thoughts. I pondered other questions, such as how AI might inhibit the development of voice for new writers only just coming of age. The paragraphs I wrote and cut about voice led to more paragraphs that were also cut about a job I had writing advertorials over a decade ago. I recognized the advertorial internet speak in the AI responses to my prompts. I even spent time thinking about the pleasure of improving my handwriting while drafting, relishing the curve of an “S,” the soaking of ink into the page as my pen looped through the script. These reflections don’t appear here—beyond their mention in this paragraph—but they are part of my experience of writing the essay, giving it more depth than any list of AI talking points. This experience demonstrates something basic, something I’ve known from years of journaling but didn’t think much about when I started this composition: writing is a personally enriching process, and it is this enrichment that comes across in the unique quality of what each of us writes. It is the soul of the writing, the thread that can connect writer to reader, which, I believe, is why we write in the first place.

There are all kinds of slow movements: slow food, slow families. Perhaps it’s time for slow writing.

Tech advancement has always asked us to relinquish our skills to machines in exchange for the reward of time. The deal feels worth it in many cases. But as I held my thick and crinkly sheaf of scribbled-on papers, it felt good and satisfying to have that physical product of my labor in my hands. And I wonder if perhaps we’ve gotten confused, thinking we should always use the extra time technology affords to do more things faster rather than using it to do fewer things slower. There are all kinds of slow movements: slow food, slow families. Perhaps it’s time for slow writing. For me, I plan to adjust my writing process by always writing my first draft on paper. This is, in part, an attempt to assert my humanity and wrest my writing from the clutches of technology, but it’s also a return to a process that feels good, takes time, and opens me more fully to the joys of personal discovery and connectedness that occur when words flow onto the page.

Tools & Platforms

Can the Middle East fight unauthorized AI-generated content with trustworthy tech? – Fast Company Middle East

Since its emergence a few years back, generative AI has been the center of controversy, from environmental concerns to deepfakes to the non-consensual use of data to train models. One of the most troubling issues has been deepfakes and voice cloning, which have affected everyone from celebrities to government officials.

In May, a deepfake video of Qatari Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani went viral. It appeared to show him criticizing US President Donald Trump after his Middle East tour and claiming he regretted inviting him. Keyframes from the clip were later traced back to a CBS 60 Minutes interview featuring the Emir in the same setting.

Most recently, YouTube drew backlash for another form of non-consensual AI use after revealing it had deployed AI-powered tools to “unblur, denoise, and improve clarity” on some uploaded content. The decision was made without the knowledge or consent of creators, and viewers were also unaware that the platform had intervened in the material.

In February, Microsoft disclosed that two US and four foreign developers had illegally accessed its generative AI services, reconfigured them to produce harmful content such as celebrity deepfakes, and resold the tools. According to a company blog post tied to its updated civil complaint, users created non-consensual intimate images and explicit material using modified versions of Azure OpenAI services. Microsoft also stated it deliberately excluded synthetic imagery and prompts from its filings to avoid further circulation of harmful content.

THE RISE OF FAKE CONTENT

Matin Jouzdani, Partner, Data Analytics & AI at KPMG Lower Gulf, says more and more content is being produced through AI, whether it’s commentary, images, or clips. “While fake or unauthorized content is nothing new, I’d say it’s gone to a new level. When browsing content, we increasingly ask, ‘Is that AI-generated?’ A concept that just a few years ago barely existed.”

Moussa Beidas, Partner and ideation lead at PwC Middle East, says the ease with which deepfakes can be created has become a major concern.

“A few years ago, a convincing deepfake required specialist skills and powerful hardware. Today, anyone with a phone can download an app and produce synthetic voices or images in minutes,” Beidas says. “That accessibility means the issue is far more visible, and it is touching not just public figures but ordinary people and businesses as well.”

Though regulatory frameworks are evolving, they still struggle to catch up to the speed of technical advances in the field. “The Middle East region faces the challenge of balancing technological innovation with ethical standards, mirroring a global issue where we see fraud attempts leveraging deepfakes increasing by a whopping 2137% across three years,” says Eliza Lozan, Partner, Privacy Governance & Compliance Leader at Deloitte Middle East.

Fabricated videos often lure users into clicking on malicious links that scam them out of money or install malware for broader system control, adds Lozan.

These challenges demand two key responses: organizations must adopt trustworthy AI frameworks, and individuals must be trained to detect deepfakes—an area where public awareness remains limited.

“To protect the wider public interest, Digital Ethics and the Fair Use of AI have been introduced and are now gaining serious traction among decision-makers in corporate and regulatory spaces,” Lozan says.

DEFINING CONSENT

Drawing on established regulatory frameworks, Lozan explains that “consent” is generally defined as obtaining explicit permission from individuals before collecting their data. It also clearly outlines the purpose of the collection—such as recording user commands to train cloud-based virtual assistants.

“The concept of proper ‘consent’ management can only be achieved on the back of a strong privacy culture within an organization and is contingent on privacy being baked into the system management lifecycle, as well as upskilling talent on the ethical use of AI,” she adds.

Before seeking consent, Lozan notes, individuals must be fully informed about why their data is being collected, who it will be shared with, how long it will be stored, any potential biases in the AI model, and the risks associated with its use.

Matt Cooke, cybersecurity strategist for EMEA at Proofpoint, echoes this: “We are all individuals, and own our appearance, personality, and voice. If someone will use those attributes to train AI to reproduce our likeness, we should always be asked for consent.”

There’s a gap between technology and regulation, and the pace of technological advancement has seemingly outstripped lawmakers’ ability to keep up.

While many ethically minded companies have implemented opt-in measures, Cooke says that “cybercriminals don’t operate with those levels of ethics and so we have to assume that our likeness will be used by criminals, perhaps with the intention of exploiting the trust of those within our relationship network.”

Beidas simplifies the concept further, noting that consent boils down to three essentials: people need to know what is happening, have a genuine choice, and be able to change their mind.

“If someone’s face, voice, or data is being used, the process should be clear and straightforward. That means plain language rather than technical jargon, and an easy way for individuals to opt out if they no longer feel comfortable,” he says.

TECHNOLOGY SAFEGUARDS

Still, the idea of establishing clear consent guidelines often seems far-fetched. While some leeway is given due to the technology’s relative newness, it is difficult to imagine systems capable of effectively moderating the sheer volume of content produced daily through generative AI, and this reality is echoed by industry leaders.

In May, speaking at an event promoting his new book, former UK deputy prime minister and ex-Meta executive Nick Clegg said that a push for artist consent would “basically kill” the AI industry overnight. He acknowledged that while the creative community should have the right to opt out of having their work used to train AI models, it is not feasible to obtain consent beforehand.

Michael Mosaad, Partner, Enterprise Security at Deloitte Middle East, highlights some practices being adopted for generative AI models.

“Although not a mandatory requirement, some Gen AI models now add watermarks to their generated text as best practice,” he explains.

“This means that, to prevent misuse, organizations are embedding recognizable signals into AI-generated content to make it traceable and protected without compromising its quality.”

Mosaad adds that organizations also voluntarily leverage AI to fight AI, using tools to prevent the misuse of generated content by limiting copying and inserting metadata into text.

Expanding on the range of tools being developed, Beidas says, “Some systems now attach content credentials, which act like a digital receipt showing when and where something was created. Others use invisible watermarks hidden in pixels or audio waves, detectable even after edits.”

“Platforms are also introducing their own labels for AI-generated material. None of these are perfect on their own, but layered together, they help people better judge what they see.”

GOVERNMENT AND PLATFORM REGULATIONS

Like technology safeguards, government and platform regulation are still in the air. However, their responsibility remains heavy, as individuals look to them to address online consent violations.

While platform policies are evolving, the challenge is speed. “Synthetic content can spread across different apps in seconds, while review processes often take much longer,” says Beidas. “The real opportunity lies in collaboration—governments, platforms, and the private sector working together on common standards such as watermarking and provenance, as well as faster response mechanisms. That is how we begin to close the gap between creation and enforcement.”

However, change is underway in countries such as Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, which are adopting AI regulations or guidelines, following the example of the European Union’s AI Act.

Since they are still in their early stages, Lozan says, “a gap persists in practically supporting organizations to understand and implement effective frameworks for identifying and managing risks when developing and deploying technologies like AI.”

According to Jouzdani, since the GCC already has a strong legal foundation protecting citizens from slander and discrimination, the same principles could be applied in AI-related cases.

“Regulators and lawmakers could take this a step further by ensuring that consent remains relevant not only to the initial use of content but also to subsequent uses, particularly on platforms beyond immediate jurisdiction,” he says, adding the need to strengthen online enforcement, especially when users remain anonymous or hidden.

Tools & Platforms

Exploring AI Agents’ Implementation in Enterprise and Financial Scenarios

Recently, the “Opinions on Deeply Implementing the ‘Artificial Intelligence +’ Initiative” issued by the State Council clearly stated that by 2027, the penetration rate of new – generation intelligent terminals and AI agents should exceed 70%, marking that the “AI agent economy” has entered an accelerated implementation phase. Against this policy background, the 3rd China AI Agent Annual Conference will be held in Shanghai on November 21st. The conference, themed “Initiating a New Intelligent Journey”, is hosted by MetaverseFamily. It focuses on two core tracks: enterprise – level and financial AI agents, bringing together the forces from upstream and downstream of the industrial chain to solve the pain points in the implementation of agent technologies and promote the effective implementation of the “Artificial Intelligence +” policy.

Two Core Segments Drive to Create a “Benchmark Platform” for Industry Exchange

As an important industry event after the implementation of the “Artificial Intelligence +” policy, this conference takes “practicality” and “precision” as its core. Through the form of “setting the tone at the main forum + solving problems at sub – forums + empowering through special sessions”, it provides participants with all – dimensional communication opportunities.

The Main Forum Focuses on AI Agent Trends and Determines the Technological Direction: In the morning, industry experts will discuss “the latest development and future opportunities of AI agents”, deeply analyze three technological paths: multimodal fusion, tool enhancement, and memory upgrade. At the same time, in line with the requirements of the “Opinions”, they will explore how agents can be deeply integrated with six key sectors, providing direction for enterprise layout.

Sub – forums Target “Enterprise – level and Financial AI Agents” and Provide Practical Solutions: Two sub – forums are set up in the afternoon to precisely meet the needs of different fields. Among them, the sub – forum on “Enterprise – level AI Agents Driving Marketing and Business Transformation” will break down the practical methods of local deployment of agents and database construction, share cases of cost reduction through business process automation, and help enterprises transform technologies into actual benefits. The sub – forum on “Financial AI Agents Reshaping the Industry’s Future” focuses on topics such as the technical principle of the 7×24 “risk – control sentinel” and the upgrade of intelligent customer service driven by large models, providing references for financial institutions to balance innovation and compliance.

Strengthen Resource Matching

The conference also features in – depth breakdowns of over 10 benchmark cases, a fireside chat among agent leaders, an annual award ceremony, and over 15 technology demonstration and experience areas. Participants can experience up close the application of agents in scenarios such as contract review and risk – control interception, and connect with over 300 industry professionals.

Supported by High – level Decision – Makers and Covering the Entire Industrial Chain

This conference has attracted the core forces of the AI agent industrial chain. The participants are characterized by a “high – end” profile. According to statistics, 30% of the participants are enterprise chairmen/general managers, and 25% are management personnel, covering key departments such as planning, marketing, information technology, and business, which can directly promote the implementation of cooperation.

As the conference organizer, MetaverseFamily is a hub – type media platform in the AI and metaverse fields. It has rich industry resources and event experience, providing strong support for the effectiveness of the conference. So far, the platform has held over 20 offline AI and metaverse conferences and over 40 online events, covering over 100,000 industry practitioners and having over 20,000 high – quality private WeChat group members. At the same time, it has successfully facilitated over 20 business cooperations, including the investment promotion project in Nanjing Niushoushan, the metaverse business cooperation with Mobile Tmall, and the upgrade of the AI shopping experience in an outlet mall, which can effectively connect resources and promote cooperation for participants.

In addition to the core topics, the “2025 AI Agent Annual Award Ceremony” at the conference is also worth looking forward to. The winners of heavy – weight awards such as the “Top 10 AI Agent Influential Brands of 2025” and the “Model Award for Financial AI Agents” are about to be announced.

Contact Us

Zhi Shu: 159 0191 1431 Alex.gan@ccglobal.com.cn

(Event Registration)

Tools & Platforms

Fidelity touts renewed Wealthscape, but departs from the AI hype with low-key launch; it's 'part of the larger story, not necessarily the story,' company says – RIABiz

-

Business3 weeks ago

Business3 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms1 month ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers3 months ago

Jobs & Careers3 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Education3 months ago

Education3 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Funding & Business3 months ago

Funding & Business3 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries