Education

Seiji Isotani’s Mission to Humanize AI in Education

Newswise — As Penn GSE expands its leadership in AI and education, newly hired associate professor Seiji Isotani adds a vital perspective shaped by decades of work in Brazil, Japan, and the United States.

A pioneer in intelligent tutoring systems, Isotani develops AI tools that adapt to the needs of students and teachers—especially in under-resourced settings. But for him, technology is never the starting point.

In this Q&A, he reflects on the childhood experience that launched his career, the importance of human-centered design, and why responsible AI must begin with understanding the people it’s meant to serve.

Q: What originally drew you to the field of educational technology?

A: Working with educational technology holds special meaning for me, inspired by a personal experience. As a child, I struggled in school. I couldn’t read or work with numbers at age 7, and some even thought I had a learning disability. Fortunately, my mom, a talented public school math teacher, and my dad, a professor at the University of São Paulo, worked with me every night until I caught up. Eventually, we discovered that my difficulties were due to issues with vision, communication, and hearing.

Once those were addressed, everything changed. I went from falling behind to becoming one of the top students, especially in STEM subjects.

That transformation lit a fire in me. I wanted to help others experience that same change, and I started to help other students with their struggles during class. When I got my first computer at age 11, I was instantly in love. I taught myself to program and quickly realized that I could use this technology to help other students learn in ways that worked for them. That spark led me to educational technology, and it still fuels my work today, particularly in one of my main research areas: intelligent tutoring systems.

Q: Your work explores the use of AI to improve learning. What’s one way you think AI could genuinely help students or teachers?

A: One of the most exciting ways AI can make a difference is by acting as a true partner for teachers, helping them do what they already do well or even improve their practices, but with more insight and support. By deeply understanding teachers’ needs (as explored in my recent study) and developing AI-powered tools like those in the MathAIde project, we’ve shown that even in resource-constrained environments, teachers can receive timely, actionable feedback about their students’ learning. They can use AI to plan lessons more efficiently and get personalized suggestions for tailoring activities to each learner’s needs.

At the same time, students benefit from more engaging and personalized learning experiences, including gamified elements that adapt to their interests and help keep them motivated (as evidenced in another study of mine). It’s not about replacing teachers or increasing students’ cognitive offload. It’s about giving both teachers and students “superpowers” so they can shine and show all their might.

Q: What drew you to join the faculty at Penn GSE?

A: Honestly, I couldn’t imagine a better place to do the work I care about. Penn GSE is a powerhouse when it comes to rethinking education through innovation. I’ve admired the school’s deep commitment to investing in the field of AI in Education to create real-world impact, especially in K–12 education.

The opportunity to contribute to and grow with Penn GSE, by helping build a strong program that not only trains the next generation of AI in education leaders but also shapes the global conversation on how AI can support more accessible and meaningful learning experiences, is incredibly exciting to me!

Penn is already leading the AI in education agenda across top universities in the U.S. and around the world, and the chance to be part of that movement is truly inspiring. After meeting the faculty and students, it became crystal clear to me: this is where I want to be to help change the world. I’m especially excited to collaborate with such a passionate and visionary community made up of people who, like me, are committed to making education more human, more engaging, and more inspiring through the thoughtful and responsible development and use of AI.

Q: You’ve worked in both Brazil and the U.S.—how have those experiences shaped your perspective on education and innovation?

A: Working in Brazil and the U.S. has certainly shaped my perspective, and adding to my journey, I’ve also had the opportunity to collaborate closely with researchers and schools in other countries, such as Japan, where I completed my doctoral studies. These experiences across very different educational systems and cultures have given me the flexibility to embrace multicultural environments, understand diverse classroom contexts, and navigate the complexities of working in both low- and high-income communities.

What I’ve learned is that challenges in education are not exclusive to any one region. Whether I am working in a rural school in the Amazon, an urban district in the U.S., or a high-tech classroom in Japan, I encounter students and teachers who struggle, whether due to lack of infrastructure, insufficient support, or systems that do not fully meet their needs. These shared struggles, though expressed differently across contexts, have helped me become more connected to what really matters: understanding people and their goals. This is why a human-centered approach is at the heart of my work. For me, it’s not just about gathering data or training AI models. It’s about what we can do with AI and data to help people learn better, teach better, and feel more empowered. Designing AI in education means listening deeply to communities, co-creating solutions with them, and ensuring that the tools we develop truly serve the people they are meant to support.

Q: What’s something surprising or lesser known about your research that you enjoy sharing with others?

A: One thing that often surprises people is that I tend to avoid starting my projects by advocating for the use of AI. Even though I’m deeply involved in AI in education, I actually try to avoid introducing AI at the beginning, especially when the goal is to improve public policy through technology.

In fact, when people ask me, “How can we use AI to improve education policy?”, my first response is usually a question: “Do you already have a shared vision for the kind of education you want in your country or community? Do you have an understanding of the needs of your teachers, principals, students, and families?”

If we can’t answer those questions clearly, it’s very hard to use AI effectively, because we don’t yet know why we need AI or how it should be developed or used to actually serve the people it’s intended to help.

Thus, whether I’m working with a ministry of education or a local school, I begin by engaging deeply with people on the ground. And sometimes, AI is not the silver bullet; in fact, it often isn’t. What tends to work best is not AI alone, but a thoughtful combination of AI with practices rooted in the learning sciences and well-established educational strategies (e.g., structured pedagogy). Nothing flashy, just what works.

Q: When you’re not thinking about research, how do you like to spend your time?

A: Outside of work, my favorite role is being a dad. Spending time with my 4-year-old son and 8-year-old daughter brings me so much joy. They constantly remind me that the true wonders of the world live in small discoveries, in the curiosity to learn about everything, and in the joy of sharing what you’ve learned with those you love.

I have also practiced Judo for about 35 years. In my early days, I trained professionally for competitions and was fortunate to win state and national championships a few times. Although I had to stop training during the pandemic and haven’t returned to a dojo since, I hope to resume my practice in Philadelphia. In the meantime, I still enjoy “training” and playing Judo with my kids at home.

Finally, I also love trying new foods, exploring different cultures, and occasionally watching anime, a fun reminder of my “otaku” days back when I lived in Japan.

Q: Are you more hopeful or cautious about the role of AI in education over the next decade—and what gives you that outlook?

A: You tell me. Just kidding! I’m definitely more hopeful, but in a grounded and thoughtful way. AI is already shaping our society, and it holds incredible potential to transform education for the better, especially when it’s designed responsibly with people and for people. I’ve seen what happens when we get it right: teachers feel empowered, students feel seen and supported, and learning becomes more meaningful, engaging, and joyful.

I have a strong sense that once we move past this initial wave of hype and the overemphasis on the technology itself, we will enter a new phase. That is when the real breakthroughs in AI for education will emerge, focused on truly serving educational needs and empowering communities.

Education

How to use ChatGPT at university without cheating: ‘Now it’s more like a study partner’ | University guide

For many students, ChatGPT has become as standard a tool as a notebook or a calculator.

Whether it’s tidying up grammar, organising revision notes, or generating flashcards, AI is fast becoming a go-to companion in university life. But as campuses scramble to keep pace with the technology, a line is being quietly drawn. Using it to understand? Fine. Using it to write your assignments? Not allowed.

According to a recent report from the Higher Education Policy Institute, almost 92% of students are now using generative AI in some form, a jump from 66% the previous year.

“Honestly, everyone is using it,” says Magan Chin, a master’s student in technology policy at Cambridge, who shares her favourite AI study hacks on TikTok, where tips range from chat-based study sessions to clever note-sifting prompts.

“It’s evolved. At first, people saw ChatGPT as cheating and [thought] that it was damaging our critical thinking skills. But now, it’s more like a study partner and a conversational tool to help us improve.”

It has even picked up a nickname: “People just call it ‘Chat’,” she says.

Used wisely, it can be a powerful self-study tool. Chin recommends giving it class notes and asking it to generate practice exam questions.

“You can have a verbal conversation like you would with a professor and you can interact with it,” she points out, adding that it can also make diagrams and summarise difficult topics.

Jayna Devani, the international education lead at ChatGPT’s US-based developer, OpenAI, recommends this kind of interaction. “You can upload course slides and ask for multiple-choice questions,” she says. “It helps you break down complex tasks into key steps and clarify concepts.”

Still, there is a risk of overreliance. Chin and her peers practise what they call the “pushback method”.

“When ChatGPT gives you an answer, think about what someone else might say in response,” she says. “Use it as an alternative perspective, but remember it’s just one voice among many.” She recommends asking how others might approach this differently.

That kind of positive use is often welcomed by universities. But academic communities are grappling with the issue of AI misuse and many lecturers have expressed grave concerns about the impact on the university experience.

Graham Wynn, pro-vice-chancellor for education at Northumbria University, says using it to support and structure assessments is permitted, but students should not rely on the knowledge and content of AI. “Students can quickly find themselves running into trouble with hallucinations, made-up references and fictitious content.”

Northumbria, like many universities, has AI detectors in place and can flag submissions where there is potential overreliance. At University of the Arts London (UAL) students are required to keep a log of their AI use to situate it in their individual creative process.

As with most emerging technologies, things are moving quickly. The AI tools students are using today are already common in the workplaces they will be entering tomorrow. But university is not just about the result, it is about the process and the message from educators is clear: let AI assist your learning, not replace it.

“AI literacy is a core skill for students,” says a UAL spokesperson, before adding: “Approach it with both curiosity and awareness.”

Education

‘I regret pushing my daughter into school until she broke’

Ben SchofieldPolitics correspondent, BBC East

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCThe start of the school year saw the Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson warn parents about the need for children to attend classes.

Data suggests half of pupils who missed lessons in the first week of term last year went on to become persistently absent.

But school leaders say they are seeing more children who find attending school too traumatic.

What is it like having a child with what psychologists call emotionally based school avoidance and what should be done to help?

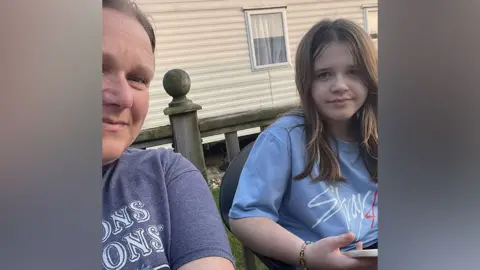

Family handout

Family handoutThe final time Julie took her daughter to school in July 2023, a member of staff congratulated her.

Rosie, who was then eight, was “wearing a dirty pyjama top, a pair of jogging bottoms, a pair of trainers with no socks, she had her headphones on, she was holding a teddy”, Julie recalls.

“I walked into school and the [special needs co-ordinator] then said to me ‘well done, you got her here’.”

But for Julie, 48, it was not a “win”.

“She couldn’t even speak, she hadn’t eaten, she had maybe three or four hours sleep.

“But I’d done a good job as a parent for making her go to school?”

Family handout

Family handoutAt the time Rosie, who has autism, was in Year Three at a primary school in Northamptonshire.

Julie says her daughter had struggled with the school environment since her time in nursery and is now educated out of school.

Rosie, she recalls, was “in fight and flight the whole time” she was in the classroom, which “just overwhelmed her”.

Eventually Rosie was “begging not to leave” the house for school and was self-harming, sometimes on the school run.

“She would have night terrors – she would be up screaming, if she went to sleep at all.

“It just felt as if I was walking her into the lion’s den every single day,” she says.

Meanwhile, Julie and her husband James received letters and home visits from school staff about Rosie’s attendance.

“It was very lonely.

“All of a sudden there’s these letters and people are talking about fines and I was lost.”

On that final say Julie says she “dragged” Rosie to school because “that was the expectation”.

Now she wishes she had taken Rosie out of school earlier.

“But I also feel that if I hadn’t have got to the point… where she broke, I would never have known if it had worked,” she says.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCBased on Rosie’s reaction to school, an educational psychologist who assessed her noted she had “emotionally based school avoidance” or EBSA, a condition school leaders say they are encountering more.

Anna Hewes, the head teacher of Prince William School, a 1,400-pupil secondary in Oundle, Northamptonshire, says schools are seeing a “big increase” in EBSA among pupils in Year Seven, Eight and Nine.

The transition to secondary school is, she adds, a “key time” and at the start of the school year EBSA is “at the forefront of our minds because of the new year sevens coming through”.

The “noises, the bustling nature of a school – the busyness, all the classes walking around” make it a “real challenge” for those with sensory needs, she says.

But more generally “it’s very tough to be a teenager these days”.

Smartphones and social media, she adds, mean “young people can’t escape anymore”.

“It definitely is a post-Covid spike and these young people are genuinely really struggling to step over the threshold of the school and sometimes leave their bedrooms.”

DJ McLaren/BBC

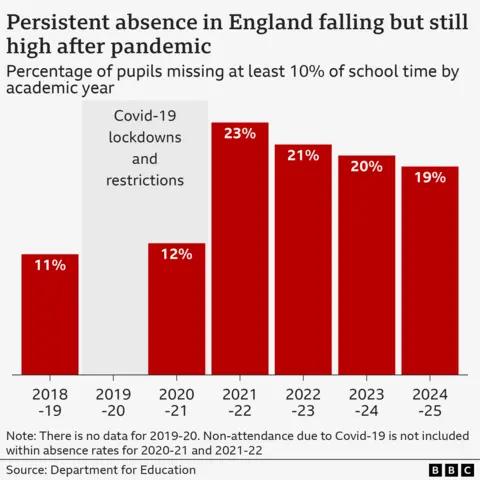

DJ McLaren/BBCAcross England, rates of “persistent absence” – when pupils miss 10% or more of lessons – have remained high since the pandemic.

Last academic year almost 19% of pupils were persistently absent, compared with 11% in 2018/19.

Mrs Hewes says EBSA is a “significant part” of the issue.

A lack of reliable data, however, means it is difficult to know how big a part.

Mrs Hewes says Prince William Academy prioritises “inclusion” and has recruited an assistant head teacher for “belonging”.

It has also opened a specialist “school-within-a-school” for pupils with EBSA, funded by North Northamptonshire Council. Four students have been enrolled so far and by 2028 it expects to see 48.

Jenny Nimmo, the head of inclusion at East Midlands Academy Trust, which runs Prince William Academy, says the unit will have more “homely” classrooms and on-site mental health provision.

She hopes it will be “future proof” because EBSA “isn’t going away”.

There are, she adds, “more and more young people” with “emotionally based school avoidance and indeed anxiety”.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCThe Compass Centre in Luton also help pupils with EBSA access education.

Dr Joanne Summers, Luton Borough Council’s principal educational psychologist, says the condition can appear suddenly but “when you look back, there has been anxiety around being in school” and one incident might be a “catalyst”.

Intervening early, she adds, is important, as falling behind on school work and losing contact with friends can make anxiety worse.

Dr Summers says Luton has been trying to move away from seeing school absences as “defiance and truancy”.

“We are being curious about what’s going on for that young person, why is it that they are behaving in this way,” she adds.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCGeoff Barton, a former head teacher in Suffolk and previous general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, says there should be more “emphasis on the humanity of our schools” rather than “draconian discipline” over absences.

He is researching special educational needs (Send) provision for the left-leaning think tank the Institute for Public Policy Research.

He says the people he is speaking to are “universally saying” that anxiety among pupils has increased.

But the “age of anxiety” is only one reason for persistent absence.

Another is poverty, while he says there is also a “long shadow in education of Covid” when “schools started to feel a bit more of an optional decision”.

Cornelia Andrecut, the executive director of children’s services for North Northamptonshire Council, said the authority has offered training courses for schools to learn strategies to support children with EBSA.

The government says it will spend £740m creating “more specialist places in mainstream schools” and placing Send leads in 1,000 new family hubs.

A Department for Education spokesperson says: “Schools should take a ‘support first’ approach for children who are facing barriers to regular school attendance, and we are expanding access to mental health support teams in all schools, ensuring that every pupil has access to early support services in their community.”

Family handout

Family handoutFor Julie, taking Rosie out of school was “not a lifestyle choice” but was prompted by “trauma and distress” that her daughter is still recovering from.

Does she regret pushing Rosie to attend school?

“Yeah – definitely.

“I always wonder if there was a bit of trust broken between us as mum and daughter when I still took her into that place when it was that bad.”

Education

Earl Richardson, who spotlighted HBCU funding disparities, dies : NPR

Earl Richardson was the president of Morgan State University between 1984 and 2010.

Morgan State University

hide caption

toggle caption

Morgan State University

Earl Richardson was a Black college president — “armed with history,” as a colleague described him — when he led a 15-year-long lawsuit that ended in a historic settlement for four Black schools in Maryland and put a spotlight on funding disparities for all of the nation’s historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

Richardson’s death, at 81, was announced on Saturday by Morgan State University, located in Baltimore, where he served as president when he helped organize the lawsuit that began in 2006. It was settled in 2021 when the state of Maryland agreed to give $577 million in supplemental funding over 10 years to four HBCUs.

Richardson led Morgan State from 1984 to 2010 and he had long chafed at stretching the little funding he got from the state. In the lawsuit, plaintiffs argued that Maryland had historically underfunded its Black colleges and had put them at a disadvantage by starting and boosting similar programs at nearby majority-white schools.

David Burton, one of the plaintiffs, told NPR that the case was compared to Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark lawsuit that brought up similar issues of disparities in educational opportunities for Black students, but the Maryland case raised the issues for students in higher education.

In 1990, when Richardson was a new school president, students took over the administration building for six days to protest the school’s dilapidated classrooms and dorms, with roofs that leaked and science labs stocked with outdated equipment.

Edwin Johnson was one of those student protesters. “We originally were protesting against Morgan’s administration,” including Richardson, he said. “But then after we dig and do a little research, we find out it’s not our administration, but it’s the governor down in Annapolis that isn’t equipping the administration with what they need to appropriately run the school.”

The protest ended when the students marched 34 miles to Annapolis to demand a meeting with the governor.

Richardson, who spoke of taking part in civil rights demonstrations when he was in school, had subtly guided the students to the correct target, said Johnson, who is now the university’s historian and special assistant to the provost.

That protest helped pave the way to the future, historic lawsuit.

Because Richardson was the university’s president, and an employee of the state, he couldn’t sue the state. So, a coalition of students and former students was created, the Coalition for Equity and Excellence in Maryland Higher Education Inc., to serve as the plaintiff.

Still, Richardson was the visionary behind the lawsuit, said Burton, a Morgan State alumnus and now a strategic planner for businesses. “He was armed with history,” Burton said.

“Dr. Richardson knew where the skeletons were,” Burton added. He was “a force that the state could not reckon with because of his institutional knowledge.”

At one point, during the trial, state attorneys objected to Richardson’s presence in the courtroom and asked the judge to make him leave, even though he had a right to be there as an expert witness, said Jon Greenbaum, then the chief counsel of the Lawyer’s Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, who helped argue the lawsuit.

Richardson stayed in the courtroom and “because this was really a desegregation case,” said Greenbaum, he provided historical detail that became critical to the arguments made by the lawyers representing the plaintiffs.

The funding that resulted, and Richardson’s leadership, jump-started what is now called on campus “Morgan’s Renaissance.” Or sometimes, said Johnson: “Richardson’s Renaissance” — because during Richardson’s presidency, enrollment doubled, the campus expanded with new buildings and new schools were added, including a school of architecture and a school of social work.

Richardson’s work put a spotlight, too, on the funding disparities faced by HBCUs across the country. They are more likely than other schools to rely upon federal, state and local funding — money that has faced budget cuts in recent years. Compared to other universities and colleges, HBCUs get a higher percentage of their revenue from tuition and less from private gifts and grants, according to one study.

In testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives in 2008, Richardson emphasized the mission of HBCUs when he told lawmakers that Black schools like his educated the most talented Black students but also sought to attract students who didn’t consider, or thought they couldn’t afford, to go to college. “We can make them the scientists and the engineers and the teachers and the professors — all of those things,” he said. But only if “we can have our institutions develop to a level of comparability and parity so that we are as competitive as other institutions.”

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms1 month ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers3 months ago

Jobs & Careers3 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Funding & Business3 months ago

Funding & Business3 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries