Education

Is there a ‘resit crisis’? Key takeaways from 2025’s GCSE results

BBC Verify

PA

PAMore than 600,000 teenagers have been opening GCSE and other Level 2 results on Thursday.

Most have just finished Year 11, marking the end of a secondary school journey that began in Covid “bubbles” back in 2020.

But a growing proportion of those opening results are older, having resat the English or maths GCSEs that they didn’t pass the first time around.

Many of those older students will have sat their initial GCSEs at a time when grades were being purposefully lowered to tackle grade inflation during the pandemic.

Here are the key things you need to know.

1. GCSE pass rate falls again

The GCSE pass rate has fallen again – with 67.4% of all grades in England, Wales and Northern Ireland at 4/C and above.

That is slightly down from 67.6% last year.

Grades were always expected to be similar to last year, after years of flux because of the Covid pandemic.

There were sharp rises in top grades in 2020 and 2021 when exams were cancelled and results were based on teachers’ assessments.

That was followed by a phased effort to bring them back down to 2019 levels, and grading returned to pre-pandemic standards across all three nations last year.

While the overall pass rate fell this year, there are differences between the nations.

England is the only nation to have seen a fall (from 67.4% to 67.1%). The pass rate has actually gone up in Wales (from 62.2% to 62.5%) and Northern Ireland (from 82.7% to 83.5%).

The percentage of all top grades, marked at 7/A or above, rose very slightly from 21.8% to 21.9%. There have been warnings of fiercer competition for places at sixth form colleges this year.

2. Resit numbers are up

Nearly a quarter of maths and English GCSEs were taken by people aged 17 and older this year.

They made up 23.4% of maths and English grades – compared to 20.9% last year.

Some will be mature students sitting exams for the first time, but most will be young people resitting papers.

Many of them will have taken their GCSEs the first time around when grades were being brought down after the pandemic, leading to fewer passes.

In England, pupils who don’t get at least a grade 4 in GCSE English and maths have to continue studying for it alongside their next course – their A-levels or their T-level, for example.

The Department for Education (DfE) says pupils should retake the exam when they think they are ready – although it has been described as a requirement in the past.

The pass rate for those who resit is far lower than it is for Year 11s.

In England, just 20.9% of English entries and 17.1% of maths entries from people aged 17 and over were marked at grade 4 or higher.

Jill Duffy, the head of the OCR exam board, said there was a “resit crisis”.

“Tinkering at the edges of policy won’t fix this,” she said. “We need fundamental reform to maths and English secondary education… to support those who fall behind.”

The Association of School and College Leaders called the policy “demoralising”, while the Association of Colleges said resits “can undermine confidence and motivation”.

They are all waiting for the DfE to publish its curriculum and assessment review this year, which is examining the policy.

3. Regional gap shrinks, but it’s still higher than before Covid

Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson warned on Wednesday that these GCSE results would “expose the inequalities that are entrenched in our education system”.

We only have limited data at the moment – a breakdown of exam results by things like ethnicity and free school meal status come later in the year – but we can look at regional differences.

Like last year, London had the highest pass rate (71.6%) and the West Midlands had the lowest (62.9%).

It’s the first time the gap between the highest- and lowest-performing regions has shrunk since 2021. It’s 8.7 percentage points this year, down from 9.4 last year.

However, the gap is still wider than it was at any point in the decade leading up to the pandemic, when it ranged between 6.4 and 7.2 percentage points.

The narrowing of the gap this year is not because the pass rate in the West Midlands has risen (it has actually dropped slightly), but rather because it fell more steeply in London than in any other region.

4. Gap between boys and girls is the lowest on record

The gap between boys’ and girls’ pass rates across all three nations has narrowed to its lowest on record.

Girls continue to outperform boys, but their grades have dropped while boys’ have risen slightly.

It means there’s a difference of 6.1 percentage points this year, down from 6.7 last year.

We’ve been looking over data that goes back all the way to 2000, and that gap is the lowest it’s been at any point this century.

It was at its widest in 2017 (9.5 percentage points) and has been falling ever since.

Analysis from the Education Policy Institute suggests that girls’ performance has been “declining in absolute terms” since the Covid pandemic.

It has linked this to “worrying trends around girls’ wellbeing” such as worsening mental health and social media use.

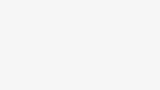

5. Au revoir French… hola Spanish

French has been a staple of British secondary education for years, but it’s been overtaken by Spanish in popularity for the first time ever.

There were 136,871 entries for Spanish GCSE this year, compared to 132,808 for French.

Ms Duffy, from the OCR, said it could be because Spanish was a “massive global language” and Spain was a popular holiday destination.

One French teacher at a school in Scarborough agreed, telling the BBC that pupils associated Spanish with their favourite footballers, as well as “sunshine and holidays”.

“They say they are more likely to use it when they go away,” she said.

The Association of School and College Leaders said it was “great to see” Spanish becoming so popular, but the decline in entries to French and German was a “source of concern”.

Additional reporting by Phil Leake, Libby Rogers, Muskeen Liddar, Daniel Wainwright and Jess Carr.

Education

UM Today | Faculty of Education

September 11, 2025 —

The Digital Literacies Lab in the Faculty of Education, in collaboration with the Media Lab in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Manitoba, presents a hybrid speaker series (in-person and online) that will explore the potential and ethical challenges of generative artificial intelligence technologies in education, and the role of digital literacies in this context.

Through engaging talks and workshop-style discussions, this series aims to foster critical dialogue, inspire innovation, and support educators, researchers, and students in navigating the evolving role of AI in teaching, learning, and educational policy. Join us as we delve into opportunities and complexities of artificial intelligence and the role of digital literacies in education and beyond.

Join in-person viewing in the Digital Literacies Lab (RM 328, Education Building) or the Faculty of Arts Media Lab (233 University College) with post-workshop discussions.

All workshops will be streamed on Zoom, with three of the four presenters joining online. Complete event information for each workshop and registration for online viewing can be found here.

Workshops include:

Sept 23 (6:00pm – 7:30pm) – “Generative AI: Implications and Applications for Education” with Bill Cope & Mary Kalantzis

Oct 21 (6:00pm – 7:30pm) – “The End of the World as We Know It? AI, Post-Literate Society and Education” with Allan Luke

November 25 (6:00pm – 7:30pm) – “Assessment Literacy in the Age of AI” with Michael Holden (in person presentation at 328 Education building)

Dec 2 (6:00pm – 7:30pm) – “Digital Literacies as Literacies of Repair” with Rodney H. Jones

Education

$53B Market Growth by 2030 Amid Benefits and Risks

In the rapidly evolving realm of education technology, artificial intelligence is reshaping how students absorb and retain knowledge, prompting educators and researchers to scrutinize its long-term effects. Recent studies highlight both transformative potential and subtle pitfalls, as AI tools like chatbots and personalized learning platforms become classroom staples. For instance, a Boise State University professor, Jenni Stone, recently explored these dynamics in an article for The Conversation, emphasizing how AI might inadvertently hinder deep learning by providing quick answers that bypass critical thinking.

Stone’s analysis draws on empirical data showing that while AI excels at delivering customized content, it can reduce students’ engagement with complex problem-solving. Her work, published amid a surge of 2025 research, aligns with findings from a Microsoft Education Blog report, which surveyed educators and found that 68% believe AI enhances teaching efficiency but warns of overreliance eroding foundational skills.

Personalized Learning’s Double-Edged Sword

This tension is evident in global trends, where AI-driven adaptive systems tailor lessons to individual paces, potentially boosting outcomes for diverse learners. A study in the journal Education Sciences, conducted at Romania’s National University of Science and Technology POLITEHNICA Bucharest, polled 85 students and revealed that 72% reported improved academic performance through AI tools, yet 45% expressed concerns about diminished critical analysis abilities. The research underscores AI’s role in democratizing education, particularly in underserved regions, by offering real-time feedback that human teachers might not scale.

However, the Bucharest study also flags ethical dilemmas, such as data privacy and algorithmic biases that could exacerbate inequalities. Echoing this, a World Economic Forum piece from 2024, updated with 2025 insights, argues that AI in “Education 4.0” promotes equity by preparing students for AI-integrated workplaces, but only if implementations prioritize human oversight.

Market Growth and Institutional Shifts

The economic impetus is undeniable, with market projections painting a bullish picture. According to a Maximize Market Research report featured on OpenPR, the global AI in education sector is poised to balloon from $4.17 billion in 2023 to $53.02 billion by 2030, driven by tools automating administrative tasks and fostering interactive learning. This growth is fueled by investments in smart tutoring systems, as noted in Netguru’s blog on AI’s educational impact, which details how such technologies are streamlining everything from grading to curriculum design.

Yet, institutional adoption varies widely. A UNESCO report from early 2025, discussed during their Digital Learning Week, convened global leaders to address AI’s inclusive potential, stressing the need for policies that ensure human-centered futures. The report warns that without ethical frameworks, AI could widen digital divides, a sentiment mirrored in student perspectives from EDUCAUSE Review, where firsthand accounts with tools like ChatGPT reveal enhanced creativity but limited depth in understanding.

Educators’ Evolving Roles

Teachers are at the forefront of this shift, transitioning from lecturers to facilitators in AI-augmented environments. Insights from THE Journal’s 2025 predictions highlight experts forecasting AI’s dominance in personalized tutoring, potentially reducing teacher workloads by 30% while demanding new skills in AI literacy. Posts on X, formerly Twitter, reflect public sentiment, with users like tech influencers noting AI’s inevitability in education, comparing it to calculators’ integration and urging curricula to evolve rather than resist.

A ScienceDirect systematic review from 2024, extending into 2025 analyses, synthesizes over 100 studies showing AI’s prowess in tracking progress but cautions against replacing human interaction. This is particularly relevant in higher education, where AI aids in identifying at-risk students early, as per the U.S. Department of Education’s AI report.

Challenges in Skill Development

Deeper concerns emerge around cognitive impacts. Stone’s Conversation piece delves into experiments where AI-assisted groups showed short-term gains in creativity but struggled with original ideation without prompts, suggesting a “crutch effect.” Complementing this, a GPA Calculate Tools analysis on generative AI usage indicates that in 2025, 75% of students employ these tools, correlating with higher grades yet lower retention of core concepts.

International examples amplify these findings. China’s nationwide integration of AI into curricula, as reported on X by figures like Mario Nawfal, aims to build a tech-savvy workforce, embedding AI from primary levels to universities. However, critics argue this could prioritize rote efficiency over innovative thinking.

Future Directions and Policy Imperatives

Looking ahead, balancing AI’s benefits with safeguards is crucial. The UNESCO-convened discussions in 2025 advocate for global standards, emphasizing teacher training and equitable access. A student’s viewpoint in EDUCAUSE Review questions if systems can keep pace, proposing AI as a collaborator rather than a replacement.

Ultimately, as AI permeates education, ongoing research like that from Boise State and international bodies will guide its trajectory. By fostering thoughtful integration, stakeholders can harness AI to elevate learning without compromising the human elements that define true education.

Education

How much AI in schools? Educators wrangle with a quickly evolving tech question

How much should artificial intelligence be in classrooms?

As AI becomes more pervasive, getting included in many software apps without the possibility to remove it, educators across the region have different answers to questions about AI in schools.

Teachers have been using it to help develop lesson plans and quizzes, helping to save time in the work day. A presidential directive seeks to make teacher use of AI much more prevalent — President Donald Trump signed an executive order for more AI throughout K-12 education.

Students have been exploring it, using popular apps such as ChatGPT to help study for assignments — or even to just do the assignment. Some children are even turning to AI for companionship.

Springfield Public Schools prevents students from using most AI chatbots on school-issued devices and loops detection of student AI use in with many other tactics for focusing on teacher-student relationships. A Missouri State University educator in its College of Education said there is not a lot of AI-specific training for teachers available right now.

And a man who helped create a new private school in Springfield wants to see AI taught much more.

Rob Blevins, co-founder of Discovery School, has launched the National Institute for Artificial Intelligence in Education, a Springfield-based group that seeks to make the U.S. a global leader in K-12 AI education. The group has goals of advocating for AI educational learning standards, better training, more certification and developing bipartisan legislation for states.

The group already has initial support from U.S. Rep. Eric Burlison, Blevins said.

“There are no learning standards for AI,” Blevins said. “It’s here, people are using it and it’s not going to go anywhere. The best thing to do is get in front of it, and figure out how to handle it as responsibly as possible.”

AI: Vast applications for new technology

AI isn’t limited to one type of application.

Well-known chat apps such as ChatGPT and DeepSeek allow users to ask general questions and receive back lengthy answers.

Popular software apps from companies such as Microsoft and Adobe now offer AI functions to summarize large documents or help write rough drafts.

On our phones, Android’s Gemini and Apple’s Apple Intelligence fuel on-board, in-app AI searches within schedules, contacts and other uses.

Even social networks such as Facebook and X (formerly known as Twitter) have their own AI apps.

In general, these AI apps go far beyond a search engine — they are capable of answering conversational questions by processing a colossal amount of information available on the internet. They can also create content: They can write rough drafts of papers or create images based on a user’s needs.

What AI has in powerful data processing, it lacks in discernment.

It has been criticized for incorporating data from racists and other political actors in its results. It has also been criticized for causing damage to the environment, as the computers responsible for crunching all that data require more and more power.

It has also been used to create fake images and bizarre stories not rooted in reality, blurring the line between truth and fiction. For instance, the same president who signed an executive order to increase AI training and data centers also blamed it for an image of someone throwing something out of a White House window.

New nonprofit would like to see more AI in schools

Blevins hopes his group can emphasize the key part of using AI: remembering that we are the humans in charge of discerning and directing how results are used.

It’s something that Blevins remembers every time he uses such an app, he said.

“Being able to be the human who determines what’s appropriate, not the machine,” Blevins said. “I always try to tell it that, ‘Hey, I’m the human, my job is to figure this part out. You’re supposed to give me data.’”

His plans for his nonprofit include several goals:

• Creating a school recognition and certification program to help embed AI across curriculum, training and other student experiences.

• Hosting a debate tournament, where students score points from how they prompt, defend and navigate AI-generated arguments around real-world issues.

• Organizing a show that combines a science fair with a career expo.

SPS: Teachers’ toolbox for working with students can handle AI cheating concerns

Springfield Public Schools handles AI like any other technology used by students and teachers: carefully, with an eye on teaching students how to make effective use of such tools.

“It’s technology that has been around for a long time,” said Bruce Douglas, chief information officer for SPS. “Our approach to technology is about just preparing students for it, knowing that there is going to be new pieces for it. There is going to be change, and that’s why we focus on critical thinking skills and how we prepare students.”

Douglas said he remembers learning about AI development when he was a student at Missouri State University more than 25 years ago. Some of his professors were doing research around the neural networks and large language models that are critical components for how AI works.

Currently in SPS, ChatGPT and many other AI tools are generally blocked from student Chromebooks and other devices, although a teacher can make a case for using an AI app for a certain type of lesson. Any evaluation for teaching students about AI is looped in with the district’s normal curriculum review process.

Like other individuals and businesses that use technology, SPS employees see the software they use incorporating more AI features prominently. The district tries to review them as they surface and focuses on what helps teachers teach students.

“The use of digital resources, whether they may or may not incorporate AI, is always about the learning goals for the students,” said Thomas Maerke, a technology integration coordinator for SPS. “The learning goals for our students are going to be what drives us forward, and it’s the actions of our dedicated and hardworking teachers that make that happen.”

But AI is already in the hands of students. Social networks such as Instagram and TikTok are filled with stories of teachers who spot how students use AI to try to get around assignments.

Douglas said that the district offers no specific training about AI use among students. Instead, it emphasizes training teachers on how to be better teachers, because the toolbox teachers use to understand the work students produce can easily spot AI assistance.

That includes simple things, such as a student’s sudden jump in quality between assignments, Douglas said. It also includes more advanced tactics of ensuring academic integrity, from verifying original sources to double-checking data.

The district’s use of virtual learning and experiences among teachers at Launch Virtual Academy have helped give SPS more experience in such areas, Douglas said.

“We emphasize the relationship between the teacher and the students so much that they know what a student is producing, and we have seen that play out in a lot of different ways,” Douglas said. “It all starts with the teacher’s understanding of the students’ work, having those conversations and getting to know students.”

The district’s curriculum review process is annual. A committee of teachers and other educators evaluate a wide variety of lessons and programs, and their first priority is to check alignment with Missouri Learning Standards — the list of core curriculum for which public schools are held accountable and reviewed by the state.

Because of their need to follow state laws in order to obtain state funding, Blevins knows that public schools will be slow to take on some of the measures he supports. He sees more opportunity with private schools. He said he has been speaking with both public and private schools across the country

Next five years for AI in schools: More tinkering as an educational tool

The pervasiveness of AI, with ubiquitous features and options popping up in popular software and apps, means that teachers and students are still exploring what it can do.

Minor Baker, director of Missouri State University’s school of teaching, learning and developmental science in the College of Education, said that he sees students testing the waters. In his position, he watches educational trends across the country, but he also observes his school-aged children.

“I think right now we are definitely in the curious application mode,” Baker said. “I think teachers are trying to figure out what parts of AI can be used for their jobs.”

AI’s time-saving promises are especially attractive to teachers who are routinely asked to add daily responsibilities to their workload. Baker said that AI can assist teachers with time-intensive tasks, such as:

• Email communications with parents, such as weekly newsletters or notes about upcoming lessons. Baker said teachers could anguish over proper grammar or addressing potential questions that could arise.

• Developing lesson plans. A teacher could spend significant time locating the perfect book for a topic or a perfect experiment for a lesson. Teachers can save hours by getting AI to pore over a vast library of options.

“Teachers spend a lot of time just locating resources such as what would be a good book to go with a particular topic,” Baker said. “Now teachers can say, ‘This is what I’m teaching, this is my learning objective, I need resources that may be readily available.’”

He agrees with SPS’ approach to training teachers on spotting AI use in students, mainly because he does not see an abundance of education about that subject.

But education will transform and adapt, Baker said. He remembers Texas Instruments’ TI-82 programmable graphing calculator and how powerful it was on its release in 1993.

“I think it’s exceptionally realistic that we will begin to tinker around the edges of using AI as a learning tool, a learning partner,” Baker said. “The calculator did not necessarily change mathematics. Certainly, AI is more expansive than the TI-82. But I also think that a lot of what we do in school can be enhanced by the use of AI when it comes to developing knowledge.”

Baker said that AI isn’t inherently bad, per se. Its ability to provide answers to questions complements a child’s inherent curiosity.

He compared it to a set of encyclopedias that his grandparents offered. He would pick a letter, such as J, and see what was inside that volume. Kids’ version of that today, he said, is they can land on a random thought about something and go down a rabbit hole to see what more they can learn.

“I think that the likelihood is that over the next five years, we’re going to find that AI is integrated into lots of what we do, and we’ll be using it as a learning partner in schools without actually changing how important teachers really are,” Baker said. “I think teachers run those relationships, and what they do personally will remain the foundation of what schools are.”

As advocates such as Blevins work for more AI, and as the White House develops its AI Action Plan, Douglas said that any plan or curriculum for beefing up AI education cannot leave teachers behind.

“One of our core beliefs is that it’s really the teacher who is going to make the impact in the student’s education,” Douglas said. “That’s the first box I always look at, how we are making sure we have great teachers in our classrooms, and then how do we support them from there? … If everything is grounded in strong curriculum led by qualified educators, those two foundational pillars then guide how tools are used to support student learning.”

There is a transformation coming, Blevins said. And he hopes that a regular education about AI will help students learn how to use it for the better.

“If we don’t teach kids how to use it responsibly, then they will learn to use it irresponsibly,” Blevins said. “AI is way more powerful than anything that we’ve experienced before. In some ways, it’s exciting, the things that are going to be possible now because of the innovations that will occur.”

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms1 month ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi