Education

From gangs to college

LONG BEACH, Calif. — Lalo had almost put his pieces back together again, like a self-sufficient Humpty Dumpty. He’d gotten out of prison and moved into sober housing. He stopped responding to text messages from members of his gang. He went to a tattoo removal bar to have the ink in his face shattered into particles small enough for his immune system to break down. Lalo even got himself to Long Beach City College last year and told a woman in the registrar’s office that he hoped to become an addiction counselor. After enrolling in classes, he walked with her to the student center and was introduced to Jose Ibarra, the director of LBCC’s program for youth affected by gangs. Everything seemed to be coming together, and the sober housing his two roommates called hell — with its cheap linoleum flooring and showers separated by thin curtains — seemed to Lalo a land of promise.

Until, standing in one of the building’s colorless hallways, Lalo learned from the house manager that he was approaching the maximum number of days allowed and had just over 20 left to find somewhere else to live. He had no way to pay rent. He couldn’t move in with his parents because they lived in someone else’s garage. As Lalo focused on his classwork, the days ticked down to single digits. And that’s how, last September, Lalo found himself sitting on the edge of his metal-springed bed, or at least the bed that used to be his, head bent into hands.

Then Lalo remembered the playground in East Los Angeles with a fake castle. A slide joined with the castle’s roof to produce a concealed, dry space to sleep. He’d stayed there before.

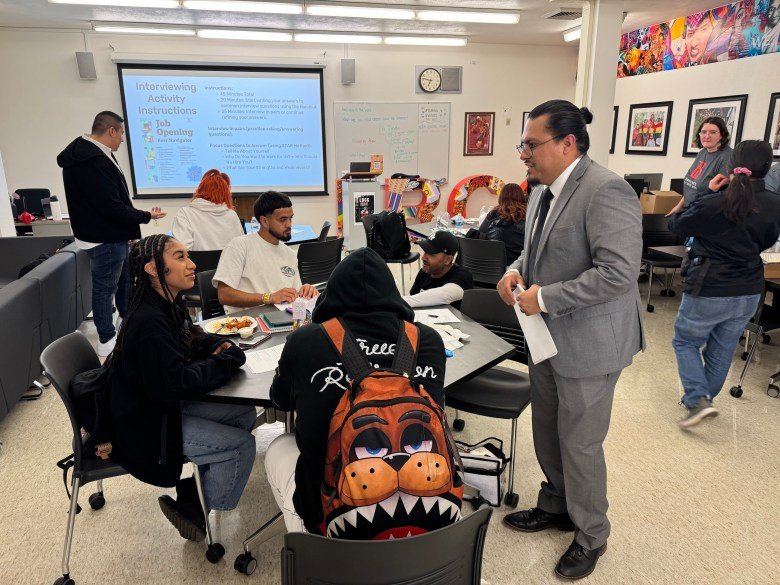

Lalo would have again, if it weren’t for the Phoenix Scholars program LBCC created in 2022, when it received the first award under the federal government’s Transitioning Gang-Involved Youth to Higher Education Program (TGIY). During the three-year term of the grant, Phoenix Scholars served 180 students, a combination of LBCC students who had a history with gangs and gang-involved teens recruited to be students. The grant expired just after President Donald Trump took office. Until then, the program served as a point-of-service for basic needs like food, and less basic ones like laptops, in addition to providing academic counseling, mentoring, mental health treatment, internship connections, work-study placements, interactive workshops and more. Unlike similar programs targeting all low-income students, Phoenix Scholars used an exceptionally low ratio — ranging from 10 to 24 students per staff member — to implement a high-touch, intrusive model. Translation: Staff had a low enough caseload to keep close tabs on students and be pushy, intervening before it was too late.

Related: Interested in more news about colleges and universities? Subscribe to our free biweekly higher education newsletter.

To date, 85 percent of students involved with Phoenix Scholars have stuck it out, term after term, compared to around 60 percent across the college. LBCC professors report that the students excel in class, attending regularly and engaging deeply. Three years in, 39 have completed a degree and transferred, and more are poised to transfer out of LBCC in less than three years, faster than the state average. Jaime Ramirez, 22, who is now a criminal justice major at California State University, Los Angeles, said he is a different person on the other side of the program. There’s also Karla Ramirez, 21 (no relation), who is majoring in anthropology and minoring in medical humanities at the University of California, Irvine. “I really struggled with asking for help,” she said, “but being part of these people … really showed me it’s OK.”

This degree of success is rare for a student-support initiative, and it owes to the program’s employment of “credible messengers,” like its director, Ibarra, which is to say, people who’ve lived it and get it. As a tween, Ibarra was regularly escorted by friends of his older sister, who was in a gang, and their AK-47s. He had been next up to join when his cousins, gang members just released from prison, were attacked at a party. One died and the other became paraplegic. So Ibarra focused on studying instead.

Only a few weeks into his first term, Lalo wouldn’t have told Ibarra about his eviction, except that one day the 24-year-old had seen the director’s sleeve creep up to reveal tattoos dancing along a forearm as caramel-toned as his own. On another, Ibarra shared that he too had struggled with addiction. The older man’s transparency about common experiences is why Lalo confided. Ibarra found money for a few nights at a motel, giving Lalo’s mom the time she needed to rent an apartment for the whole family. And just like that, the threat — of the playground, a relapse, dropping out of school — faded away.

For a time.

Figuring out just how many Lalos there are isn’t easy. Still, about 25 years ago, government surveys of youth and law enforcement data allowed for a general idea. Researchers placed the rate of lifetime gang membership between 4.8 percent and 8 percent nationally, which worked out to around 1 million actively involved juveniles. Thanks to an “erase the gang database” campaign and a decrease in federal investment in tools to gather systematic information on gangs, newer analyses have to rely on alternative data. David Pyrooz, a University of Colorado Boulder sociology professor, recently landed at 2 percent to 6.2 percent lifetime membership, which suggests around the same number of Americans have gotten involved in gangs as in the military.

According to additional research by Pyrooz, about 80 percent of youth complete high school, while fewer than half of those who join a gang do. That 30 percent gap owes to some obvious hurdles: Gangs encourage risky behavior that is also time-consuming. Their social milieu lacks academic role models and connections, and in it, investment in schooling is seen as unnecessary, uncool and even suspect. Other roadblocks to college enrollment are more hidden: High school staff often treat students they suspect of gang involvement differently, tracking them into classes that leave them unprepared to matriculate and counseling them out of applying to four-year colleges, research shows. Gang-involved teens usually don’t know financial aid is available and haven’t had key processes explained, like how to apply and the difference between a for-profit college, a trade school and Yale. Misinformation and mistreatment compounds so that gang-involved youth regularly develop a Pavlovian rejection of schooling.

As a result, those who participate in a gang complete 11.5 years of school, on average, compared to 13.6 years for everyone else, in one study. It’s a relatively small difference, but often a categorical one: high school diploma, no high school diploma. Still, gang-involved individuals are no less likely to eventually attend college than those living under similar socioeconomic conditions who avoid gang membership. These seemingly contradictory facts are both true, because gang involvement often functions as an interruption in schooling, not a hard stop. Still, people like Lalo are far less likely to graduate from college: Only 5.4 percent of those who have been gang members earn a four-year degree by their mid-20s, making them 58 percent less likely to do so than their matched counterparts. More hurdles are to blame: Some have to rebuff pressure to expand illicit activities into a new market. On many campuses, their older age and rougher past isolate them from other students. Both post-traumatic stress disorder and shame can pose ongoing difficulty, leaving these youth wary of revealing their needs.

Adrián Huerta, an associate professor at the USC Rossier School of Education and Keck School of Medicine grew up in a community like Lalo’s, where drug paraphernalia punctuated conversations and bushes.

One of Huerta’s dad’s best friends was incarcerated because of gang-related activity, and many of his own buddies joined in middle and high school. Huerta got suspended at their sides, but “by the grace of many mentors,” including a school security guard who insisted that Huerta do something different with his life, ended up in college. As he completed a bachelor of science, a master’s and a doctorate, Huerta kept thinking about the peers that others saw as boogeymen but whom he remembered as smart and equipped to excel. In paper after paper, he described gang-involved teens’ high hopes for higher education and sketched out a series of interventions in answer to the question: “How do we build trust with students who have been burned by everyone?”

Then, sitting at his desk one day in 2021, Huerta received what appeared to be a run-of-the-mill email from a colleague. He opened it to learn that the federal government was requesting applications for a new grant for programs directly serving gang-involved youth ages 14 to 24 under the Education Department’s Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education. “Oh my God,” Huerta thought. “Oh my God.” It was as if he’d spent years tinkering with the script for a movie he never expected to get made, only to have a producer come calling.

Pretty much immediately, Huerta thought of Long Beach City College. Residents of Long Beach tend to hail from one of two versions of the city: VisitLongBeach.com emphasizes the sunsets of “a waterfront playground,” while Reddit users will find a map apportioning city blocks to the East Side Longos 13, Asian Boyz, E/S Rollin 20s Neighborhoods Crips, West Side Islanders 33rd, Sons of Samoa Gangster Crips and more. Presumably in deference to the contrast, city officials chose the motto “Building a Better Long Beach.” LBCC uses the tagline, “You BeLong,” and Huerta knew the school’s president to be 100 percent committed to boosting students’ sense of “mattering,” a psychology term that refers to feeling valued and like you can add value to others.

The professor floated the idea of applying for the federal grant. The college president said, “Game on.” But one more administrator was needed to operationalize the chain of knowledge and support that would later extend from Huerta to Ibarra to Lalo and the 179 other adolescents whose lives were touched by the Phoenix Scholars program. Sonia De La Torre-Iniguez, LBCC’s dean of student equity, became giddy when she learned the school would receive $990,000 over three years to implement Huerta’s ideas.

“So often in higher education, we hear about theories and frameworks and models that are proposed, but there’s very little opportunity for practitioners to actually try those on,” De La Torre-Iniguez said.

LBCC got to.

For a time.

Related: ‘Revolutionary’ housing: How colleges aim to support formerly incarcerated students

By fourth grade, Lalo would stay out past 11 most nights. His mom got home from her second job just before midnight, and his dad was usually stretched on the couch, drunk, unconscious or both. Lalo didn’t like being on the streets so much, but he also didn’t like being inside the one-bedroom apartment he shared with seven others, especially because that’s where he’d witnessed his mom being physically abused. School was his happy place, but happy places are graded on a curve as much as students are, and there too Lalo found dysfunction and violence. In the classroom, he was used to great test scores, peers laughing at his jokes and teachers’ faces lighting with affection, but in the halls and on the tetherball court, Lalo’s emotions boiled up and sent his limbs flying at other kids. Tired of being in trouble, he started to ditch class in fifth grade in favor of drinking, smoking and writing on walls. And yet, each time adults asked him if he wanted to join their gang, Lalo said no.

Until the day he said yes.

The details are forever corroded by alcohol, but Lalo remembers two bald men ordering a group of teens to beat him when he was 12. When he returned home bloody and broken, his mom called the police, but Lalo refused to talk. He knew the stakes. If he didn’t join then, he’d be targeted for further abuse along with his siblings and parents. So Lalo gave in to the part of him that wanted that life anyway. He wanted the money. He wanted to feel powerful and secure, not small like he did when his new teacher’s stern words unmoored him. Lalo thought he was joining a brotherhood of people that would hold him up with a constancy he’d seen only on TV.

But as he began to rack up convictions — assault, burglary, vandalism, criminal threats — life only felt more unstable. The longer Lalo was away at juvie, the harder it was to go back to high school and sit next to perfect teens with their perfect folders. He wanted things to be different but felt stuck. Lalo was hurting himself, but he had to be drunk and high to hurt others, and he had to hurt others to hold onto the affiliation that was all he had. After he went to prison for abusing the mother of his 3-month-old baby in a rage, Lalo learned more about the gang’s hierarchy and practices. He realized that no one from his gang was visiting his parents while he was away. No one was checking in on his daughter or her mother. At 22, Lalo started to suspect that he’d been a puppet all along, that the gang he’d seen as a family for a decade had never been more than a series of transactions.

So when he got out, Lalo ignored texts from old homies asking him to “pull up,” thinking the apartment his mother had found was far enough from their old neighborhood to do that safely. Thanks to Ibarra’s help, Lalo was back on track and cruising through the fall 2024 term, even taking a scooter to apply for a job a few towns over, where he didn’t know anyone. But someone must have known him, maybe a member of a rival gang, maybe one of his own. Lalo couldn’t see the person’s face — people’s faces? — as he was dragged off the electric scooter and pummeled with a baseball bat. When he woke up, with EMTs surrounding him, Lalo called his mom and said, “Ama me quebraron la cara.”

Mom, they broke my face.

Because of that incident, and many others, Lalo asked to be identified by his nickname in this story.

The Phoenix Scholars program negotiated an excused withdrawal while Lalo recuperated and tried to process this bit of twisted karma. He had been unfailingly kind for years by that point, but women still tightened their grips on their purses and security guards still trailed him inside Walmart, not seeing the round cheeks and twinkling eyes amid his remaining tattoos. Lalo felt rejected and dejected, but he believed he only had himself to blame. He acted ruthlessly, so he should pay for his sins, but also how many months should each sin cost? When would his penance be done?

Though physically healed, Lalo didn’t sign up for winter classes. After the team noticed and badgered him, he enrolled. With guidance from Phoenix Scholars staff, he changed majors from psychology to human services addiction studies. Because of them, “whether it’s food, clothes, school supplies, a shower or shelter,” he said, “I’ve been a lot better mentally and emotionally.” With that support plus a program at LBCC for formerly incarcerated students, Lalo is now sure he’ll transfer to a four-year college. “I always wanted to be a part of a club like this, always,” he said, “I never did anything extracurricular in high school.”

Lalo often thinks about what he’ll tell his daughter, now age 6, when she asks about his past. He’ll try to describe how he felt like a fly stuck in a spider’s web. And then he’ll explain how one program could possibly have meant so much: “When you see somebody that comes from the same city, the same circumstances and almost the same skin tone as you, make it out,” Lalo said, “I don’t know — it does something to you.” Plus, “these people here are angels,” he said.

Related: From prison to dean’s list: How Danielle Metz got an education after incarceration

In February, the dean, De La Torre-Iniguez, sat at a conference table with professor Huerta as the Phoenix Scholars program entered its death throes. With the grant’s three-year term over, the money stopped coming in January, and it seemed unlikely more of it would flow toward LBCC’s gang-involved students in Trump’s new world order.

“We did a good job,” Huerta said, a proud dad stiffening his upper lip at his son’s wake. He turned toward De La Torre-Iniguez before carrying on. In bits and pieces, the two reminisced about how they’d decided an effective gang-to-college pipeline would require five elements: outreach, help matriculating, orientation, persistence support (in the form of trust-building and holistic wraparound services) and post-completion assistance.

They knew outreach would require more than slapping up some flyers, and sought out Ibarra, who had sat at the bedsides of gunshot victims, trying to talk them into leaving gang life. Later, he worked on gang reduction for the Los Angeles mayor’s office. After being named director of the fledgling Phoenix Scholars program in March 2022, Ibarra recruited participants by showing up at the right parks, community fairs and high schools. All the adolescents had to do was scan a QR code and fill out a quick intake form.

At orientation spread over three days, credible messengers like him communicated two messages in ringing tension: “You belong here,” and, “The way you engage in the street is not going to work here.”

Huerta walked a similarly thin line at a second type of orientation: 90-minute Zoom sessions he led for LBCC faculty and staff. They needed to understand the horrors students affected by gangs had faced without seeing them as victims devoid of agency. And they had to feel empathy without being drawn into a deficit mindset, since those same horrors had also fostered strengths.

With similar finesse, Huerta, De La Torre-Iniguez and Ibarra defined eligibility. The trio, who met every two weeks for over a year and then monthly, worried that limiting participation to gang-involved students would make the program so small that being associated with Phoenix Scholars would become a label, and a stigmatizing, unsafe one at that. As Huerta put it, “People are going to assume all these things that you did or didn’t do or whatever.” So they extended the program to “family-impacted” individuals, like Edrick Salgado, 22.

He never joined a gang because he saw what that lifestyle had done to his brother. When Salgado was 7, he was the one who found the 17-year-old, who had died by suicide. Without the Phoenix Scholars program, Salgado said, “I probably would have given up.” But each time the sociology major tried to leave LBCC, they were at him again, texting and even showing up at his workplace. Salgado has now completed 34 units and is on track to earn his associate degree for transfer in sociology by spring 2026. Last fall, he earned two A’s and a B, and spring term Salgado got all A’s.

“Community-impacted” individuals like Jessica Flores, a sunny, bouncy 19-year-old from South Central Los Angeles, round out the group, with a single screening question for that category: “Do you think it’s normal for you to hear gunshots at night?”

Eighty-three percent of the Phoenix Scholars would be the first in their family to graduate college, with 17 percent reporting that their parents didn’t finish high school. Even more, 89 percent, are economically disadvantaged. Only two said they remained active in a gang while participating in the program, but staff estimate that 30 percent of participants, over 50 students, once were gang-involved. That ratio makes sense given research showing that gang membership is often a form of identity exploration. Most gang members are affiliated for two years or less with more than 90 percent disengaging before adulthood. The murkiness reflected in these statistics is another reason Huerta said the program should include students who had been affected by gang activity even if they never formally joined.

So together, these students were served by Ibarra’s intrusive case-management team that included a dedicated academic counselor, two student success coaches and a wellness coach, all themselves students studying counseling or social work while working for Phoenix Scholars part-time.

For a time.

Related: Suspended for ‘other’: When states don’t share why kids are being kicked out of school

“Are you OK?”

“What’s going on?”

“Talk to us.”

“Did you do it?”

“Did you do it?”

These are a few of the texts that Flores remembers receiving from the Phoenix Scholars program. “You can never forget something,” she said: “If they’re aware of it, you best believe they’re going to talk about it every time they see you.” But Flores’ conviction and crisp diction tapered into the quiet tones of hopelessness as she described her family’s recent eviction. All of a sudden, she woke up not knowing if she’d earn enough to eat, like 64 percent of California’s community college students. Still, up until the graphing calculator incident, she was determined to excel this spring term.

Flores remembered returning the borrowed device on the last day of winter term, but since the office that loaned it to her didn’t have a record of that, the person at the desk refused to release a new one. Or the textbook she needed for psychology. Things got heated. “They were just like, talking mess to me,” Flores said. Feeling like she was being called a liar, she dropped her classes, thinking, “If I can’t pay for the books, I might as well.” The homelessness, the food insecurity, the argument — and the headaches that were her nervous system’s response to it all — felt insurmountable. But when Flores told Phoenix Scholars staff she’d dropped out, they helped her get another calculator, the textbook and four out of her five classes back. “They figured it out within 10 minutes,” she said. “They changed my life within 10 minutes.”

Now she plans to go to medical school. She’s always wanted to work in health care as a medical assistant or X-ray tech, but having watched student success coaches — those “near-peer” case managers — get graduate degrees and go on to their chosen careers despite prolonged flirtation with the poverty line, Flores decided she could be a surgeon. It was like being inspired by a successful big sister, she said. That word choice is intentional. She calls Ibarra “Papa.”

Family, specifically a tight, relentlessly supportive family, is what Lalo and others like him hope gangs will provide. The word “familia” is used not just for the criminal organization known as Nuestra Familia but by other gangs adopting the same descriptor in lowercase. All of which is to say, thanks to full institutional buy-in to offering comprehensive, longitudinal support from connected, credible messengers, students from gang-riddled communities who had long been searching for a safe place to lay their loyalty found it in LBCC’s Phoenix Scholars program.

Related: To support underserved students, four-year universities offer two-year associate degrees

At the program’s unofficial funeral in February, De La Torre-Iniguez had trouble squaring her natural enthusiasm with fiscal reality. They couldn’t afford to pay Ibarra to be director anymore and had reduced the program’s staff from five people to three, and yet she mused about replicating Phoenix Scholars at every community college in the state. Like Robin Williams and the Lost Boys imagining food until it appears in “Hook,” Huerta and Ibarra got in on the act. A house for the students! Child care too! They could do away with the age cap imposed by the federal grant. (If Lalo’s birthday had been even two months earlier, he would have turned 25 too soon to participate.) And why not develop a dual-enrollment track, rather than requiring a full class load, to hook students the same way many gangs had: with a little taste that gets them coming back for more? Huerta could even run a randomized trial, since the program had gotten so popular they’d had to turn students away!

They quickly remembered themselves. A nonprofit called Centro CHA had provided stipends for students, and the program also got support from the LBCC Foundation and the city of Long Beach. But the annual $330,000 from the TGIY program covered the vast majority of expenses.

That federal initiative had ramped up from just one award in 2021 to five in 2023, distributing more than $12 million total to 13 applicants between 2021 and 2024. Award recipients included partnerships involving colleges such as Allan Hancock College, Austin Community College and Richard J. Daley College as well as a bar association, a nonprofit focused on violence reduction and more. LBCC applied for another cycle of the federal grant last fall. Not getting it was disappointing, but still there was hope that a different type of grant could support their program until the Trump administration initiated a gutting reduction in force at the Department of Education. With about half the number of employees the department had in January, a judge recently concluded: “A department without enough employees to perform statutorily mandated functions is not a department at all.” Indeed, staff there have stopped responding to emails and calls about the future of TGIY. It is unclear whether current TGIY awardees continue to receive the promised funds and whether new ones will be chosen for FY 2025.

De La Torre-Iniguez made a plea through LBCC’s annual budgeting process to keep Phoenix Scholars for current participants and institutionalize pieces of the program going forward, but LBCC won’t be able to support a robust version of it without external funding.

“Maybe private foundations will step up and fill the gaps,” Huerta tossed out, yet chased his optimism with a sigh: “I’m sure the competition for private grants is going to get even more competitive.”

The magical food continued to shrink, until it disappeared from their table.

Related: OPINION: Our college students are struggling emotionally. We need to understand how to help them

When Huerta visited LBCC’s student center one day this spring, Lalo didn’t introduce himself right away. He stood off to the side as Huerta addressed a circle of Phoenix Scholars participants, defending the program’s nearly $1 million price tag for a few dozen graduates, and only some of them gang members at that. “It’s low-cost compared to gang-suppression units,” Huerta said, doing a little back-of-the-envelope math: “If there’s a shooting in Long Beach, it costs over $1 million per shooting, right? And if we help prevent 10 shootings over three years, that’s $10 million that we saved the city.” Looking at it another way, “it was like $5,000 … to support a student, and it’s what, $30,000 to incarcerate people?” He was only counting the program’s direct impact, but Lalo tells his nieces and nephews that if he can do it, they can too, and Flores said a handful of girls affiliated with a gang recently approached her: “They were like, ‘Oh my God, Jessica, how do you do this? Can you show me?’”

After the throng dwindled, Lalo stepped toward Huerta with the same mix of confidence and fragility that marked his living situation, sobriety and educational path, as well as his attempts to help his daughter get to know him with little gifts.

“How was your first semester?” Huerta asked.

“My first semester was honestly very pleasing,” Lalo said, referring to the term he completed before the attack. “I was very amazed at how much I learned in just eight weeks.”

What interested him the most, Huerta wanted to know. Minutes passed as the two discussed the field of addiction science, iterating on the pros and cons of contrasting approaches.

Then Huerta turned to the young man whose road had diverged from his own and said, “Hit me up, and I’ll connect you to the right people.”

That is how the gang-impacted students at LBCC, and all the schools that could have replicated its model, had the backing of the nation.

For a time.

Contact editor Nirvi Shah at 212-678-3445, securely on Signal at NirviShah.14 or via email at shah@hechingerreport.org.

This story about gang members was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

Education

For Good or Ill (or Both), College Students See AI as the Future

(TNS) — When incoming freshman Matt Cooper first set his eyes out for a coveted sousaphone position for the L row at The Ohio State University Marching Band, he prepared for auditions like anyone else would: practicing, playing, asking for help.

Except help came not from a coach, but from ChatGPT.

For many college students like Cooper, artificial intelligence has become a part of daily life.

This widespread everyday adoption marks a stark contrast from even a couple years ago, though: When OpenAI first introduced its chatbot to the public in 2022, the idea of AI in school settings ignited a heated debate on how the technology belonged in the classroom, if at all.

Just three years later, its adoption has spread rapidly. A recent nationwide study by Grammarly found that 87 percent of higher-ed students use AI for school, and 90 percent use it in daily life — spending 10 hours on average each week using AI. (Another study by the Digital Education Council had similar insights, finding that 86 percent of students around the world use AI for their studies.)

Yet colleges still have a patch quilt of standards for what constitutes acceptable AI use and what’s verboten. Across majors and universities in the U.S., Grammarly also discovered that while 78 percent of students say their schools have an AI policy, 32 percent say the policy is to not use AI. Nearly 46 percent of students said they worried about getting in trouble for using AI.

For instance, using AI to break down complex topics covered in class might be generally accepted, but using ChatGPT to edit an essay might raise some eyebrows.

Meanwhile, as students engage with the real world and consider their career options, they feel like they’re going to be left behind if they don’t develop AI expertise, especially as they complete internships, where they’re told as much to their faces. AI literacy has been called the most in-demand skill for workers in 2025.

That’s creating mixed emotions among college students, who are caught in between trying to follow two different sets of rules simultaneously.

To understand just how much AI has transformed young people’s lives, Fast Company reached out to undergraduates nationwide to find out how they’re navigating these conflicting mandates. What we found is that as the new technology continues to evolve, it’s carving a spot into the lives of college students — whether adults (or the students themselves) like it or not.

In this Premium story, you’ll learn:

- The creative ways Gen Z students are incorporating AI into their lives to become AI fluent, even if they can’t use it in their studies

- Why AI’s popularity as a coding assistant is starting to change how colleges think about AI in the classroom

- How current and recent students are striking a balance between “old school” and “new school” ways of learning

AN EVERYDAY COMPANION

As Ohio State’s Cooper practiced all summer for auditions, he found new ways to include technology into his life. “AI has actually helped a fairly decent amount with it, in ways that people wouldn’t normally expect,” he says.

From generating music sheets, or helping him memorize major scales and read key signatures, ChatGPT became Cooper’s trusted virtual coach. “In a matter of 20 seconds, it can come up with a full sheet of music to practice on any difficulty,” he says. (On top of that, the chatbot does it all for free.)

When Caitlin Conway, a senior at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, returned to school after a full-time internship in marketing, she found university life to be a bit of reverse culture shock after being out in the workforce. But she’s found easy-to-use chatbots like ChatGPT useful for adding more structure to her days.

“I found that you have so much time that sometimes you don’t really know what to do with it,” Conway says. “I use ChatGPT to make a schedule. Like: ‘I want to have this amount of time to do studying, to do my homework, and do a yoga class,’ and it’ll come up with an easy schedule for me to follow.”

Maliha Mahmud, a rising senior in business and advertising at the University of Florida, uses AI to streamline daily tasks outside of class. She’ll ask ChatGPT to craft a series of recipes with leftover ingredients in her fridge (as opposed to relying on instant ramen like generations of college kids before her). For school, Mahmud relies on AI as a sort of private instructor, willing to answer questions at any time. “I’ll tell AI to break a concept down to me as if they’re talking to a middle schooler to understand it more,” she says.

Many students also mentioned Google’s Notebook LM, an AI tool that helps analyze sources you upload, rather than searching the web for answers. Students can upload their notes, required readings, and journals to the platform, and ask Notebook LM to make custom audio summaries with human-like voices.

Still, the value of AI was oftentimes taught outside the classroom, in the workforce. Many students saying they were not only allowed, but encouraged to use AI during their internships. At her first internship at a tech PR company, New York University senior Anyka Chakravarty says that she felt that “to be a successful person, you need to become AI fluent, so there’s a tension there as well.”

Mahmud echoes Chakravarty’s experience. “During my internship, it was encouraged to be utilizing AI,” she says. “At first I thought it was a replacement, or that it was not letting us critically think. [But] it has been such a time saver.” Mahmud used Microsoft’s Copilot to automatically transcribe meetings, take notes, and send them to participants — tasks an intern would have done manually in the past.

All this is a far cry from how college students have been conditioned to think about AI as potential grounds for expulsion.

A CHECKERED PAST (AND PRESENT)

Today’s college generation was raised on plagiarism anxiety. Their pre-GPT world involved rechecking citations and resorting to online plagiarism checkers.

“I was just like, ‘I don’t want to touch this, because I don’t want to be ever accused of plagiarism.’ It definitely could be seen as very taboo,” says Grant Dutro, a recent economics and communications graduate from Wheaton College in Illinois.

Although more than half of students now use AI routinely, it wasn’t always welcomed with open arms — particularly for students who started college without it. Most students interviewed expressed an initial hesitation towards AI, because of that all-too-well known fear of getting flagged for plagiarism.

For decades, students were told that they could face severe repercussions for turning to the internet to download pre-written essays, copying material from books or blogs, and more. As technology advanced, so did the opportunities to plagiarize, particularly with the rise of services like TurnItIn, which flags copy-pasted and non-cited sources on essays.

Although colleges have managed to catch up with setting guidelines in place, the policies are oftentimes prohibitive, unclear, or left to the instructors. For many teachers, the AI policies in their classrooms are not universal, which is confusing for students and may even lead them to inadvertently getting in trouble.

For students whose policy falls to an instructor-by-instructor basis, this can sometimes mean that students taking the same course, but with different professors, could have vastly different experiences with AI, at least in the classroom.

“It’s morally incomprehensible to me that a large institution would not put front and center defining what their policies are, making sure they are consistent within departments,” says Jenny Maxwell, Grammarly’s head of education. “Because of the institution not being clear on their policy, their own students are being harmed because of that lack of communication,” Maxwell added.

While AI use in school appears to be steadily destigmatized among students, it certainly is in the workplace. Some students who recently completed internships said that not only were they allowed to use AI on the job, but were encouraged to do so (Sure enough, experts recommend recent grads upskill themselves in AI literacy, while one in three managers say they’ll refuse to hire candidates with no AI skills.)

A NEW WAY TO LEARN

The conflicting messages of “AI gets you in trouble” and “AI is the future” complicates the technology’s presence in college students’ lives, be it in class, on an internship, or in the dorm. But for many, it’s simply shifting what learning looks like.

For instance, the framework to evaluate students’s success might have depended on essays in the past. But today, it might be more suitable to judge both the essay and the process of writing with technology, Grammarly’s Maxwell says. Many students say that standards are changing to measure their learning already.

Claire Shaw, a former engineering student at the University of Toronto who graduated in 2024, explained that when she began college, she learned the basics of coding at the same time that AI piqued the interest of her instructors. She learned the “old school” way while being encouraged by some of her teachers to play with new technology. Still, Shaw did not start using AI for school until her fourth year. Now, she believes a balance between old school and new school can exist.

“You’re allowed to use AI tools, so the standard for those kinds of coding assignments were elevated,” Shaw says. It points to a big shift: In academia, where AI was (and in many cases, still does) feel taboo, it’s also being embraced, even in class.

But now that AI is now an expected tool, the difficulty of coding assignments has been elevated, she says, leading to more advanced projects at an earlier stage in a student’s career. And while this might be exciting, and a great prep for the future, Shaw still highlights the need to understand fundamentals — skills you learn on your own without AI’s help — before jumping in head first.

“There are certain moments where we still need to test the raw skills of somebody by setting up environments that don’t have AI tool access,” she explained, referencing in-person examinations with no AI tools available.

Think of it as learning to drive stick, while automatic cars exist — combining AI with traditional teaching methods may create a more holistic education. Similarly for humanities majors, some instructors are taking notes out of the old school playbook to measure these “raw skills,” like debating, communication, and critical thinking. “We’ve turned to doing a lot more interactive stuff, like doing discussion circles, or handwriting pieces of writing,” says NYU’s Chakravarty, who’s also a mentor in the school’s writing center.

College students know AI isn’t going anywhere. Even though everyone — students, teachers, schools, first bosses — continues to stumble their way through adoption, there will be some aspects of the college experience that may never go obsolete.

“My professors brought out blue books again,” says Chakravarty. “Which I hadn’t had since, like, my first semester.”

Fast Company © 2025 Mansueto Ventures, LLC. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Education

UK universities cut back on crucial research because of reduced funding | Research funding

Universities are cutting back on vital research, with world-leading work on deadly conditions such as cancer and heart disease under threat from an erosion in funding from government and charities, according to a report.

The report, compiled by Universities UK, found that one in five UK universities have reduced their research activity, including cuts to life sciences, medicine and environmental sciences, and many said they were expecting to make steeper cuts in the future because of mounting financial pressures.

Health charities are major funders of high-value medical and life sciences research – including areas such as oncology and dementia – but the report said universities “are backing away from charity-funded research” because of the additional costs involved.

Dan Hurley, Universities UK’s deputy director of policy, said: “There is a real need for us to work with funders and government to address some of the risks here and get under the skin of what this might look like.

“What we do know is that most charity funding is in the medical and health space, so it is definitely having an impact in that area.

“We can’t pinpoint the degree to which this is impacting specific disciplines but the findings in this report are a warning that really difficult decisions are being taken on the ground and if we want to maintain the UK’s international competitiveness when it comes to research then we need to go further to support it.

“While these headline findings are a strong warning in themselves, this is going to require ongoing monitoring.”

The report, done in collaboration with the Campaign for Science and Engineering and the Association of Research Managers and Administrators using surveys of academic researchers, found that “sustained financial constraints” were likely to diminish the estimated £54bn annual contribution made by university research to the UK economy.

The study found there had been a 4% decrease in research staff in the biological, mathematical and physical sciences in the last three years, while staff in medicine, dentistry and health have dropped by 2%, mainly in highly expensive clinical medicine.

after newsletter promotion

The funding difficulties were undermining university research culture, and managers reported an impact on morale and wellbeing, less participation in conferences and knowledge exchanges, and had particular concerns for early career researchers who were struggling to get the support they needed to establish networks.

One major reason was that UK government research funding awarded on the basis of departmental track records and quality has been severely eroded by inflation, while universities are less able to use international tuition fee income to subsidise research because of falling numbers of overseas students.

“Fluctuations in international recruitment and fees from international students will have an impact on research funding – because universities aren’t able to recoup the full economic cost of research, cross-subsidisation had become a feature of funding for many,” Hurley said.

The report concluded that the UK’s position as a global leader in research and innovation is under threat as research becomes too costly to sustain, and more universities are expected to make “tough decisions” on cuts in the future.

“Universities are doing everything they can to improve efficiencies and address those financial challenges. But what’s clear is that further efficiencies are not going to be enough on their own to address these broader risks to areas of research, with implications for our research system’s international competitiveness.

“So we also need action from the government on the future of quality-related funding, which hasn’t kept pace with inflation for a decade. That’s going to be critical to restoring stability to areas of research,” Hurley said.

The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology has been contacted for a response.

Education

ATS Breathe Easy – Lessons Learned from AI in Medical Education

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms1 month ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi