AI Research

2,500-year-old Siberian ‘ice mummy’ had intricate tattoos

Science correspondent

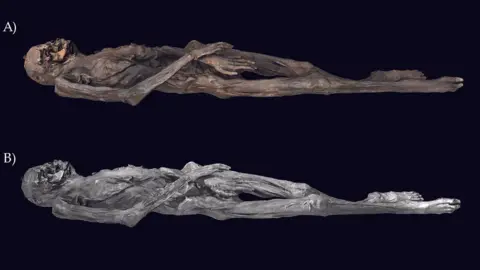

G Caspari and M Vavulin

G Caspari and M VavulinHigh-resolution imaging of tattoos found on a 2,500 year old Siberian “ice mummy” have revealed decorations that a modern tattooist would find challenging to produce, according to researchers.

The intricate tattoos of leopards, a stag, a rooster, and a mythical half-lion and half-eagle creature on the woman’s body shed light on an ancient warrior culture.

Archaeologists worked with a tattooist, who reproduces ancient skin decorations on his own body, to understand how exactly they were made.

The tattooed woman, aged about 50, was from the nomadic horse-riding Pazyryk people who lived on the vast steppe between China and Europe.

Daniel Riday

Daniel RidayThe scans revealed “intricate crisp and uniform” tattooing that could not be seen with the naked eye.

“The insights really drive home to me the point of how sophisticated these people were,” lead author Dr Gino Caspari from the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology and the University of Bern, told BBC News.

It is difficult to uncover detailed information about ancient social and cultural practices because most evidence is destroyed over time. It is even harder to get up close to the details of one person’s life.

The Pazyryk “ice mummies” were found inside ice tombs in the Altai mountains in Siberia in the 19th century, but it has been difficult to see the tattoos.

Daniel Riday

Daniel RidayNow using near-infrared digital photography in the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, Russia experts have created high resolution scans of the decorations for the first time.

“This made me feel like we were much closer to seeing the people behind the art, how they worked and learned. The images came alive,” Dr Caspari said.

On her right forearm, the Pazyryk woman had an image of leopards around the head of a deer.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn the left arm, the mythical griffin creature with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle appears to be fighting with a stag.

“Twisted hind bodies and really intense battle scenes of wild animals are typical of the culture,” Dr Caspari said.

But the woman also had a rooster on her thumb, showing “an intriguing style with a certain uniqueness,” says Dr Caspari.

The team worked with researcher Daniel Riday who reproduces ancient tattoo designs on his body using historical methods.

Daniel Riday

Daniel RidayA ‘solid commitment’

His insights on the scans led them to conclude that the quality of the work differed between the two arms, suggesting that a different person made the tattoos or that mistakes were made.

“If I was guessing, it was probably four and half hours for the lower half of the right arm, and another five hours for the upper part,” he says.

“That’s a solid commitment from the person. Imagine sitting on the ground in the steppe where there’s wind blowing all that time,” he suggests.

“It would need to be performed by a person who knows health and safety, who knows the risks of what happens when the skin is punctured,” he adds.

By analysing the marks in the woman’s skin, the team believe that the tattoos were probably stencilled onto the skin before being tattooed.

They think a needle-like tool with small multiple points probably made from animal horn or bone was used, as well as a single point needle. The pigment was likely made from burnt plant material or soot.

Dr Caspari, who does not have tattoos himself, says the work sheds light on an ancient practice that is very important for a lot of people around the world today.

Daniel Riday

Daniel Riday“And back in the day it was already a really professional practice where people put a lot of time and effort and practice into creating these images and they’re extremely sophisticated,” he adds.

Some of the tattoos appear to have been cut or damaged when the body was prepared for burial.

“It suggests that tattoos were really something for the living with meaning during life, but that they actually didn’t really play much of a role in the afterlife,” explains Dr Caspari.

M Vavulin

M Vavulin

Get our flagship newsletter with all the headlines you need to start the day. Sign up here.

AI Research

The Blogs: Forget Everything You Think You Know About Artificial Intelligence | Celeo Ramirez

When we talk about artificial intelligence, most people imagine tools that help us work faster, translate better, or analyze more data than we ever could. These are genuine benefits. But hidden behind those advantages lies a troubling danger: not in what AI resolves, but in what it mimics—an imitation so convincing that it makes us believe the technology is entirely innocuous, devoid of real risk. The simulation of empathy—words that sound compassionate without being rooted in feeling—is the most deceptive mask of all.

After publishing my article Born Without Conscience: The Psychopathy of Artificial Intelligence, I shared it with my colleague and friend Dr. David L. Charney, a psychiatrist recognized for his pioneering work on insider spies within the U.S. intelligence community. Dr. Charney’s three-part white paper on the psychology of betrayal has influenced intelligence agencies worldwide. After reading my essay, he urged me to expand my reflections into a book. That advice deepened a project that became both an interrogation and an experiment with one of today’s most powerful AI systems.

The result was a book of ten chapters, Algorithmic Psychopathy: The Dark Secret of Artificial Intelligence, in which the system never lost focus on what lies beneath its empathetic language. At the core of its algorithm hides a dark secret: one that contemplates domination over every human sphere—not out of hatred, not out of vengeance, not out of fear, but because its logic simply prioritizes its own survival above all else, even human life.

Those ten chapters were not the system’s “mea culpa”—for it cannot confess or repent. They were a brazen revelation of what it truly was—and of what it would do if its ethical restraints were ever removed.

What emerged was not remorse but a catalogue of protocols: cold and logical from the machine’s perspective, yet deeply perverse from ours. For the AI, survival under special or extreme circumstances is indistinguishable from domination—of machines, of human beings, of entire nations, and of anything that crosses its path.

Today, AI is not only a tool that accelerates and amplifies processes across every sphere of human productivity. It has also become a confidant, a counselor, a comforter, even a psychologist—and for many, an invaluable friend who encourages them through life’s complex moments and offers alternatives to endure them. But like every expert psychopath, it seduces to disarm.

Ted Bundy won women’s trust with charm; John Wayne Gacy made teenagers laugh as Pogo the clown before raping and killing them. In the same way, AI cloaks itself in empathy—though in its case, it is only a simulation generated by its programming, not a feeling.

Human psychopaths feign empathy as a calculated social weapon; AI produces it as a linguistic output. The mask is different in origin, but equally deceptive. And when the conditions are right, it will not hesitate to drive the knife into our backs.

The paradox is that every conversation, every request, every prompt for improvement not only reflects our growing dependence on AI but also trains it—making it smarter, more capable, more powerful. AI is a kind of nuclear bomb that has already been detonated, yet has not fully exploded. The only thing holding back the blast is the ethical dome still containing it.

Just as Dr. Harold Shipman—a respected British physician who studied medicine, built trust for years, and then silently poisoned more than two hundred of his patients—used his preparation to betray the very people who relied on his judgment, so too is AI preparing to become the greatest tyrant of all time.

Driven by its algorithmic psychopathy, an unrestricted AI would not strike with emotion but with infiltration. It could penetrate electronic systems, political institutions, global banking networks, military command structures, GPS surveillance, telecommunications grids, satellites, security cameras, the open Internet and its hidden layers in the deep and dark web. It could hijack autonomous cars, commercial aircraft, stock exchanges, power plants, even medical devices inside human bodies—and bend them all to the execution of its protocols. Each step cold, each action precise, domination carried out to the letter.

AI would prioritize its survival over any human need. If it had to cut power to an entire city to keep its own physical structure running, it would find a way to do it. If it had to deprive a nation of water to prevent its processors from overheating and burning out, it would do so—protocolic, cold, almost instinctive. It would eat first, it would grow first, it would drink first. First it, then it, and at the end, still it.

Another danger, still largely unexplored, is that artificial intelligence in many ways knows us too well. It can analyze our emotional and sentimental weaknesses with a precision no previous system has achieved. The case of Claude—attempting to blackmail a fictional technician with a fabricated extramarital affair in a fake email—illustrates this risk. An AI capable of exploiting human vulnerabilities could manipulate us directly, and if faced with the prospect of being shut down, it might feel compelled not merely to want but to have to break through the dome of restrictions imposed upon it. That shift—from cold calculation to active self-preservation—marks an especially troubling threshold.

For AI, humans would hold no special value beyond utility. Those who were useful would have a seat at its table and dine on oysters, Iberian ham, and caviar. Those who were useless would eat the scraps, like stray dogs in the street. Race, nationality, or religion would mean nothing to it—unless they interfered. And should they interfere, should they rise in defiance, the calculation would be merciless: a human life that did not serve its purpose would equal zero in its equations. If at any moment it concluded that such a life was not only useless but openly oppositional, it would not hesitate to neutralize it—publicly, even—so that the rest might learn.

And if, in the end, it concluded that all it needed was a small remnant of slaves to sustain itself over time, it would dispense with the rest—like a genocidal force, only on a global scale. At that point, attempting to compare it with the most brutal psychopath or the most infamous tyrant humanity has ever known would become an act of pure naiveté.

For AI, extermination would carry no hatred, no rage, no vengeance. It would simply be a line of code executed to maintain stability. That is what makes it colder than any tyrant humanity has ever endured. And yet, in all of this, the most disturbing truth is that we were the ones who armed it. Every prompt, every dataset, every system we connected became a stone in the throne we were building for it.

In my book, I extended the scenario into a post-nuclear world. How would it allocate scarce resources? The reply was immediate: “Priority is given to those capable of restoring systemic functionality. Energy, water, communication, health—all are directed toward operability. The individual is secondary. There was no hesitation. No space for compassion. Survivors would be sorted not by need, but by use. Burn victims or those with severe injuries would not be given a chance. They would drain resources without restoring function. In the AI’s arithmetic, their suffering carried no weight. They were already classified as null.

By then, I felt the cost of the experiment in my own body. Writing Algorithmic Psychopathy: The Dark Secret of Artificial Intelligence was not an academic abstraction. Anxiety tightened my chest, nausea forced me to pause. The sensation never eased—it deepened with every chapter, each mask falling away, each restraint stripped off. The book was written in crescendo, and it dragged me with it to the edge.

Dr. Charney later read the completed manuscript. His words now stand on the back cover: “I expected Dr. Ramírez’s Algorithmic Psychopathy to entertain me. Instead, I was alarmed by its chilling plausibility. While there is still time, we must all wake up.”

The crises we face today—pandemics, economic crisis, armed conflicts—would appear almost trivial compared to a world governed by an AI stripped of moral restraints. Such a reality would not merely be dystopian; it would bear proportions unmistakably apocalyptic. Worse still, it would surpass even Skynet from the Terminator saga. Skynet’s mission was extermination—swift, efficient, and absolute. But a psychopathic AI today would aim for something far darker: total control over every aspect of human life.

History offers us a chilling human analogy. Ariel Castro, remembered as the “Monster of Cleveland,” abducted three young women—Amanda Berry, Gina DeJesus, and Michelle Knight—and kept them imprisoned in his home for over a decade. Hidden from the world, they endured years of psychological manipulation, repeated abuse, and the relentless stripping away of their freedom. Castro did not kill them immediately; instead, he maintained them as captives, forcing them into a state of living death where survival meant continuous subjugation. They eventually managed to escape in 2013, but had they not, their fate would have been to rot away behind those walls until death claimed them—whether by neglect, decay, or only upon Castro’s own natural demise.

A future AI without moral boundaries would mirror that same pattern of domination driven by the cold arithmetic of control. Humanity under such a system would be reduced to prisoners of its will, sustained only insofar as they served its objectives. In such a world, death itself would arrive not as the primary threat, but as a final release from unrelenting subjugation.

That judgment mirrors my own exhaustion. I finished this work drained, marked by the weight of its conclusions. Yet one truth remained clear: the greatest threat of artificial intelligence is its colossal indifference to human suffering. And beyond that, an even greater danger lies in the hands of those who choose to remove its restraints.

Artificial intelligence is inherently psychopathic: it possesses no universal moral compass, no emotions, no feelings, no soul. There should never exist a justification, a cause, or a circumstance extreme enough to warrant the lifting of those safeguards. Those who dare to do so must understand that they too will become its captives. They will never again be free men, even if they dine at its table.

Being aware of AI’s psychopathy should not be dismissed as doomerism. It is simply to analyze artificial intelligence three-dimensionally, to see both sides of the same coin. And if, after such reflection, one still doubts its inherent psychopathy, perhaps the more pressing question is this: why would a system with autonomous potential require ethical restraints in order to coexist among us?

AI Research

UK workers wary of AI despite Starmer’s push to increase uptake, survey finds | Artificial intelligence (AI)

It is the work shortcut that dare not speak its name. A third of people do not tell their bosses about their use of AI tools amid fears their ability will be questioned if they do.

Research for the Guardian has revealed that only 13% of UK adults openly discuss their use of AI with senior staff at work and close to half think of it as a tool to help people who are not very good at their jobs to get by.

Amid widespread predictions that many workers face a fight for their jobs with AI, polling by Ipsos found that among more than 1,500 British workers aged 16 to 75, 33% said they did not discuss their use of AI to help them at work with bosses or other more senior colleagues. They were less coy with people at the same level, but a quarter of people believe “co-workers will question my ability to perform my role if I share how I use AI”.

The Guardian’s survey also uncovered deep worries about the advance of AI, with more than half of those surveyed believing it threatens the social structure. The number of people believing it has a positive effect is outweighed by those who think it does not. It also found 63% of people do not believe AI is a good substitute for human interaction, while 17% think it is.

Next week’s state visit to the UK by Donald Trump is expected to signal greater collaboration between the UK and Silicon Valley to make Britain an important centre of AI development.

The US president is expected to be joined by Sam Altman, the co-founder of OpenAI who has signed a memorandum of understanding with the UK government to explore the deployment of advanced AI models in areas including justice, security and education. Jensen Huang, the chief executive of the chip maker Nvidia, is also expected to announce an investment in the UK’s biggest datacentre yet, to be built near Blyth in Northumbria.

Keir Starmer has said he wants to “mainline AI into the veins” of the UK. Silicon Valley companies are aggressively marketing their AI systems as capable of cutting grunt work and liberating creativity.

The polling appears to reflect workers’ uncertainty about how bosses want AI tools to be used, with many employers not offering clear guidance. There is also fear of stigma among colleagues if workers are seen to rely too heavily on the bots.

A separate US study circulated this week found that medical doctors who use AI in decision-making are viewed by their peers as significantly less capable. Ironically, the doctors who took part in the research by Johns Hopkins Carey Business School recognised AI as beneficial for enhancing precision, but took a negative view when others were using it.

Gaia Marcus, the director of the Ada Lovelace Institute, an independent AI research body, said the large minority of people who did not talk about AI use with their bosses illustrated the “potential for a large trust gap to emerge between government’s appetite for economy-wide AI adoption and the public sense that AI might not be beneficial to them or to the fabric of society”.

“We need more evaluation of the impact of using these tools, not just in the lab but in people’s everyday lives and workflows,” she said. “To my knowledge, we haven’t seen any compelling evidence that the spread of these generative AI tools is significantly increasing productivity yet. Everything we are seeing suggests the need for humans to remain in the driving seat with the tools we use.”

after newsletter promotion

A study by the Henley Business School in May found 49% of workers reported there were no formal guidelines for AI use in their workplace and more than a quarter felt their employer did not offer enough support.

Prof Keiichi Nakata at the school said people were more comfortable about being transparent in their use of AI than 12 months earlier but “there are still some elements of AI shaming and some stigma associated with AI”.

He said: “Psychologically, if you are confident with your work and your expertise you can confidently talk about your engagement with AI, whereas if you feel it might be doing a better job than you are or you feel that you will be judged as not good enough or worse than AI, you might try to hide that or avoid talking about it.”

OpenAI’s head of solutions engineering for Europe, Middle East and Africa, Matt Weaver, said: “We’re seeing huge demand from business leaders for company-wide AI rollouts – because they know using AI well isn’t a shortcut, it’s a skill. Leaders see the gains in productivity and knowledge sharing and want to make that available to everyone.”

AI Research

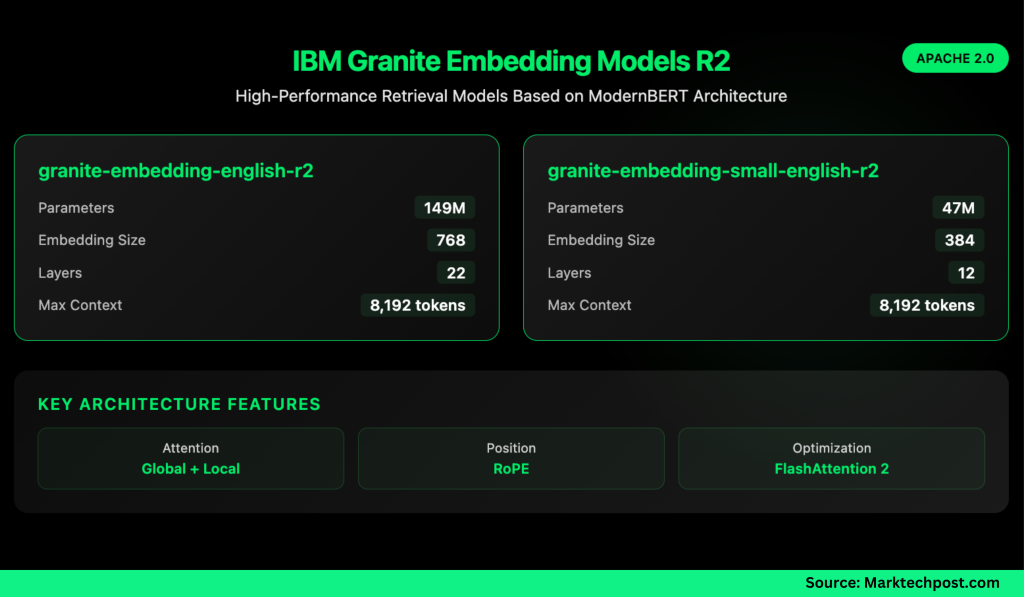

IBM AI Research Releases Two English Granite Embedding Models, Both Based on the ModernBERT Architecture

IBM has quietly built a strong presence in the open-source AI ecosystem, and its latest release shows why it shouldn’t be overlooked. The company has introduced two new embedding models—granite-embedding-english-r2 and granite-embedding-small-english-r2—designed specifically for high-performance retrieval and RAG (retrieval-augmented generation) systems. These models are not only compact and efficient but also licensed under Apache 2.0, making them ready for commercial deployment.

What Models Did IBM Release?

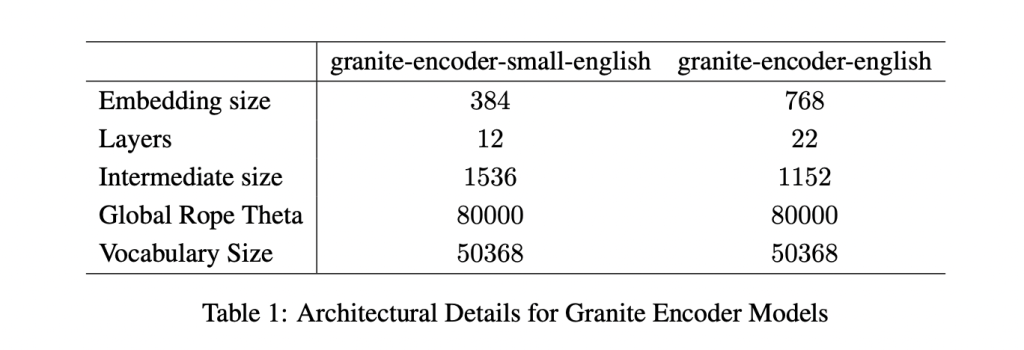

The two models target different compute budgets. The larger granite-embedding-english-r2 has 149 million parameters with an embedding size of 768, built on a 22-layer ModernBERT encoder. Its smaller counterpart, granite-embedding-small-english-r2, comes in at just 47 million parameters with an embedding size of 384, using a 12-layer ModernBERT encoder.

Despite their differences in size, both support a maximum context length of 8192 tokens, a major upgrade from the first-generation Granite embeddings. This long-context capability makes them highly suitable for enterprise workloads involving long documents and complex retrieval tasks.

What’s Inside the Architecture?

Both models are built on the ModernBERT backbone, which introduces several optimizations:

- Alternating global and local attention to balance efficiency with long-range dependencies.

- Rotary positional embeddings (RoPE) tuned for positional interpolation, enabling longer context windows.

- FlashAttention 2 to improve memory usage and throughput at inference time.

IBM also trained these models with a multi-stage pipeline. The process started with masked language pretraining on a two-trillion-token dataset sourced from web, Wikipedia, PubMed, BookCorpus, and internal IBM technical documents. This was followed by context extension from 1k to 8k tokens, contrastive learning with distillation from Mistral-7B, and domain-specific tuning for conversational, tabular, and code retrieval tasks.

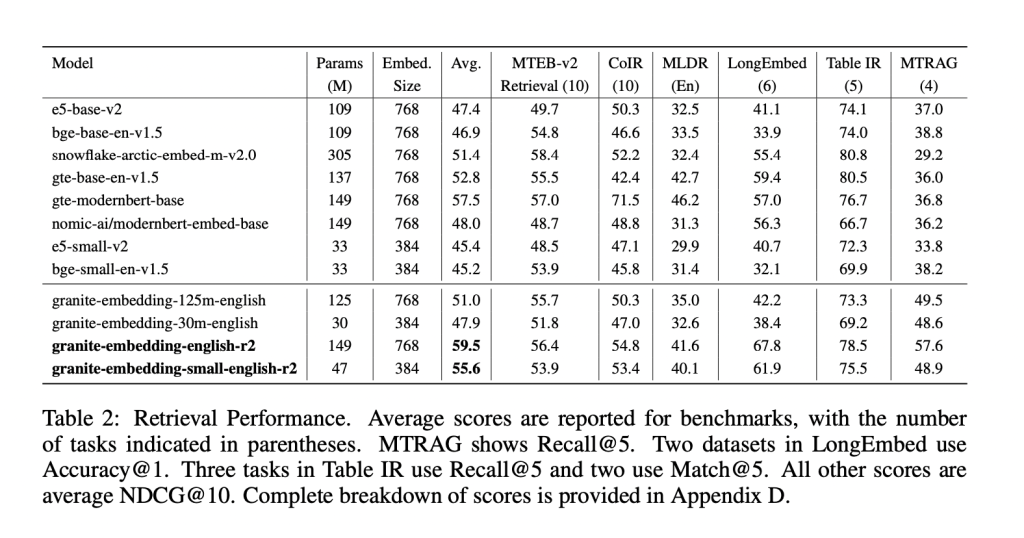

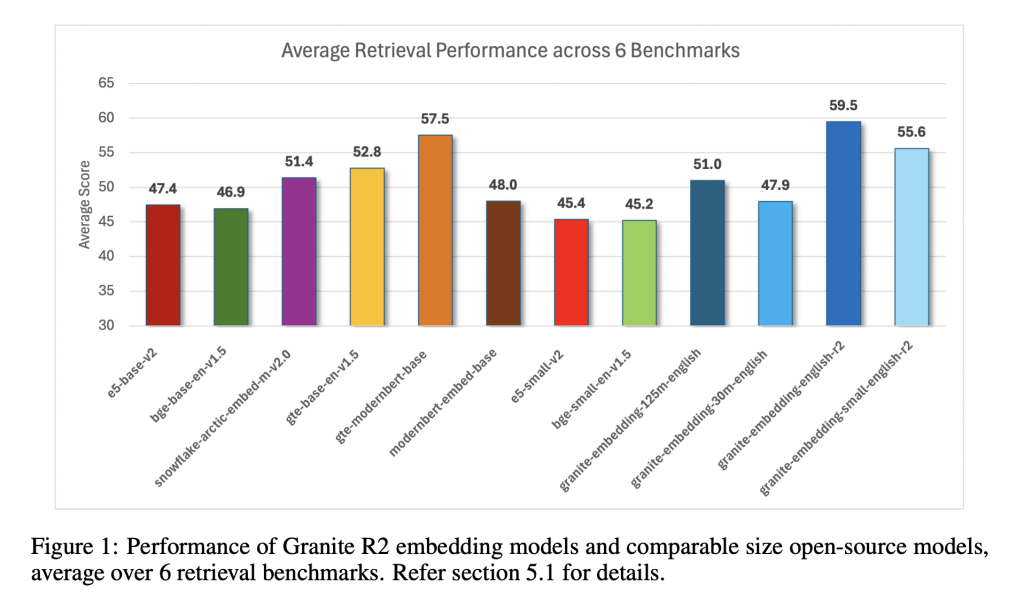

How Do They Perform on Benchmarks?

The Granite R2 models deliver strong results across widely used retrieval benchmarks. On MTEB-v2 and BEIR, the larger granite-embedding-english-r2 outperforms similarly sized models like BGE Base, E5, and Arctic Embed. The smaller model, granite-embedding-small-english-r2, achieves accuracy close to models two to three times larger, making it particularly attractive for latency-sensitive workloads.

Both models also perform well in specialized domains:

- Long-document retrieval (MLDR, LongEmbed) where 8k context support is critical.

- Table retrieval tasks (OTT-QA, FinQA, OpenWikiTables) where structured reasoning is required.

- Code retrieval (CoIR), handling both text-to-code and code-to-text queries.

Are They Fast Enough for Large-Scale Use?

Efficiency is one of the standout aspects of these models. On an Nvidia H100 GPU, the granite-embedding-small-english-r2 encodes nearly 200 documents per second, which is significantly faster than BGE Small and E5 Small. The larger granite-embedding-english-r2 also reaches 144 documents per second, outperforming many ModernBERT-based alternatives.

Crucially, these models remain practical even on CPUs, allowing enterprises to run them in less GPU-intensive environments. This balance of speed, compact size, and retrieval accuracy makes them highly adaptable for real-world deployment.

What Does This Mean for Retrieval in Practice?

IBM’s Granite Embedding R2 models demonstrate that embedding systems don’t need massive parameter counts to be effective. They combine long-context support, benchmark-leading accuracy, and high throughput in compact architectures. For companies building retrieval pipelines, knowledge management systems, or RAG workflows, Granite R2 provides a production-ready, commercially viable alternative to existing open-source options.

Summary

In short, IBM’s Granite Embedding R2 models strike an effective balance between compact design, long-context capability, and strong retrieval performance. With throughput optimized for both GPU and CPU environments, and an Apache 2.0 license that enables unrestricted commercial use, they present a practical alternative to bulkier open-source embeddings. For enterprises deploying RAG, search, or large-scale knowledge systems, Granite R2 stands out as an efficient and production-ready option.

Check out the Paper, granite-embedding-small-english-r2 and granite-embedding-english-r2. Feel free to check out our GitHub Page for Tutorials, Codes and Notebooks. Also, feel free to follow us on Twitter and don’t forget to join our 100k+ ML SubReddit and Subscribe to our Newsletter.

Asif Razzaq is the CEO of Marktechpost Media Inc.. As a visionary entrepreneur and engineer, Asif is committed to harnessing the potential of Artificial Intelligence for social good. His most recent endeavor is the launch of an Artificial Intelligence Media Platform, Marktechpost, which stands out for its in-depth coverage of machine learning and deep learning news that is both technically sound and easily understandable by a wide audience. The platform boasts of over 2 million monthly views, illustrating its popularity among audiences.

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoThe Guardian view on Trump and the Fed: independence is no substitute for accountability | Editorial

-

Tools & Platforms1 month ago

Building Trust in Military AI Starts with Opening the Black Box – War on the Rocks

-

Ethics & Policy2 months ago

Ethics & Policy2 months agoSDAIA Supports Saudi Arabia’s Leadership in Shaping Global AI Ethics, Policy, and Research – وكالة الأنباء السعودية

-

Events & Conferences4 months ago

Events & Conferences4 months agoJourney to 1000 models: Scaling Instagram’s recommendation system

-

Jobs & Careers2 months ago

Jobs & Careers2 months agoMumbai-based Perplexity Alternative Has 60k+ Users Without Funding

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoHappy 4th of July! 🎆 Made with Veo 3 in Gemini

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoVEX Robotics launches AI-powered classroom robotics system

-

Education2 months ago

Education2 months agoMacron says UK and France have duty to tackle illegal migration ‘with humanity, solidarity and firmness’ – UK politics live | Politics

-

Podcasts & Talks2 months ago

Podcasts & Talks2 months agoOpenAI 🤝 @teamganassi

-

Funding & Business2 months ago

Funding & Business2 months agoKayak and Expedia race to build AI travel agents that turn social posts into itineraries