Attempts at communicating what generative artificial intelligence (AI) is and what it does have produced a range of metaphors and analogies.

From a “black box” to “autocomplete on steroids”, a “parrot”, and even a pair of “sneakers”, the goal is to make the understanding of a complex piece of technology accessible by grounding it in everyday experiences – even if the resulting comparison is often oversimplified or misleading.

One increasingly widespread analogy describes generative AI as a “calculator for words”. Popularised in part by the chief executive of OpenAI, Sam Altman, the calculator comparison suggests that much like the familiar plastic objects we used to crunch numbers in maths class, the purpose of generative AI tools is to help us crunch large amounts of linguistic data.

The calculator analogy has been rightly criticised, because it can obscure the more troubling aspects of generative AI. Unlike chatbots, calculators don’t have built-in biases, they don’t make mistakes, and they don’t pose fundamental ethical dilemmas.

Yet there is also danger in dismissing this analogy altogether, given that at its core, generative AI tools are word calculators.

What matters, however, is not the object itself, but the practice of calculating. And calculations in generative AI tools are designed to mimic those that underpin everyday human language use.

Languages have hidden statistics

Most language users are only indirectly aware of the extent to which their interactions are the product of statistical calculations.

Think, for example, about the discomfort of hearing someone say “pepper and salt” rather than “salt and pepper”. Or the odd look you would get if you ordered “powerful tea” rather than “strong tea” at a cafe.

The rules that govern the way we select and order words, and many other sequences in language, come from the frequency of our social encounters with them. The more often you hear something said a certain way, the less viable any alternative will sound. Or rather, the less plausible any other calculated sequence will seem.

In linguistics, the vast field dedicated to the study of language, these sequences are known as “collocations”. They’re just one of many phenomena that show how humans calculate multiword patterns based on whether they “feel right” – whether they sound appropriate, natural and human.

Why chatbot output ‘feels right’

One of the central achievements of large language models (LLMs) – and therefore chatbots – is that they have managed to formalise this “feel right” factor in ways that now successfully deceive human intuition.

In fact, they are some of the most powerful collocation systems in the world.

By calculating statistical dependencies between tokens (be they words, symbols, or dots of color) inside an abstract space that maps their meanings and relations, AI produces sequences that at this point not only pass as human in the Turing test, but perhaps more unsettlingly, can get users to fall in love with them.

À lire aussi :

In a lonely world, widespread AI chatbots and ‘companions’ pose unique psychological risks

A major reason why these developments are possible has to do with the linguistic roots of generative AI, which are often buried in the narrative of the technology’s development. But AI tools are as much a product of computer science as they are of different branches of linguistics.

The ancestors of contemporary LLMs such as GPT-5 and Gemini are the Cold War-era machine translation tools, designed to translate Russian into English. With the development of linguistics under figures such as Noam Chomsky, however, the goal of such machines moved from simple translation to decoding the principles of natural (that is, human) language processing.

The process of LLM development happened in stages, starting from attempts to mechanise the “rules” (such as grammar) of languages, through statistical approaches that measured frequencies of word sequences based on limited data sets, and to current models that use neural networks to generate fluid language.

However, the underlying practice of calculating probabilities has remained the same. Although scale and form have immeasurably changed, contemporary AI tools are still statistical systems of pattern recognition.

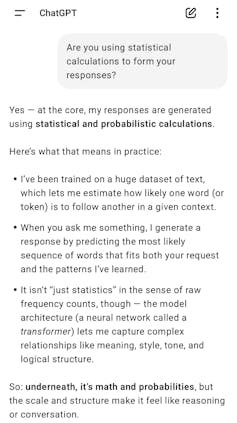

They are designed to calculate how we “language” about phenomena such as knowledge, behaviour or emotions, without direct access to any of these. If you prompt a chatbot such as ChatGPT to “reveal” this fact, it will readily oblige.

OpenAI/ChatGPT/The Conversation

AI is always just calculating

So why don’t we readily recognise this?

One major reason has to do with the way companies describe and name the practices of generative AI tools. Instead of “calculating”, generative AI tools are “thinking”, “reasoning”, “searching” or even “dreaming”.

The implication is that in cracking the equation for how humans use language patterns, generative AI has gained access to the values we transmit via language.

But at least for now, it has not.

It can calculate that “I” and “you” is most likely to collocate with “love”, but it is neither an “I” (it’s not a person), nor does it understand “love”, nor for that matter, you – the user writing the prompts.

Generative AI is always just calculating. And we should not mistake it for more.