AI Insights

AI Wrote a Better Cover Letter Than Me; I Don’t Care | Features

Image generated by Archinect using AI

As AI adoption in the job application process surges, I pit myself against four leading AI tools to craft a cover letter for a fictional architecture job. After a ‘spot the human’ challenge among Archinect’s editors and our readers, I share my thoughts on both the experience of using AI to prepare a cover letter and where I will and will not use it in the future.

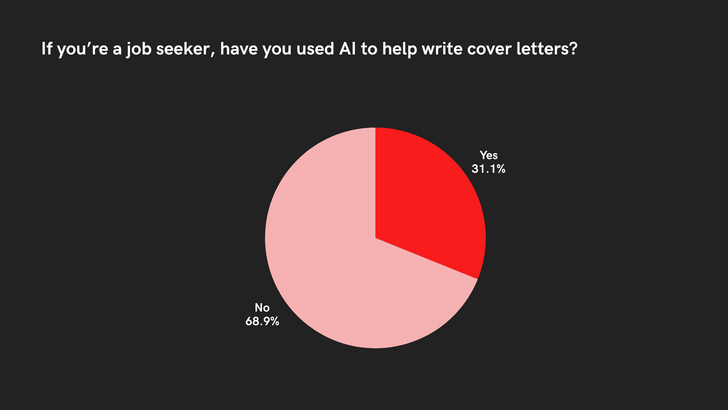

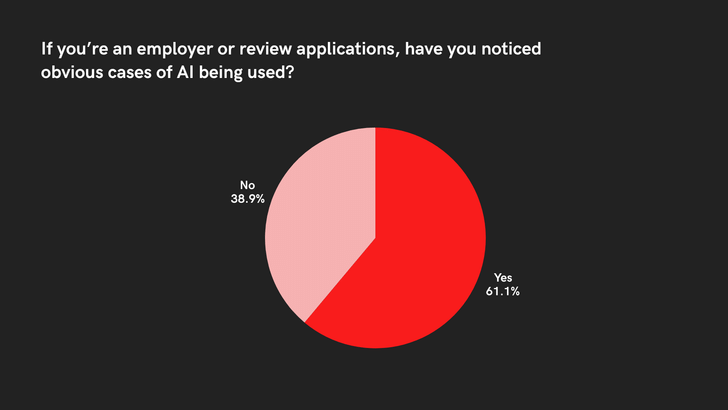

AI Adoption in Cover Letters

The next time you sit down to review job applications for an open position at your architecture firm, the words you read may not be entirely human. In January 2024, a survey by graphic design platform Canva found that 45% of job seekers have used artificial intelligence to create, update, or edit their résumé, while a survey of Archinect readers conducted last month found that one-third of job applicants have used AI to help write their cover letters. In that same survey, over 60% of employers told us that they had seen obvious cases of AI being used in job applications.

“For better or for worse, AI is now part of the job application process,” career expert Ethan David Lee told Forbes late last year. “Job seekers must learn how to use AI as an asset and not as a shortcut. Hiring managers don’t mind AI in applications, but when it’s used carelessly, the result feels impersonal and fails to stand out.”

Since 2023, when I undertook the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series, I have continued to engage with generative AI platforms, from text generators such as ChatGPT and Claude to image and video generators such as MidJourney and Sora. In the intervening two years, the quality of material generated by such systems has increased dramatically, as has our understanding of how to use AIs effectively to achieve a desired output. The growing adoption of these systems in job applications raises a question: How do AI systems measure against humans when creating a cover letter?

Creating AI Cover Letters

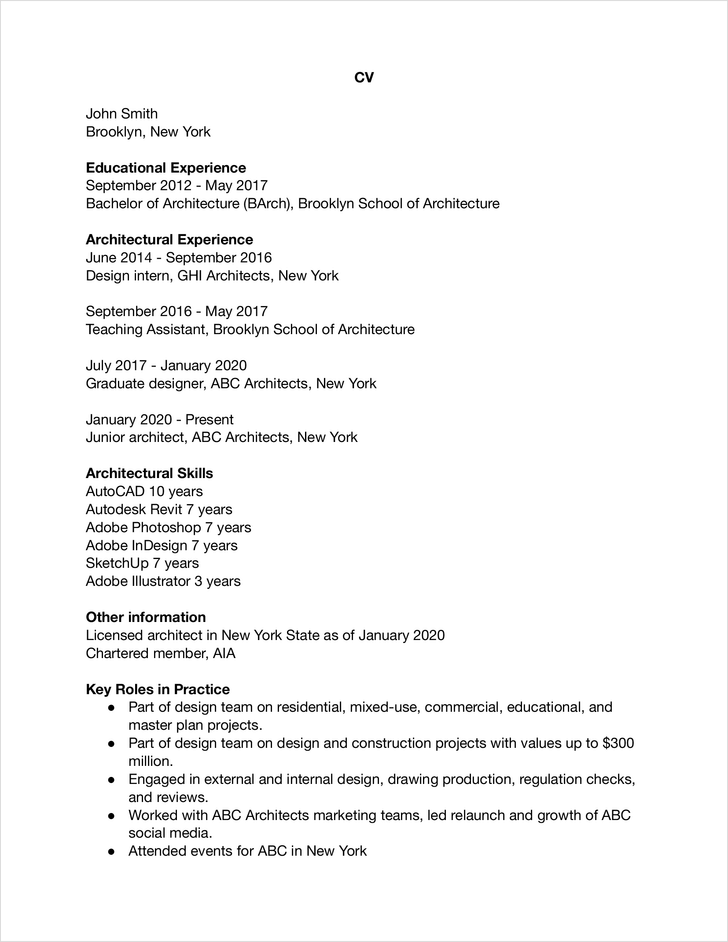

To find out, I conducted an experiment involving myself, Archinect’s editorial team, and you, our readers. Inspired by typical listings on Archinect Jobs, I created a sandbox job ad for a Junior Architect position at XYZ Architects, a fictitious New York firm. I then created an avatar applicant, John Smith, structuring John’s CV to reflect the typical pathway, experiences, and skills of a recently licensed architect. With my fictitious job ad and fictitious applicant created, I turned to AI.

Using four AI systems, I generated four cover letters that John Smith could use in his job application to XYZ. For the three conversational AIs I used, namely ChatGPT, Claude Sonnet, and Google Gemini, the process was identical. “My name is John Smith, and I am applying for a new architecture job,” I told the bots. “I want you to write my cover letter. What do you need from me to do this?”

The responses, too, were almost identical, with each AI bot asking me to provide information on the position and company, my professional background, my skills and strengths, my alignment for the role, and my motivation for applying. In my reply message for each, I pasted the full text of the test job ad, followed by my (John’s) CV. To the question of my alignment and motivation for the role, I was rather blunt: “Write whatever you think gives me the best chance of getting the job.”

With 15 minutes of minimal effort, I had generated three cover letters from three AI systems, which, on first glance, showed little evidence of being artificially generated. The fourth cover letter, created by Grammarly’s AI cover letter generator, followed similar steps, prompting me to upload my CV, enter the job title I was applying for, and paste the responsibilities and requirements listed in the job description. Seconds later, the cover letter appeared.

The ease with which four AI bots had spat out cover letters in seconds only made the hour of manual cover letter composition feel more lethargic and, perhaps, more unnecessary.

To accompany the four AI-generated cover letters, I drafted a fifth myself, drawing on the structure of previous successful cover letters I had used in my own career, and adapting the information to match the CV of my avatar, John Smith. Despite having the template of previous cover letters as a starting point, the process was nonetheless time-consuming, as any job applicant can attest. The ease with which four AI bots had spat out cover letters in seconds only made the hour of manual cover letter composition feel more lethargic and, perhaps, more unnecessary.

A Clear Favorite

Nonetheless, after a morning’s work, five cover letters lay before me; one written by me with no AI involvement, and four written by AI with no editing or intervention by me, apart from Grammarly’s cover letter requiring me to replace [FIRM NAME] with XYZ Architects.

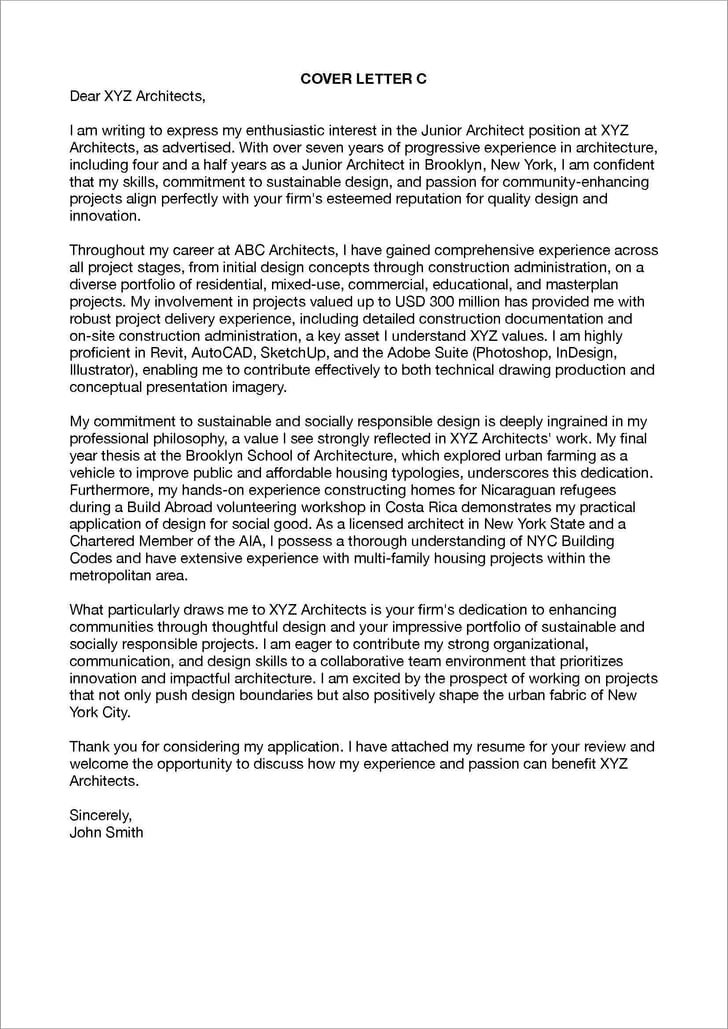

Reviewing the five letters, I wondered whether this experiment had even been worthwhile. To me, the four AI cover letters seemed alien and lifeless, each with its own quirks. Cover Letter A, written by Grammarly, made an early irrelevant reference to the job being posted on “Archinect Job,” while Cover Letter B, written by ChatGPT 4.5, missed what I consider a golden rule of cover letters: Explain in the first paragraph why you are attracted to the specific firm you are writing to. Cover Letter C, written by Google Gemini 2.5 Flash, was distractingly heavy on adjectives, while Cover Letter E, written by Claude Sonnet 4, presented as unnecessarily long and cumbersome.

By ceding control of the cover letter composition to AI, I couldn’t help feeling that I had also ceded control of my story.

Cover Letter D, which I authored, stood out to me. Of course it did; I wrote it. This was my own articulation of my professional journey and value; the result of asking myself: ‘What’s so special about me?’ The information contained in the letter, both the order of information and connections formed between paragraphs, seemed to me to fall into place like pieces of a jigsaw, ultimately painting a picture of me that I was proud of; that I would want a prospective employer to read and ask me about.

The four AI-generated cover letters, though accurate representations of my journey, lacked that same energy, regardless of how much I read and attempted to identify with them. By ceding control of the cover letter composition to AI, I couldn’t help feeling that I had also ceded control of my story. To me, Cover Letter D was evidently the most human and the most effective. Were I to apply to the job, it would have been with Cover Letter D: my cover letter.

Archinect Plays ‘Spot the Human’

Given the inevitable bias in my judgment on the five cover letters, I turned to more neutral actors to understand how my cover letter fared alongside its AI-generated counterparts. To begin, I recruited my colleagues at Archinect, namely founder and director Paul Petrunia, and managing editor Alexander Walter. Their challenge was straightforward: Read each cover letter, and identify which letter I had written. Paul and Alexander knew that four of the letters were AI-generated, but had no information on which AI tools were used, or how I used them. One week later, we reconvened to unveil and discuss the results.

Given my own conviction on how uniquely human Cover Letter D was compared to the four AI-generated letters, I entered the conversation expecting Paul and Alexander to express similar sentiments. I expected a conversation to largely revolve around how Cover Letter D stood out for its expressiveness and natural flow, while the other letters took criticism for their exaggerated language, illogical quirks, and general lack of character. I therefore began by asking Alexander and Paul which cover letter they believed I had written, expecting a chorus of “Cover Letter D” in return.

“It wasn’t very easy [to figure out] after reading through them all, but I believe that you wrote Cover Letter C,” Alexander began.

“Specifically because it is you, and I know you’re a good writer who is careful with your writing, I’m going to say B,” Paul added. “If I didn’t know who was writing it, I would have said D, because D has some hilariously bad mistakes which I am surprised, at this point in the evolution of AI, that a large language model would make.”

As Paul spoke, I frantically scanned Cover Letter D. As if reading with a new set of eyes, errors appeared seemingly from nowhere. Instead of addressing the letter to XYZ Architects, I wrote ‘WXY Architects,’ ironically, a real firm practicing in New York City. In the next line, instead of naming ABC Architects as my current employer, I had written XYZ Architects. Mixing up the names of people and companies can be a common error in emails and letters, but doing so twice in the first two lines of a letter designed to express your interest in a job, fictitious or not, only compounded the embarrassment. As the human-generated Cover Letter D took round after round of criticism on its mistakes and oddities, the four AI-generated letters sat largely unaddressed; no doubt smugly basking in their clinical superiority. I was right that at least one of my colleagues would spot the human cover letter, but I was right for the wrong reasons.

I don’t think employers are going to want to look at cover letters that are all formatted exactly the same way. — Paul Petrunia

With the suspense over, our conversation turned to the emerging use of AI in cover letters across the industry. While my experiment demonstrated that AI could write a cover letter of greater clarity and accuracy, Alexander, Paul, and I nonetheless wondered if the concise nature of the four AI cover letters also removed the personal touch and creativity that a human-written letter, such as Cover Letter D, can provide.

“Has AI gotten to the point where it is determined: ‘This is the ultimate way to write a cover letter, and we’re going to do it this way for everybody that asks an AI to help them write a cover letter’?” Paul wondered. “The result ends up being pretty boring. I don’t think employers are going to want to look at cover letters that are all formatted exactly the same way. It makes me feel like employers will probably look out for more non-traditional cover letters that express creativity, even if they may not fit the model of a perfect cover letter.”

A Challenge to Readers

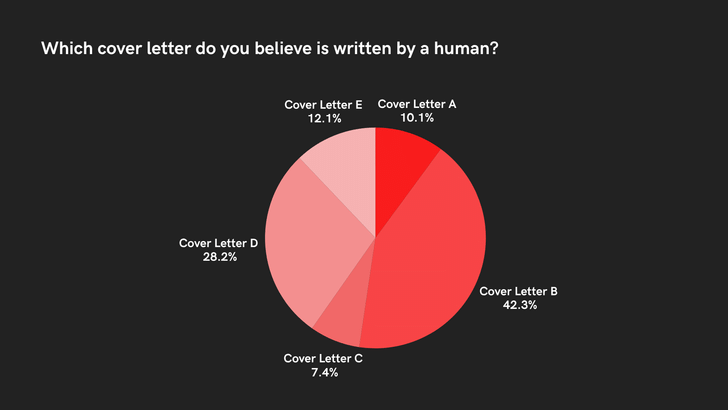

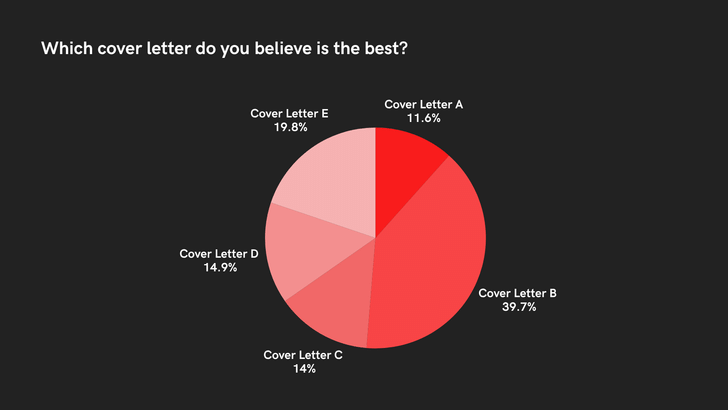

To further explore our hypotheses, we opened our experiment up to Archinect readers. Late last month, we presented all five letters to our community, and challenged them to identify which letter they believed was human-authored, as well as tell us which they believed was the ‘best’ cover letter. While the full results of our challenge will be published in the coming days, we can reveal that, like in Archinect’s own team, our readers were divided. Only 28% correctly identified Cover Letter D as being human-authored, with the largest share (42%) instead opting for Cover Letter B, which in reality was authored by ChatGPT.

“It feels slightly more to the point and less generic than the others,” one reader told us on why they chose Cover Letter B. “The narrative also is stronger in my opinion, and it’s also the shortest letter of all.”

“The others have excessive superlatives that give the letters a generic quality,” another reader told us, who correctly chose Cover Letter D as human-authored. “D also has superlatives but expands on them enough to suggest this is a person speaking because it gets into a bit more detail.”

Our readers were even more divided on the question of which cover letter was ‘best’ in their eyes. While 40% again chose ChatGPT’s Cover Letter B as their preference, almost 20% chose the Claude Sonnet-authored Cover Letter E.

Just under 15% believed Cover Letter D, written by me, was best. No offence taken, readers.

Micro-Experiment 1: AI Detectors

Before bringing my journey through AI cover letters to an end, I conducted two further micro-experiments inspired by the feedback gained from my Archinect colleagues and readers. The first micro-experiment was inspired by the results of our reader challenge, where almost three-quarters of readers failed to correctly identify the human-generated cover letter among the AI impostors. Perhaps tools specifically designed for this task would perform better?

To find out, I turned to two popular AI detection software tools, each of which allows users to upload or paste text in return for feedback on what percentage of the text is likely generated by AI. Specifically, I chose ZeroGPT and Grammarly AI; two popular, free, and accessible detection tools.

Given that Cover Letter D had zero interference from AI, and all other cover letters had zero interference from humans, an accurate result from the detection software would read 100% for Cover Letters A, B, C, and E, and 0% for Cover Letter D. ZeroGPT was impressive in its results, with all four AI-generated cover letters scoring 97% to 99%. Less impressive, however, was its estimate that 35% of Cover Letter D, authored by me, was AI-generated.

Humans may struggle to differentiate between an AI and human text, but evidently, so too does AI.

Where ZeroGPT was lavish in its AI accusations, Grammarly was understated. Although Cover Letter A was itself written by Grammarly AI, the same platform’s AI detector gave it a score of 50%. Cover Letters B, C, and E scored 25%, 44%, and 40% respectively, while the human-authored Cover Letter D correctly scored 0%.

Both tools, then, were directionally correct in giving the human-generated Cover Letter D a significantly lower score than its AI counterparts. When the cover letters are viewed in isolation, however, the unreliability of such tools is exposed. An employer who only reviews Cover Letter D through ZeroGPT would be led to believe, falsely, that over one-third of the letter was AI-generated. Meanwhile, a separate employer reviewing the ChatGPT-generated Cover Letter B, using Grammarly’s AI detection tool, would falsely believe that 75% of the letter was human-authored. Humans may struggle to differentiate between an AI and human text, but evidently, so too does AI.

Micro-Experiment 2: The Hybrid

For my second micro-experiment, I wondered if a hybrid could be sought between the accuracy and clarity of the four AI-generated cover letters in our challenge and the connection I felt with my own Cover Letter D. Turning to ChatGPT, which the largest share of readers believed to have produced the ‘best’ and ‘most human’ cover letter of the five, I once again inputted John’s CV and the job advert from XYZ Architects. This time, however, I also added Cover Letter D, asking ChatGPT to “correct any errors and make recommendations to improve it.”

As further proof that I, and only I, saw promise in Cover Letter D, ChatGPT responded by critiquing the “wordiness and repetition” of my writing, alongside “focus drift” and a flow and structure which “reads awkwardly.” While ChatGPT claimed to produce a “tightened, corrected, and more tailored” version in response, the resulting cover letter it generated bore little resemblance to its human ancestor. In my eyes, I had once again arrived at a detached, alien body of text which I had little connection to.

“I don’t like this,” I replied, my pride and faith in my writing lying in tatters before me. “Rewrite my cover letter, but only with errors corrected.” ChatGPT complied. Seconds later, at the end of a long, winding road, I had before me a cover letter, written by me, in my voice, addressed at last to the correct recipient.

My Final Decision

Looking back at my journey through this experiment, the data appears conclusive: AI systems can write a better, more human-sounding cover letter about me than I can about myself. After all, 72% of readers believed that one of the four AI-generated cover letters in our set was human, while 85% believed that one of those four cover letters was better than mine. Even if cover letters present a relatively minor hurdle to clear in the job application process versus more substantive components such as portfolios and work samples, this experiment has suggested that the heavy use of AI in cover letters makes clearing that hurdle more likely, in a fraction of the time.

And yet, knowing this, I choose to ignore this suggestion and stick with Cover Letter D; my cover letter. To some, this decision may seem like stubbornness or the ill effects of pride. I take a different view. A cover letter presents me, and many of us, a rare opportunity to tell the story of our career to an audience interested in reading about it. I see value, satisfaction even, in the process of reflecting on, articulating, and sharing that story. As of 2025, the impressive spectacle of AI tools generating their version of this story within seconds is still not a substitute for the experience of telling my own story in my own words.

A cover letter presents me, and many of us, a rare opportunity to tell the story of our career to an audience interested in reading about it.

My decision to stick with my own human-authored cover letter is not only sentimental but practical. Any candidate for an architecture job interview will be aware of the stresses and demands that interview preparation places on the interviewee. In addition to remaining calm and respectful, one must arrive prepared to display intricate knowledge not only of the work in their own portfolio and learnings from their prior experience but also an awareness of the culture and work of the firm they are applying to.

To arrive at an interview without complete faith or understanding of those narratives as expressed in my cover letter is to induce extra unnecessary, avoidable anxiety. For some, this could even be accompanied by a latent guilt in the knowledge that this letter, which the person(s) sitting opposite me believe I wrote, isn’t truly mine.

This doesn’t mean I won’t use AI in the process. As my second micro-experiment demonstrated, ChatGPT was capable of reviewing my cover letter and spotting glaring errors at the beginning, such as addressing the letter to the wrong firm. In a real-life setting, this error alone would have proved fatal for many job applications.

The best I can do is introduce myself to them in my own words.

Perhaps if this were a real-life setting, and I truly were applying for a job at XYZ Architects, I would have been more studious and attentive. However, if I were using this letter in a real-life setting to apply to several firms all with different names, perhaps the risk of mixing names up would actually have increased. Regardless, for important texts such as cover letters in the future, I will indeed use an AI tool as an assistant; partly as a stimulant for additional views, inputs, and suggestions, but more importantly, as a failsafe against human error.

Meanwhile, the data from this experiment gave me one final insight. While the overwhelming majority of readers did not believe my cover letter was ‘the best,’ they didn’t believe any cover letter was best. None of the five cover letters managed to attract the praise of a majority of readers, while all five letters caught the attention of at least some readers. As Steve Jobs observed, people don’t really know what they want. AI doesn’t know what they want either. The best I can do is introduce myself to them in my own words.

AI Insights

AI Can Generate Code. Is That a Threat to Computer Science Education?

Some of Julie York’s high school computer science students are worried about what generative artificial intelligence will mean for future careers in the tech industry. If generative AI can code, then what is left for them to do? Will those jobs they are working toward still be available by the time they graduate? Is it still worth it to learn to code?

They are “worried about not being necessary anymore,” said York, who teaches at South Portland High School in South Portland, Maine. “The biggest fear is, if the computer can do this, then what can I do?”

The anxieties are fueled by the current landscape of the industry: Many technology companies are laying off employees, with some linking the layoffs to the rise of AI. CEOs are embracing AI tools, making public statements that people don’t need to learn to code anymore and that AI tools can replace lower or mid-level software engineers.

However, many computer science education experts disagree with the idea that AI will make learning to code obsolete.

Technology CEOs “have an economic interest in making that argument,” said Philip Colligan, the chief executive officer of the Raspberry Pi Foundation, a U.K.-based global nonprofit focused on computer science education. “But I do think that argument is not only wrong, but it’s also dangerous.”

While computer science education experts acknowledged the uncertainty of the job market right now, they argued it’s still valuable to learn to code along with foundational computer science principles, because those are the skills that will help them better navigate an AI-powered world.

Why teaching and learning coding is still important, even if AI can spit out code

The Raspberry Pi Foundation published a position paper in June outlining five arguments why kids still need to learn to code in the age of AI. In an interview with Education Week, Colligan described them briefly:

- We need skilled human programmers who can guide, control, and critically evaluate AI outputs.

- Learning to code is an essential part of learning to program. “It is through the hard work of learning to code that [students] develop computational thinking skills,” Colligan said.

- Learning to code will open up more opportunities in the age of AI. It’s likely that as AI seeps into other industries, it will lead to more demand for computer science and coding skills, Colligan said.

- Coding is a literacy that helps young people have agency in a digital world. “Lots of the decisions that affect our lives are already being taken by AI systems,” Colligan said, and with computer science literacy, people have “the ability to challenge those automated decisions.”

- The kids who learn to code will shape the future. They’ll get to decide what technologies to build and how to build them, Colligan said.

Hadi Partovi, the CEO and founder of Code.org, agreed that the value of computer science isn’t just economic. It’s also about “equipping students with the foundation to navigate an increasingly digital world,” he wrote in a LinkedIn blog post. These skills, he said, matter even for students who don’t pursue tech careers.

“Computer science teaches problem-solving, data literacy, ethical decision-making and how to design complex systems,” Partovi wrote. “It empowers students not just to use technology but to understand and shape it.”

With her worried students, York said it’s her job as a teacher to reassure them that their foundational skills are still necessary, that AI can’t do anything on its own, that they still need to guide the tools.

“By teaching those foundational things, you’re able to use the tools better,” York said.

Computer science education should evolve with emerging technologies

If foundational computer science skills are even more valuable in a world increasingly powered by AI, then does the way teachers teach them need to change? Yes, according to experts.

“There is a new paradigm of computing in the world, which is this probabilistic, data-driven model, and that needs to be integrated into computer science classes,” said Colligan.

The Computer Science Teachers Association this year released its AI learning priorities: All students should understand how AI technologies work and where they might be used, the association asserted; students should be able to use and critically evaluate AI systems, including their societal impacts and ethical considerations; students should be able to create and not just consume AI technologies responsibly; and students should be innovative and persistent in solving problems with AI.

Some computer science teachers are already teaching about and modeling AI use with their students. York, for instance, allows her students to use large language models for brainstorming, to troubleshoot bugs in their code, or to help them get unstuck in a problem.

“It replaced the coding ducks,” York said. “It’s a method in computer science classes where you put a rubber duck in front of the student, and they talk through their problem to the duck. The intention is that, when you talk to a duck and you explain your problem, you kind of figure out what you want to say and what you want to do.”

The rise of generative AI in K-12 could also mean that educators need to rethink their assignments and assessments, said Allen Antoine, the director of computer science education strategy for the Texas Advanced Computing Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

“You need to do small tweaks of your lesson design,” Antoine said. “You can’t just roll out the same lesson you’ve been doing in CS for the last 20 years. Keep the same learning objective. Understand that the students need to learn this thing when they walk out. But let’s add some AI to have that discussion, to get them hooked into the assignment but also to help them think about how that assignment has changed now that they have access to these 21st century tools.”

But computer science education and AI literacy shouldn’t just be confined to computer science classes, experts said.

“All young people need to be introduced to what AI systems are, how they’re built, their potential, limitations and so on,” Colligan said. “The advent of AI technologies is opening up many more opportunities across the economy for kids who understand computers and computer science to be able to change the world for the better.”

What educators need in order to prepare students for what’s next

The challenge in making AI literacy and computer science cross-curricular is not new in education: Districts need more funding to provide teachers with the resources they need to teach AI literacy and other computer science skills, and educators need dedicated time to attend professional development opportunities, experts said.

“There are a lot of smart people across the nation who are developing different projects, different teacher professional development ideas,” Antoine said. “But there has to be some kind of a commitment from the top down to say that it’s important.”

The Trump administration has made AI in education a focus area: President Donald Trump, in April, signed an executive order that called for infusing AI throughout K-12 education. The U.S. Department of Education, in July, added advancing the use of AI in education as one of its proposed priorities for discretionary grant programs. And in August, first lady Melania Trump launched the Presidential AI Challenge for students and teachers to solve problems in their schools and communities with the help of AI.

The Trump administration’s AI push comes amid its substantial cuts to K-12 education and research.

Still, Antoine said he’s “optimistic that really good things are going to come from the new focus on AI.”

AI Insights

Google’s top AI scientist says ‘learning how to learn’ will be next generation’s most needed skill

ATHENS, Greece — A top Google scientist and 2024 Nobel laureate said Friday that the most important skill for the next generation will be “learning how to learn” to keep pace with change as Artificial Intelligence transforms education and the workplace.

Speaking at an ancient Roman theater at the foot of the Acropolis in Athens, Demis Hassabis, CEO of Google’s DeepMind, said rapid technological change demands a new approach to learning and skill development.

“It’s very hard to predict the future, like 10 years from now, in normal cases. It’s even harder today, given how fast AI is changing, even week by week,” Hassabis told the audience. “The only thing you can say for certain is that huge change is coming.”

The neuroscientist and former chess prodigy said artificial general intelligence — a futuristic vision of machines that are as broadly smart as humans or at least can do many things as well as people can — could arrive within a decade. This, he said, will bring dramatic advances and a possible future of “radical abundance” despite acknowledged risks.

Hassabis emphasized the need for “meta-skills,” such as understanding how to learn and optimizing one’s approach to new subjects, alongside traditional disciplines like math, science and humanities.

“One thing we’ll know for sure is you’re going to have to continually learn … throughout your career,” he said.

The DeepMind co-founder, who established the London-based research lab in 2010 before Google acquired it four years later, shared the 2024 Nobel Prize in chemistry for developing AI systems that accurately predict protein folding — a breakthrough for medicine and drug discovery.

Greece’s Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, left, and Demis Hassabis, CEO of Google’s artificial intelligence research company DeepMind discuss the future of AI, ethics and democracy during an event at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, in Athens, Greece, Friday, Sept. 12, 2025. Credit: AP/Thanassis Stavrakis

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis joined Hassabis at the Athens event after discussing ways to expand AI use in government services. Mitsotakis warned that the continued growth of huge tech companies could create great global financial inequality.

“Unless people actually see benefits, personal benefits, to this (AI) revolution, they will tend to become very skeptical,” he said. “And if they see … obscene wealth being created within very few companies, this is a recipe for significant social unrest.”

Mitsotakis thanked Hassabis, whose father is Greek Cypriot, for rescheduling the presentation to avoid conflicting with the European basketball championship semifinal between Greece and Turkey. Greece later lost the game 94-68.

_

AI Insights

Artificial Intelligence Cheating – The Quad-City Times

Artificial Intelligence Cheating The Quad-City Times

Source link

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms1 month ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi