AI Research

Hundreds of wildfires sparked by ‘live-fire’ military manoeuvres

Malcolm PriorRural affairs producer

BBC

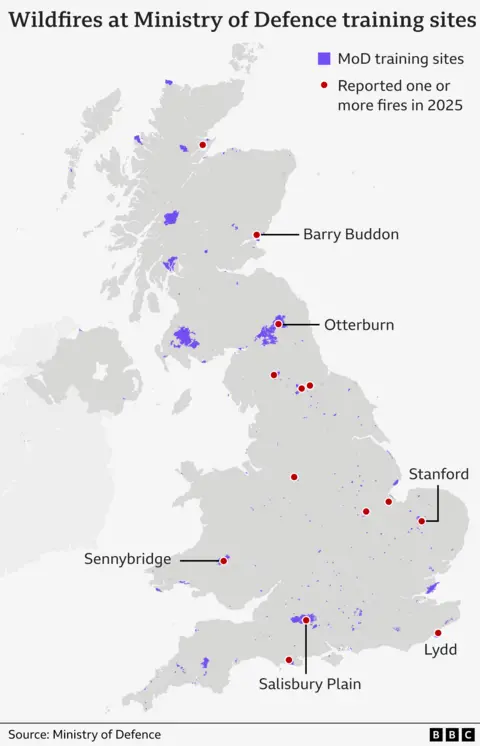

BBCLive-fire military training has sparked hundreds of wildfires across the UK countryside since 2023, with unexploded shells often making it too dangerous to tackle them.

Fire crews battling a vast moorland blaze in North Yorkshire this month have been hampered by exploding bombs and tank shells dating back to training on the moors during the Second World War.

Figures obtained by the BBC show that of the 439 wildfires on Ministry of Defence (MoD) land between January 2023 and last month, 385 were caused by present-day army manoeuvres themselves.

The MoD said it has a robust wildfire policy which monitors risk levels and limits live ammunition use when necessary.

HIWFRS

HIWFRSBut locals near the sites of recent fires told the BBC they felt the MoD needed to do more to prevent them, including completely banning live fire training in the driest months.

Wildfires in the countryside can start for many reasons, including discarded cigarettes, unattended campfires and BBQs and deliberate arson, and the scale of them can be made worse by dry, hot conditions and the amount of vegetation on the land.

But according to data obtained by the BBC under the Freedom of Information Act, there have been 1,178 wildfires in total linked to present-day MoD training sites since 2020 – with 101 out of 134 wildfires in the first six months of this year caused by military manoeuvres or training.

More than 80 of the fires caused by training itself so far this year have been in so-called “Range Danger Areas” – also known as “impact zones”.

These are areas where the level of danger means the local fire service is usually not allowed access and the fire is left to burn out on its own, albeit contained by firebreaks.

The large amounts of smoke produced can lead to road closures, disruption and health risks to local residents, who are directed to keep their windows shut despite it often being the hottest time of the year.

One villager who lives near the MoD’s training site on Salisbury Plain said wildfires there, like the recent one in May, were “a perennial problem” and the MoD had to do more to control them and restrict the use of live ordnance to outside of the hottest months.

Neil Lockhart, from Great Cheverell, near Devizes in Wiltshire, said the smoke from fires left to burn was a major environmental issue and posed a risk to the health and safety of locals.

“It’s the pollution. If you suffer like I do with asthma, and it’s the height of the summer and you’ve got to keep all your windows closed, then it’s an issue,” explained Mr Lockhart.

Arable farmer Tim Daw, whose land at All Cannings overlooks the MoD training site on Salisbury Plain, said he “must have seen three or four big fires this year” but found the smoke only a “mild annoyance”.

He said many locals were worried about the impact of the wildfires on wildlife and the landscape, saying the extent of the area affected by the blazes often looked “fairly horrendous”, and likened it to a “burnt savannah”.

But he said the MoD was “very proactive” in keeping locals informed about the risks of wildfires and any ongoing problems on their land.

Wartime “legacy”

Aside from the problem of live military training sparking fires, old unexploded ordnance left behind from previous manoeuvres make wildfires harder to fight,

This month has seen a major fire burning on Langdale Moor, in the North York Moors National Park, since Monday, 11 August.

It has seen a number of bombs explode in areas that were once used for military training dating back to the Second World War.

One local landowner, George Winn-Darley, said the peat fire had produced “an enormous cloud of pollution” that could have been prevented if there had not been live ordnance on site.

“If that unexploded ordnance had been cleared up and wasn’t there then this wildfire would have been able to be dealt with, probably completely, nearly two weeks ago,” he told the BBC.

Mr Winn-Darley called for the MoD to clear up any major munitions left on the moors.

“That would seem to be the absolute minimum that they should be doing,” he said.

“It seems ridiculous that here we are, 80 years after the end of the Second World War, and we’re still dealing with this legacy.”

A MoD spokesperson said the fire at Langdale had not started on land currently owned by the MoD but that an Army Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) team had responded on four occasions to requests for assistance from North Yorkshire Police.

“Various Second World War-era unexploded ordnance items were discovered as a result of the wildfires, which the EOD operator declared to be inert practice projectiles. They were retrieved for subsequent disposal,” he explained.

He added that the MoD monitors the risk of fires across its training estate throughout the year and restricts the use of ordnance, munitions and explosives when training is taking place during periods of elevated wildfire risk.

“Impact areas” are constructed with fire breaks, such as stone tracks, around them to prevent the wider spread of fire and grazing is used to keep the amount of combustible vegetation down.

Earlier this month, the MoD launched its “Respect the Range” campaign, designed to raise the public’s awareness of the dangers of accessing military land, such as live firing, unexploded ordnance and wildfires.

A spokeswoman for the National Fire Chiefs Council (NFCC) said it worked closely with the MoD to “understand the risk and locations of munitions and to create plans to effectively extinguish fires”.

“We always encourage military colleagues to account for the conditions and the potential for wildfire when considering when to carry out their training,” she added.

AI Research

Physicians Lose Cancer Detection Skills After Using Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence shows great promise in helping physicians improve both their diagnostic accuracy of important patient conditions. In the realm of gastroenterology, AI has been shown to help human physicians better detect small polyps (adenomas) during colonoscopy. Although adenomas are not yet cancerous, they are at risk for turning into cancer. Thus, early detection and removal of adenomas during routine colonoscopy can reduce patient risk of developing future colon cancers.

But as physicians become more accustomed to AI assistance, what happens when they no longer have access to AI support? A recent European study has shown that physicians’ skills in detecting adenomas can deteriorate significantly after they become reliant on AI.

The European researchers tracked the results of over 1400 colonoscopies performed in four different medical centers. They measured the adenoma detection rate (ADR) for physicians working normally without AI vs. those who used AI to help them detect adenomas during the procedure. In addition, they also tracked the ADR of the physicians who had used AI regularly for three months, then resumed performing colonoscopies without AI assistance.

The researchers found that the ADR before AI assistance was 28% and with AI assistance was 28.4%. (This was a slight increase, but not statistically significant.) However, when physicians accustomed to AI assistance ceased using AI, their ADR fell significantly to 22.4%. Assuming the patients in the various study groups were medically similar, that suggests that physicians accustomed to AI support might miss over a fifth of adenomas without computer assistance!

This is the first published example of so-called medical “deskilling” caused by routine use of AI. The study authors summarized their findings as follows: “We assume that continuous exposure to decision support systems such as AI might lead to the natural human tendency to over-rely on their recommendations, leading to clinicians becoming less motivated, less focused, and less responsible when making cognitive decisions without AI assistance.”

Consider the following non-medical analogy: Suppose self-driving car technology advanced to the point that cars could safely decide when to accelerate, brake, turn, change lanes, and avoid sudden unexpected obstacles. If you relied on self-driving technology for several months, then suddenly had to drive without AI assistance, would you lose some of your driving skills?

Although this particular study took place in the field of gastroenterology, I would not be surprised if we eventually learn of similar AI-related deskilling in other branches of medicine, such as radiology. At present, radiologists do not routinely use AI while reading mammograms to detect early breast cancers. But when AI becomes approved for routine use, I can imagine that human radiologists could succumb to a similar performance loss if they were suddenly required to work without AI support.

I anticipate more studies will be performed to investigate the issue of deskilling across multiple medical specialties. Physicians, policymakers, and the general public will want to ask the following questions:

1) As AI becomes more routinely adopted, how are we tracking patient outcomes (and physician error rates) before AI, after routine AI use, and whenever AI is discontinued?

2) How long does the deskilling effect last? What methods can help physicians minimize deskilling, and/or recover lost skills most quickly?

3) Can AI be implemented in medical practice in a way that augments physician capabilities without deskilling?

Deskilling is not always bad. My 6th grade schoolteacher kept telling us that we needed to learn long division because we wouldn’t always have a calculator with us. But because of the ubiquity of smartphones and spreadsheets, I haven’t done long division with pencil and paper in decades!

I do not see AI completely replacing human physicians, at least not for several years. Thus, it will be incumbent on the technology and medical communities to discover and develop best practices that optimize patient outcomes without endangering patients through deskilling. This will be one of the many interesting and important challenges facing physicians in the era of AI.

AI Research

AI exposes 1,000+ fake science journals

A team of computer scientists led by the University of Colorado Boulder has developed a new artificial intelligence platform that automatically seeks out “questionable” scientific journals.

The study, published Aug. 27 in the journal “Science Advances,” tackles an alarming trend in the world of research.

Daniel Acuña, lead author of the study and associate professor in the Department of Computer Science, gets a reminder of that several times a week in his email inbox: These spam messages come from people who purport to be editors at scientific journals, usually ones Acuña has never heard of, and offer to publish his papers — for a hefty fee.

Such publications are sometimes referred to as “predatory” journals. They target scientists, convincing them to pay hundreds or even thousands of dollars to publish their research without proper vetting.

“There has been a growing effort among scientists and organizations to vet these journals,” Acuña said. “But it’s like whack-a-mole. You catch one, and then another appears, usually from the same company. They just create a new website and come up with a new name.”

His group’s new AI tool automatically screens scientific journals, evaluating their websites and other online data for certain criteria: Do the journals have an editorial board featuring established researchers? Do their websites contain a lot of grammatical errors?

Acuña emphasizes that the tool isn’t perfect. Ultimately, he thinks human experts, not machines, should make the final call on whether a journal is reputable.

But in an era when prominent figures are questioning the legitimacy of science, stopping the spread of questionable publications has become more important than ever before, he said.

“In science, you don’t start from scratch. You build on top of the research of others,” Acuña said. “So if the foundation of that tower crumbles, then the entire thing collapses.”

The shake down

When scientists submit a new study to a reputable publication, that study usually undergoes a practice called peer review. Outside experts read the study and evaluate it for quality — or, at least, that’s the goal.

A growing number of companies have sought to circumvent that process to turn a profit. In 2009, Jeffrey Beall, a librarian at CU Denver, coined the phrase “predatory” journals to describe these publications.

Often, they target researchers outside of the United States and Europe, such as in China, India and Iran — countries where scientific institutions may be young, and the pressure and incentives for researchers to publish are high.

“They will say, ‘If you pay $500 or $1,000, we will review your paper,'” Acuña said. “In reality, they don’t provide any service. They just take the PDF and post it on their website.”

A few different groups have sought to curb the practice. Among them is a nonprofit organization called the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). Since 2003, volunteers at the DOAJ have flagged thousands of journals as suspicious based on six criteria. (Reputable publications, for example, tend to include a detailed description of their peer review policies on their websites.)

But keeping pace with the spread of those publications has been daunting for humans.

To speed up the process, Acuña and his colleagues turned to AI. The team trained its system using the DOAJ’s data, then asked the AI to sift through a list of nearly 15,200 open-access journals on the internet.

Among those journals, the AI initially flagged more than 1,400 as potentially problematic.

Acuña and his colleagues asked human experts to review a subset of the suspicious journals. The AI made mistakes, according to the humans, flagging an estimated 350 publications as questionable when they were likely legitimate. That still left more than 1,000 journals that the researchers identified as questionable.

“I think this should be used as a helper to prescreen large numbers of journals,” he said. “But human professionals should do the final analysis.”

A firewall for science

Acuña added that the researchers didn’t want their system to be a “black box” like some other AI platforms.

“With ChatGPT, for example, you often don’t understand why it’s suggesting something,” Acuña said. “We tried to make ours as interpretable as possible.”

The team discovered, for example, that questionable journals published an unusually high number of articles. They also included authors with a larger number of affiliations than more legitimate journals, and authors who cited their own research, rather than the research of other scientists, to an unusually high level.

The new AI system isn’t publicly accessible, but the researchers hope to make it available to universities and publishing companies soon. Acuña sees the tool as one way that researchers can protect their fields from bad data — what he calls a “firewall for science.”

“As a computer scientist, I often give the example of when a new smartphone comes out,” he said. “We know the phone’s software will have flaws, and we expect bug fixes to come in the future. We should probably do the same with science.”

Co-authors on the study included Han Zhuang at the Eastern Institute of Technology in China and Lizheng Liang at Syracuse University in the United States.

AI Research

The Artificial Intelligence Is In Your Home, Office And The IRS Edition

Have you used artificial intelligence (AI) today? Chances are that you have—even if you didn’t realize it. AI is showing up in all aspects of our daily lives, from virtual assistants like Siri or Google Assistant to personalized recommendations (my Spotify DJ is playing as I write this newsletter). You’ve likely used AI through autocorrect and predictive text, as well as spam filters in email—and you may have even used it for your personal financial and tax services.

Companies are also turning to AI. Bain & Company, a global consultancy firm, recently reported that generative AI has become a business staple, with 95% of companies in the U.S. giving it a whirl—a 12% increase in just over a year.

This isn’t just a private sector trend—it’s happening across both public and private sectors and in all industries. Danny Werfel, strategic advisory board member at alliant and former IRS Commissioner, says that more companies are committing to spending money to support AI infrastructure and more leaders asking about how they can effectively integrate AI into their overall corporate strategy. And, Werfel says, it’s no different in the tax space. Technology is increasingly playing a significant role in tax and accounting firms—and at the IRS.

Werfel knows a bit about the use of technology at the IRS, having served as Commissioner from 2023 to 2025. Werfel arrived after the 2022 tax season, which was, to say the least, a challenge. The federal agency was still recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, which had caused delays in the tax filing season. There was a backlog of unfiled returns, and with many offices still not operating at full capacity, securing an in-person appointment was difficult—and reaching a real person on the phone was almost impossible.

There was a bright spot: Those issues gave the agency an opportunity to ramp up the use of technology as a solution. IRS first dipped its toes into AI with its call centers before expanding to chatbots and other ways to assist taxpayers, including detecting scams targeting taxpayers.

“AI,” Werfel says, “is an opportunity and a risk.”

Scammers aren’t just targeting taxpayers. According to a recent study by the Federal Trade Commission, more than half of those who reported losing money to scams or fraud in 2024 were under the age of 19, with $55 million in losses. A smaller percentage of younger adults (44%) reported being a victim of a scam or fraud, but the overall amount of losses was higher—those individuals aged 20 to 29 reported losses of $430 million.

(Overall, younger people report losing money to fraud more often than older people, but the median amount of loss for seniors is much higher.)

What makes younger people vulnerable? Technology plays a big part. Today’s kids are more digitally active than ever, which makes them more vulnerable to online scams. And for students just starting college or heading back to school, it’s often the first time they’re dipping their toes into the real world and managing their own money. Those looking for a good deal on textbooks or an apartment to rent can easily fall into a scammer’s trap.

Darius Kingsley, the Head of Consumer Banking Practices at Chase, highlighted a few of these scams currently making the rounds with some tips on how students and families can protect themselves.

And it’s not just back-to-school season that’s beginning—football season is also on the way. I’m sure that you’ve seen the big football news this week… No, not Travis Kelce’s engagement to Taylor Swift. The other big move. Micah Parsons, who, after demanding a trade from the Dallas Cowboys (located in a jurisdiction with no state income tax), was traded to the Green Bay Packers (located in a jurisdiction with one of the highest state income tax rates) with a reported $188 million contract. He’ll likely now pay millions more annually in state income taxes—he might also have an opportunity to pick up some championship hardware.

(Despite not winning a championship in, well, decades, Dallas remains firmly at the top of the Forbes list of The NFL’s Most Valuable NFL Teams 2025 with an eye-popping $13 billion valuation.)

As for Parsons, I’m not sure how you fit that many zeros on a Form W-2, but I’m guessing we’d all like to try.

We’ll all get a look at a different Form W-2 soon—but not as soon as we thought. The IRS has released drafts of some 2026 tax forms, including a draft of Form W-2. The changes are intended to address tax reporting updates, particularly for employees who receive tips and overtime pay. Notably, the draft Form W-2 is for the 2026 tax year—that’s for the tax return that you’ll file in early 2027. There will be no changes to Form W-2 for the tax year 2025, even though some of the new provisions, including those new, temporary deductions, take effect in 2025. The IRS has previously said that the omissions are “intended to avoid disruptions during the tax filing season and to give the IRS, business and tax professionals enough time to implement the changes effectively.” You can see what the revised draft form looks like and learn more about the changes here (spoiler alert: it’s mostly box code changes).

There’s lots more good information below, including a reminder about alimony and a look at how private equity could be moving into your retirement accounts.

Before I sign off, a special shout out to those of you who finished up your first week of classes–amazing work! If you’re feeling overwhelmed, it will get better, I promise! And for those of you who are first-gen college or university students, I’ve been there–you’ve got this!

Everybody else? Enjoy your long weekend,

Kelly Phillips Erb (Senior Writer, Tax)

Questions

A divorce can impact your taxes—but the timing matters.

getty

This week, a reader asks:

I know that the alimony tax law changed in 2018. Did the new tax law change it back to the old rules?

You’re referring to changes to the tax treatment of alimony. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) did change the alimony rules, making them permanent. However, they were not impacted by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA).

Here’s what changed under the TCJA. For decades, alimony payments were deductible to the payer, even for taxpayers who didn’t itemize, and taxable to the recipient. However, under the TCJA, alimony is no longer deductible under new divorce or separation agreements signed on or after January 1, 2019. That also means that the receipt of alimony is not taxable (under the same conditions).

Agreements signed on or before December 31, 2018, follow the pre-TCJA rules unless you modify the agreement after January 1, 2019, and explicitly reference the change in the law.

You still have to meet some criteria. For example, to qualify as alimony for federal income tax purposes, you must be divorced or under a separation agreement. You cannot be living under the same roof as your spouse/ex-spouse when you make the payments—unless you meet a court-ordered exception—nor can you claim alimony in a year that you file a joint tax return with your spouse/soon-to-be-ex-spouse.

The alimony has to be couched as such–an example includes an official decree of divorce with mandatory support payments, a written separation agreement requiring such payments, or any other type of court order requiring you to support your spouse. The agreement or order does not have to be permanent: temporary decrees, interlocutory (not final) decrees, decrees of alimony pendente lite (awaiting a final decree “during the proceedings”) count.

Alimony payments must be in cash or a cash equivalent, like a check or money order. Property settlements don’t count. And you must not have an obligation to make any payment (in cash or property) after the death of your spouse or former spouse.

The obligation to pay alimony must not be voluntary. The IRS and you may have different understandings of what constitutes “voluntary.” Here’s a tip: if you have an official order or agreement, it’s not voluntary. But if you have an understanding, you feel morally compelled to make payments because you screwed things up or your ex-spouse is demanding that you pay something and just want to shut him or her up, that is voluntary and doesn’t count as alimony.

Finally, alimony payments do not include child support. Child support is tax-neutral—it’s neither tax-deductible to the payer nor taxed as income to the recipient.

–

Do you have a tax question that you think we should cover in the next newsletter? We’d love to help if we can. Check out our guidelines and submit a question here.

Statistics, Charts, and Graphs

Earlier this month, President Trump signed an executive order that could pave the way for the use of private equity (PE) in retirement savings accounts. While private equity isn’t technically prohibited in retirement plans, the associated risks have traditionally given fiduciaries pause.

For many workers, retirement accounts represent most of their liquid savings. At the end of 2024, according to the Investment Company Institute, Americans held $15.2 trillion in individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and another $12.4 trillion in workplace defined contribution plans such as 401(k), 403(b), and 457 plans.

U.S. persons are increasingly saving for retirement.

Kelly Phillips Erb

The incentive to sock money inside retirement accounts instead of, say, a plain vanilla brokerage account is generally tied to tax breaks. Depending on the kind of retirement account, the tax benefits can be immediate, deferred, or both.

Here’s a quick primer: With a traditional IRA, you make potentially tax-deductible contributions. Any earnings, including interest and gains, aren’t taxed until you withdraw from the account once you retire. If you opt for a Roth IRA, contributions are not tax-deductible and are funded with after-tax dollars, but the payoff is that future withdrawals are tax-free.

Your employer may offer a defined contribution plan like a 401(k), 403(b), governmental 457 plans, and the federal government’s Thrift Savings Plan. With an employer-sponsored retirement account, you can kick in a portion of your paycheck toward retirement savings (typically, pre-tax contributions) and your employer may offer a matching contribution. There may also be a Roth option for these accounts—as with a Roth IRA, with a Roth 401(k) or similar plan, in exchange for paying taxes upfront, the contributions and earnings can be withdrawn tax-free in retirement.

From a tax standpoint, the benefit of traditional (non-Roth) retirement accounts is generally two-fold: earnings don’t count towards your current year income—which reduces your potential tax bill—and it grows tax-deferred. When you reach retirement age, withdrawals are taxable as you take the money out—certain exceptions may apply.

The Executive Order doesn’t change the rules for retirement plans. It does, however, seek to change the “regulatory burdens and litigation risk” that may currently stand in the way of investing in alternative assets inside retirement plans. Under the Order, alternative assets include not only private equity, but also real estate and other assets like cryptocurrency.

So what makes private equity different from a more traditional investment? In PE, investors target privately held companies, as opposed to publicly held companies. Unlike investing in a public company, investing in a private company typically involves fewer regulations but requires more capital. The finances of private companies may be less transparent and more difficult to interpret. That means that PE isn’t for everyone.

A Deeper Dive

AUSTIN, TEXAS – JULY 17: In this photo illustration, Coke beverages are displayed in an ice-cooler at a park on July 17, 2025 in Austin, Texas. (Photo illustration by Brandon Bell/Getty Images)

Getty Images

Transfer pricing cases look to be the hot tax topic for fall, with several high-profile cases moving through the court system.

Transfer pricing is a tricky concept affecting multinational corporations and how they allocate costs and–ultimately–taxable profits. In a typical scenario, a parent company may set up several subsidiary companies all over the world and move goods, services, and assets from one to another—that’s completely okay. However, transactions between those companies are supposed to be at “arm’s length,” meaning that the goods, services, and assets are transferred for the same price as they would have been between unrelated parties. But often, that’s not what happens.

With a wink and a nudge, transactions are often structured to shift profits from high-tax countries to low-tax countries to cut their tax bills. The most popular target for transfer pricing abuse is intangible property, including licenses for manufacturing, distribution, sale, marketing, and promotion of products in overseas markets. Since intangible property doesn’t really have a physical home—unlike, say, real estate—it’s easy to transfer it to countries that offer certain benefits, including more favorable tax treatment.

Transfer pricing cases are often referred to as section 482 cases. Section 482 of the Tax Code—which has existed since the 1920s—gives the IRS broad authority to make adjustments on returns and allocate the income, deductions, and credits of commonly owned or controlled organizations, entities, or businesses. According to the Treasury, these adjustments are made “to prevent evasion of taxes or to clearly reflect income.”

One of those section 482 cases involves Facebook. The case focused on the value of the platform contribution transaction (PCT) that Facebook’s Irish subsidiary owed the U.S. parent company for the right to participate in this 2010 cost-sharing arrangement, or CSA. The case essentially involved a dispute over the valuation method—which is the most reliable, and how it should be applied? Facebook’s method initially yielded a value of approximately $6.3 billion for the PCT, whereas the IRS, using its own method, arrived at a value of almost $20 billion.

The IRS won and it lost. It won in the sense that Tax Court Judge Cary Pugh upheld the general validity of the income method. However, the IRS lost in the sense that nearly every methodological detail and assumption that went into its income method analysis was rejected. In the end, the Tax Court reduced the PCT from the $20 billion initially proposed by the IRS, all the way down to $7.8 billion, which is much closer to the $6.3 billion that Facebook initially estimated.

Another big transfer pricing case in the news involves Coca-Cola. This case focuses largely on royalties. Coca-Cola has argued that the IRS’s valuation analysis is flawed and that an old closing agreement, which provided for a simple profit allocation formula, should be honored moving forward. That case, which involves billions of dollars, is still being litigated.

(You can read my summary from last year here.)

Two other transfer pricing cases, Medtronic and 3M, are on appeal to the Eighth Circuit. And now, both cases are fully briefed and argued. 3M is about a specific and narrower issue, the validity of the blocked income regulations. Medtronic II is a broader case about the best method and valuation.

You can find out more about all of these cases on the most recent episode of Tax Notes Talk. You can read the transcript here.

Tax Filings And Deadlines

📅 September 15, 2025. Third quarter estimated payments due for individual taxpayers.

📅 September 30, 2025. Due date for individuals and businesses impacted by recent terrorist attacks in Israel.

📅 October 15, 2025. Due date for individuals and businesses affected by wildfires and straight-line winds in southern California that began on January 7, 2025.

📅 November 3, 2025. Due date for individuals and businesses affected by storms in Arkansas and Tennessee that began on April 2, 2025.

Tax Conferences And Events

📅 September 9-September 16 (various dates), 2025. IRS Nationwide Tax Forum in New Orleans, Orlando, Baltimore and San Diego. Registration required (discounts available for some partner groups).

📅 September 17-18, 2025. National Association of Tax Professionals Las Vegas Tax Forum. Paris Hotel, Las Vegas, Nevada. Registration required.

📅 Sept. 26-27, 2025. National Association of Tax Professionals Philadelphia Tax Forum. Sheraton Philadelphia Downtown, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Registration required.

Trivia

When were the first Forms W-2 issued?

(A) 1913

(B) 1944

(C) 1965

(D) 1978

Find the answer at the bottom of this newsletter.

Positions And Guidance

The IRS has published Internal Revenue Bulletin 2025-36.

The IRS announced that interest rates will remain unchanged for the calendar quarter beginning October 1, 2025. For individuals, the rate for overpayments (yes, IRS has to pay you interest sometimes) and underpayments will be 7% per year, compounded daily. The rate is 6% for corporation overpayments (4.5% for the portion of a corporate overpayment exceeding $10,000) and 7% for corporate underpayments (9% for large corporate underpayments). The interest rate is set quarterly—the most recent rates are based on the federal short-term rate determined in July 2025. You can find the details in Rev Ruling 2025-18, which will appear in IRB 2025-37, dated September 8, 2025.

Noteworthy

ICYMI: The IRS is inviting the public to participate in an anonymous feedback survey on tax preparation and filing options. The survey is being conducted as part of the Department of Treasury and the IRS’ efforts to fulfill a reporting requirement to Congress under the new tax law. The survey will run through September 5, 2025.

Hoping to travel this fall? The IRS is urging taxpayers to resolve their significant tax debts to avoid putting their passports in jeopardy. The Taxpayer Advocate has more information.

—

If you have tax and accounting career or industry news, submit it for consideration here or email me directly.

In Case You Missed It

Here’s what readers clicked through most often in the newsletter last week:

You can find the entire newsletter here.

Trivia Answer

The answer is (B).

The Current Tax Payment Act of 1943 introduced pay-as-you-go (which featured withholding)–and Forms W-2 to track it. The first Forms W-2 were issued the following year, in 1944.

The first modern income tax was established in the U.S. in 1913, but that predates third-party reporting.

In 1965, the IRS changed the name of the form to better reflect the information being reported. Instead of “Withholding Tax Statement,” it was changed to “Wage and Tax Statement,” which is what it still says today.

Screenshot of 1978 Form W-2 from IRS website

Kelly Phillips Erb

In 1978, Form W-2 was redesigned to look more modern, including the numbered boxes we’ve grown to know and love.

Feedback

How did we do? We’d love your feedback. If you have a suggestion for making the newsletter better, submit it here or email me directly.

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences3 months ago

Events & Conferences3 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months ago

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months agoDonald Trump suggests US government review subsidies to Elon Musk’s companies

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoAstrophel Aerospace Raises ₹6.84 Crore to Build Reusable Launch Vehicle