Education

A brewing discontent: disenfranchised graduates

In all the noise of various policy changes and studies showing that graduates with the right qualifications are still not securing jobs in their relevant fields, a fundamental question arises: why? What systemic hurdles require deeper examination, beyond reforms to post-study work rights?

Students who came for a world class education and global career pathways now face a different reality. Despite being qualified, capable, and often locally trained, many struggle to secure relevant jobs.

“I did everything right – top marks, internships, networking, but after graduation, I hit a wall. No one would sponsor me,” shared a postgraduate business student in Sydney.

“It’s like we were good enough to pay international fees, but not good enough to be hired or to stay,” said a nursing graduate in the UK.

Graduate underemployment is well documented across the Big Four. But the underlying reasons? Not so much.

We hear the statistics, but not enough about what is driving them. What explains the disconnect between qualifications and outcomes? Is it employer reluctance, lack of industry networks, inconsistent migration settings, or gaps in career readiness support? These questions deserve more scrutiny than they are currently being given.

In Australia, the Grattan Institute reports that nearly 50 percent of international graduates are working in low skilled jobs unrelated to their qualifications within six months of graduating . The 2023 Graduate Outcomes Survey found international students face higher unemployment and lower starting salaries compared to domestic peers. The graduate visa cohort remains underutilised, even as the National Skills Priority List flags urgent shortages in healthcare, engineering, information technology, and education.

In Canada, Statistics Canada found that five years after graduation, international students, especially from non-science and technology fields, earn significantly less than domestic graduates with comparable degrees. Labour market saturation, a surge in post-graduation work permit holders, and study permit caps have compounded the issue. Meanwhile, Canada continues to pursue ambitious immigration targets of more than 465,000 permanent residents per year to meet labour demands in critical sectors (IRCC Immigration Levels Plan 2023–2025).

In the UK, many international graduates on the Graduate Route are working in low wage, non-graduate roles due to limited sponsorship and unclear settlement pathways (Migration Observatory, 2023). This runs counter to the UK Shortage Occupation List, which highlights demand in science, education, and healthcare.

In the US, although the Optional Practical Training program provides a temporary work bridge, significant constraints remain. H-1B visa caps, permanent residency backlogs, and policy uncertainty have created a precarious pathway for international talent. Reports by NAFSA and the Cato Institute show high levels of post-study dropout, even as the US Bureau of Labor Statistics forecasts workforce shortages in software development, healthcare, and advanced manufacturing through 2031.

Policy reforms have focused heavily on access and visa entitlements, without addressing structural weaknesses in the education-to-employment pathway

Varsha Devi Balakrishna, Value Learning/Voyage

These patterns reveal a common thread: policy reforms have focused heavily on access and visa entitlements, without addressing structural weaknesses in the education-to-employment pathway. A system that attracts talent but fails to support its success is not sustainable.

Reimagining the international education offer: from transaction to transformation

If this is the reality international graduates face, then we must ask: what kind of experience are we really offering?

International education is not just an economic transaction. It is a social contract, and one that extends far beyond tuition payments, lecture halls, and graduation ceremonies. For decades, it has played a role in diplomacy, innovation, and people to people ties that stretch across generations and borders.

Graduates who succeed in host countries become ambassadors. Some return home to lead companies and shape public policy. Others stay and contribute to local innovation, workforce development, and demographic renewal. Either way, the benefits are mutual, but only if the system delivers on its promise.

When international graduates feel unsupported, underemployed, or unwelcome, the damage is not only personal. It erodes trust in the education to migration to employment promise that underpins the sector. It sends a signal to future cohorts that the promise made may not be kept.

What needs to change?

• Clear and consistent migration pathways tied to real labour demand

• Employer incentives to hire international graduates

• University led transition programs embedded early in the student journey

• Better data on outcomes, not just enrolments

• Active industry engagement beyond advisory roles

• Support to address employer hesitation and build confidence in graduate capability

“Give us a chance to prove ourselves. Most of us don’t want a handout, we just want a fair shot,” said information technology graduate in Melbourne.

If countries want to remain competitive, trusted, and future ready, international graduates must not be treated as short term contributors. They are long term partners in nation building, and it is time our systems recognised that.

Because today’s prospective students are asking sharper, more informed questions than ever before: “What percentage of graduates get a decent paying job in their field? Is there any data on graduate outcomes broken down by institution?”

These are not just questions. They are decision points. Institutions and destinations that can provide clear, transparent, and evidence-based answers will gain trust and remain attractive. Those that cannot will struggle to keep up.

The next era of international education is not just about attracting students. It is about delivering outcomes, building confidence, and designing a system that supports success well beyond graduation.

Education

Students, schools race to save clean energy projects in face of Trump deadline

Tanish Doshi was in high school when he pushed the Tucson Unified School District to take on an ambitious plan to reduce its climate footprint. In Oct. 2024, the availability of federal tax credits encouraged the district to adopt the $900 million plan, which involves goals of achieving net-zero emissions and zero waste by 2040, along with adding a climate curriculum to schools.

Now, access to those funds is disappearing, leaving Tucson and other school systems across the country scrambling to find ways to cover the costs of clean energy projects.

The Arizona school district, which did not want to impose an economic burden on its low-income population by increasing bonds or taxes, had expected to rely in part on federal dollars provided by the Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act, Doshi said.

But under HR1, or the “one big, beautiful bill,” passed on July 4, Tucson schools will not be able to receive all of the expected federal funding in time for their upcoming clean energy projects. The law discontinues many clean energy tax credits, including those used by schools for solar power and electric vehicles, created under the IRA. When schools and other tax-exempt organizations receive these credits, they come in the form of a direct cash reimbursement.

At the same time, Tucson and thousands of districts across the country that were planning to develop solar and wind power projects are now forced to decide between accelerating them to try to meet HR1’s fast-approaching “commence construction” deadline of June 2026, finding other sources of funding or hitting pause on their plans. Tina Cook, energy project manager for Tucson schools, said the district might have to scale back some of its projects unless it could find local sources of funding.

“Phasing out the tax credits for wind and solar energy is going to make a huge, huge difference,” said Doshi, 18, now a first-year college student. “It ends a lot of investments in poor and minority communities. You really get rid of any notion of environmental justice that the IRA had advanced.”

The tax credits in the IRA, the largest legislative investment in climate projects in U.S. history, had marked a major opportunity for schools and colleges to reduce their impact on the environment. Educational institutions are significant contributors to climate change: K-12 school infrastructure, for example, releases at least 41 million metric tons of emissions per year, according to a paper from the Annenberg Institute at Brown University. The K-12 school system’s buses — some 480,000 — and meals also produce significant emissions and waste. Clean energy projects supported by the IRA were helping schools not only to limit their climate toll but also to save money on energy costs over the long term and improve student health, advocates said.

As a result, many students, consultants and sustainability leaders said, they have no plans to abandon clean energy projects. They said they want to keep working to cut emissions, even though that may be more difficult now.

Related: Become a lifelong learner. Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter featuring the most important stories in education.

Sara Ross, cofounder of UndauntedK12, which helps school districts green their operations, divided HR1’s fallout on schools into three categories: the good, the bad and the ugly.

On the bright side, she said, schools can still get up to 50 percent off for installing ground source heat pumps — those credits will continue — to more efficiently heat schools. The network of pipes in a ground source pump cycles heat from the shallow earth into buildings.

In the “bad” category, any electric vehicle acquired after Sept. 30 of this year will not be eligible for tax credits — drastically accelerating the IRA’s phase-out timeline by seven years. That applies to electric school buses as well as electric vehicle charging stations at schools. EPA’s Clean School Bus Program still exists for two more years and covers two-thirds of the funding for all electric school buses districts acquire in that time. The remaining one-third, however, was to be covered by federal and state tax credits.

The expiration of the federal tax credits could cost a district up to $40,000 more per vehicle, estimated Sue Gander, director of the Electric School Bus Initiative run by the nonprofit World Resources Institute.

Related: So much for saving the planet. Climate jobs, and many others, evaporate for 2025 grads

Solar projects will see the most “ugly” effects of HR1, Ross said.

Los Angeles Unified School District is planning to build 21 solar projects on roofs, carports and other structures, plus 13 electric vehicle charging sites, as part of an effort to reduce energy costs and achieve 100 percent renewable energy by 2040. The district anticipated receiving around $25 million in federal tax credits to help pay for the $90 million contract, said Christos Chrysiliou, chief eco-sustainability officer for the district. With the tight deadlines imposed by HR1, the district can no longer count on receiving that money.

“It’s disappointing,” Chrysiliou said. “It’s nice to be able to have that funding in place to meet the goals and objectives that we have.”

LAUSD is looking at a small portion of a $9 billion bond measure passed last year, as well as utility rebates, third-party financing and grants from the California Energy Commission, to help make up for some of the gaps in funding.

Many California State University campuses are in a similar position as they work to install solar to meet the system’s goal of carbon neutrality by 2045, said Lindsey Rowell, CSU’s chief energy, sustainability and transportation officer.

Tariffs on solar panel materials from overseas and the early sunsetting of tax credits mean that “the cost of these projects are becoming prohibitive for campuses,” Rowell said.

Sweeps of undocumented immigrants in California may also lead to labor shortages that could slow the pace of construction, Rowell added. “Limiting the labor force in any way is only going to result in an increased cost, so those changes are frightening as well,” she said.

New Treasury Department guidance, issued Aug. 15, made it much harder for projects to meet the threshold needed to qualify for the tax credits. Renewable energy projects previously qualified for credits once a developer spent 5 percent of a project’s cost. But the guidelines have been tightened — now, larger projects must pass a “physical work test,” meaning “significant physical labor has begun on a site,” before they can qualify for credits. With the construction commencement deadline looming next June, these will likely leave many projects ineligible for credits.

“The rules are new, complex [and] not widely understood,” Ross said. “We’re really concerned about schools’ ability to continue to do solar projects and be able to effectively navigate these new rules.”

Schools without “fancy legal teams” may struggle to understand how the new tax credit changes in HR1 will affect their finances and future projects, she added.

Some universities were just starting to understand how the IRA tax credits could help them fund projects. Lily Strehlow, campus sustainability coordinator at the University of Wisconsin, Eau-Claire, said the planning cycle for clean energy projects at the school can take ten years. The university is in the process of adding solar to the roof of a large science building, and depending on the date of completion, the project “might or might not” qualify for the credits, she said.

“At this point, everybody’s holding their breath,” said Rick Brown, founder of California-based TerraVerde Energy, a clean energy consultant to schools and agencies.

Brown said that none of his company’s projects are in a position where they’re not going to get done, but the company may end up seeing fewer new projects due to a higher cost of equipment.

Tim Carter, president of Second Nature, which supports climate work in education, added that colleges and universities are in a broader period of uncertainty, due to larger attacks from the Trump administration, and are not likely to make additional investments at this time: “We’re definitely in a wait and see.”

Related: A government website teachers rely on is in peril

For youth activists, the fallout from HR1 is “disheartening,” Doshi said.

Emma and Molly Weber, climate activists since eighth grade, said they are frustrated. The Colorado-based twins, who will start college this fall, helped secure the first “Green New Deal for Schools” resolution in the nation in the Boulder Valley School District. Its goals include working toward a goal of Zero Net Energy by 2050, making school buildings greener, creating pathways to green jobs and expanding climate change education.

“It feels very demoralizing to see something you’ve been working so hard at get slashed back, especially since I’ve spoken to so many students from all over the country about these clean energy tax credits, being like, ‘These are the things that are available to you, and this is how you can help convince your school board to work on this,’” Emma Weber said.

The Webers started thinking about other creative ways to pay for the clean energy transition and have settled on advocating for state-level legislation in the form of a climate superfund, where major polluters in a community would be responsible for contributing dollars to sustainability initiatives.

Consultants and sustainability coordinators said that they don’t see the demand for renewable energy going away. “Solar is the cheapest form of energy. It makes sense to put it on every rooftop that we can. And that’s true with or without tax credits,” Strehlow said.

Contact editor Caroline Preston at 212-870-8965, via Signal at CarolineP.83 or on email at preston@hechingerreport.org.

This story about tax credits was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

Education

Maine Monitor: ‘Building the plane as we’re flying it’: How Maine schools are using generative AI in the classroom

By Kristian Moravec of the Maine Monitor

One platform, MagicSchool, has more than 8,500 educator accounts in Maine. As teachers and students increasingly turn to these tools, some school districts are working to codify guidelines for ethical use.

In Technology Director Mike Arsenault’s office at the Yarmouth School Department, papers and boxes sat on his desk — some of it swag from the tech company MagicSchool, one of several artificial intelligence programs the district is now using.

The AI platform, which was designed for educators, offers tools like a lesson planner, letter of recommendation producer, Individualized Education Plan drafter and even a classroom joke writer. The district pays about $10,000 a year for a MagicSchool enterprise package, and Arsenault said that his favorite element is the “Make it Relevant” tool, which prompts teachers to describe their class and what they’re studying and then generates activities that tie student interests to the subject.

“Because the question that students have asked forever is ‘why are we learning this,” Arsenault said, explaining that students should have clear examples of how lessons are useful outside of the classroom. “That’s something that AI is really good at.”

The district is one of many across Maine that is increasingly using AI in its classrooms. Some, like Yarmouth, have established formal AI guidelines. Others have not. MagicSchool told The Monitor that it has around 8,500 educator accounts active in Maine. This would equate to more than half of the state’s public school teachers, though anyone can sign up for a free educator account.

The state Department of Education does not yet have data on how many teachers or school districts are using AI, but said that based on the level of interest schools have for AI professional development, its use is widespread. The department is conducting a study to better understand how schools are integrating the new technology and hopes to release data next spring, according to a spokesperson.

The use of generative AI — a type of artificial intelligence that generates new text, images or other content, such as the technology used in ChatGPT — is prompting a growing debate in education. Critics see it as a tool that decreases critical thinking and helps students cheat, while advocates see it as a fixture that students must learn how to use ethically.

A majority of teachers across the country are growing familiar with AI for either personal or school use, and suspect that their students are using it widely as well, according to a 2024 study by the Center for Democracy and Technology.

As AI changes come at breakneck speed, leaders are pushing for its controlled use in schools. Roughly half of states have some form of AI guidance in place, according to the Sutherland Institute.

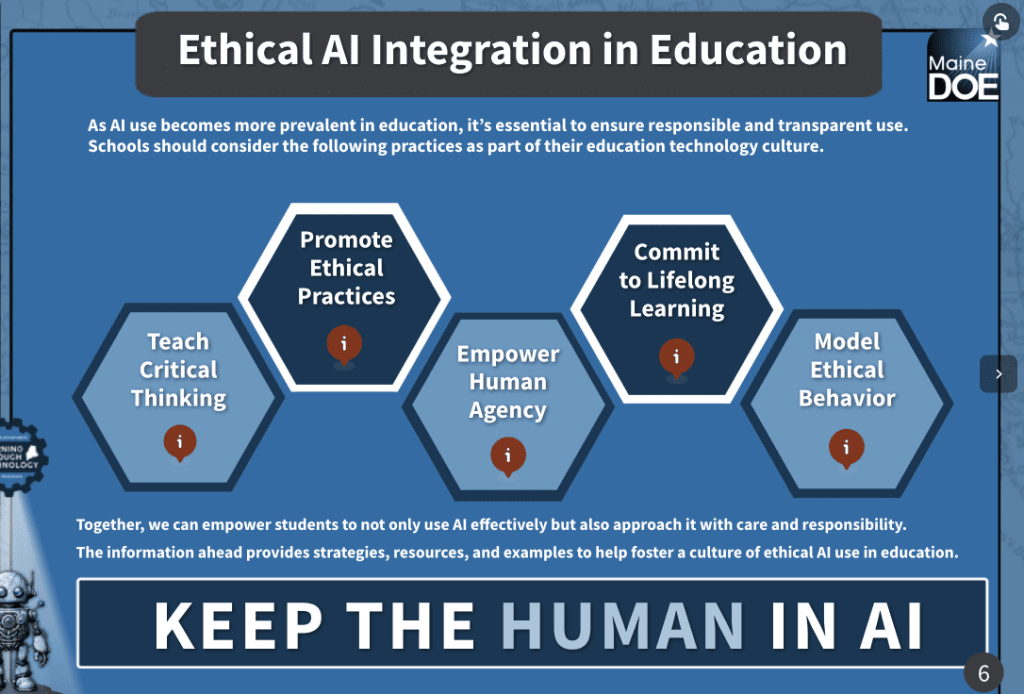

Maine introduced an interactive AI guidance toolkit earlier this year, which walks educators through ways they can integrate AI in the classroom from pre-Kindergarten to 12th grade and the questions to consider when doing so. Students in pre-Kindergarten through second grade could “use AI to generate art and have students collboarate [sic] to create a shared image,” according to the guidance, or high school students could “explore cybersecurity principles through ethical hacking simulations.”

The guidance encourages teachers to “keep the human in AI” by stopping to ask if its use is appropriate for the task, monitoring for accuracy and noting how AI was used.

The governor’s office launched a state AI Task Force last year to prepare Maine for the “opportunities and risks likely to result from advances in AI” in private industries, education and government. The task force’s education subgroup has met three times this year, and plans to release a report on AI use in Maine this fall.

For Yarmouth Superintendent Andrew Dolloff, it is important to help students tackle the increasingly popular technology in a safe environment. The district adopted its first set of AI guidelines last year, which emphasize that staff should be transparent and cite any use of generative AI, ensure student data privacy is protected, be cautious of bias and misinformation and understand the technology “as an evolving tool, not an infallible source.”

“AI is here to stay. It’s part of our lives. We’re all using it as adults on a daily basis. Sometimes without even knowing it or realizing that it’s AI,” Dolloff said. “So we changed our stance pretty quickly to understand that rather than trying to ban AI, we needed to find ways to effectively use it, and allow students to use it appropriately to expand their learning.”

Maine School Administrative District 75 — which serves Harpswell, Topsham, Bowdoin and Bowdoinham — adopted an AI policy earlier this year, though some school board members were hesitant to approve the policy over concerns that generative AI can help students cheat and produce misinformation, The Harpswell Anchor reported.

Some school districts, such as Regional School Unit 22, which serves Hampden, Newburgh, Winterport and Frankfort, have launched internal committees to guide AI use, while others, such as MSAD 15 in Gray and New Gloucester, are pursuing policies in the wake of controversy.

Earlier this year, a student at MSAD 15 alleged that a teacher graded a paper using AI, WGME reported. Superintendent Chanda Turner told The Maine Monitor that teachers are piloting programs that use AI to give feedback on papers, but are not using it to issue grades. The school board will be working on an AI policy for the district this school year, she said.

Nicole Davis, an AI and emerging technology specialist with the DOE who helped write the state guidelines, estimates that over 40 school districts in Maine have requested professional development for AI, and expects that interest will grow. She noted that guiding AI use can be a challenge, as the technology changes so quickly.

“We’re building the plane as we’re flying it,” Davis said.

‘I was stunned’

Julie York, a computer science teacher at South Portland High School, has long incorporated new technology into her teaching, and has found generative AI tools like ChatGPT and Google Gemini to be “incredibly useful.” She has used it to create voiceovers for presentations when she was tired, to help make rubrics and lesson plans and to build a chatbot that can answer questions during class, which she says helps her balance the amount of time she spends with each student.

“I don’t think there’s any educator who wakes up in the morning, and is like, ‘oh my god, I hope I can make a rubric today.’ I just don’t think you’re going to find any,” she said. “And there’s no teacher who isn’t tired.”

She vets all the AI resources she uses before integrating them into her work, and has discussions with her students about when using AI is appropriate. Student use is guided by the traffic light model: if an assignment is green, students can use AI under the guidance of a teacher, if it’s yellow that means limited use with teacher permission, and red means no AI. She makes these determinations depending on the type of assessment. If she wants them to be able to read code and understand what it does, for instance, then AI cannot be used. But if a student is coding a computer program, she said, then AI can be a useful tool.

AI can also help teachers accommodate diverse needs, York said, explaining that students who have trouble speaking in front of a class could use text-to-voice software to produce voiced-over videos. The district’s students speak several different languages, and she used AI to help her create an app that translates her speech into multiple languages while she’s teaching. It took her about an hour to make.

“I just sat there stunned at my computer. Just stunned,” York recalled.

Maine Education Association President Jesse Hargrove said that teachers are exploring the evolving AI landscape alongside their students, noting that AI can help create steps for science projects, or detect whether students cheated.

“I think it’s being used as a partner in the learning, but not a replacement for the thinking,” he said.

MEA’s approach to AI is guided by the National Education Association’s policy, which emphasizes putting educators at the center of education. However, Hargrove said that MEA does not have a stance on whether or not districts should adopt AI.

“We believe that AI should be enhancing the educational experience rather than replacing educators,” he said.

‘Click. Boom. Done.’

Maine’s AI guidance emphasizes that teachers should have clear expectations for AI use in the classroom. It recommends being specific about grade levels, lesson times, content and general student needs when prompting services like ChatGPT to generate lesson plans.

The state told The Monitor it does not recommend any AI tools in particular. Instead, the DOE said it encourages schools to research tools and consider data security, privacy and use.

But its guidance toolkit references a handful of specific programs. MagicSchool and Diffit are listed as tools that can help with accessibility in the classroom. Almanack, MagicSchool and Canva are noted as tools that can help boost student engagement.

The types of AI tools that educators use vary depending on their needs, Davis said, but there seem to be five tools that can assess papers, create study materials and help build curriculums that schools are turning to the most: Diffit, Brisk, Canva, MagicSchool and School AI.

“That batch of essays that’s looming? Brisk will help you grade them before the bell rings,” Brisk’s website reads. “Need a lesson plan for tomorrow? Click. Boom. Done.”

Use of these platforms is regulated by legal parameters for student data safety, such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and Maine’s Student Information Privacy Act. Technology companies must sign a data privacy agreement for the states in which they plan to operate. Maine’s data privacy agreement with MagicSchool, for instance, covers nine other states and sets guardrails for student data collection such as leaving ownership and control of data to “local education agencies.”

Some education-based AI companies also have their own parameters in place. MagicSchool, which was founded by former educator Adeel Khan, requires teachers to sign a best practices agreement, reminds them not to enter personal student information into AI prompts like an Individual Education Plan generator, and claims it erases any student information that gets entered into its system.

“We’re always iterating and trying to make things safer as we go,” Khan said, citing MagicSchool’s favorable rating for privacy on Common Sense Media, an organization that rates technology and digital media for children.

The federal government has also pushed for the use of AI in schools. In the spring, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to promote AI in education, and the federal Department of Education has since published a letter encouraging the use of grant funding to “support improved outcomes for learners through responsible integration of artificial intelligence.”

In late August, First Lady Melania Trump launched the Presidential AI Challenge: asking students to “create AI-based innovative solutions to community challenges.”

The White House is also running a pledge campaign, “Investing in AI Education,” asking technology companies to commit resources like funding, education materials, technology, professional development programs and access to technical expertise to K-12 students, teachers and families for the next four years. More than 100 entities have signed on, including MagicSchool.

In Maine, the DOE is working on broader AI professional development for teachers, with plans to launch a pilot course based on the state’s AI guidance toolkit, potentially as soon as this fall.

As Yarmouth starts the new school year, Arsenault said that AI should be integrated with the goal of preparing students for a future that will be filled with AI.

“We can do what many schools do and ignore it, or we can address it,” Arsenault said. “And if we address it with our students, we have the ability to frame the discussion on how it’s used, and have discussions with our students about how we want to see it used in our classrooms.”

Education

AI in the classroom – the upending of traditional education

On a recent episode of the New York Times’ Hard Fork podcast, I was startled to hear about an “AI-first” school that has used AI to reduce academic teaching time to a mere two hours per day and has redeployed teachers to be mentors and guides, rather than deliverers of content, policing, and grading.

What happens after the two-hour academic class? Lots of fun, apparently – collaboration games, motivation exercises, and life skills activities. The school boasted that students are scoring in the 99th percentile nationally for its core curriculum. Oh, and no homework. Ever.

We’ll get back to the veracity of these claims in a moment. Most of the discussion about AI and students has been around the use of GenAI to circumvent the hard work of doing homework and essays and reading, by passing that job over to a chatbot, which generally does fine work on their behalf – at least if you are a student looking to shirk responsibilities and don’t object to a bit of plagiarism.

Schools and teachers, unsurprisingly, were rather irritated by this and instituted various fightback campaigns ranging from threats to AI bans to punishments to technology-based chatbot plagiarism detectors (the latter now generally agreed to be hopelessly inadequate).

Some educators are now realising that this is all a waste of time. Students are going to use GenAI wherever they can: at school, at home, in the bathroom. One current study has 63% of US high-school students using AI in ways that they know contradict school policy. There is no way to stop it, and it is becoming apparent that perhaps it should be encouraged within carefully designed guardrails.

And so a new crop of education initiatives is blooming where the AI designs the course plan, does the teaching, the monitoring, the personalised assistance, the remedial support (where appropriate), as well as the evaluations and grading. This leaves the teacher free to concentrate on softer skills like coaching and mentorship, making the school a more joyous and expansive experience for both students and teachers.

How is it going? The school I mentioned earlier is Alpha Schools, which now operates three campuses in the US. It is one of the better-known AI-first ventures. Its model is mixed-age microschools using adaptive platforms so students “learn 2x in 2 hours,” then spend afternoons on projects, mentorship, and life skills.

Deliberately disruptive

The idea is deliberately disruptive – take the tedium out of repetitive content acquisition and give time back for exploration. Independent observers and critics are understandably sceptical of headline ratios such as “2 times faster” learning; some commentators have flagged that such claims need careful scrutiny and peer-reviewed evidence.

In the podcast co-founder MacKenzie Price enthusiastically proclaims:

“We practise what’s called the Pomodoro Technique. So, kids are basically doing like 25 minutes of focused attention in the core academics of maths, reading, language, and science. They get breaks in between, and then by lunchtime, academics are done for the day and it’s time to do other things.

“So in the afternoon is where it gets really exciting because when kids don’t have to sit at a classroom desk all day long, just grinding through academics, we instead use that time for project-based, collaborative life-skills projects. These are workshops that are led by our teachers – we call them guides – and they’re learning skills like entrepreneurship and financial literacy and leadership and teamwork and communication and socialisation skills.”

There has been some grumbling about her claims. They are self-reported numbers, and a couple of parents have been critical. Also, the school is not cheap, so the results would certainly show some selection bias. On the other hand, they do not reject children with poor academic track records, which is more than can be said for other private schools.

Pushed the conversation

Still, places like Alpha have pushed the conversation from “can we use AI in classrooms?” to “how radically should we reorganise the school day around it?” – and that question is exactly the kind of policy and practice debate we need.

There are other schools too, like the private David Game College in London, currently piloting an AI-first teaching curriculum for 16-year-olds, which looks very similar to Alpha Schools, with similar sterling results. But there are only 16 students in the pilot, so the jury remains out.

What about the public-school system? Is AI just for the rich? Turns out, no. There is an impressive case study in Putnam County Public Schools in Tennessee. Facing a severe shortage of computer science teachers, the school district partnered with an AI platform called Kira Learning.

What happened next was a true testament to the power of a good hybrid model: 1,200 students enrolled, and every single one of them passed the course – which would be remarkable in any subject, let alone computer science. This wasn’t “AI-first” in the Alpha School sense. It was “AI-for-all,” a tool that levelled the playing field and brought a vital skill to students who might otherwise have missed out. The teachers weren’t replaced; they became “facilitators,” freeing them from grading and lesson planning to focus on student engagement.

It is not only students that benefit. Consider AcademIQ in India, an AI-powered educational application designed to revolutionise the learning experience for teachers, students, and parents, particularly in multilingual and low-resource classrooms. Launched in 2023, the platform is India’s first to be built around the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020.

Simplicity

The platform’s primary appeal lies in its simplicity. It offers over 150 AI tools, most notably an “instant NEP-aligned lesson plan generator” that requires no prompts or technical expertise. Teachers simply select a class, subject, and topic to receive a complete lesson plan in seconds. This is a direct response to a major pain point for educators; testimonials indicate the platform can reduce weekly lesson-planning time by several hours, freeing up teachers to focus on student engagement.

What then of pedagogy – the art and science of teaching? Universities, which have a long heritage in teacher training, are notoriously slow to change curricula. If it is true that everything except the interpersonal roles of mentorship, coaching, and guidance will be outsourced to much more efficient AI teachers, what then should be the requirements of a teaching degree or certificate? It is not clear that anyone has wrestled with this question sufficiently, particularly given AI’s dizzying rate of improvement.

For those teachers terrified of these coming changes, but resigned to the imminent primacy of AI tutors, there is this comfort – no more lesson plans, no more grading, no more one-size-fits-all. Just the nobler task of shaping the critical human traits of motivation, confidence, enthusiasm, collaboration, and childhood curiosity.

That sounds much more satisfying than the old way.

[Image: Photo by Element5 Digital on Unsplash]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms4 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi