Education

US visa applicants required to interview in home country

Effective as of September 6, all nonimmigrant US visa applicants including international students must schedule interviews at their local US embassy or consulate, or face an increased risk of rejection, the State Department has announced.

“Applicants who scheduled nonimmigrant interviews at a US embassy or consulate outside of their country of nationality or residence might find that it will be more difficult to qualify for the visa,” the department warned.

Fees paid for such applications will not be refunded and cannot be transferred, said the department, adding that applicants would have to demonstrate residence in the country where they are applying.

The directive puts an end to a pandemic-era practice of students bypassing long wait times at home by scheduling visa appointments from a third country.

Stakeholders have raised concerns that the new rule could exacerbate wait times and disadvantage students whose local embassies are plagued by delays.

According to State Department data updated last month, individuals applying for student and exchange visitor visas at the US embassy in Abuja, Nigeria, currently must wait 14-months before obtaining an interview.

Meanwhile, the next available F, M, and J visa appointments at consulates in Accra, Ghana and Karachi, Pakistan, are not for another 11 and 10.5 months respectively.

Applicants who scheduled nonimmigrant interviews at a US embassy or consulate outside of their country of nationality or residence might find that it will be more difficult to qualify for the visa

US State Department

The new rule comes after a near month-long pause on new student visa interviews this summer saw major delays and cancelled appointments at embassies across the globe, preventing some international students from enrolling at US colleges this semester.

Enhanced social media vetting for all student visa applications is also believed to be contributing to the delays.

Existing nonimmigrant visa appointments “will generally not be cancelled,” said the department, adding that: “Rare exceptions may also be made for humanitarian or medical emergencies or foreign policy reasons.”

Nationals of countries where the US is not conducting routine visa operations have been instructed to apply at the following designated alternatives:

| National of: | Designated location (s): |

| Afghanistan | Islamabad |

| Belarus | Vilnius, Warsaw |

| Chad | Yaoundé |

| Cuba | Georgetown |

| Haiti | Nassau |

| Iran | Dubai |

| Libya | Tunis |

| Niger | Ouagadougou |

| Russia | Astana, Warsaw |

| Somalia | Nairobi |

| South Sudan | Nairobi |

| Sudan | Cairo |

| Syria | Amman |

| Ukraine | Krakow, Warsaw |

| Venezuela | Bogota |

| Yemen | Riyadh |

| Zimbabwe | Johannesburg |

The State Department did not immediately respond to The PIE’s request for comment.

Education

Empowering Educators: Unveiling AI's Role in Modern Classrooms – Devdiscourse

Education

Students, schools race to save clean energy projects in face of Trump deadline

Tanish Doshi was in high school when he pushed the Tucson Unified School District to take on an ambitious plan to reduce its climate footprint. In Oct. 2024, the availability of federal tax credits encouraged the district to adopt the $900 million plan, which involves goals of achieving net-zero emissions and zero waste by 2040, along with adding a climate curriculum to schools.

Now, access to those funds is disappearing, leaving Tucson and other school systems across the country scrambling to find ways to cover the costs of clean energy projects.

The Arizona school district, which did not want to impose an economic burden on its low-income population by increasing bonds or taxes, had expected to rely in part on federal dollars provided by the Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act, Doshi said.

But under HR1, or the “one big, beautiful bill,” passed on July 4, Tucson schools will not be able to receive all of the expected federal funding in time for their upcoming clean energy projects. The law discontinues many clean energy tax credits, including those used by schools for solar power and electric vehicles, created under the IRA. When schools and other tax-exempt organizations receive these credits, they come in the form of a direct cash reimbursement.

At the same time, Tucson and thousands of districts across the country that were planning to develop solar and wind power projects are now forced to decide between accelerating them to try to meet HR1’s fast-approaching “commence construction” deadline of June 2026, finding other sources of funding or hitting pause on their plans. Tina Cook, energy project manager for Tucson schools, said the district might have to scale back some of its projects unless it could find local sources of funding.

“Phasing out the tax credits for wind and solar energy is going to make a huge, huge difference,” said Doshi, 18, now a first-year college student. “It ends a lot of investments in poor and minority communities. You really get rid of any notion of environmental justice that the IRA had advanced.”

The tax credits in the IRA, the largest legislative investment in climate projects in U.S. history, had marked a major opportunity for schools and colleges to reduce their impact on the environment. Educational institutions are significant contributors to climate change: K-12 school infrastructure, for example, releases at least 41 million metric tons of emissions per year, according to a paper from the Annenberg Institute at Brown University. The K-12 school system’s buses — some 480,000 — and meals also produce significant emissions and waste. Clean energy projects supported by the IRA were helping schools not only to limit their climate toll but also to save money on energy costs over the long term and improve student health, advocates said.

As a result, many students, consultants and sustainability leaders said, they have no plans to abandon clean energy projects. They said they want to keep working to cut emissions, even though that may be more difficult now.

Related: Become a lifelong learner. Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter featuring the most important stories in education.

Sara Ross, cofounder of UndauntedK12, which helps school districts green their operations, divided HR1’s fallout on schools into three categories: the good, the bad and the ugly.

On the bright side, she said, schools can still get up to 50 percent off for installing ground source heat pumps — those credits will continue — to more efficiently heat schools. The network of pipes in a ground source pump cycles heat from the shallow earth into buildings.

In the “bad” category, any electric vehicle acquired after Sept. 30 of this year will not be eligible for tax credits — drastically accelerating the IRA’s phase-out timeline by seven years. That applies to electric school buses as well as electric vehicle charging stations at schools. EPA’s Clean School Bus Program still exists for two more years and covers two-thirds of the funding for all electric school buses districts acquire in that time. The remaining one-third, however, was to be covered by federal and state tax credits.

The expiration of the federal tax credits could cost a district up to $40,000 more per vehicle, estimated Sue Gander, director of the Electric School Bus Initiative run by the nonprofit World Resources Institute.

Related: So much for saving the planet. Climate jobs, and many others, evaporate for 2025 grads

Solar projects will see the most “ugly” effects of HR1, Ross said.

Los Angeles Unified School District is planning to build 21 solar projects on roofs, carports and other structures, plus 13 electric vehicle charging sites, as part of an effort to reduce energy costs and achieve 100 percent renewable energy by 2040. The district anticipated receiving around $25 million in federal tax credits to help pay for the $90 million contract, said Christos Chrysiliou, chief eco-sustainability officer for the district. With the tight deadlines imposed by HR1, the district can no longer count on receiving that money.

“It’s disappointing,” Chrysiliou said. “It’s nice to be able to have that funding in place to meet the goals and objectives that we have.”

LAUSD is looking at a small portion of a $9 billion bond measure passed last year, as well as utility rebates, third-party financing and grants from the California Energy Commission, to help make up for some of the gaps in funding.

Many California State University campuses are in a similar position as they work to install solar to meet the system’s goal of carbon neutrality by 2045, said Lindsey Rowell, CSU’s chief energy, sustainability and transportation officer.

Tariffs on solar panel materials from overseas and the early sunsetting of tax credits mean that “the cost of these projects are becoming prohibitive for campuses,” Rowell said.

Sweeps of undocumented immigrants in California may also lead to labor shortages that could slow the pace of construction, Rowell added. “Limiting the labor force in any way is only going to result in an increased cost, so those changes are frightening as well,” she said.

New Treasury Department guidance, issued Aug. 15, made it much harder for projects to meet the threshold needed to qualify for the tax credits. Renewable energy projects previously qualified for credits once a developer spent 5 percent of a project’s cost. But the guidelines have been tightened — now, larger projects must pass a “physical work test,” meaning “significant physical labor has begun on a site,” before they can qualify for credits. With the construction commencement deadline looming next June, these will likely leave many projects ineligible for credits.

“The rules are new, complex [and] not widely understood,” Ross said. “We’re really concerned about schools’ ability to continue to do solar projects and be able to effectively navigate these new rules.”

Schools without “fancy legal teams” may struggle to understand how the new tax credit changes in HR1 will affect their finances and future projects, she added.

Some universities were just starting to understand how the IRA tax credits could help them fund projects. Lily Strehlow, campus sustainability coordinator at the University of Wisconsin, Eau-Claire, said the planning cycle for clean energy projects at the school can take ten years. The university is in the process of adding solar to the roof of a large science building, and depending on the date of completion, the project “might or might not” qualify for the credits, she said.

“At this point, everybody’s holding their breath,” said Rick Brown, founder of California-based TerraVerde Energy, a clean energy consultant to schools and agencies.

Brown said that none of his company’s projects are in a position where they’re not going to get done, but the company may end up seeing fewer new projects due to a higher cost of equipment.

Tim Carter, president of Second Nature, which supports climate work in education, added that colleges and universities are in a broader period of uncertainty, due to larger attacks from the Trump administration, and are not likely to make additional investments at this time: “We’re definitely in a wait and see.”

Related: A government website teachers rely on is in peril

For youth activists, the fallout from HR1 is “disheartening,” Doshi said.

Emma and Molly Weber, climate activists since eighth grade, said they are frustrated. The Colorado-based twins, who will start college this fall, helped secure the first “Green New Deal for Schools” resolution in the nation in the Boulder Valley School District. Its goals include working toward a goal of Zero Net Energy by 2050, making school buildings greener, creating pathways to green jobs and expanding climate change education.

“It feels very demoralizing to see something you’ve been working so hard at get slashed back, especially since I’ve spoken to so many students from all over the country about these clean energy tax credits, being like, ‘These are the things that are available to you, and this is how you can help convince your school board to work on this,’” Emma Weber said.

The Webers started thinking about other creative ways to pay for the clean energy transition and have settled on advocating for state-level legislation in the form of a climate superfund, where major polluters in a community would be responsible for contributing dollars to sustainability initiatives.

Consultants and sustainability coordinators said that they don’t see the demand for renewable energy going away. “Solar is the cheapest form of energy. It makes sense to put it on every rooftop that we can. And that’s true with or without tax credits,” Strehlow said.

Contact editor Caroline Preston at 212-870-8965, via Signal at CarolineP.83 or on email at preston@hechingerreport.org.

This story about tax credits was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

Education

Maine Monitor: ‘Building the plane as we’re flying it’: How Maine schools are using generative AI in the classroom

By Kristian Moravec of the Maine Monitor

One platform, MagicSchool, has more than 8,500 educator accounts in Maine. As teachers and students increasingly turn to these tools, some school districts are working to codify guidelines for ethical use.

In Technology Director Mike Arsenault’s office at the Yarmouth School Department, papers and boxes sat on his desk — some of it swag from the tech company MagicSchool, one of several artificial intelligence programs the district is now using.

The AI platform, which was designed for educators, offers tools like a lesson planner, letter of recommendation producer, Individualized Education Plan drafter and even a classroom joke writer. The district pays about $10,000 a year for a MagicSchool enterprise package, and Arsenault said that his favorite element is the “Make it Relevant” tool, which prompts teachers to describe their class and what they’re studying and then generates activities that tie student interests to the subject.

“Because the question that students have asked forever is ‘why are we learning this,” Arsenault said, explaining that students should have clear examples of how lessons are useful outside of the classroom. “That’s something that AI is really good at.”

The district is one of many across Maine that is increasingly using AI in its classrooms. Some, like Yarmouth, have established formal AI guidelines. Others have not. MagicSchool told The Monitor that it has around 8,500 educator accounts active in Maine. This would equate to more than half of the state’s public school teachers, though anyone can sign up for a free educator account.

The state Department of Education does not yet have data on how many teachers or school districts are using AI, but said that based on the level of interest schools have for AI professional development, its use is widespread. The department is conducting a study to better understand how schools are integrating the new technology and hopes to release data next spring, according to a spokesperson.

The use of generative AI — a type of artificial intelligence that generates new text, images or other content, such as the technology used in ChatGPT — is prompting a growing debate in education. Critics see it as a tool that decreases critical thinking and helps students cheat, while advocates see it as a fixture that students must learn how to use ethically.

A majority of teachers across the country are growing familiar with AI for either personal or school use, and suspect that their students are using it widely as well, according to a 2024 study by the Center for Democracy and Technology.

As AI changes come at breakneck speed, leaders are pushing for its controlled use in schools. Roughly half of states have some form of AI guidance in place, according to the Sutherland Institute.

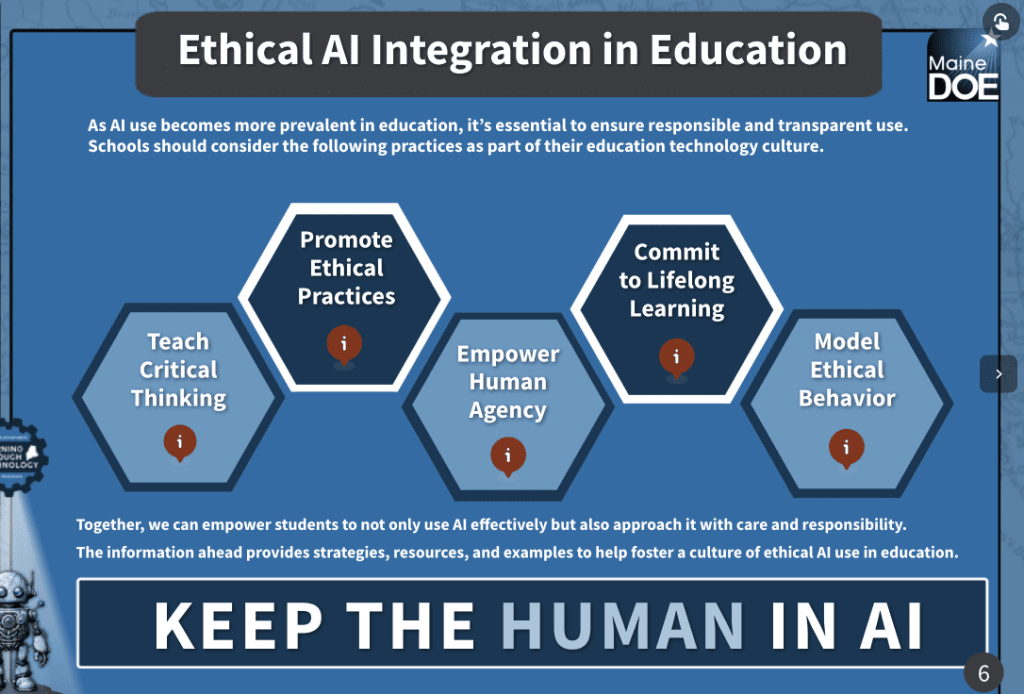

Maine introduced an interactive AI guidance toolkit earlier this year, which walks educators through ways they can integrate AI in the classroom from pre-Kindergarten to 12th grade and the questions to consider when doing so. Students in pre-Kindergarten through second grade could “use AI to generate art and have students collboarate [sic] to create a shared image,” according to the guidance, or high school students could “explore cybersecurity principles through ethical hacking simulations.”

The guidance encourages teachers to “keep the human in AI” by stopping to ask if its use is appropriate for the task, monitoring for accuracy and noting how AI was used.

The governor’s office launched a state AI Task Force last year to prepare Maine for the “opportunities and risks likely to result from advances in AI” in private industries, education and government. The task force’s education subgroup has met three times this year, and plans to release a report on AI use in Maine this fall.

For Yarmouth Superintendent Andrew Dolloff, it is important to help students tackle the increasingly popular technology in a safe environment. The district adopted its first set of AI guidelines last year, which emphasize that staff should be transparent and cite any use of generative AI, ensure student data privacy is protected, be cautious of bias and misinformation and understand the technology “as an evolving tool, not an infallible source.”

“AI is here to stay. It’s part of our lives. We’re all using it as adults on a daily basis. Sometimes without even knowing it or realizing that it’s AI,” Dolloff said. “So we changed our stance pretty quickly to understand that rather than trying to ban AI, we needed to find ways to effectively use it, and allow students to use it appropriately to expand their learning.”

Maine School Administrative District 75 — which serves Harpswell, Topsham, Bowdoin and Bowdoinham — adopted an AI policy earlier this year, though some school board members were hesitant to approve the policy over concerns that generative AI can help students cheat and produce misinformation, The Harpswell Anchor reported.

Some school districts, such as Regional School Unit 22, which serves Hampden, Newburgh, Winterport and Frankfort, have launched internal committees to guide AI use, while others, such as MSAD 15 in Gray and New Gloucester, are pursuing policies in the wake of controversy.

Earlier this year, a student at MSAD 15 alleged that a teacher graded a paper using AI, WGME reported. Superintendent Chanda Turner told The Maine Monitor that teachers are piloting programs that use AI to give feedback on papers, but are not using it to issue grades. The school board will be working on an AI policy for the district this school year, she said.

Nicole Davis, an AI and emerging technology specialist with the DOE who helped write the state guidelines, estimates that over 40 school districts in Maine have requested professional development for AI, and expects that interest will grow. She noted that guiding AI use can be a challenge, as the technology changes so quickly.

“We’re building the plane as we’re flying it,” Davis said.

‘I was stunned’

Julie York, a computer science teacher at South Portland High School, has long incorporated new technology into her teaching, and has found generative AI tools like ChatGPT and Google Gemini to be “incredibly useful.” She has used it to create voiceovers for presentations when she was tired, to help make rubrics and lesson plans and to build a chatbot that can answer questions during class, which she says helps her balance the amount of time she spends with each student.

“I don’t think there’s any educator who wakes up in the morning, and is like, ‘oh my god, I hope I can make a rubric today.’ I just don’t think you’re going to find any,” she said. “And there’s no teacher who isn’t tired.”

She vets all the AI resources she uses before integrating them into her work, and has discussions with her students about when using AI is appropriate. Student use is guided by the traffic light model: if an assignment is green, students can use AI under the guidance of a teacher, if it’s yellow that means limited use with teacher permission, and red means no AI. She makes these determinations depending on the type of assessment. If she wants them to be able to read code and understand what it does, for instance, then AI cannot be used. But if a student is coding a computer program, she said, then AI can be a useful tool.

AI can also help teachers accommodate diverse needs, York said, explaining that students who have trouble speaking in front of a class could use text-to-voice software to produce voiced-over videos. The district’s students speak several different languages, and she used AI to help her create an app that translates her speech into multiple languages while she’s teaching. It took her about an hour to make.

“I just sat there stunned at my computer. Just stunned,” York recalled.

Maine Education Association President Jesse Hargrove said that teachers are exploring the evolving AI landscape alongside their students, noting that AI can help create steps for science projects, or detect whether students cheated.

“I think it’s being used as a partner in the learning, but not a replacement for the thinking,” he said.

MEA’s approach to AI is guided by the National Education Association’s policy, which emphasizes putting educators at the center of education. However, Hargrove said that MEA does not have a stance on whether or not districts should adopt AI.

“We believe that AI should be enhancing the educational experience rather than replacing educators,” he said.

‘Click. Boom. Done.’

Maine’s AI guidance emphasizes that teachers should have clear expectations for AI use in the classroom. It recommends being specific about grade levels, lesson times, content and general student needs when prompting services like ChatGPT to generate lesson plans.

The state told The Monitor it does not recommend any AI tools in particular. Instead, the DOE said it encourages schools to research tools and consider data security, privacy and use.

But its guidance toolkit references a handful of specific programs. MagicSchool and Diffit are listed as tools that can help with accessibility in the classroom. Almanack, MagicSchool and Canva are noted as tools that can help boost student engagement.

The types of AI tools that educators use vary depending on their needs, Davis said, but there seem to be five tools that can assess papers, create study materials and help build curriculums that schools are turning to the most: Diffit, Brisk, Canva, MagicSchool and School AI.

“That batch of essays that’s looming? Brisk will help you grade them before the bell rings,” Brisk’s website reads. “Need a lesson plan for tomorrow? Click. Boom. Done.”

Use of these platforms is regulated by legal parameters for student data safety, such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and Maine’s Student Information Privacy Act. Technology companies must sign a data privacy agreement for the states in which they plan to operate. Maine’s data privacy agreement with MagicSchool, for instance, covers nine other states and sets guardrails for student data collection such as leaving ownership and control of data to “local education agencies.”

Some education-based AI companies also have their own parameters in place. MagicSchool, which was founded by former educator Adeel Khan, requires teachers to sign a best practices agreement, reminds them not to enter personal student information into AI prompts like an Individual Education Plan generator, and claims it erases any student information that gets entered into its system.

“We’re always iterating and trying to make things safer as we go,” Khan said, citing MagicSchool’s favorable rating for privacy on Common Sense Media, an organization that rates technology and digital media for children.

The federal government has also pushed for the use of AI in schools. In the spring, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to promote AI in education, and the federal Department of Education has since published a letter encouraging the use of grant funding to “support improved outcomes for learners through responsible integration of artificial intelligence.”

In late August, First Lady Melania Trump launched the Presidential AI Challenge: asking students to “create AI-based innovative solutions to community challenges.”

The White House is also running a pledge campaign, “Investing in AI Education,” asking technology companies to commit resources like funding, education materials, technology, professional development programs and access to technical expertise to K-12 students, teachers and families for the next four years. More than 100 entities have signed on, including MagicSchool.

In Maine, the DOE is working on broader AI professional development for teachers, with plans to launch a pilot course based on the state’s AI guidance toolkit, potentially as soon as this fall.

As Yarmouth starts the new school year, Arsenault said that AI should be integrated with the goal of preparing students for a future that will be filled with AI.

“We can do what many schools do and ignore it, or we can address it,” Arsenault said. “And if we address it with our students, we have the ability to frame the discussion on how it’s used, and have discussions with our students about how we want to see it used in our classrooms.”

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms4 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi