Tools & Platforms

AI Fears Become Reality In The Tech Industry

This is a published version of Forbes’ Careers Newsletter. Click here to subscribe and get it in your inbox every Tuesday.

Fears of AI taking over jobs is already becoming a reality in tech.

Fears of artificial intelligence costing people their jobs are already proving to be true.

Or at the very least, CEOs are now admitting to the technology’s impact as AI-related layoffs ramp up, especially in the tech industry, reports Forbes’ Richard Nieva. Fiverr CEO Micha Kaufman is just the latest to say out loud that AI is already a threat to all kinds of jobs—including his. In an April memo to his 1,200 employees, he wrote: “AI is coming for your jobs. Heck, it’s coming for my job too.”

“I hear the conversation around the office. I hear developers ask each other, ‘Guys, are we going to have a job in two years?’” Kaufman tells Forbes now. “I felt like this needed validation from me—that they aren’t imagining stuff.”

He joins the likes of Andy Jassy at Amazon, Anthropic’s Dario Amodei and Shopify’s Tobi Lutke in admitting that AI will replace humans in white-collar jobs, some going as far as predicting a “white-collar bloodbath.”

The impacts are already being felt, particularly for young coders and entry-level workers. The total number of employed entry-level developers from ages 18 to 25 has dropped “slightly” since 2022, after the launch of ChatGPT, said Ruyu Chen, a postdoctoral fellow at the Digital Economy Lab of Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered AI.

But not everything can, or should, be automated just yet. Take the buy-now-pay-later firm Klarna, for example, which last year slashed its workforce by 40% in part to the company’s investments in AI. A year later, it launched a massive recruiting push for human customer service agents. “We have noticed that in a world where everything is automated,” Klarna spokesperson Clare Nordstrom told Forbes, “people put a premium on the human experience.”

Happy reading, and hope you have a lovely week!

WORK SMARTER

Practical insights and advice from Forbes staff and contributors to help you succeed in your job, accelerate your career and lead smarter.

Why mastering “systems-thinking” skills could protect your job from AI.

What to do when someone is hired above you.

Amid all the hype, here’s why you may not need an AI agent.

TOUCH BASE

News from the world of work.

Looking for lower costs, different lifestyles and less toxic politics, more Americans are considering retiring abroad. In its annual Best Places To Retire Abroad, list, Forbes ranked the 24 countries and 96 spots that could make the most sense for retirees looking outside the U.S.

Beloved office snacks might soon be a thing of the past, thanks to Congress. Despite luring workers back into the office with the promise of free food, employers will no longer be able to deduct the cost of the food they provide for their employees as part of President Donald Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill. The only exceptions: restaurants and the Alaskan fishing industry.

One seemingly innocuous kiss cam at a Boston Coldplay concert has caused quite the workplace drama at tech startup Astronomer, pushing the company into the internet’s spotlight. Former CEO Andy Byron stepped down after being caught embracing chief people officer Kristin Cabot at the concert, while the company’s cofounder and chief product officer Pete DeJoy has stepped up as interim chief executive.

More than half of U.S. companies are looking to pare back on health benefits as weight loss spending soars, according to Reuters. Increased cost sharing means employers could raise deductibles or maximum out-of-pocket costs, or even look beyond traditional pharmacy benefit managers, which act as middlemen between patients and insurers.

NUMBER TO NOTE

9.3%

That’s how much of the WNBA’s league revenue is allocated to player salaries, significantly less than the 49% to 51% players in the NBA get. The significant salary disparity, which has star players like Caitlin Clark earning just $76,535 according to MarketWatch, has come to light after WNBA players wore a black shirt that read “Pay us what you owe us” during last weekend’s All-Star Game warm-ups.

VIDEO

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2DYvvBPRx4

Could Tesla’s Board Oust Elon Musk?

QUIZ

What bank joined JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs in cracking down on junior bankers accepting early private equity job offers?

A. Bank of America

B. Barclays

C. Citi

D. Morgan Stanley

Check if you got it right here.

Tools & Platforms

AI “Can’t Draw a Damn Floor Plan With Any Degree of Coherence” – Common Edge

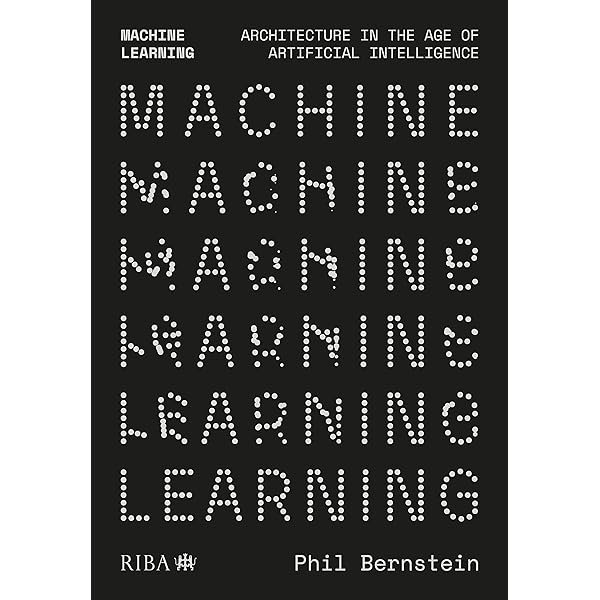

Recently I began interviewing people for a piece I’m writing about “Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Architecture,” a ludicrously broad topic that will at some point require me to home in on a particular aspect of this rapidly changing phenomenon. Before undertaking that process, I spoke with some experts, starting with Phil Bernstein, an architect, educator, and longtime technologist. Bernstein is deputy dean and professor at the Yale School of Architecture, where he teaches courses in professional practice, project delivery, and technology. He previously served as a vice president at Autodesk, where he was responsible for setting the company’s AEC vision and strategy for technology. He writes extensively on issues of architectural practice and technology, and his books include Architecture | Design | Data — Practice Competency in the Era of Computation (Birkhauser, 2018) and Machine Learning: Architecture in the Era of Artificial Intelligence (2nd ed., RIBA, 2025). Our short talk covered a lot of ground: the integration of AI into schools, its obvious shortcomings, and where AI positions the profession.

PB: Phil Bernstein

MCP: Martin C. Pedersem

You’re actively involved in the education of architects, all of them digital natives. How is AI being taught and integrated into the curriculum?

I was just watching a video with a chart that showed how long it took different technologies to get to 100 million users: the telephone, Facebook, and DeepSeek. It was 100 years for the phone, four years for Facebook, two months for Deepseek. Things are moving quickly, almost too quickly, which means you don’t have a lot of time to plan and test pedagogy.

We are trying to do three things here. One, make sure that students understand the philosophical, legal, and disciplinary implications of using these kinds of technologies. I’ll be giving a talk to our incoming students as part of their orientation about the relationship between generative technology, architectural intellectual property, precedent, and academic integrity. And why you’re here to learn: not how to teach algorithms to do things, but to do them yourself. That’s one dimension.

The second dimension is, we’re big believers in making as much technology as we can support and afford available to the students. So we’ve been working with the central campus to provide access to larger platforms, and to make things as available and understandable as we possibly can.

Thirdly, in the classroom, individual studio instructors are taking their own stance on how they want to see the tools used. We taught a studio last year where the students tried to delegate a lot of their design responsibility to algorithms, just to see how it went, right?

Control. You lose a lot of design autonomy when you delegate to an algorithm. We’ve also been teaching a class called “Scales of Intelligence,” which tries to look at this problem from a theory, history, and technological evolution perspective, delving into the implications for practice and design. So it’s a mixed bag of stuff, very much a moving target, because the technology evolves literally during the course of a semester.

I am a luddite, and even I can see it improve in real time.

It’s getting more interesting, minute to minute, very shifting ground. I was on the Yale Provost’s AI Task Force, which was the faculty working group formed a year ago that tried to figure out what we’re doing as a university. Everybody was in the same boat, it’s just some of the boats were tiny, paper boats floating in the bathtub, and some of them were battleships—like the medical school, with more than 50 AI pilots. We’re trying to keep up with that. I don’t know how good a job we’re doing now.

What’s your sense in talking to people in the architecture world? How are they incorporating AI into their firms?

It’s difficult to generalize, because there are a lot of variables: your willingness to experiment, a firm’s internal capabilities, the availability of data, and degree of sophistication. I’ve been arguing that because this technology is expensive and requires a lot of data and investment to figure it out, the real innovation will happen in the big firms.

Everybody’s creating marketing collateral, generating renderings, all that stuff. The diffusion models and large language models, the two things that are widely available—everybody is screwing around with that. The question is, where’s the innovation? And it’s a little early to tell.

The other thing you’ve got to remember is the basic principle of technology adoption in the architectural world, which is: When you figure out a technological advantage, you don’t broadcast it; you keep your advantage to yourself for as long as you can, until somebody else catches up. A recent example: It’s not like there were firms out there helping each other adopt building information modeling.

I guess it’s impossible to project where all this goes in three or five years?

I don’t know. The reigning thesis—I’m simplifying this—is that you can build knowledge from which you can reason inferentially by memorizing all the data in the world and breaking it into a giant probability matrix. I don’t happen to think that thesis is correct. It’s the Connectionists vs. the Symbolic Logic people. I believe that you’re going to need both of these things. But all the money right now is down on the Connectionists, the Sam Altman theory of the world. Some of these things are very useful, but they’re not 100% reliable. And in our world, as architects, reliability is kind of important.

Again, we can’t predict the pace of this, but it’s going to fundamentally change the role of the architect. How do you see that evolving as these tools get more powerful?

Why do you say that? There’s a conclusion in your statement.

I guess, because I’ve talked to a few people. They seem to be using AI now for everything but design. You can do research much faster using AI.

That’s true, but you better check it.

I agree, but isn’t there inevitably a point when the tools become sophisticated enough where they can design buildings?

So, therefore … what?

Where does that leave human architects?

I don’t know that it’s inevitable that machines could design entire buildings well …

It would seem to me that we would be moving toward that.

The essence of my argument is: there are many places where AI is very useful. Where it begins to collapse is when it’s operating in a multivalent environment, trying to integrate multiple streams of both data and logic.

Which would be virtually any architecture project.

Exactly. Certain streams may become more optimized. For instance: If I were a structural engineer right now, I’d be worried, because structural engineering has very clear, robust means of representation, clear rules of measurement. The bulk of the work can be routinized. So they’re massively exposed. But these diffusion models right now can’t draw a damn floor plan with any degree of coherence. A floor plan is an abstraction of a much more complicated phenomenon. It’s going to be a while before these systems are able to do the most important things that architects do, which is make judgments, exercise experience, make tradeoffs, and take responsibility for what they do.

Where do you fall on the AI-as-job-obliterator, AI-as-job-creator debate?

For purposes of this discussion, let’s stipulate that artificial general intelligence that can do anything isn’t in the foreseeable future, because once that happens, the whole economic proposition of the world collapses. When that happens, we’re in a completely different world. And that won’t just be a problem for architects. So, if that’s not going to happen any time soon, then you have two sets of questions. Question one: In the near term, does AI provide productivity gains in a way that reduces the need for staff in an architect’s office?

That may be the question I’m asking …

OK, in the near term, maybe we won’t need as many marketing people. You won’t need any rendering people, although you probably didn’t have those in the first place. But let me give you an example from an adjacent discipline that’s come up recently. It turns out that one thing that these AIs are supposed to be really good at is writing computer code. Because computer code is highly rational. You can test it and see if it works. There’s boatloads of it on the internet as training data in well organized locations, very consistently accessible—which is not true of architectural data, by the way.

It turns out that many software engineering companies who had decided to replace their programmers with AIs are now hiring them back because the code-generating AIs are not reliable enough to write good code. And then you intersect that with the problem that was described in a presentation I saw a couple of months ago by our director of undergraduate studies in computer science, [Theodore Kim,] who said that so many students are using AI to generate code that they don’t understand how to debug the code once it’s written. He got a call from the head of software engineering for EA, who said, “I can’t hire your graduates because they don’t know how to debug.” And if it’s true here, I guarantee you, it’s true everywhere across the country. So you have a skill loss.

Then there’s what I would call the issue of the luddites. The [original] Luddites didn’t object to the weaving machines, per se, but they objected to the fact that while they were waiting for a job in the loom factory, they didn’t have any work. Because there was this gap between when humans get replaced by technology and when there are new jobs for them doing other things: you lost your job plowing that cornfield with a horse because there’s a tractor now, but you didn’t get a job in the tractor factory, somebody else did. These are all issues that have to be thought about.

It seems like a lot of architects are dismissive because of what AI can’t do now, but that seems silly to me, because I’m seeing AI enabling things like transcriptions now.

But transcriptions are so easy. I do not disagree that, over time, these algorithms will get more capable doing some of the things that architects do. But if we get to the point where they’re good enough to literally replace architects, we’re going to be facing a much larger social problem.

There’s also a market problem here that you need to be aware of. These things are fantastically expensive to build, and architects are not good technology customers. We’re cheap and steal a lot of software—not good customers for multibillion-dollar investments. Maybe, over time, someone builds something that’s sophisticated enough, multimodal enough, that can operate with language, video, three-dimensional reasoning, analytical models, cost estimates, all those things that architects need. But I’m not concerned that that’s going to happen in the foreseeable future. It’s too hard a problem, unless somebody comes up with a way to train these things on much skinnier data sets.

That’s the other problem: all of our data is disaggregated, spread all over the place. Nobody wants to share it, because it involves risk. When the med school has 33,000 patients enrolled in a trial, they’re getting lots of highly curated, accurate data that they can use to train their AIs. Where’s our accurate data? I can take every Revit model that Skidmore, Owings & Merrill has ever produced in the history of their firm, and it’s not nearly enough data to train an AI. Not nearly enough.

And what do you think AI does to the traditional business model of architecture, which has been under some pressure even before this?

That’s always been under pressure. It depends on what we as a profession decide. I’ve written extensively about this. We have two options. The first option is a race to the bottom: Who can use AI to cut their fees as much as possible? Option number two, value: How do we use AI to do a better job and charge more money? That’s not a technology question, it’s a business strategy question. So if I’ve built an AI that is so good that I can promise a client that x is going to happen or y is going to happen, I should charge for that: “I’m absolutely positive that this building is going to produce 23% less carbon than it would have had I not designed it. Here’s a third party that can validate this. Write me a check.”

Featured image courtesy of Easy-Peasy.AI.

Tools & Platforms

Need A Job? ChatGPT Becomes LinkedIn Meets AI Tutor And Recruiter

Need a Job? OpenAI’s ChatGPT Becomes LinkedIn Meets AI Tutor and Recruiter (Photo by Tomohiro Ohsumi/Getty Images)

Getty Images

ChatGPT is stepping into a job market that has been struggling to find its footing. Millions of job seekers complain that sending out resumes feels like shouting into a void, while employers admit they cannot easily separate real skills from inflated buzzwords.

Per Resume Genius, as of July 2025, there were 7 million unemployed individuals competing for 7.7 million job openings, marking the first time since 2021 that job seekers outnumbered available positions. At the same time, workers worry about being displaced by the very technologies reshaping business, particularly artificial intelligence.

Into this environment comes OpenAI with a potentially disruptive concept: a jobs platform driven by ChatGPT. Reports from CNBC suggest the company is preparing to launch a hiring and certification ecosystem that could rival Microsoft’s LinkedIn. If successful, it could transform how the job market functions.

What ChatGPT May Bring to Hiring

Think of the vision as LinkedIn meets AI tutor meets recruiter—but powered by ChatGPT.

This isn’t a traditional job board. ChatGPT may integrate three core features.

First, skill certification: through ChatGPT’s study and learning modes, people could earn AI-validated micro-credentials, from AI fluency to prompt engineering, in days rather than years.

Second, AI-powered matching: instead of sifting through keyword-stuffed listings, ChatGPT might match users to roles based on demonstrated ability, not just past job titles.

ChatGPT could reshape hiring and skills training (Photo by Leon Neal/Getty Images)

Getty Images

Third, up-skilling: if candidates fall short of a requirement, the same AI could guide them through learning modules to get them up to speed.

Imagine logging into OpenAI’s platform and asking ChatGPT to show you open Web3 marketing roles. The AI identifies relevant openings and spots gaps in your skills—maybe in blockchain fundamentals, crypto ecosystems, or decentralized identity. It then suggests tailored training modules, and once completed, issues on-chain credentials that employers can verify. With these portable, tamper-proof certifications, ChatGPT may match you with hiring managers looking for precisely those skills—and might even facilitate scheduling interviews.

Pretty awesome promise for job seekers.

Why Timing May Be Critical for ChatGPT

Today’s labor market is fractured.

Applications stack up unanswered. Employers struggle to gauge real capability. Career shifters and those laid off can’t easily prove what they know. Meanwhile, workers feel vulnerable amid fast-moving AI disruption. OpenAI’s approach—with training and certification built into job matching—shifts ChatGPT from being seen as a threat to becoming a tool for empowerment.

The ambition is striking.

OpenAI is embedding certification directly into ChatGPT, allowing anyone to prepare and test within the app’s Study mode. The company has set a bold goal of certifying 10 million Americans by 2030, starting with launch partners like Walmart.

Walmart, the largest private employer in the world, announced it will provide the new no-cost OpenAI certification to its 2 million U.S. associates beginning next year as part of its up-skilling efforts. The program is designed to equip workers with essential AI skills and support their growth as technology becomes a larger part of daily work.

How ChatGPT Could Impact Job Seekers and Employers

For individuals, the implications could be life-changing. Many job seekers feel stuck without the right degree or with resumes filtered out by automated systems. Someone self-taught in generative AI may finally get credentials that employers trust. A mid-career worker facing layoffs could retrain quickly and prove new capabilities. International applicants might gain universally recognized credentials—all contributing to a fairer job market.

For employers, the promise is compelling. Hiring is expensive and uncertain. Resumes don’t always tell the truth, and turnover drains resources. If ChatGPT can certify skills and match candidates with greater precision, hiring could become faster, cheaper, and more confident—even introducing new pools of overlooked talent.

ChatGPT, Microsoft, and the Future of Work

The strategic dynamics are worth noting. Microsoft is OpenAI’s largest backer and also owns LinkedIn. On the one hand, OpenAI’s move may compete with its own investor’s platform. On the other, there may be collaboration—imagine ChatGPT-based certifications flowing into LinkedIn profiles. Regardless, wider AI literacy drives demand for Microsoft’s cloud and AI services, making this ecosystem too valuable to ignore.

Of course, there are risks.

Will this be a good partnership for OpenAI and Microsoft’s Linkedin? (Photo by Lionel BONAVENTURE / AFP) (Photo by LIONEL BONAVENTURE/AFP via Getty Images)

AFP via Getty Images

Will employers accept AI-issued credentials on par with degrees? Could bias in the system reinforce inequalities? How will user data be protected? And will job seekers and employers be willing to adopt an entirely new platform? ChatGPT’s path to trust, adoption, and success depends not only on technology but on credibility. AI and education could help parents and children understand the path forward.

Still, the upside is significant. ChatGPT could recast AI from a job destroyer to a job enabler. Combining credentials, tutoring, and matching in one seamless experience may position OpenAI not just as LinkedIn’s competitor, but as the architect of a new category: the AI-driven opportunity engine.

The Future For Jobs MayBe ChatGPT

The traditional hiring playbook is outdated. Degrees are slow and often outdated, resumes are noisy, and job posts are overwhelming. Embedding seamless skills certification and learning into hiring may rewrite the hiring playbook. Will this help positively impact AI and Education?

If OpenAI succeeds, opportunities may shift from “where did you go to school?” to “what can you do?”

That paradigm shift could open doors for millions and help employers access untapped talent. We’re witnessing the early outlines of what may become one of the most significant AI applications of the next decade.

ChatGPT may not just challenge LinkedIn—it may fundamentally redefine how skills, work, and opportunity connect in a digital age.

Tools & Platforms

Harvard develops AI to identify life-changing gene-drug combinations

Early results suggest the system could speed drug discovery, reduce costs, and highlight entirely new therapeutic pathways for neurodegenerative and rare diseases.

Researchers at Harvard Medical School unveiled an AI designed to match genes and drugs to combat disease in cells. The system, called PDGrapher, aims to tackle conditions ranging from Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s to rare disorders like X-linked Dystonia-Parkinsonism.

Unlike traditional tools that only detect correlations, PDGrapher forecasts which gene-drug pairings can restore healthy cellular function and explains their mechanisms. It may speed up research, lower expenses, and point to novel treatments.

Early tests suggest that PDGrapher can identify known effective combinations and propose new ones that have yet to be validated. If validated in trials, the technology could move medicine towards personalised treatments.

The debut of PDGrapher reflects a broader trend of AI transforming biotechnology. Innovations in AI are accelerating research by mapping biological systems with unprecedented speed, showing how machine learning can decode complex biological systems faster than ever before.

Would you like to learn more about AI, tech and digital diplomacy? If so, ask our Diplo chatbot!

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms4 weeks ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy1 month ago

Ethics & Policy1 month agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi