Education

How Maine schools are using generative AI in the classroom

In Technology Director Mike Arsenault’s office at the Yarmouth School Department, papers and boxes sat on his desk — some of it swag from the tech company MagicSchool, one of several artificial intelligence programs the district is now using.

The AI platform, which was designed for educators, offers tools like a lesson planner, letter of recommendation producer, Individualized Education Plan drafter and even a classroom joke writer. The district pays about $10,000 a year for a MagicSchool enterprise package, and Arsenault said that his favorite element is the “Make it Relevant” tool, which prompts teachers to describe their class and what they’re studying and then generates activities that tie student interests to the subject.

“Because the question that students have asked forever is ‘why are we learning this,” Arsenault said, explaining that students should have clear examples of how lessons are useful outside of the classroom. “That’s something that AI is really good at.”

The district is one of many across Maine that is increasingly using AI in its classrooms. Some, like Yarmouth, have established formal AI guidelines. Others have not. MagicSchool told The Monitor that it has around 8,500 educator accounts active in Maine. This would equate to more than half of the state’s public school teachers, though anyone can sign up for a free educator account.

The state Department of Education does not yet have data on how many teachers or school districts are using AI, but said that based on the level of interest schools have for AI professional development, its use is widespread. The department is conducting a study to better understand how schools are integrating the new technology and hopes to release data next spring, according to a spokesperson.

The use of generative AI — a type of artificial intelligence that generates new text, images or other content, such as the technology used in ChatGPT — is prompting a growing debate in education. Critics see it as a tool that decreases critical thinking and helps students cheat, while advocates see it as a fixture that students must learn how to use ethically.

A majority of teachers across the country are growing familiar with AI for either personal or school use, and suspect that their students are using it widely as well, according to a 2024 study by the Center for Democracy and Technology.

As AI changes come at breakneck speed, leaders are pushing for its controlled use in schools. Roughly half of states have some form of AI guidance in place, according to the Sutherland Institute.

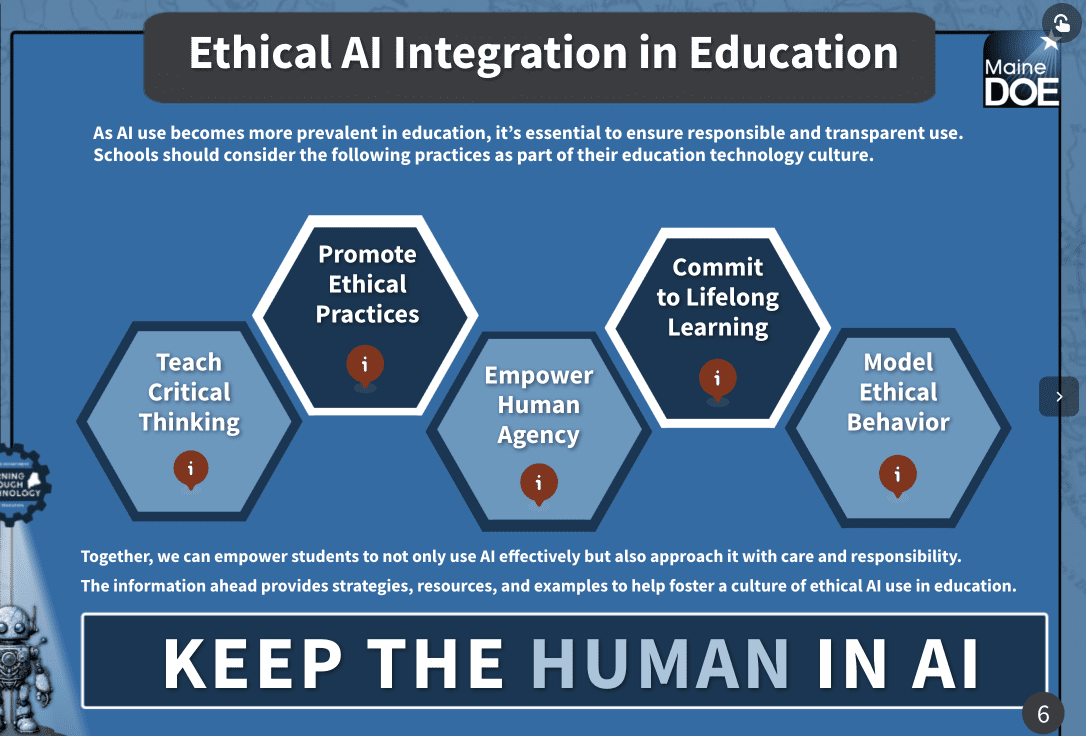

Maine introduced an interactive AI guidance toolkit earlier this year, which walks educators through ways they can integrate AI in the classroom from pre-Kindergarten to 12th grade and the questions to consider when doing so. Students in pre-Kindergarten through second grade could “use AI to generate art and have students collboarate [sic] to create a shared image,” according to the guidance, or high school students could “explore cybersecurity principles through ethical hacking simulations.”

The guidance encourages teachers to “keep the human in AI” by stopping to ask if its use is appropriate for the task, monitoring for accuracy and noting how AI was used.

The governor’s office launched a state AI Task Force last year to prepare Maine for the “opportunities and risks likely to result from advances in AI” in private industries, education and government. The task force’s education subgroup has met three times this year, and plans to release a report on AI use in Maine this fall.

For Yarmouth Superintendent Andrew Dolloff, it is important to help students tackle the increasingly popular technology in a safe environment. The district adopted its first set of AI guidelines last year, which emphasize that staff should be transparent and cite any use of generative AI, ensure student data privacy is protected, be cautious of bias and misinformation and understand the technology “as an evolving tool, not an infallible source.”

“AI is here to stay. It’s part of our lives. We’re all using it as adults on a daily basis. Sometimes without even knowing it or realizing that it’s AI,” Dolloff said. “So we changed our stance pretty quickly to understand that rather than trying to ban AI, we needed to find ways to effectively use it, and allow students to use it appropriately to expand their learning.”

Maine School Administrative District 75 — which serves Harpswell, Topsham, Bowdoin and Bowdoinham — adopted an AI policy earlier this year, though some school board members were hesitant to approve the policy over concerns that generative AI can help students cheat and produce misinformation, The Harpswell Anchor reported.

Some school districts, such as Regional School Unit 22, which serves Hampden, Newburgh, Winterport and Frankfort, have launched internal committees to guide AI use, while others, such as MSAD 15 in Gray and New Gloucester, are pursuing policies in the wake of controversy.

Earlier this year, a student at MSAD 15 alleged that a teacher graded a paper using AI, WGME reported. Superintendent Chanda Turner told The Maine Monitor that teachers are piloting programs that use AI to give feedback on papers, but are not using it to issue grades. The school board will be working on an AI policy for the district this school year, she said.

Nicole Davis, an AI and emerging technology specialist with the DOE who helped write the state guidelines, estimates that over 40 school districts in Maine have requested professional development for AI, and expects that interest will grow. She noted that guiding AI use can be a challenge, as the technology changes so quickly.

“We’re building the plane as we’re flying it,” Davis said.

‘I was stunned’

Julie York, a computer science teacher at South Portland High School, has long incorporated new technology into her teaching, and has found generative AI tools like ChatGPT and Google Gemini to be “incredibly useful.” She has used it to create voiceovers for presentations when she was tired, to help make rubrics and lesson plans and to build a chatbot that can answer questions during class, which she says helps her balance the amount of time she spends with each student.

“I don’t think there’s any educator who wakes up in the morning, and is like, ‘oh my god, I hope I can make a rubric today.’ I just don’t think you’re going to find any,” she said. “And there’s no teacher who isn’t tired.”

She vets all the AI resources she uses before integrating them into her work, and has discussions with her students about when using AI is appropriate. Student use is guided by the traffic light model: if an assignment is green, students can use AI under the guidance of a teacher, if it’s yellow that means limited use with teacher permission, and red means no AI. She makes these determinations depending on the type of assessment. If she wants them to be able to read code and understand what it does, for instance, then AI cannot be used. But if a student is coding a computer program, she said, then AI can be a useful tool.

AI can also help teachers accommodate diverse needs, York said, explaining that students who have trouble speaking in front of a class could use text-to-voice software to produce voiced-over videos. The district’s students speak several different languages, and she used AI to help her create an app that translates her speech into multiple languages while she’s teaching. It took her about an hour to make.

“I just sat there stunned at my computer. Just stunned,” York recalled.

Maine Education Association President Jesse Hargrove said that teachers are exploring the evolving AI landscape alongside their students, noting that AI can help create steps for science projects, or detect whether students cheated.

“I think it’s being used as a partner in the learning, but not a replacement for the thinking,” he said.

MEA’s approach to AI is guided by the National Education Association’s policy, which emphasizes putting educators at the center of education. However, Hargrove said that MEA does not have a stance on whether or not districts should adopt AI.

“We believe that AI should be enhancing the educational experience rather than replacing educators,” he said.

‘Click. Boom. Done.’

Maine’s AI guidance emphasizes that teachers should have clear expectations for AI use in the classroom. It recommends being specific about grade levels, lesson times, content and general student needs when prompting services like ChatGPT to generate lesson plans.

The state told The Monitor it does not recommend any AI tools in particular. Instead, the DOE said it encourages schools to research tools and consider data security, privacy and use.

But its guidance toolkit references a handful of specific programs. MagicSchool and Diffit are listed as tools that can help with accessibility in the classroom. Almanack, MagicSchool and Canva are noted as tools that can help boost student engagement.

The types of AI tools that educators use vary depending on their needs, Davis said, but there seem to be five tools that can assess papers, create study materials and help build curriculums that schools are turning to the most: Diffit, Brisk, Canva, MagicSchool and School AI.

“That batch of essays that’s looming? Brisk will help you grade them before the bell rings,” Brisk’s website reads. “Need a lesson plan for tomorrow? Click. Boom. Done.”

Use of these platforms is regulated by legal parameters for student data safety, such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and Maine’s Student Information Privacy Act. Technology companies must sign a data privacy agreement for the states in which they plan to operate. Maine’s data privacy agreement with MagicSchool, for instance, covers nine other states and sets guardrails for student data collection such as leaving ownership and control of data to “local education agencies.”

Some education-based AI companies also have their own parameters in place. MagicSchool, which was founded by former educator Adeel Khan, requires teachers to sign a best practices agreement, reminds them not to enter personal student information into AI prompts like an Individual Education Plan generator, and claims it erases any student information that gets entered into its system.

“We’re always iterating and trying to make things safer as we go,” Khan said, citing MagicSchool’s favorable rating for privacy on Common Sense Media, an organization that rates technology and digital media for children.

The federal government has also pushed for the use of AI in schools. In the spring, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to promote AI in education, and the federal Department of Education has since published a letter encouraging the use of grant funding to “support improved outcomes for learners through responsible integration of artificial intelligence.”

In late August, First Lady Melania Trump launched the Presidential AI Challenge: asking students to “create AI-based innovative solutions to community challenges.”

The White House is also running a pledge campaign, “Investing in AI Education,” asking technology companies to commit resources like funding, education materials, technology, professional development programs and access to technical expertise to K-12 students, teachers and families for the next four years. More than 100 entities have signed on, including MagicSchool.

In Maine, the DOE is working on broader AI professional development for teachers, with plans to launch a pilot course based on the state’s AI guidance toolkit, potentially as soon as this fall.

As Yarmouth starts the new school year, Arsenault said that AI should be integrated with the goal of preparing students for a future that will be filled with AI.

“We can do what many schools do and ignore it, or we can address it,” Arsenault said. “And if we address it with our students, we have the ability to frame the discussion on how it’s used, and have discussions with our students about how we want to see it used in our classrooms.”

Education

‘I regret pushing my daughter into school until she broke’

Ben SchofieldPolitics correspondent, BBC East

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCThe start of the school year saw the Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson warn parents about the need for children to attend classes.

Data suggests half of pupils who missed lessons in the first week of term last year went on to become persistently absent.

But school leaders say they are seeing more children who find attending school too traumatic.

What is it like having a child with what psychologists call emotionally based school avoidance and what should be done to help?

Family handout

Family handoutThe final time Julie took her daughter to school in July 2023, a member of staff congratulated her.

Rosie, who was then eight, was “wearing a dirty pyjama top, a pair of jogging bottoms, a pair of trainers with no socks, she had her headphones on, she was holding a teddy”, Julie recalls.

“I walked into school and the [special needs co-ordinator] then said to me ‘well done, you got her here’.”

But for Julie, 48, it was not a “win”.

“She couldn’t even speak, she hadn’t eaten, she had maybe three or four hours sleep.

“But I’d done a good job as a parent for making her go to school?”

Family handout

Family handoutAt the time Rosie, who has autism, was in Year Three at a primary school in Northamptonshire.

Julie says her daughter had struggled with the school environment since her time in nursery and is now educated out of school.

Rosie, she recalls, was “in fight and flight the whole time” she was in the classroom, which “just overwhelmed her”.

Eventually Rosie was “begging not to leave” the house for school and was self-harming, sometimes on the school run.

“She would have night terrors – she would be up screaming, if she went to sleep at all.

“It just felt as if I was walking her into the lion’s den every single day,” she says.

Meanwhile, Julie and her husband James received letters and home visits from school staff about Rosie’s attendance.

“It was very lonely.

“All of a sudden there’s these letters and people are talking about fines and I was lost.”

On that final say Julie says she “dragged” Rosie to school because “that was the expectation”.

Now she wishes she had taken Rosie out of school earlier.

“But I also feel that if I hadn’t have got to the point… where she broke, I would never have known if it had worked,” she says.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCBased on Rosie’s reaction to school, an educational psychologist who assessed her noted she had “emotionally based school avoidance” or EBSA, a condition school leaders say they are encountering more.

Anna Hewes, the head teacher of Prince William School, a 1,400-pupil secondary in Oundle, Northamptonshire, says schools are seeing a “big increase” in EBSA among pupils in Year Seven, Eight and Nine.

The transition to secondary school is, she adds, a “key time” and at the start of the school year EBSA is “at the forefront of our minds because of the new year sevens coming through”.

The “noises, the bustling nature of a school – the busyness, all the classes walking around” make it a “real challenge” for those with sensory needs, she says.

But more generally “it’s very tough to be a teenager these days”.

Smartphones and social media, she adds, mean “young people can’t escape anymore”.

“It definitely is a post-Covid spike and these young people are genuinely really struggling to step over the threshold of the school and sometimes leave their bedrooms.”

DJ McLaren/BBC

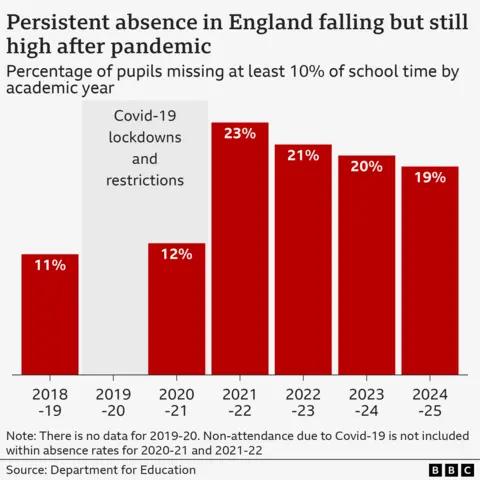

DJ McLaren/BBCAcross England, rates of “persistent absence” – when pupils miss 10% or more of lessons – have remained high since the pandemic.

Last academic year almost 19% of pupils were persistently absent, compared with 11% in 2018/19.

Mrs Hewes says EBSA is a “significant part” of the issue.

A lack of reliable data, however, means it is difficult to know how big a part.

Mrs Hewes says Prince William Academy prioritises “inclusion” and has recruited an assistant head teacher for “belonging”.

It has also opened a specialist “school-within-a-school” for pupils with EBSA, funded by North Northamptonshire Council. Four students have been enrolled so far and by 2028 it expects to see 48.

Jenny Nimmo, the head of inclusion at East Midlands Academy Trust, which runs Prince William Academy, says the unit will have more “homely” classrooms and on-site mental health provision.

She hopes it will be “future proof” because EBSA “isn’t going away”.

There are, she adds, “more and more young people” with “emotionally based school avoidance and indeed anxiety”.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCThe Compass Centre in Luton also help pupils with EBSA access education.

Dr Joanne Summers, Luton Borough Council’s principal educational psychologist, says the condition can appear suddenly but “when you look back, there has been anxiety around being in school” and one incident might be a “catalyst”.

Intervening early, she adds, is important, as falling behind on school work and losing contact with friends can make anxiety worse.

Dr Summers says Luton has been trying to move away from seeing school absences as “defiance and truancy”.

“We are being curious about what’s going on for that young person, why is it that they are behaving in this way,” she adds.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCGeoff Barton, a former head teacher in Suffolk and previous general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, says there should be more “emphasis on the humanity of our schools” rather than “draconian discipline” over absences.

He is researching special educational needs (Send) provision for the left-leaning think tank the Institute for Public Policy Research.

He says the people he is speaking to are “universally saying” that anxiety among pupils has increased.

But the “age of anxiety” is only one reason for persistent absence.

Another is poverty, while he says there is also a “long shadow in education of Covid” when “schools started to feel a bit more of an optional decision”.

Cornelia Andrecut, the executive director of children’s services for North Northamptonshire Council, said the authority has offered training courses for schools to learn strategies to support children with EBSA.

The government says it will spend £740m creating “more specialist places in mainstream schools” and placing Send leads in 1,000 new family hubs.

A Department for Education spokesperson says: “Schools should take a ‘support first’ approach for children who are facing barriers to regular school attendance, and we are expanding access to mental health support teams in all schools, ensuring that every pupil has access to early support services in their community.”

Family handout

Family handoutFor Julie, taking Rosie out of school was “not a lifestyle choice” but was prompted by “trauma and distress” that her daughter is still recovering from.

Does she regret pushing Rosie to attend school?

“Yeah – definitely.

“I always wonder if there was a bit of trust broken between us as mum and daughter when I still took her into that place when it was that bad.”

Education

Earl Richardson, who spotlighted HBCU funding disparities, dies : NPR

Earl Richardson was the president of Morgan State University between 1984 and 2010.

Morgan State University

hide caption

toggle caption

Morgan State University

Earl Richardson was a Black college president — “armed with history,” as a colleague described him — when he led a 15-year-long lawsuit that ended in a historic settlement for four Black schools in Maryland and put a spotlight on funding disparities for all of the nation’s historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

Richardson’s death, at 81, was announced on Saturday by Morgan State University, located in Baltimore, where he served as president when he helped organize the lawsuit that began in 2006. It was settled in 2021 when the state of Maryland agreed to give $577 million in supplemental funding over 10 years to four HBCUs.

Richardson led Morgan State from 1984 to 2010 and he had long chafed at stretching the little funding he got from the state. In the lawsuit, plaintiffs argued that Maryland had historically underfunded its Black colleges and had put them at a disadvantage by starting and boosting similar programs at nearby majority-white schools.

David Burton, one of the plaintiffs, told NPR that the case was compared to Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark lawsuit that brought up similar issues of disparities in educational opportunities for Black students, but the Maryland case raised the issues for students in higher education.

In 1990, when Richardson was a new school president, students took over the administration building for six days to protest the school’s dilapidated classrooms and dorms, with roofs that leaked and science labs stocked with outdated equipment.

Edwin Johnson was one of those student protesters. “We originally were protesting against Morgan’s administration,” including Richardson, he said. “But then after we dig and do a little research, we find out it’s not our administration, but it’s the governor down in Annapolis that isn’t equipping the administration with what they need to appropriately run the school.”

The protest ended when the students marched 34 miles to Annapolis to demand a meeting with the governor.

Richardson, who spoke of taking part in civil rights demonstrations when he was in school, had subtly guided the students to the correct target, said Johnson, who is now the university’s historian and special assistant to the provost.

That protest helped pave the way to the future, historic lawsuit.

Because Richardson was the university’s president, and an employee of the state, he couldn’t sue the state. So, a coalition of students and former students was created, the Coalition for Equity and Excellence in Maryland Higher Education Inc., to serve as the plaintiff.

Still, Richardson was the visionary behind the lawsuit, said Burton, a Morgan State alumnus and now a strategic planner for businesses. “He was armed with history,” Burton said.

“Dr. Richardson knew where the skeletons were,” Burton added. He was “a force that the state could not reckon with because of his institutional knowledge.”

At one point, during the trial, state attorneys objected to Richardson’s presence in the courtroom and asked the judge to make him leave, even though he had a right to be there as an expert witness, said Jon Greenbaum, then the chief counsel of the Lawyer’s Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, who helped argue the lawsuit.

Richardson stayed in the courtroom and “because this was really a desegregation case,” said Greenbaum, he provided historical detail that became critical to the arguments made by the lawyers representing the plaintiffs.

The funding that resulted, and Richardson’s leadership, jump-started what is now called on campus “Morgan’s Renaissance.” Or sometimes, said Johnson: “Richardson’s Renaissance” — because during Richardson’s presidency, enrollment doubled, the campus expanded with new buildings and new schools were added, including a school of architecture and a school of social work.

Richardson’s work put a spotlight, too, on the funding disparities faced by HBCUs across the country. They are more likely than other schools to rely upon federal, state and local funding — money that has faced budget cuts in recent years. Compared to other universities and colleges, HBCUs get a higher percentage of their revenue from tuition and less from private gifts and grants, according to one study.

In testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives in 2008, Richardson emphasized the mission of HBCUs when he told lawmakers that Black schools like his educated the most talented Black students but also sought to attract students who didn’t consider, or thought they couldn’t afford, to go to college. “We can make them the scientists and the engineers and the teachers and the professors — all of those things,” he said. But only if “we can have our institutions develop to a level of comparability and parity so that we are as competitive as other institutions.”

Education

How millions of dollars in funding cuts will impact Hispanic Serving Institutions

Chancellor Sonya Christian of the California Community College system talks about the impact of funding cuts for students.

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms1 month ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Funding & Business3 months ago

Funding & Business3 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries