Education

Schools are using AI to protect students. It also leads to false alarms — and arrests

Lesley Mathis knows what her daughter said was wrong. But she never expected the 13-year-old girl would get arrested for it.

The teenage girl made an offensive joke while chatting online with her classmates, triggering the school’s surveillance software.

Before the morning was even over, the Tennessee eighth grader was under arrest. She was interrogated, strip-searched and spent the night in a jail cell, her mother says.

Earlier in the day, her friends had teased the teen about her tanned complexion and called her “Mexican,” even though she’s not. When a friend asked what she was planning for Thursday, she wrote: “on Thursday we kill all the Mexico’s.”

Mathis said the comments were “wrong” and “stupid,” but context showed they were not a threat.

“It made me feel like, is this the America we live in?” Mathis said of her daughter’s arrest. “And it was this stupid, stupid technology that is just going through picking up random words and not looking at context.”

Surveillance systems in American schools increasingly monitor everything students write on school accounts and devices. Thousands of school districts across the country use software like Gaggle and Lightspeed Alert to track kids’ online activities, looking for signs they might hurt themselves or others. With the help of artificial intelligence, technology can dip into online conversations and immediately notify both school officials and law enforcement.

Educators say the technology has saved lives. But critics warn it can criminalize children for careless words.

“It has routinized law enforcement access and presence in students’ lives, including in their home,” said Elizabeth Laird, a director at the Center for Democracy and Technology.

In a country weary of school shootings, several states have taken a harder line on threats to schools. Among them is Tennessee, which passed a 2023 zero-tolerance law requiring any threat of mass violence against a school to be reported immediately to law enforcement.

The 13-year-old girl arrested in August 2023 had been texting with friends on a chat function tied to her school email at Fairview Middle School, which uses Gaggle to monitor students’ accounts. (The Associated Press is withholding the girl’s name to protect her privacy. The school district did not respond to a request for comment.)

Taken to jail, the teen was interrogated and strip-searched, and her parents weren’t allowed to talk to her until the next day, according to a lawsuit they filed against the school system. She didn’t know why her parents weren’t there.

“She told me afterwards, ‘I thought you hated me.’ That kind of haunts you,” said Mathis, the girl’s mother.

A court ordered eight weeks of house arrest, a psychological evaluation and 20 days at an alternative school for the girl.

Gaggle’s CEO, Jeff Patterson, said in an interview that the school system did not use Gaggle the way it is intended. The purpose is to find early warning signs and intervene before problems escalate to law enforcement, he said.

“I wish that was treated as a teachable moment, not a law enforcement moment,” said Patterson.

Students who think they are chatting privately among friends often do not realize they are under constant surveillance, said Shahar Pasch, an education lawyer in Florida.

One teenage girl she represented made a joke about school shootings on a private Snapchat story. Snapchat’s automated detection software picked up the comment, the company alerted the FBI, and the girl was arrested on school grounds within hours.

Alexa Manganiotis, 16, said she was startled by how quickly monitoring software works. West Palm Beach’s Dreyfoos School of the Arts, which she attends, last year piloted Lightspeed Alert, a surveillance program. Interviewing a teacher for her school newspaper, Alexa discovered two students once typed something threatening about that teacher on a school computer, then deleted it. Lightspeed picked it up, and “they were taken away like five minutes later,” Alexa said.

Teenagers face steeper consequences than adults for what they write online, Alexa said.

“If an adult makes a super racist joke that’s threatening on their computer, they can delete it, and they wouldn’t be arrested,” she said.

Amy Bennett, chief of staff for Lightspeed Systems, said that the software helps understaffed schools “be proactive rather than punitive” by identifying early warning signs of bullying, self-harm, violence or abuse.

The technology can also involve law enforcement in responses to mental health crises. In Florida’s Polk County Schools, a district of more than 100,000 students, the school safety program received nearly 500 Gaggle alerts over four years, officers said in public Board of Education meetings. This led to 72 involuntary hospitalization cases under the Baker Act, a state law that allows authorities to require mental health evaluations for people against their will if they pose a risk to themselves or others.

“A really high number of children who experience involuntary examination remember it as a really traumatic and damaging experience — not something that helps them with their mental health care,” said Sam Boyd, an attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center. The Polk and West Palm Beach school districts did not provide comments.

Information that could allow schools to assess the software’s effectiveness, such as the rate of false alerts, is closely held by technology companies and unavailable publicly unless schools track the data themselves.

Gaggle alerted more than 1,200 incidents to the Lawrence, Kansas, school district in a recent 10-month period. But almost two-thirds of those alerts were deemed by school officials to be non-issues — including over 200 false alarms from student homework, according to an Associated Press analysis of data received via a public records request.

Students in one photography class were called to the principal’s office over concerns Gaggle had detected nudity. The photos had been automatically deleted from the students’ Google Drives, but students who had backups of the flagged images on their own devices showed it was a false alarm. District officials said they later adjusted the software’s settings to reduce false alerts.

Natasha Torkzaban, who graduated in 2024, said she was flagged for editing a friend’s college essay because it had the words “mental health.”

“I think ideally we wouldn’t stick a new and shiny solution of AI on a deep-rooted issue of teenage mental health and the suicide rates in America, but that’s where we’re at right now,” Torkzaban said. She was among a group of student journalists and artists at Lawrence High School who filed a lawsuit against the school system last week, alleging Gaggle subjected them to unconstitutional surveillance.

School officials have said they take concerns about Gaggle seriously, but also say the technology has detected dozens of imminent threats of suicide or violence.

“Sometimes you have to look at the trade for the greater good,” said Board of Education member Anne Costello in a July 2024 board meeting.

Two years after their ordeal, Mathis said her daughter is doing better, although she’s still “terrified” of running into one of the school officers who arrested her. One bright spot, she said, was the compassion of the teachers at her daughter’s alternative school. They took time every day to let the kids share their feelings and frustrations, without judgment.

“It’s like we just want kids to be these little soldiers, and they’re not,” said Mathis. “They’re just humans.”

___

This reporting reviewed school board meetings posted on YouTube, courtesy of DistrictView, a dataset created by researchers Tyler Simko, Mirya Holman and Rebecca Johnson.

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Education

Maine Monitor: ‘Building the plane as we’re flying it’: How Maine schools are using generative AI in the classroom

By Kristian Moravec of the Maine Monitor

One platform, MagicSchool, has more than 8,500 educator accounts in Maine. As teachers and students increasingly turn to these tools, some school districts are working to codify guidelines for ethical use.

In Technology Director Mike Arsenault’s office at the Yarmouth School Department, papers and boxes sat on his desk — some of it swag from the tech company MagicSchool, one of several artificial intelligence programs the district is now using.

The AI platform, which was designed for educators, offers tools like a lesson planner, letter of recommendation producer, Individualized Education Plan drafter and even a classroom joke writer. The district pays about $10,000 a year for a MagicSchool enterprise package, and Arsenault said that his favorite element is the “Make it Relevant” tool, which prompts teachers to describe their class and what they’re studying and then generates activities that tie student interests to the subject.

“Because the question that students have asked forever is ‘why are we learning this,” Arsenault said, explaining that students should have clear examples of how lessons are useful outside of the classroom. “That’s something that AI is really good at.”

The district is one of many across Maine that is increasingly using AI in its classrooms. Some, like Yarmouth, have established formal AI guidelines. Others have not. MagicSchool told The Monitor that it has around 8,500 educator accounts active in Maine. This would equate to more than half of the state’s public school teachers, though anyone can sign up for a free educator account.

The state Department of Education does not yet have data on how many teachers or school districts are using AI, but said that based on the level of interest schools have for AI professional development, its use is widespread. The department is conducting a study to better understand how schools are integrating the new technology and hopes to release data next spring, according to a spokesperson.

The use of generative AI — a type of artificial intelligence that generates new text, images or other content, such as the technology used in ChatGPT — is prompting a growing debate in education. Critics see it as a tool that decreases critical thinking and helps students cheat, while advocates see it as a fixture that students must learn how to use ethically.

A majority of teachers across the country are growing familiar with AI for either personal or school use, and suspect that their students are using it widely as well, according to a 2024 study by the Center for Democracy and Technology.

As AI changes come at breakneck speed, leaders are pushing for its controlled use in schools. Roughly half of states have some form of AI guidance in place, according to the Sutherland Institute.

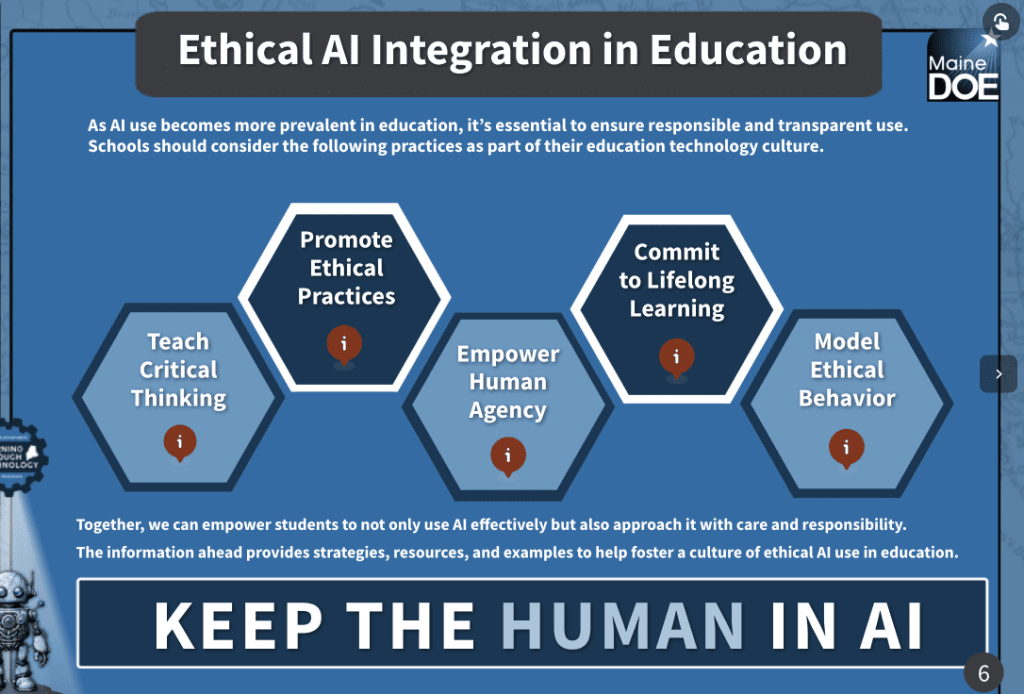

Maine introduced an interactive AI guidance toolkit earlier this year, which walks educators through ways they can integrate AI in the classroom from pre-Kindergarten to 12th grade and the questions to consider when doing so. Students in pre-Kindergarten through second grade could “use AI to generate art and have students collboarate [sic] to create a shared image,” according to the guidance, or high school students could “explore cybersecurity principles through ethical hacking simulations.”

The guidance encourages teachers to “keep the human in AI” by stopping to ask if its use is appropriate for the task, monitoring for accuracy and noting how AI was used.

The governor’s office launched a state AI Task Force last year to prepare Maine for the “opportunities and risks likely to result from advances in AI” in private industries, education and government. The task force’s education subgroup has met three times this year, and plans to release a report on AI use in Maine this fall.

For Yarmouth Superintendent Andrew Dolloff, it is important to help students tackle the increasingly popular technology in a safe environment. The district adopted its first set of AI guidelines last year, which emphasize that staff should be transparent and cite any use of generative AI, ensure student data privacy is protected, be cautious of bias and misinformation and understand the technology “as an evolving tool, not an infallible source.”

“AI is here to stay. It’s part of our lives. We’re all using it as adults on a daily basis. Sometimes without even knowing it or realizing that it’s AI,” Dolloff said. “So we changed our stance pretty quickly to understand that rather than trying to ban AI, we needed to find ways to effectively use it, and allow students to use it appropriately to expand their learning.”

Maine School Administrative District 75 — which serves Harpswell, Topsham, Bowdoin and Bowdoinham — adopted an AI policy earlier this year, though some school board members were hesitant to approve the policy over concerns that generative AI can help students cheat and produce misinformation, The Harpswell Anchor reported.

Some school districts, such as Regional School Unit 22, which serves Hampden, Newburgh, Winterport and Frankfort, have launched internal committees to guide AI use, while others, such as MSAD 15 in Gray and New Gloucester, are pursuing policies in the wake of controversy.

Earlier this year, a student at MSAD 15 alleged that a teacher graded a paper using AI, WGME reported. Superintendent Chanda Turner told The Maine Monitor that teachers are piloting programs that use AI to give feedback on papers, but are not using it to issue grades. The school board will be working on an AI policy for the district this school year, she said.

Nicole Davis, an AI and emerging technology specialist with the DOE who helped write the state guidelines, estimates that over 40 school districts in Maine have requested professional development for AI, and expects that interest will grow. She noted that guiding AI use can be a challenge, as the technology changes so quickly.

“We’re building the plane as we’re flying it,” Davis said.

‘I was stunned’

Julie York, a computer science teacher at South Portland High School, has long incorporated new technology into her teaching, and has found generative AI tools like ChatGPT and Google Gemini to be “incredibly useful.” She has used it to create voiceovers for presentations when she was tired, to help make rubrics and lesson plans and to build a chatbot that can answer questions during class, which she says helps her balance the amount of time she spends with each student.

“I don’t think there’s any educator who wakes up in the morning, and is like, ‘oh my god, I hope I can make a rubric today.’ I just don’t think you’re going to find any,” she said. “And there’s no teacher who isn’t tired.”

She vets all the AI resources she uses before integrating them into her work, and has discussions with her students about when using AI is appropriate. Student use is guided by the traffic light model: if an assignment is green, students can use AI under the guidance of a teacher, if it’s yellow that means limited use with teacher permission, and red means no AI. She makes these determinations depending on the type of assessment. If she wants them to be able to read code and understand what it does, for instance, then AI cannot be used. But if a student is coding a computer program, she said, then AI can be a useful tool.

AI can also help teachers accommodate diverse needs, York said, explaining that students who have trouble speaking in front of a class could use text-to-voice software to produce voiced-over videos. The district’s students speak several different languages, and she used AI to help her create an app that translates her speech into multiple languages while she’s teaching. It took her about an hour to make.

“I just sat there stunned at my computer. Just stunned,” York recalled.

Maine Education Association President Jesse Hargrove said that teachers are exploring the evolving AI landscape alongside their students, noting that AI can help create steps for science projects, or detect whether students cheated.

“I think it’s being used as a partner in the learning, but not a replacement for the thinking,” he said.

MEA’s approach to AI is guided by the National Education Association’s policy, which emphasizes putting educators at the center of education. However, Hargrove said that MEA does not have a stance on whether or not districts should adopt AI.

“We believe that AI should be enhancing the educational experience rather than replacing educators,” he said.

‘Click. Boom. Done.’

Maine’s AI guidance emphasizes that teachers should have clear expectations for AI use in the classroom. It recommends being specific about grade levels, lesson times, content and general student needs when prompting services like ChatGPT to generate lesson plans.

The state told The Monitor it does not recommend any AI tools in particular. Instead, the DOE said it encourages schools to research tools and consider data security, privacy and use.

But its guidance toolkit references a handful of specific programs. MagicSchool and Diffit are listed as tools that can help with accessibility in the classroom. Almanack, MagicSchool and Canva are noted as tools that can help boost student engagement.

The types of AI tools that educators use vary depending on their needs, Davis said, but there seem to be five tools that can assess papers, create study materials and help build curriculums that schools are turning to the most: Diffit, Brisk, Canva, MagicSchool and School AI.

“That batch of essays that’s looming? Brisk will help you grade them before the bell rings,” Brisk’s website reads. “Need a lesson plan for tomorrow? Click. Boom. Done.”

Use of these platforms is regulated by legal parameters for student data safety, such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and Maine’s Student Information Privacy Act. Technology companies must sign a data privacy agreement for the states in which they plan to operate. Maine’s data privacy agreement with MagicSchool, for instance, covers nine other states and sets guardrails for student data collection such as leaving ownership and control of data to “local education agencies.”

Some education-based AI companies also have their own parameters in place. MagicSchool, which was founded by former educator Adeel Khan, requires teachers to sign a best practices agreement, reminds them not to enter personal student information into AI prompts like an Individual Education Plan generator, and claims it erases any student information that gets entered into its system.

“We’re always iterating and trying to make things safer as we go,” Khan said, citing MagicSchool’s favorable rating for privacy on Common Sense Media, an organization that rates technology and digital media for children.

The federal government has also pushed for the use of AI in schools. In the spring, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to promote AI in education, and the federal Department of Education has since published a letter encouraging the use of grant funding to “support improved outcomes for learners through responsible integration of artificial intelligence.”

In late August, First Lady Melania Trump launched the Presidential AI Challenge: asking students to “create AI-based innovative solutions to community challenges.”

The White House is also running a pledge campaign, “Investing in AI Education,” asking technology companies to commit resources like funding, education materials, technology, professional development programs and access to technical expertise to K-12 students, teachers and families for the next four years. More than 100 entities have signed on, including MagicSchool.

In Maine, the DOE is working on broader AI professional development for teachers, with plans to launch a pilot course based on the state’s AI guidance toolkit, potentially as soon as this fall.

As Yarmouth starts the new school year, Arsenault said that AI should be integrated with the goal of preparing students for a future that will be filled with AI.

“We can do what many schools do and ignore it, or we can address it,” Arsenault said. “And if we address it with our students, we have the ability to frame the discussion on how it’s used, and have discussions with our students about how we want to see it used in our classrooms.”

Education

AI in the classroom – the upending of traditional education

On a recent episode of the New York Times’ Hard Fork podcast, I was startled to hear about an “AI-first” school that has used AI to reduce academic teaching time to a mere two hours per day and has redeployed teachers to be mentors and guides, rather than deliverers of content, policing, and grading.

What happens after the two-hour academic class? Lots of fun, apparently – collaboration games, motivation exercises, and life skills activities. The school boasted that students are scoring in the 99th percentile nationally for its core curriculum. Oh, and no homework. Ever.

We’ll get back to the veracity of these claims in a moment. Most of the discussion about AI and students has been around the use of GenAI to circumvent the hard work of doing homework and essays and reading, by passing that job over to a chatbot, which generally does fine work on their behalf – at least if you are a student looking to shirk responsibilities and don’t object to a bit of plagiarism.

Schools and teachers, unsurprisingly, were rather irritated by this and instituted various fightback campaigns ranging from threats to AI bans to punishments to technology-based chatbot plagiarism detectors (the latter now generally agreed to be hopelessly inadequate).

Some educators are now realising that this is all a waste of time. Students are going to use GenAI wherever they can: at school, at home, in the bathroom. One current study has 63% of US high-school students using AI in ways that they know contradict school policy. There is no way to stop it, and it is becoming apparent that perhaps it should be encouraged within carefully designed guardrails.

And so a new crop of education initiatives is blooming where the AI designs the course plan, does the teaching, the monitoring, the personalised assistance, the remedial support (where appropriate), as well as the evaluations and grading. This leaves the teacher free to concentrate on softer skills like coaching and mentorship, making the school a more joyous and expansive experience for both students and teachers.

How is it going? The school I mentioned earlier is Alpha Schools, which now operates three campuses in the US. It is one of the better-known AI-first ventures. Its model is mixed-age microschools using adaptive platforms so students “learn 2x in 2 hours,” then spend afternoons on projects, mentorship, and life skills.

Deliberately disruptive

The idea is deliberately disruptive – take the tedium out of repetitive content acquisition and give time back for exploration. Independent observers and critics are understandably sceptical of headline ratios such as “2 times faster” learning; some commentators have flagged that such claims need careful scrutiny and peer-reviewed evidence.

In the podcast co-founder MacKenzie Price enthusiastically proclaims:

“We practise what’s called the Pomodoro Technique. So, kids are basically doing like 25 minutes of focused attention in the core academics of maths, reading, language, and science. They get breaks in between, and then by lunchtime, academics are done for the day and it’s time to do other things.

“So in the afternoon is where it gets really exciting because when kids don’t have to sit at a classroom desk all day long, just grinding through academics, we instead use that time for project-based, collaborative life-skills projects. These are workshops that are led by our teachers – we call them guides – and they’re learning skills like entrepreneurship and financial literacy and leadership and teamwork and communication and socialisation skills.”

There has been some grumbling about her claims. They are self-reported numbers, and a couple of parents have been critical. Also, the school is not cheap, so the results would certainly show some selection bias. On the other hand, they do not reject children with poor academic track records, which is more than can be said for other private schools.

Pushed the conversation

Still, places like Alpha have pushed the conversation from “can we use AI in classrooms?” to “how radically should we reorganise the school day around it?” – and that question is exactly the kind of policy and practice debate we need.

There are other schools too, like the private David Game College in London, currently piloting an AI-first teaching curriculum for 16-year-olds, which looks very similar to Alpha Schools, with similar sterling results. But there are only 16 students in the pilot, so the jury remains out.

What about the public-school system? Is AI just for the rich? Turns out, no. There is an impressive case study in Putnam County Public Schools in Tennessee. Facing a severe shortage of computer science teachers, the school district partnered with an AI platform called Kira Learning.

What happened next was a true testament to the power of a good hybrid model: 1,200 students enrolled, and every single one of them passed the course – which would be remarkable in any subject, let alone computer science. This wasn’t “AI-first” in the Alpha School sense. It was “AI-for-all,” a tool that levelled the playing field and brought a vital skill to students who might otherwise have missed out. The teachers weren’t replaced; they became “facilitators,” freeing them from grading and lesson planning to focus on student engagement.

It is not only students that benefit. Consider AcademIQ in India, an AI-powered educational application designed to revolutionise the learning experience for teachers, students, and parents, particularly in multilingual and low-resource classrooms. Launched in 2023, the platform is India’s first to be built around the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020.

Simplicity

The platform’s primary appeal lies in its simplicity. It offers over 150 AI tools, most notably an “instant NEP-aligned lesson plan generator” that requires no prompts or technical expertise. Teachers simply select a class, subject, and topic to receive a complete lesson plan in seconds. This is a direct response to a major pain point for educators; testimonials indicate the platform can reduce weekly lesson-planning time by several hours, freeing up teachers to focus on student engagement.

What then of pedagogy – the art and science of teaching? Universities, which have a long heritage in teacher training, are notoriously slow to change curricula. If it is true that everything except the interpersonal roles of mentorship, coaching, and guidance will be outsourced to much more efficient AI teachers, what then should be the requirements of a teaching degree or certificate? It is not clear that anyone has wrestled with this question sufficiently, particularly given AI’s dizzying rate of improvement.

For those teachers terrified of these coming changes, but resigned to the imminent primacy of AI tutors, there is this comfort – no more lesson plans, no more grading, no more one-size-fits-all. Just the nobler task of shaping the critical human traits of motivation, confidence, enthusiasm, collaboration, and childhood curiosity.

That sounds much more satisfying than the old way.

[Image: Photo by Element5 Digital on Unsplash]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend

Education

Rochester CUSD launches new AI program for educator use | Education

We recognize you are attempting to access this website from a country belonging to the European Economic Area (EEA) including the EU which

enforces the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and therefore access cannot be granted at this time.

For any issues, contact news@wandtv.com or call 217-424-2500.

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms4 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi