AI Insights

Tolstoy’s Complaint: Mission Command in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

What will become of battlefield command in the years ahead? This question is at the heart of the US Army’s once-in-a-generation reforms now underway. In search of answers, the Army looks to Ukraine. Events there suggest at least two truths. One is that decentralized command, which the US Army calls mission command and claims as its mode, will endure as a virtue. A second is that future commanders will use artificial intelligence to inform every decision—where to go, whom to kill, and whom to save. The recently announced Army Transformation Initiative indicates the Army intends to act on both.

But from these lessons there arises a different dilemma: How can an army at once preserve a culture of decentralized command and integrate artificial intelligence into its every task? Put another way, if at all echelons commanders rely on artificial intelligence to inform decisions, do they not risk just another form of centralization, not at the top, but within an imperfect model? To understand this dilemma and to eventually resolve it, the US Army would do well to look once again to the Ukrainian corner of the map, though this time as a glance backward two centuries, so that it might learn from a young redleg in Crimea named Leo Tolstoy.

What Tolstoy Saw

Before he became a literary titan, Leo Tolstoy was a twenty-something artillery officer. In 1854 he found himself in besieged port of Sevastopol, then under relentless French and British shelling, party to the climax of the Crimean War. When not tending to his battery on the city’s perilous Fourth Bastion, Tolstoy wrote dispatches about life under fire for his preferred journal in Saint Petersburg, The Contemporary. These dispatches, read across literate Russia for their candor and craft, made Tolstoy famous. They have since been compiled as The Sebastopol Sketches and are considered by many to be the first modern war reportage. Their success confirmed for Tolstoy that to write was his life’s calling, and when the Crimean War ended, he left military service so that he might do so full-time.

But once a civilian Tolstoy did not leave war behind, at least not as a subject matter. Until he died, he mined his time in uniform for the material of his fiction. In that fiction, most prominently the legendary accounts of the battles of Austerlitz and Borodino found in War and Peace, one can easily detect what he thought of command. Tolstoy’s contention is that the very idea of command itself is practically a fiction, so tenuous is the relationship between what commanders visualize, describe, and direct and what in fact happens on the battlefield. The worst officers in Tolstoy’s stories do great harm by vainly supposing they understand battles at hand when they in fact haven’t the faintest idea of what’s going on. The best officers are at peace with their inevitable ignorance and rather than fighting it, gamely project a calm that inspires their men. Either way, most officers wander the battlefield, blinded by gun smoke or folds in the earth, only later making up stories to explain what happened, stories others wrongly take as credible witness testimony.

Command or Hallucination?

Students of war may wonder whether Tolstoy was saying anything Carl von Clausewitz had not already said in On War, published in 1832. After all, there Clausewitz made famous allowances for the way the unexpected and the small both shape battlefield outcomes, describing their effects as “friction,” a term that still enjoys wide use in the US military today. But the friction metaphor itself already hints at one major difference between Clausewitz’s understanding of battle and Tolstoy’s. For Clausewitz all the things that go sideways in war amount to friction impeding the smooth operation of a machine at work on the battlefield, a machine begotten of an intelligent design and consisting of interlocking parts that fail by exception. As Tolstoy sees it, there is no such machine, except in the imagination of largely ineffectual senior leaders, who, try as they might, cannot realize their designs on the battlefield.

Tolstoy thus differed from Clausewitz by arguing that commanders not only fail to anticipate friction, but outright hallucinate. They see patterns on the battlefield where there are none and causes where there is only coincidence. In War and Peace, Pyotr Bagration seeks permission to start the battle at Austerlitz when it is already lost, Moscow burns in 1814 not because Kutuzov ordered it but because the firefighters fled the city, and Russians’ masterful knockout flank at Tarutino occurs not in accordance with a preconceived plan but by an accident of logistics. Yet historians and contemporaries alike credit Bagration and Kutuzov for the genius of these events—to say nothing of Napoleon, whom Tolstoy casts as a deluded egoist, “a child, who, holding a couple of strings inside a carriage, thinks he is driving it.”

Why then, per Tolstoy, do the commanders and historians credit such plans with unrelated effects? Tolstoy answers this in a typical philosophical passage of War and Peace: “The human mind cannot grasp the causes of events in their completeness,” but “the desire to find those causes is implanted in the human soul.” People, desirous of coherence but unable to espy the many small causes of events, instead see grand things and great men that are not there. Here Tolstoy makes a crucial point—it is not that there are no causes of events, just that the causes are too numerous and obscure for humans to know. These causes Tolstoy called “infinitesimals,” and to find them one must “leave aside kings, ministers, and generals” and instead study “the small elements by which the masses are moved.”

This is Tolstoy’s complaint. He lodged it against the great man theorists of history, then influential, who supposed great men propelled human events through genius and will. But it also can be read as a strong case for mission command, for Tolstoy’s account of war suggests that not only is a decentralized command the best sort of command—it is the only authentic command at all. Everything else is illusory. High-echelon commanders’ distance from the fight, from the level of the grunt or the kitchen attendant, allows their hallucinations to persist unspoiled by reality far longer than those below them in rank. The leader low to the ground is best positioned to integrate the infinitesimals into an understanding of the battlefield. That integration, as Isaiah Berlin writes in his great Tolstoy essay “The Hedgehog and Fox,” is more so “artistic-psychological” work than anything else. And what else are the “mutual trust” and “shared understanding,” which Army doctrine deems essential to mission command, but the products of an artful, psychological process?

From Great Man Theory to Great Model Theory

Perhaps no one needs Tolstoy to appreciate mission command. Today American observers see everywhere on the battlefields of Ukraine proof of its wisdom. They credit the Ukrainian armed forces with countering their Russian opponents’ numerical and material superiority by employing more dynamic, decentralized command and control, which they liken to the US Army’s own style. Others credit Ukrainians’ use of artificial intelligence for myriad battlefield functions, and here the Ukrainians are far ahead of the US Army. Calls abound to catch up by integrating artificial intelligence into data-centric command-and-control tools, staff work, and doctrine. The relationship between these two imperatives, to integrate artificial intelligence and preserve mission command, has received less attention.

At first blush, artificial intelligence seems a convincing answer to Tolstoy’s complaint. In “The Hedgehog and the Fox” Isaiah Berlin summarized that complaint this way:

Our ignorance is due not to some inherent inaccessibility of the first causes, only their multiplicity, the smallness of the ultimate units, and our own inability to see and hear and remember and record and co-ordinate enough of the available material. Omniscience is in principle possible even to empirical beings, but, of course, in practice unattainable.

Can one come up with a better pitch for artificial intelligence than that? Is not artificial intelligence’s alleged value proposition for the commander its ability to integrate all the Tolstoyan infinitesimals, those “ultimate units,” then project it, perhaps on a wearable device, for quick reference by the dynamic officer pressed for time by an advancing enemy? Put another way, can’t a great model deliver on the battlefield what a great man couldn’t?

The trouble is threefold. Whatever model or computer vision or multimodal system we call “artificial intelligence” and incorporate into a given layer of a command-and-control platform represents something like one mind, but not many minds, so each instance wherein a leader outsources analysis to that artificial intelligence is another instance of centralization. Second, the models we have are disposed to patterns and to hubris, so are more a replication than a departure from the hallucinating commanders Tolstoy so derided. Finally, leaders may reject the evidence of their eyes and ears in deference to artificial intelligence because it enjoys the credibility of dispassionate computation, thereby forgoing precisely the ground-level inputs that Tolstoy pointed out were most important for understanding battle.

Consider the centralization problem. Different models may be in development for different uses across the military, but the widespread fielding of any artificial intelligence–enabled command-and-control system risks proliferating the same model across the operational army. If the purpose of mission command were strictly to hasten battlefield decisions by replicating the mind of a higher command within junior leaders, then the threat of centralization would be irrelevant because artificial intelligence would render mission command obsolete. But Army Doctrinal Pamphlet 6-0 lists as mission command’s purpose also the levering of “subordinate ingenuity”—something that centralization denies. In aggregate one risks giving every user the exact same coach, if not the exact same commander, however brilliant that coach or commander might be.

Such a universal coach, like a universal compass or rifle, might not be so bad, were it not for the tendency of that universal coach to hallucinate. That large language models make things up and then confidently present them as truth is not news, but it is also not going away. Nor is those models’ basic function, which is to seek patterns and then extend them. Computer vision likewise produces false positives. This “illusion of thinking,” to paraphrase recent research, severely limits the capacity of artificial intelligence to tackle novel problems or process novel environments. Tolstoy observes that during the invasion of Russia “a war began which did not follow any previous traditions of war,” yet Napoleon “did not cease to complain . . . that the war was being carried on contrary to all the rules—as if there were any rules for killing people.” In this way Tolstoy ascribes Napoleon’s disastrous defeat at Borodino precisely to the sort of error artificial intelligence is prone to make—the faulty assumption that the rules that once applied extend forward mechanically. There is thus little difference between the sort of prediction for which models are trained and the picture of Napoleon in War and Peace on the eve of his arrival in Moscow. He imagined a victory that the data on which he had trained indicated he ought expect but that ultimately eludes him.

Such hallucinations are compounded by models’ systemic overconfidence. Research suggests that, like immature officers, models prefer to confidently proffer an answer than confess they just do not know. It is then not hard to imagine artificial intelligence processing incomplete reports of enemy behavior on the battlefield, deciding that the behavior conforms to a pattern, filling in gaps the observed data leaves, then confidently predicting an enemy course of action disproven by what a sergeant on the ground is seeing. It is similarly not hard to imagine a commander directing, at the suggestion of an artificial intelligence model, the creation of an engagement area anchored to hallucinated terrain or queued by a nonexistent enemy patrol. In the aggregate, artificial intelligence might effectively imagine entire scenarios like the ones on which it was trained playing out on a battlefield where it can detect little more than the distant, detonating pop of an explosive-laden drone.

To be fair, uniformed advocates of artificial intelligence have said explicitly that no one wants to replace human judgment. Often those advocates speak instead of artificial intelligence informing, enhancing, enabling, or otherwise making more efficient human commanders. Besides, any young soldier will point out that human commanders make all the same mistakes. Officers need no help from machines to spook at a nonexistent enemy or to design boneheaded engagement areas. So what’s the big deal with using artificial intelligence?

The issue is precisely that we regard artificial intelligence as more than human and so show it a deference researchers call “automation bias.” It’s all but laughable today to ascribe to any human the genius for seeing through war’s complexity that great man theorists once vested in Napoleon. But now many invest similar faith in the genius of artificial intelligence. Sam Altman of OpenAI refers to his project as the creation of “superintelligence.” How much daylight is there between the concept of superintelligence and the concept of the great man? We thus risk treating artificial intelligence as the Napoleon that Napoleon could not be, the genius integrator of infinitesimals, the protagonist of the histories that Tolstoy so effectively demolished in War and Peace. And if we regard artificial intelligence as the great man of the history, can we expect a young lieutenant to resist its recommendations?

What Is to Be Done?

Artificial intelligence, in its many forms, is here to stay. The Army cannot afford in this interwar moment a Luddite reflex. It must integrate artificial intelligence into its operations. Anybody who has attempted to forecast when a brigade will be ready for war or when a battalion will need fuel resupply or when a soldier will need a dental checkup knows how much there is to be gained from narrow artificial intelligence, which promises to gain immense efficiencies in high-iteration, structured, context-independent tasks. Initiatives like Next Generation Command and Control promise as much. But the risks to mission command posed by artificial intelligence are sizable. Tolstoy’s complaint is of great use to the Army as it seeks to understand and mitigate those risks.

The first way to mitigate the risk artificial intelligence poses to mission command is to limit the use of it those high-volume, simple tasks. Artificial intelligence is ill-suited for low-volume, highly complex, context-dependent, deeply human endeavors—a good description of warfare—and so its role in campaign design, tactical planning, the analysis of the enemy, and the leadership of soldiers should be small. Its use in such endeavors is limited to expediting calculations of the small inputs human judgment requires. This notion of human-machine teaming in war is not new (it has been explored well by others, including Major Amanda Collazzo via the Modern War Institute). But amid excitement for it, the Army risks forgetting that it must carefully draw and jealously guard the boundary between human and machine. It must do so not only for ethical reasons, but because, as Tolstoy showed to such effect, command in battle humbles the algorithmic mind—of man or machine. Put in Berlin’s terms, command remains “artistic-psychological” work, and that work, even now, remains human work. Such caution does not require a ban on machine learning and artificial intelligence in simulations or wargames, which would be self-sabotage, but it does require that officers check any temptation to outsource the authorship of campaigns or orders to a model—something which sounds obvious now, but soon may not.

The second way is to program into the instruction of Army leaders a healthy skepticism of artificial intelligence. This might be done first by splitting the instruction of students into analog and artificial intelligence–enabled segments, not unlike training mortarmen to plan fire missions with a plotting board as well as a ballistic computer. Officers must first learn to write plans and direct their execution without aid before incorporating artificial intelligence into the process. Their ability to do so must be regularly recertified throughout their careers. Classes on machine learning that highlight the dependency of models on data quality must complement classes on intelligence preparation of the battlefield. Curriculum designers will rightly point out that curricula are already overstuffed, but if artificial intelligence–enabled command and control is as revolutionary as its proponents suggest, it demands a commensurate change in the way we instruct our commanders.

The third way to mitigate the risks posed is to program the same skepticism of artificial intelligence into training. When George Marshall led the Infantry School during the interwar years, he and fellow instructor Joseph Stilwell forced students out of the classroom and into the field for unscripted exercises, providing them bad maps so as to simulate the unpredictability of combat. Following their example, the Army should deliberately equip leaders during field exercises and wargames with hallucinatory models. Those leaders should be evaluated on their ability to recognize when the battlefield imagined by their artificial intelligence–enabled command-and-control platforms and the battlefield they see before them differ. And when training checklists require that for a unit to be fully certified in a task it must perform that task under dynamic, degraded conditions, “degraded” must come to include hallucinatory or inoperable artificial intelligence.

Even then, Army leaders must never forget what Tolstoy teaches us: that command is a contingent, human endeavor. Often battles represent idiosyncratic problems of their own, liable to defy patterns. Well-trained young leaders’ proximity to those problems is an asset rather than a liability. For that proximity they can spot on the battlefield infinitesimally small things that great data ingests cannot capture. A philosophy of mission command, however fickle and at times frustrating, best accommodates the insights that arise from that proximity. Only then can the Army see war’s Tolstoyan infinitesimals through the gun smoke and have any hope of integrating them.

Theo Lipsky is an active duty US Army captain. He is currently assigned as an instructor to the Department of Social Sciences at the US Military Academy at West Point. He holds a master of public administration from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and a bachelor of science from the US Military Academy. His writing can be found at theolipsky.substack.com.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Zoe Morris, US Army

AI Insights

How AI is eroding human memory and critical thinking

AI Insights

The human thinking behind artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence is built on the thinking of intelligent humans, including data labellers who are paid as little as US$1.32 per hour. Zena Assaad, an expert in human-machine relationships, examines the price we’re willing to pay for this technology. This article was originally published in the Cosmos Print Magazine in December 2024.

From Blade Runner to The Matrix, science fiction depicts artificial intelligence as a mirror of human intelligence. It’s portrayed as holding a capacity to evolve and advance with a mind of its own. The reality is very different.

The original conceptions of AI, which hailed from the earliest days of computer science, defined it as the replication of human intelligence in machines. This definition invites debate on the semantics of the notion of intelligence.

Can human intelligence be replicated?

The idea of intelligence is not contained within one neat definition. Some view intelligence as an ability to remember information, others see it as good decision making, and some see it in the nuances of emotions and our treatment of others.

As such, human intelligence is an open and subjective concept. Replicating this amorphous notion in a machine is very difficult.

Software is the foundation of AI, and software is binary in its construct; something made of two things or parts. In software, numbers and values are expressed as 1 or 0, true or false. This dichotomous design does not reflect the many shades of grey of human thinking and decision making.

Not everything is simply yes or no. Part of that nuance comes from intent and reasoning, which are distinctly human qualities.

To have intent is to pursue something with an end or purpose in mind. AI systems can be thought to have goals, in the form of functions within the software, but this is not the same as intent.

The main difference is goals are specific and measurable objectives whereas intentions are the underlying purpose and motivation behind those actions.

You might define the goals as ‘what’, and intent as ‘why’.

To have reasoning is to consider something with logic and sensibility, drawing conclusions from old and new information and experiences. It is based on understanding rather than pattern recognition. AI does not have the capacity for intent and reasoning and this challenges the feasibility of replicating human intelligence in a machine.

There is a cornucopia of principles and frameworks that attempts to address how we design and develop ethical machines. But if AI is not truly a replication of human intelligence, how can we hold these machines to human ethical standards?

Can machines be ethical?

Ethics is a study of morality: right and wrong, good and bad. Imparting ethics on a machine, which is distinctly not human, seems redundant. How can we expect a binary construct, which cannot reason, to behave ethically?

Similar to the semantic debate around intelligence, defining ethics is its own Pandora’s box. Ethics is amorphous, changing across time and place. What is ethical to one person may not be to another. What was ethical 5 years ago may not be considered appropriate today.

These changes are based on many things; culture, religion, economic climates, social demographics, and more. The idea of machines embodying these very human notions is improbable, and so it follows that machines cannot be held to ethical standards. However, what can and should be held to ethical standards are the people who make decisions for AI.

Contrary to popular belief, technology of any form does not develop of its own accord. The reality is their evolution has been puppeteered by humans. Human beings are the ones designing, developing, manufacturing, deploying and using these systems.

If an AI system produces an incorrect or inappropriate output, it is because of a flaw in the design, not because the machine is unethical.

The concept of ethics is fundamentally human. To apply this term to AI, or any other form of technology, anthropomorphises these systems. Attributing human characteristics and behaviours to a piece of technology creates misleading interpretations of what that technology is and is not capable of.

Decades long messaging about synthetic humans and killer robots have shaped how we conceptualise the advancement of technology, in particular, technology which claims to replicate human intelligence.

AI applications have scaled exponentially in recent years, with many AI tools being made freely available to the general public. But freely accessible AI tools come at a cost. In this case, the cost is ironically in the value of human intelligence.

The hidden labour behind AI

At a basic level, artificial intelligence works by finding patterns in data, which involves more human labour than you might think.

ChatGPT is one example of AI, referred to as a large language model (LLM). ChatGPT is trained on carefully labelled data which adds context, in the form of annotations and categories, to what is otherwise a lot of noise.

Using labelled data to train an AI model is referred to as supervised learning. Labelling an apple as “apple”, a spoon as “spoon”, a dog as “dog”, helps to contextualise these pieces of data into useful information.

When you enter a prompt into ChatGPT, it scours the data it has been trained on to find patterns matching those within your prompt. The more detailed the data labels, the more accurate the matches. Labels such as “pet” and “animal” alongside the label “dog” provide more detail, creating more opportunities for patterns to be exposed.

Data is made up of an amalgam of content (images, words, numbers, etc.) and it requires this context to become useful information that can be interpreted and used.

As the AI industry continues to grow, there is a greater demand for developing more accurate products. One of the main ways for achieving this is through more detailed and granular labels on training data.

Data labelling is a time consuming and labour intensive process. In absence of this work, data is not usable or understandable by an AI model that operates through supervised learning.

Despite the task being essential to the development of AI models and tools, the work of data labellers often goes entirely unnoticed and unrecognised.

Data labelling is done by human experts and these people are most commonly from the Global South – Kenya, India and the Philippines. This is because data labelling is labour intensive work and labour is cheaper in the Global South.

Data labellers are forced to work under stressful conditions, reviewing content depicting violence, self-harm, murder, rape, necrophilia, child abuse, bestiality and incest.

Data labellers are pressured to meet high demands within short timeframes. For this, they earn as little as US$1.32 per hour, according to TIME magazine’s 2023 reporting, based on an OpenAI contract with data labelling company Sama.

Countries such as Kenya, India and the Philippines incur less legal and regulatory oversight of worker rights and working conditions.

Similar to the fast fashion industry, cheap labour enables cheaply accessible products, or in the case of AI, it’s often a free product.

AI tools are commonly free or cheap to access and use because costs are being cut around the hidden labour that most people are unaware of.

When thinking about the ethics of AI, cracks in the supply chain of development rarely come to the surface of these discussions. People are more focused on the machine itself, rather than how it was created. How a product is developed, be it an item of clothing, a TV, furniture or an AI-enabled capability, has societal and ethical impacts that are far reaching.

A numbers game

In today’s digital world, organisational incentives have shifted beyond revenue and now include metrics around the number of users.

Releasing free tools for the public to use exponentially scales the number of users and opens pathways for alternate revenue streams.

That means we now have a greater level of access to technology tools at a fraction of the cost, or even at no monetary cost at all. This is a recent and rapid change in the way technology reaches consumers.

In 2011, 35% of Americans owned a mobile phone. By 2024 this statistic increased to a whopping 97%. In 1973, a new TV retailed for $379.95 USD, equivalent to $2,694.32 USD today. Today, a new TV can be purchased for much less than that.

Increased manufacturing has historically been accompanied by cost cutting in both labour and quality. We accept poorer quality products because our expectations around consumption have changed. Instead of buying things to last, we now buy things with the expectation of replacing them.

The fast fashion industry is an example of hidden labour and its ease of acceptance in consumers. Between 1970 and 2020, the average British household decreased their annual spending on clothing despite the average consumer buying 60% more pieces of clothing.

The allure of cheap or free products seems to dispel ethical concerns around labour conditions. Similarly, the allure of intelligent machines has created a facade around how these tools are actually developed.

Achieving ethical AI

Artificial intelligence technology cannot embody ethics; however, the manner in which AI is designed, developed and deployed can.

In 2021, UNESCO released a set of recommendations on the ethics of AI, which focus on the impacts of the implementation and use of AI. The recommendations do not address the hidden labour behind the development of AI.

Misinterpretations of AI, particularly those which encourage the idea of AI developing with a mind of its own, isolate the technology from the people designing, building and deploying that technology. These are the people making decisions around what labour conditions are and are not acceptable within their supply chain, what remuneration is and isn’t appropriate for the skills and expertise required for data labelling.

If we want to achieve ethical AI, we need to embed ethical decision making across the AI supply chain; from the data labellers who carefully and laboriously annotate and categorise an abundance of data through to the consumers who don’t want to pay for a service they have been accustomed to thinking should be free.

Everything comes at a cost, and ethics is about what costs we are and are not willing to pay.

AI Insights

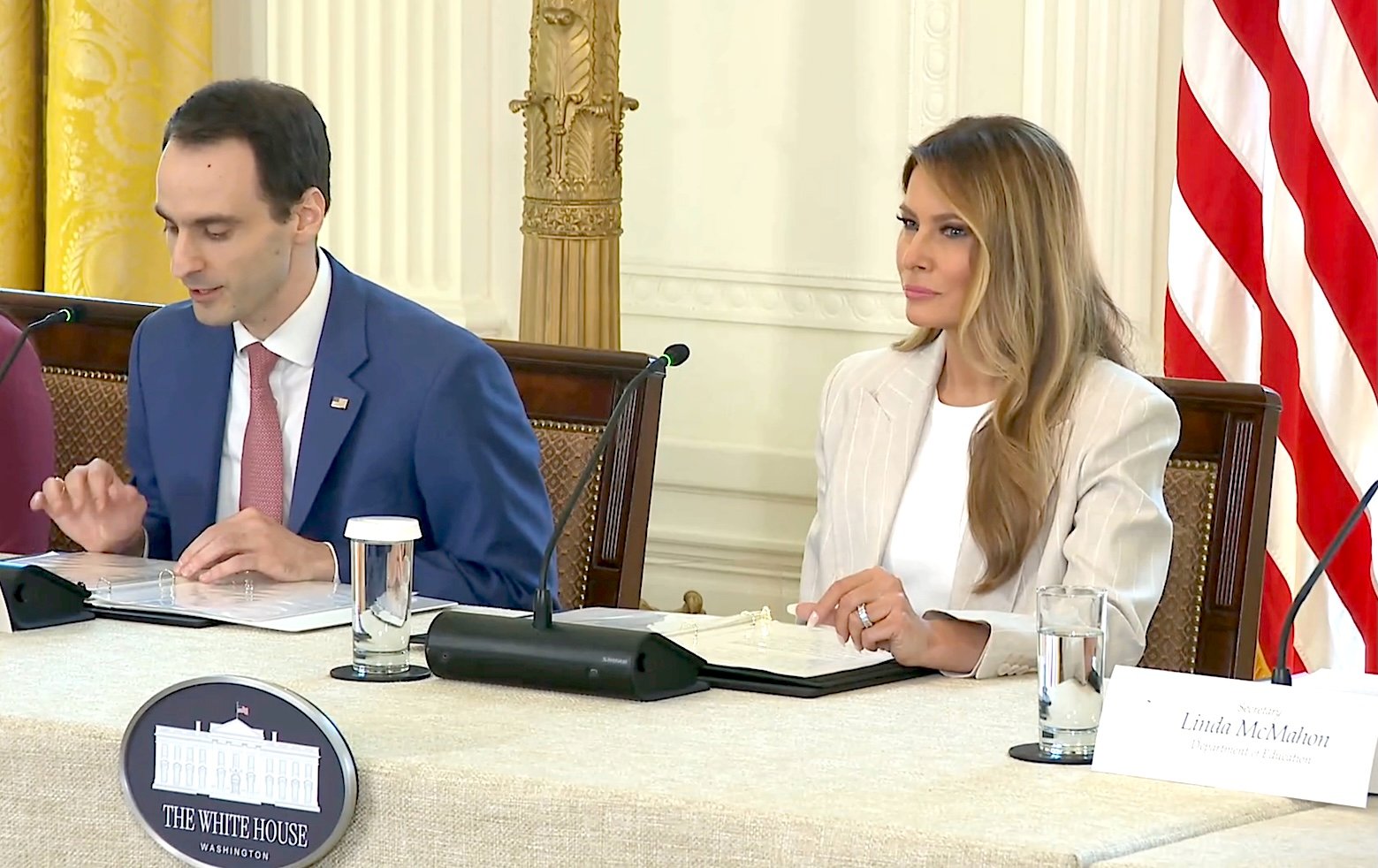

‘The robots are here’: Melania Trump encourages America to lead world in artificial intelligence at White House event

A “moment of wonder” is how First Lady Melania Trump described the era of artificial intelligence during rare public remarks Thursday at a White House event on AI education.

“It is our responsibility to prepare children in America,” Trump said as she hosted the White House Task Force on Artificial Intelligence Education in Washington, D.C. Citing self-driving cars, robots in the operating room, and drones redefining war, Trump said “every one of these advancements is powered by AI.”

The meeting, attended by The Lion and other reporters, also included remarks from task force members, including Cabinet Secretaries Christopher Wright (Energy), Linda McMahon (Education), Brooke Rollins (Agriculture), and Lori Chavez-DeRemer (Labor), as well as technology leaders in the private sector.

“The robots are here. Our future is no longer science fiction,” Trump added, noting that AI innovation is spurring economic growth and will “serve as the underpinning of every business sector in our nation,” including science, finance, education, and design.

Trump predicted AI will unfold as the “single largest growth category in our nation” during President Donald Trump’s administration, and she would not be surprised if AI “becomes known as the greatest engine of progress” in America’s history.

“But as leaders and parents, we must manage AI’s growth responsibly,” she warned. “During this primitive stage, it is our duty to treat AI as we would our own children – empowering, but with watchful guidance.”

Thursday’s event marked the AI task force’s second meeting since President Trump signed an executive order in April to advance AI education among American youth and students. The executive order set out a policy to “promote AI literacy and proficiency among Americans” by integrating it into education, providing training for teachers, and developing an “AI-ready workforce.”

The first lady sparked headlines for her embrace of AI after using it to narrate her audiobook, Melania. She also launched a national Presidential AI Challenge in August, encouraging students and teachers to “unleash their imagination and showcase the spirit of American innovation.” The challenge urges students to submit projects that involve the study or use of AI to address community challenges and encourages teachers to use “creative approaches” for using AI in K-12 education.

At the task force meeting, Trump called for Americans to “lead in shaping a new magnificent world” in the AI era, and said the Presidential AI Challenge is the “first major step to galvanize America’s parents, educators and students with this mission.”

During the event, McMahon quipped that Barron Trump, the Trumps’ college-aged son, was “helping you with a little bit of this as well,” receiving laughs from the audience. The education secretary also said her department is working to embrace AI through its grants, future investments and even its own workforce.

“In supporting our current grantees, we’ve issued a Dear Colleague letter telling anyone who has received an ED grant that AI tools and technologies are allowable use of federal education funds,” she said. “Our goal is to empower states and schools to begin exploring AI integration in a way that works best for their communities.”

Rollins spoke next, noting that rural Americans are too often “left behind” without the same technological innovations that are available in urban areas. “We cannot let that happen with AI,” the agriculture secretary said.

“I want to say that President Trump has been very clear, the United States will lead the world in artificial intelligence, period, full stop. Not China, not of our other foreign adversaries, but America,” Rollins said. “And with the First Lady’s leadership and the presidential AI challenge. We are making sure that our young people are ready to win that race.”

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms4 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi