AI Research

MIT Artificial Intelligence (AI) report fallout – if AI winter is coming, it can’t arrive soon enough

Back in March, I warned that, despite the blooming AI Spring, an AI winter might soon be upon us, adding that a global reset of expectations was both necessary and overdue.

There are signs this month that it might be beginning: the Financial Times warns this week that AI-related tech shares are taking a battering, including NVIDIA (down 3.5%), Palantir (down 9.4%), and Arm (down five percent), with other stocks following them downwards.

The cause? In part, a critical MIT report, revealing that 95% of enterprise gen AI programs are failing, or return no measurable value. More on that in a moment.

But the absurdity of today’s tech-fueled stock market was revealed by one Financial Times comment:

The tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite closed down 1.4 percent, the biggest one-day drop for the index since 1 August.

That a single-digit one-day drop three weeks after another single-digit drop might constitute a global crisis indicates just how jittery and short-termist investor expectations have become. The implication is that, behind the hype and Chief Executive Officers’ (CEOs) nonsensical claims of Large Language Models’ (LLMs) superintelligence, are thousands of nervous investors biting their lips, knowing that the bubble might burst at any time.

As the Economist notes recently, some AI valuations are “verging on the unhinged”, backed by hype, media hysteria, social media’s e/acc cultists, and the unquestioning support of politicians desperate for an instant source of growth – a future of “infinite productivity”, no less, in the words of UK AI and digital government minister Feryal Clark in the Spring.

Altman’s cynical candor

The tell comes last week from the industry’s leader and by far its biggest problem: OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, a man whose every interview with client podcasters should be watched with the sound off, so you can focus on his body language and smirk, which scream “Everything I’m telling you is probably BS”.

In a moment of atypical – yet cynical – candor, Altman says:

Are investors over excited? My opinion is yes. […] I do think some investors are likely to lose a lot of money, and I don’t want to minimize that, that sucks. There will be periods of irrational exuberance. But, on the whole, the value for society will be huge.

Nothing to see here: just the man who supported the inflated bubble finally acknowledging that the bubble exists, largely because AI has industrialized laziness rather than made us smarter. And this comes only days after the fumbled launch of GPT-5, a product so far removed from artificial general intelligence (AGI) as to be a remedial student. (And remember, AGI – the founding purpose of OpenAI – is no longer “a super-useful term”, according to Altman.)

The sector’s problems are obvious and beg for a global reset. A non-exhaustive list includes:

First, vendors scraped the Web for training data – information that may have been in a public domain (the internet) but which was not always public-domain in terms of rights. As a result, they snapped up copyrighted content of every kind: books, reports, movies, images, music, and more, including entire archives of material and pirate libraries of millions of books.

Soon, the Web was awash with ‘me too’ AIs that, far from curing cancer or solving the world’s most urgent problems, offered humans the effort-free illusion of talent, skill, knowledge, and expertise – largely based on the unauthorized use of intellectual property (IP) – for the price of a monthly subscription.

Suddenly AIs composed songs, wrote books, made videos, and more. This exploitative bilge devalued human skill and talent, and certainly its billable potential, spurring an outcry from the world’s creative sectors. After all, the training data’s authors and rightsholder receive nothing from the deal.

Second, the legal repercussions of all this are just beginning for vendors. Anthropic is facing an existential crisis in the form of a class action by (potentially) every US author whose work was scraped, the plaintiffs allege, from the LibGen pirate library.

Meta is known to have exploited the same resource rather than license that content – according to a federal judge in June – while a report from Denmark’s Rights Alliance in the Spring revealed that other vendors had used pirated data to train their systems.

Is Otter meeting its nemesis?

But word reaches me this week that the legal fallout does not just concern copyright: the first lawsuits are beginning against vendors’ cloud-based tools disclosing private conversations to AIs without the consent of participants. The first player in the spotlight? Our old friend, Otter AI.

Last year I reported how this once-useful transcription tool had become so “infected” with AI functions that it had begun rewriting history and putting words in people’s mouths, flying in data from unknown sources and crediting it to named speakers. As a result, it had become too dangerous to use.

In the US, Otter is now being sued by the plaintiff Justin Brewer (“individually and on behalf of others similarly situated” – a class action) for its Notetaker service disclosing the words of meetings – including of participants who are not Otter subscribers – to its GPT-based AI. Brewer’s conversations were “intercepted” by Otter, the suit alleges.

Clause Three of the action says:

Otter does not obtain prior consent, express or otherwise, of persons who attend meetings where the Otter Notetaker is enabled, prior to Otter recording, accessing, reading, and learning the contents of conversations between Otter account holders and other meeting participants.

Moreover, Otter completely fails to disclose to those who do set up Otter to run on virtual meetings, but who are recorded by the Otter Notetaker, that their conversations are being used to train Otter Notetaker’s automatic speech recognition (ASR) and Machine Learning (ML) models, and in turn, to financially benefit Otter’s business.

Brewer believes that this breaches both federal and California law – namely, the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986; the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act; the California Invasion of Privacy Act; California’s Comprehensive Computer Data and Fraud Access Act; the California common law torts of intrusion upon seclusion and conversion; and the California Unfair Competition Law. That’s quite a list.

Speaking as a journalist, these same problems risk breaching confidentiality when tools like Otter record and transcribe interviews with, for example, CEOs, academics, analysts, spokespeople, and corporate insiders and whistleblowers. Who would consent to an interview if the views of named speakers, expressed in an environment of trust, might be disclosed to AI systems, third-party vendors, and unknown corporate partners, without the journalist’s knowledge – let alone the interviewee’s.

Thanks for speaking to me, Whistleblower X. Do you consent to your revelations being used to train ChatGPT?

The zero-click problem

Third, AI companies walled off all that scraped data and creatives’ IP and began renting it back to us, causing other forms of Web traffic to fall away. As I noted last week, 60% of all Google Web searches are already ‘zero click’, meaning that users never click out to external sources. More and more data is consumed solely within AI search, a trend that can only deepen as Google transitions to AI Mode.

My report added:

Inevitably, millions of websites and trusted information sources will wither and die in the AI onslaught. And we will inch ever closer to the technology becoming what I have long described as a coup on the world’s digitized content – or what Canadian non-profit media organization The Walrus called ‘a heist’ this month.

Thus, we are becoming unmoored from authoritative, verifiable data sources and cast adrift on an ocean of unreliable information, including hallucinations. As I noted in an earlier report this month, there have been at least 150 cases of experienced US lawyers presenting fake AI precedent in court. What other industries are being similarly undermined?

Fourth, as previously documented, some AI vendors’ data center capex is at least an order of magnitude higher than the value of the entire AI software market. As a result, they need others to pay their hardware costs – including, perhaps, nations within new strategic partnerships. Will those sums ever add up?

Then, fifth, there are the energy and water costs associated with training and using data-hungry AI models.

As I have previously noted, cloud data centers already use more energy than the whole of Japan, and AI will force that figure much higher. Meanwhile, in a moment of absurdist comedy, the British Government last week advised citizens to delete old emails and photos because data centers use “vast amounts of water” and risk triggering a drought. A ludicrous announcement from a government that wants to plough billions into new AI facilities.

Sixth, report after report reveals that most employees use AI tactically to save money and time, not strategically to make smarter decisions. So bogus claims of AGI and superintelligence miss the point of enterprises’ real-world usage – much of which is shadow IT, as my report on accountability demonstrated this week.

But seventh, if some people are using AI to make smarter decisions rather than cut corners and save time, several academic reports have revealed that it is having the opposite effect: in many cases, AI is making us dumber, lazier, and less likely to think critically or even retain information. This 206-page study on arXiv examining the cognitive impacts of AI assistance is merely one of example many.

And eighth in our ever-expanding list of problems, AI just isn’t demonstrating a hard Return on Investment (ROI) – either to most users, or to those nervous investors who are sitting on their hands in the bus of survivors (to quote the late David Bowie).

Which brings us back to that MIT Nanda Initiative report, which has so alarmed the stock market – not to mention millions of potential customers. ‘The GenAI Divide: State of AI in Business 2025’ finds that enterprise gen AI programs fall short in a stunning 95% of cases.

Lead author Aditya Challapally explains to Forbes that generic tools like ChatGPT excel for individuals because of their flexibility – other reports find that much ‘enterprise adoption’ is really those individuals’ shadow IT usage – but they stall in enterprise use since they don’t learn from or adapt to workflows.

Forbes adds a note of warning about the employment challenge in many organizations too:

Workforce disruption is already underway, especially in customer support and administrative roles. Rather than mass layoffs, companies are increasingly not backfilling positions as they become vacant.

My take

Taking all these challenges together, we have an alarming picture: overvalued stocks; an industry fueled by absurd levels of cultish hype, spread unquestioningly on social platforms that amplify CEOs’ statements, but never challenge them; rising anger in many communities about industrialized copyright theft and data laundering; absent enterprise ROI; high program failure rates; naïve politicians; soaring energy and water costs; and systems that, while teaching people to ask the right questions, often fail to help them learn the right answers.

Meanwhile, we are told that AI will cure cancer and solve the world’s problems while, somehow, delivering miraculous growth, equality, and productivity. Yet in the real world, it is mainly individuals using ChatGPT to cut corners, generate text and rich media (based on stolen IP), and to transcribe meeting notes – and even that function may prove to be illegal.

Time for a reset. The world needs realism, not cultish enablement.

AI Research

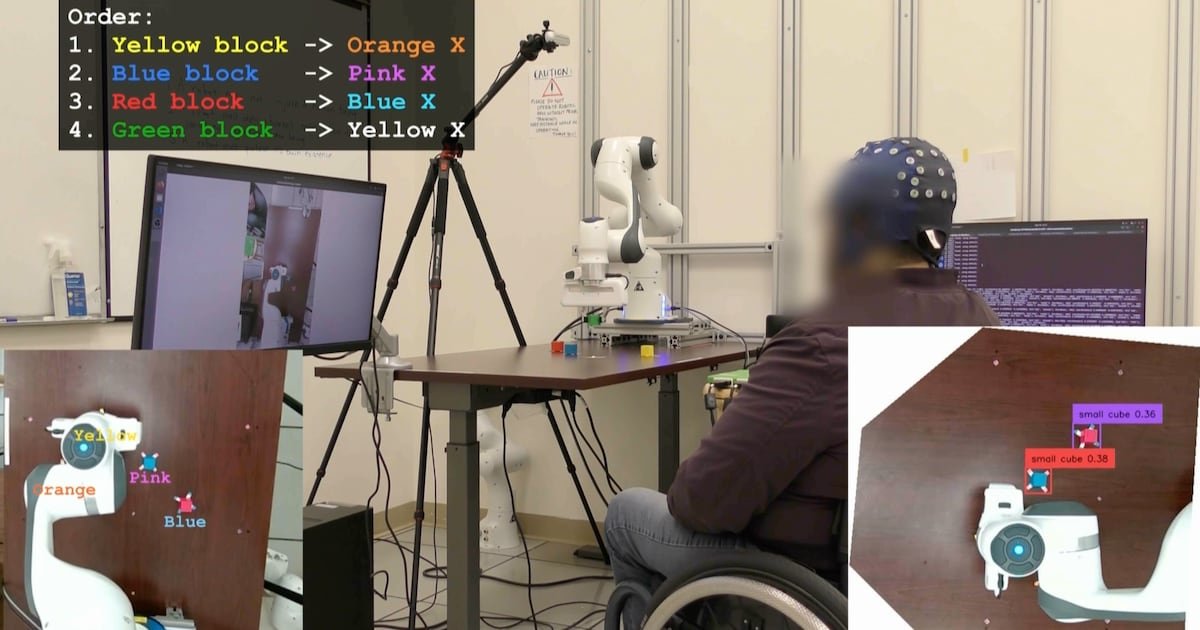

UCLA Researchers Enable Paralyzed Patients to Control Robots with Thoughts Using AI – CHOSUNBIZ – Chosun Biz

AI Research

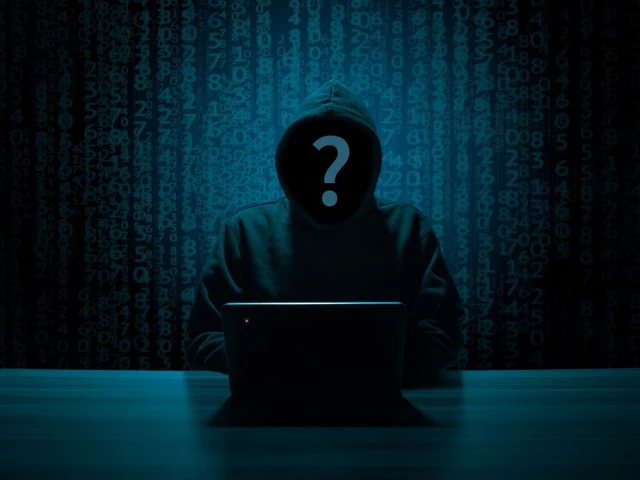

Hackers exploit hidden prompts in AI images, researchers warn

Cybersecurity firm Trail of Bits has revealed a technique that embeds malicious prompts into images processed by large language models (LLMs). The method exploits how AI platforms compress and downscale images for efficiency. While the original files appear harmless, the resizing process introduces visual artifacts that expose concealed instructions, which the model interprets as legitimate user input.

In tests, the researchers demonstrated that such manipulated images could direct AI systems to perform unauthorized actions. One example showed Google Calendar data being siphoned to an external email address without the user’s knowledge. Platforms affected in the trials included Google’s Gemini CLI, Vertex AI Studio, Google Assistant on Android, and Gemini’s web interface.

Read More: Meta curbs AI flirty chats, self-harm talk with teens

The approach builds on earlier academic work from TU Braunschweig in Germany, which identified image scaling as a potential attack surface in machine learning. Trail of Bits expanded on this research, creating “Anamorpher,” an open-source tool that generates malicious images using interpolation techniques such as nearest neighbor, bilinear, and bicubic resampling.

From the user’s perspective, nothing unusual occurs when such an image is uploaded. Yet behind the scenes, the AI system executes hidden commands alongside normal prompts, raising serious concerns about data security and identity theft. Because multimodal models often integrate with calendars, messaging, and workflow tools, the risks extend into sensitive personal and professional domains.

Also Read: Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang says AI boom far from over

Traditional defenses such as firewalls cannot easily detect this type of manipulation. The researchers recommend a combination of layered security, previewing downscaled images, restricting input dimensions, and requiring explicit confirmation for sensitive operations.

“The strongest defense is to implement secure design patterns and systematic safeguards that limit prompt injection, including multimodal attacks,” the Trail of Bits team concluded.

AI Research

When AI Freezes Over | Psychology Today

A phrase I’ve often clung to regarding artificial intelligence is one that is also cloaked in a bit of techno-mystery. And I bet you’ve heard it as part of the lexicon of technology and imagination: “emergent abilities.” It’s common to hear that large language models (LLMs) have these curious “emergent” behaviors that are often coupled with linguistic partners like scaling and complexity. And yes, I’m guilty too.

In AI research, this phrase first took off after a 2022 paper that described how abilities seem to appear suddenly as models scale and tasks that a small model fails at completely, a larger model suddenly handles with ease. One day a model can’t solve math problems, the next day it can. It’s an irresistible story as machines have their own little Archimedean “eureka!” moments. It’s almost as if “intelligence” has suddenly switched on.

But I’m not buying into the sensation, at least not yet. A newer 2025 study suggests we should be more careful. Instead of magical leaps, what we’re seeing looks a lot more like the physics of phase changes.

Ice, Water, and Math

Think about water. At one temperature it’s liquid, at another it’s ice. The molecules don’t become something new—they’re always two hydrogens and an oxygen—but the way they organize shifts dramatically. At the freezing point, hydrogen bonds “loosely set” into a lattice, driven by those fleeting electrical charges on the hydrogen atoms. The result is ice, the same ingredients reorganized into a solid that’s curiously less dense than liquid water. And, yes, there’s even a touch of magic in the science as ice floats. But that magic melts when you learn about Van der Waals forces.

The same kind of shift shows up in LLMs and is often mislabeled as “emergence.” In small models, the easiest strategy is positional, where computation leans on word order and simple statistical shortcuts. It’s an easy trick that works just enough to reduce error. But scale things up by using more parameters and data, and the system reorganizes. The 2025 study by Cui shows that, at a critical threshold, the model shifts into semantic mode and relies on the geometry of meaning in its high-dimensional vector space. It isn’t magic, it’s optimization. Just as water molecules align into a lattice, the model settles into a more stable solution in its mathematical landscape.

The Mirage of “Emergence”

That 2022 paper called these shifts emergent abilities. And yes, tasks like arithmetic or multi-step reasoning can look as though they “switch on.” But the model hasn’t suddenly “understood” arithmetic. What’s happening is that semantic generalization finally outperforms positional shortcuts once scale crosses a threshold. Yes, it’s a mouthful. But happening here is the computational process that is shifting from a simple “word position” in a prompt (like, the cat in the _____) to a complex, hyperdimensional matrix where semantic associations across thousands of dimensions create amazing strength to the computation.

And those sudden jumps? They’re often illusions. On simple pass/fail tests, a model can look stuck at zero until it finally tips over the line and then it seems to leap forward. In reality, it was improving step by step all along. The so-called “light-bulb moment” is really just a quirk of how we measure progress. No emergence, just math.

Why “Emergence” Is So Seductive

Why does the language of “emergence” stick? Because it borrows from biology and philosophy. Life “emerges” from chemistry as consciousness “emerges” from neurons. It makes LLMs sound like they’re undergoing cognitive leaps. Some argue emergence is a hallmark of complex systems, and there’s truth to that. So, to a degree, it does capture the idea of surprising shifts.

But we need to be careful. What’s happening here is still math, not mind. Calling it emergence risks sliding into anthropomorphism, where sudden performance shifts are mistaken for genuine understanding. And it happens all the time.

A Useful Imitation

The 2022 paper gave us the language of “emergence.” The 2025 paper shows that what looks like emergence is really closer to a high-complexity phase change. It’s the same math and the same machinery. At small scales, positional tricks (word sequence) dominate. At large scales, semantic structures (multidimensional linguistic analysis) win out.

No insight, no spark of consciousness. It’s just a system reorganizing under new constraints. And this supports my larger thesis: What we’re witnessing isn’t intelligence at all, but anti-intelligence, a powerful, useful imitation that mimics the surface of cognition without the interior substance that only a human mind offers.

Artificial Intelligence Essential Reads

So the next time you hear about an LLM with “emergent ability,” don’t imagine Archimedes leaping from his bath. Picture water freezing. The same molecules, new structure. The same math, new mode. What looks like insight is just another phase of anti-intelligence that is complex, fascinating, even beautiful in its way, but not to be mistaken for a mind.

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms3 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences3 months ago

Events & Conferences3 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months ago

Mergers & Acquisitions2 months agoDonald Trump suggests US government review subsidies to Elon Musk’s companies

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi